While the Beatles were singing “She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah” in England, continental Europe was forming its own musical phenomenon. The French called it Yé-Yé, literally derived from the “yeah! yeah!” lyrics that had become the sound of British and American rock and roll. Inspired by the Anglophone craze, the Yé-Yé movement provided a French sensibility to the beat music of the 1960s, with its own French-language artists including Françoise Hardy, France Gall, and Sylvie Vartan. But Yé-Yé music didn’t just ‘translate’ rock and roll for the European market – it also expanded the genre sonically, exploring genres ranging from baroque to jazz to chanson (the French style of lyric-driven music). And unlike the male-dominated British invasion, Yé-Yé allowed many female stars to shine, bringing their sound to global audiences.

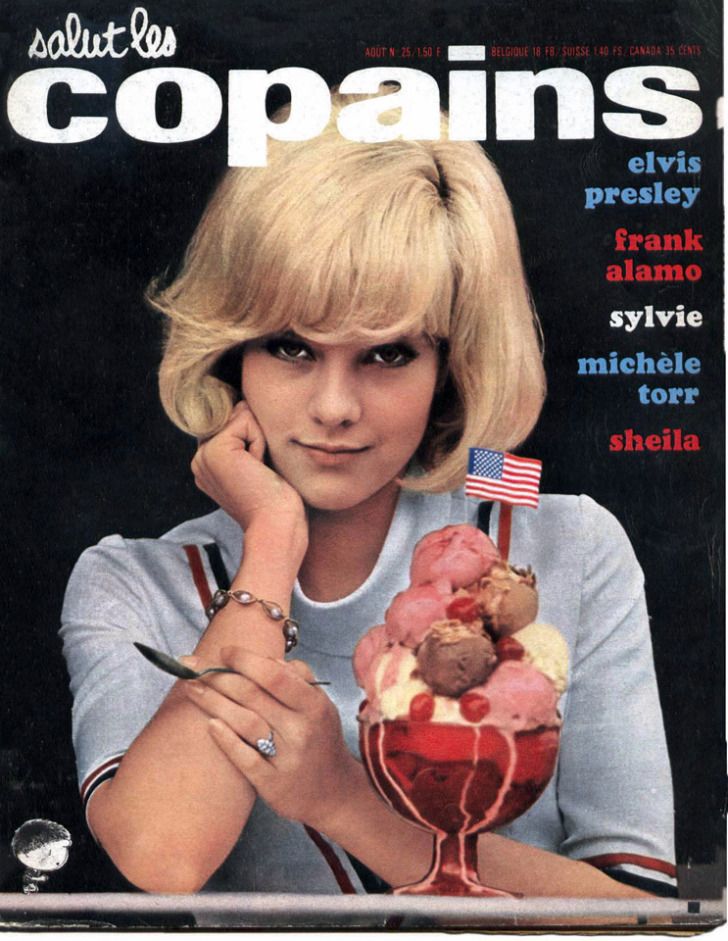

Some Yé-Yé girls got their start on the weekly radio program “Salut Les Copains” (think of it as the French equivalent of “Top of the Pops” or “American Bandstand”). Each show featured a weekly pop sweetheart. Yé-Yé music was ingrained in the quickly changing musical zeitgeist of the 1960s, pulling inspiration from Phil Spector’s “Wall of Sound” that was the backtrack for the era’s girl groups and the Beach Boys as well as the hit-making machine of New York City’s Brill Building. While many of these British and American musicians pushed the rapidly shifting gender boundaries in an era of bourgeoning sexual liberation, they had nothing on their more open, or promiscuous, French counterparts. There was a divide, however, between the largely male composers who wrote Yé-Yé music (most notably Jean Bouchéty, Michel Colombier and Serge Gainsbourg) and the young women who sang it.

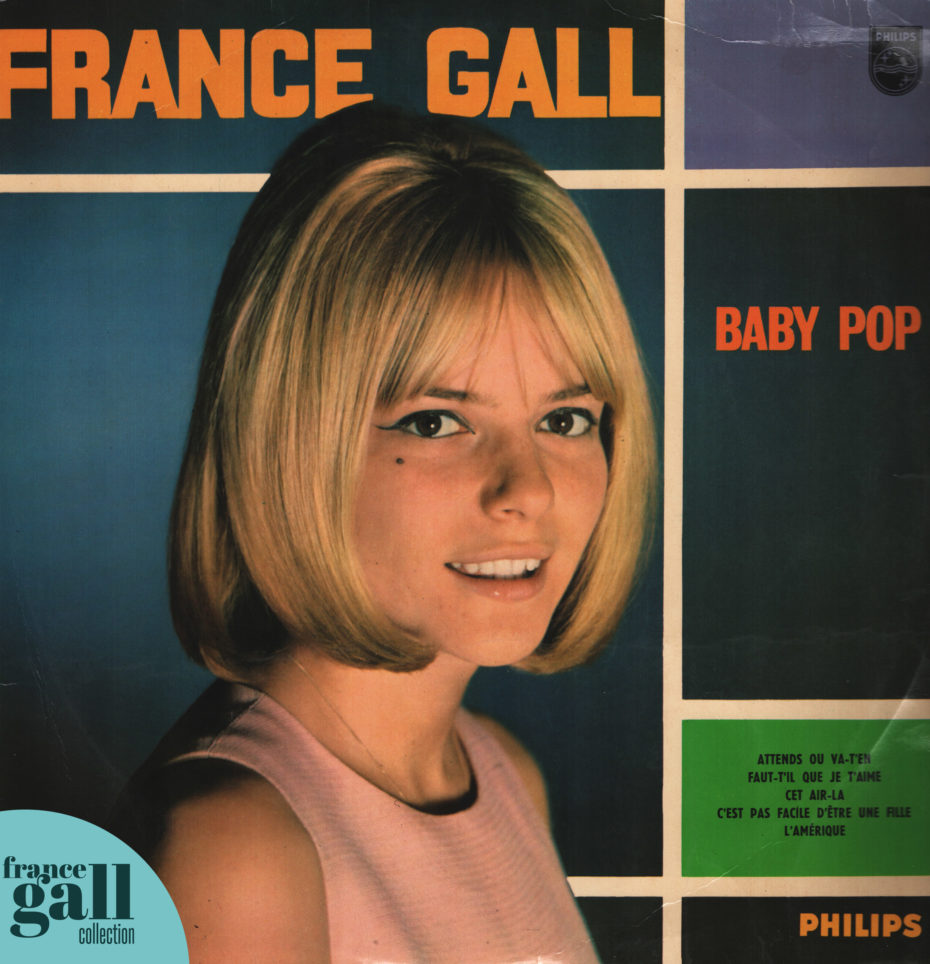

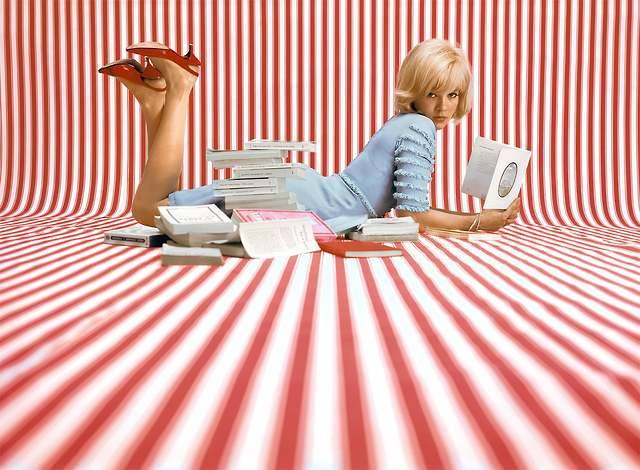

Take France Gall, the daughter of a lyricist who wrote songs for Edith Piaf. At 17, Gall won the Eurovision Song Contest for Luxembourg with a song written by Gainsbourg and a year later, became known for performing another one of his compositions, “Les Sucettes” (“The Lollipops”). The seemingly innocent song carries undertones about oral sex and Gall later said she was humiliated and felt taken advantage of. But as journalist Véronique Hyland points out, even feminist Simone de Beauvoir gave credit to the Lolita attitude of the Yé-Yé girl, recognising that she was “a carefree, in-between woman who giggled at the idea of marriage and commitment, in what was still a very conservative society”.

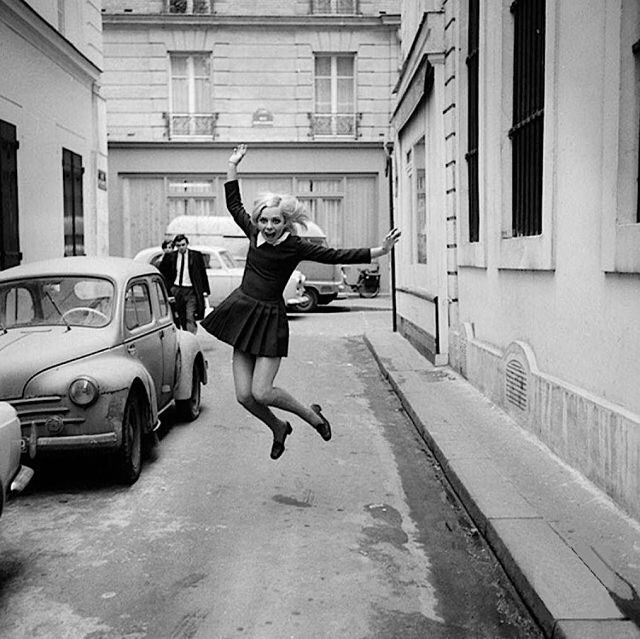

Jean-Emmanuel Deluxe, author of the great resource Ye-Ye Girls of ’60s French Pop, wrote that each Yé-Yé girl represented a unique archetype, like the fashionista, the nerd, the romantic and the protestor. But all of them embodied an enviable image of the 1960s Parisienne, effortlessly cool and stylish, whose look was envied and endlessly copied (but rarely successfully). Soon enough, the Brits wanted a piece of the pie of Yé-Yé culture.

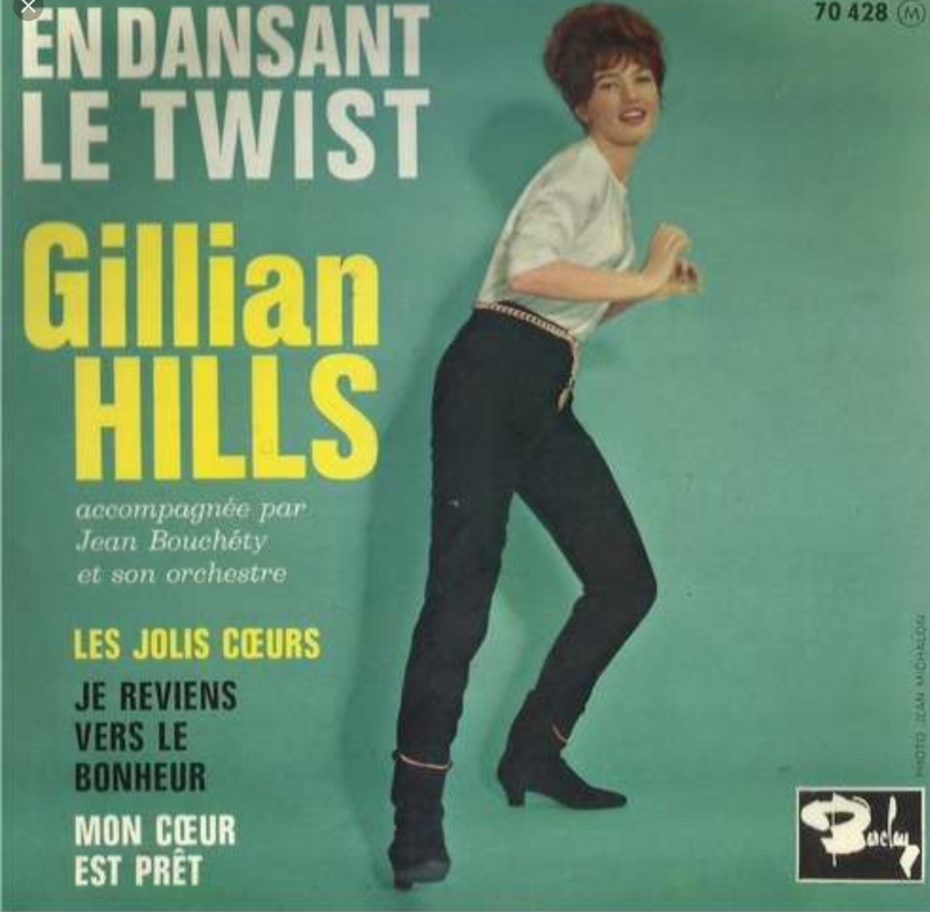

Adopted Parisiennes like Gillian Hills, who was tapped as the next Bardot, had several hits including “Zou Bisou Bisou,” “Ma Première Cigarette” and “Tut Tut Tut Tut”, as well as “Une Petite Tasse D’anxiété”, written by Serge Gainsbourg and sang together as his first Yé-Yé duet. Of course Hills wasn’t Yé-Yé’s only British infiltrators, the most famous being Jane Birkin. Originally gaining acclaim as an actress, Birkin met Gainsbourg on the set of the 1969 film Slogan in which they both starred. Their 1969 duet “Je T’aime,…Moi Non Plus” proved scandalous because of the sexually explicit lyrics, but was still a major hit in many countries. The song was first offered to fellow actress and part-time Yé-Yé singer Brigitte Bardot.

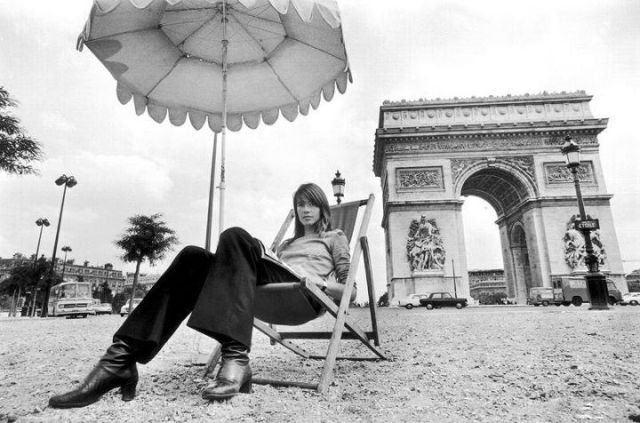

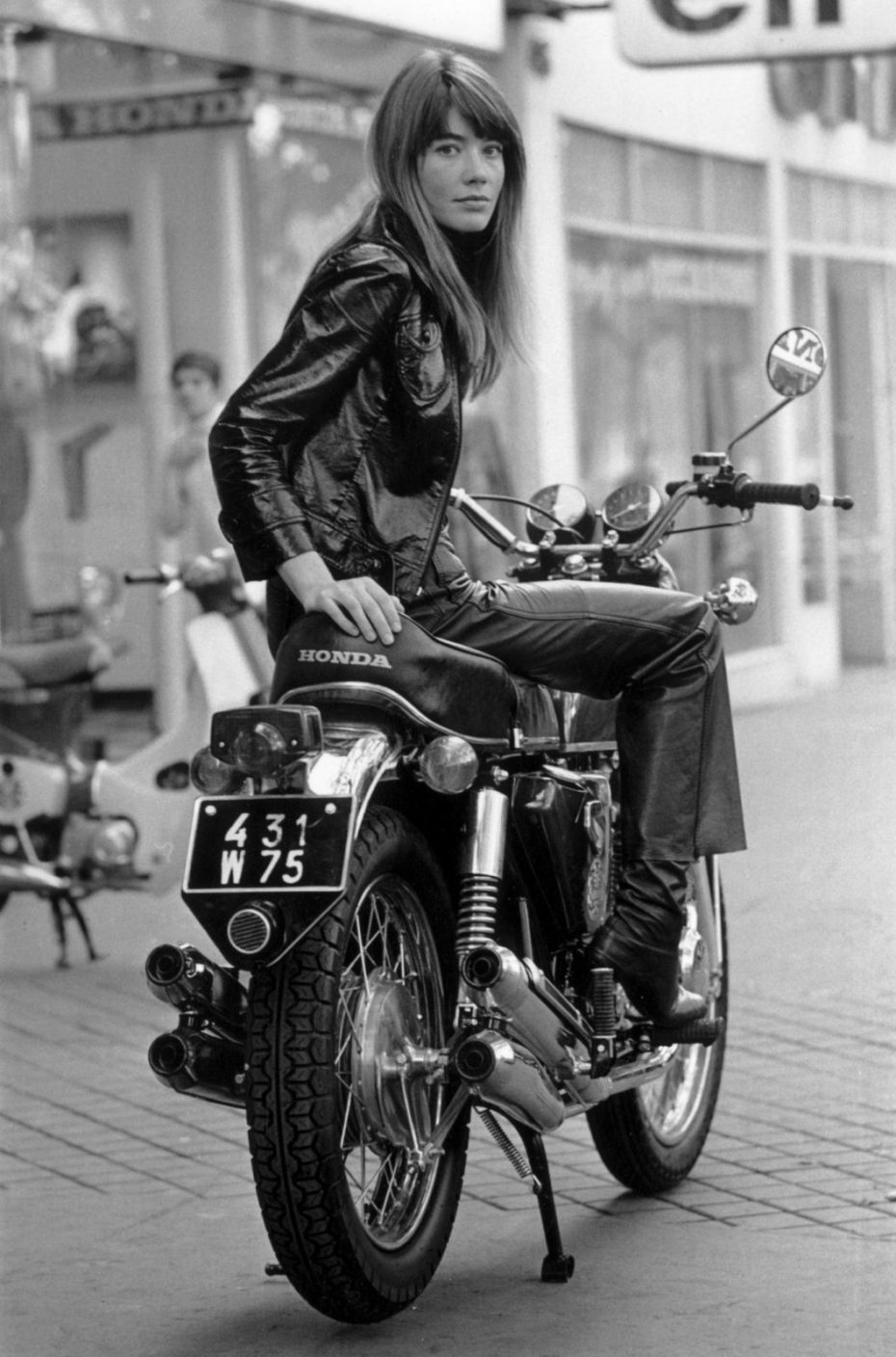

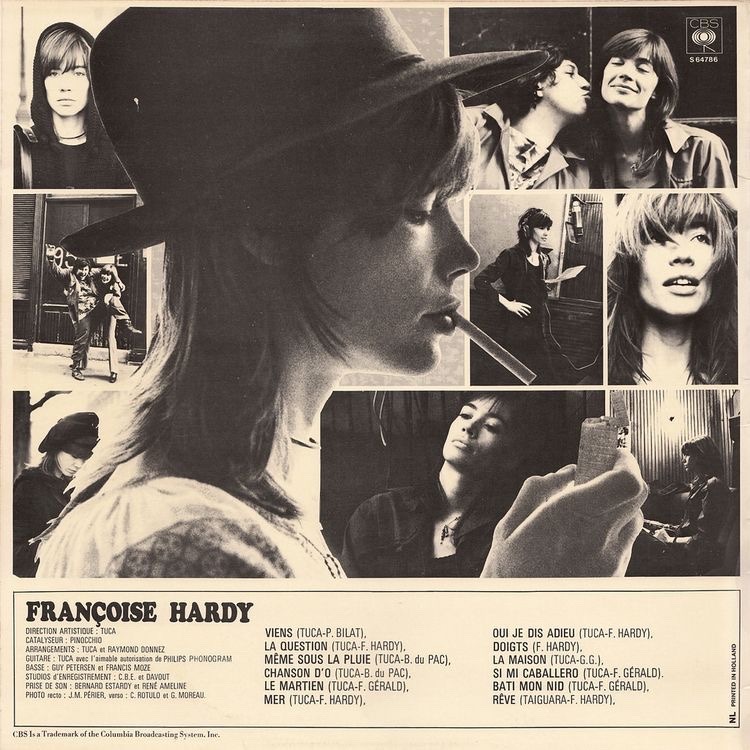

Unlike some one-hit wonders, Birkin and many other Yé-Yé artists were able to establish lifelong careers. One of the other most famous is undoubtedly Françoise Hardy, who might be the most melancholy and moody of the Yé-Yé movement. Growing up in a strict family, Hardy found freedom in Elvis Presley and other English-language rock music. In 1960, Françoise started auditioning for record labels, and was signed up by Vogue Records. Two years later she released the single “Tous les Garçons et les Filles”. It was a huge hit, selling two million copies – more than Edith Piaf had sold in eighteen years – and it catapulted her to the forefront of the music scene.

Notably, Hardy wrote or co-wrote much of her music and also became known for foregoing the en vogue miniskirts for menswear-inspired suits. With her striking girl-next-door beauty and androgynous sex appeal, Hardy remains a style icon to this day.

“The yé-yé girls’ youthful energy helped create a new, freer female archetype. And Hardy, with her love of suits, pushed the menswear-as-womenswear look as liberation”. The writer, singer and Left Bank intellectual became an inspiration for other artists like Bob Dylan and Mick Jagger. While Yé-Yé had found its roots essentially copying English rock & roll, Hardy seemed to re-position the French movement at the forefront of 1960s cool.

“She was the ultimate pin-up of most hip, Chelsea, beat bedroom walls, and I know for a fact that many of the groups who were notorious and slowly becoming successful, such as the Rolling Stones, Brian Jones and Mick Jagger, John Lennon, Paul McCartney and many others were desperately interested in having Françoise Hardy become their girlfriend in some way,” wrote Malcolm McLaren (manager of the Sex Pistols). David Bowie even admitted, “I was for a very long time passionately in love with her, as I’m sure she’s guessed.”

While last year, Hardy announced she would no longer be singing because of the impact of cancer therapy, she has also worked as an astrologer and published multiple fiction and nonfiction books.

Some Yé-Yé artists also expanded their performances beyond singing, like Sylvie Vartan who became known for her elaborate choreographed dancing that was popular on French and Italian television, well into the 1970s and beyond. The Armenian-Bulgarian Vartan married legendary French singer and actor Johnny Hallyday, who she toured and starred in movies with. Unlike some of her counterparts, Vartan released equally successful singles in both French and English, like “La Plus Belle Pour Aller Danser” (one of her early hits) and “I’m Watching You,” written by the Canadian Paul Anka. She has continued to entrance fans young and old, including releasing the 2010 album “Soleil Bleu” with a new generation of artists including Arthur H, Julien Doré and La Grande Sophie.

Despite their success and influence on both music and culture more broadly, Yé-Yé girls have sadly been dismissed because of the supposed shallow and youthful focus of their music. Of course, the men connected to Yé-Yé like Gainsbourg have never faced this criticism. Consequently, some ‘60s stars have been largely forgotten, like Nancy Holloway, one of the few Black and American Yé-Yé singers.

Holloway was originally from Ohio, but fell in love with Paris, which fell in love with her; her accent won her fans for her French versions of American hits, most notably “T’en Vas Pas Comme Ca,” a cover of Dionne Warwick’s “Don’t Make me Over.” She went from performing at the Moulin Rouge to owning her own Paris nightclub.

For many young women, Yé-Yé provided not only an opportunity to express themselves creatively, but also to find commercial success during an era when Second Wave feminism and France’s student protests were pushing for social equality. Yé-Yé songs might not have been as overtly political or revolutionary, but they found ways to assert their newfound independence, albeit often with jingly melodies and danceable beats. As Hardy sang on the 1966 track “Je changerais d’avis,”

“Life is not one boy

One face to love

Life is not one passion

Forever, lit.”