Corsets could be blamed (among many things) for preventing a lot of women throughout history from living their best lives, but Camille du Gast was not one of them. She was a self-styled “exploratrice” with a mind of her own and a penchant for speed. If you weren’t familiar with any women pursuing race car driving at the turn of the century, Camille was one of a small handful of pioneers. But she was also an all-round exceptional athlete and daredevil; a balloonist, a parachute jumper, motorboat racer, fencer, tobogganist, skier, rifle and pistol shot, equestrian — and occasionally, she liked to flex her artistic side as a concert pianist and singer. One might also say that Camille had nine lives, after emerging unscathed from an infamous “race of death” at the dawn of motorsports, having nearly drowned at sea in the pursuit of another trophy – oh, and casually surviving an assassination attempt ordered by her own daughter. Hers is a tale of scandal, betrayal, triumph and above all, velocity of every kind, all set against the high society glamour of la Belle Époque, France’s Gilded Age. Buckle up.

Born in Paris in 1868, Camille was already a part of wealthy bourgeoisie society when at 22 years-old, she married Jules Crespin, a well-to-do majority shareholder of one of the largest department stores in France. Only five years later however, he was dead, and his unexpected departure had left a young widowed mother to her own devices – albeit with a serious fortune and an insatiable sense of adventure.

Camille was no average lady of leisure. She had already been exploring elite new sports with her late husband, particularly hot air ballooning. In fact, she took a liking to parachuting out of them (which made great publicity stunts for the family business). She was fascinated to the point of obsession with all sorts of novel forms of motion and propulsion, most notably so with motor cars, which were still a luxurious curiosity at the time. Known as the most beautiful woman in Paris of her day, Camille proceeded to become an unlikely collector of automobiles and cruised around town in some of the very earliest of cars such as a Peugot and a Panhard et Levassor. She must have been quite the sight.

But with her husband gone, it was only a matter of time before such an established, adventurous, ambitious and envied woman would become the target of salacious society scandal. Throw in a bitter family feud over money and you’ve got a recipe for trouble.

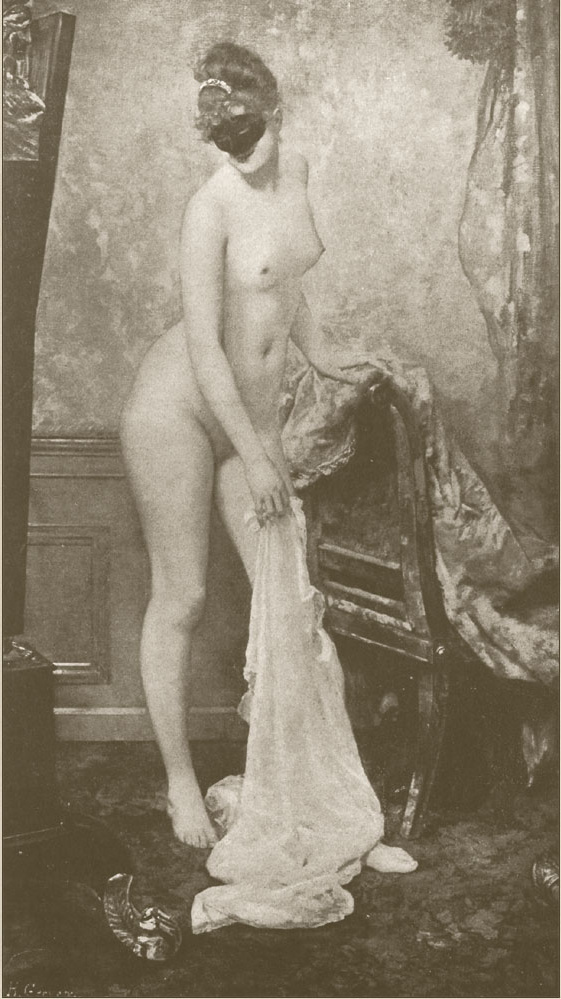

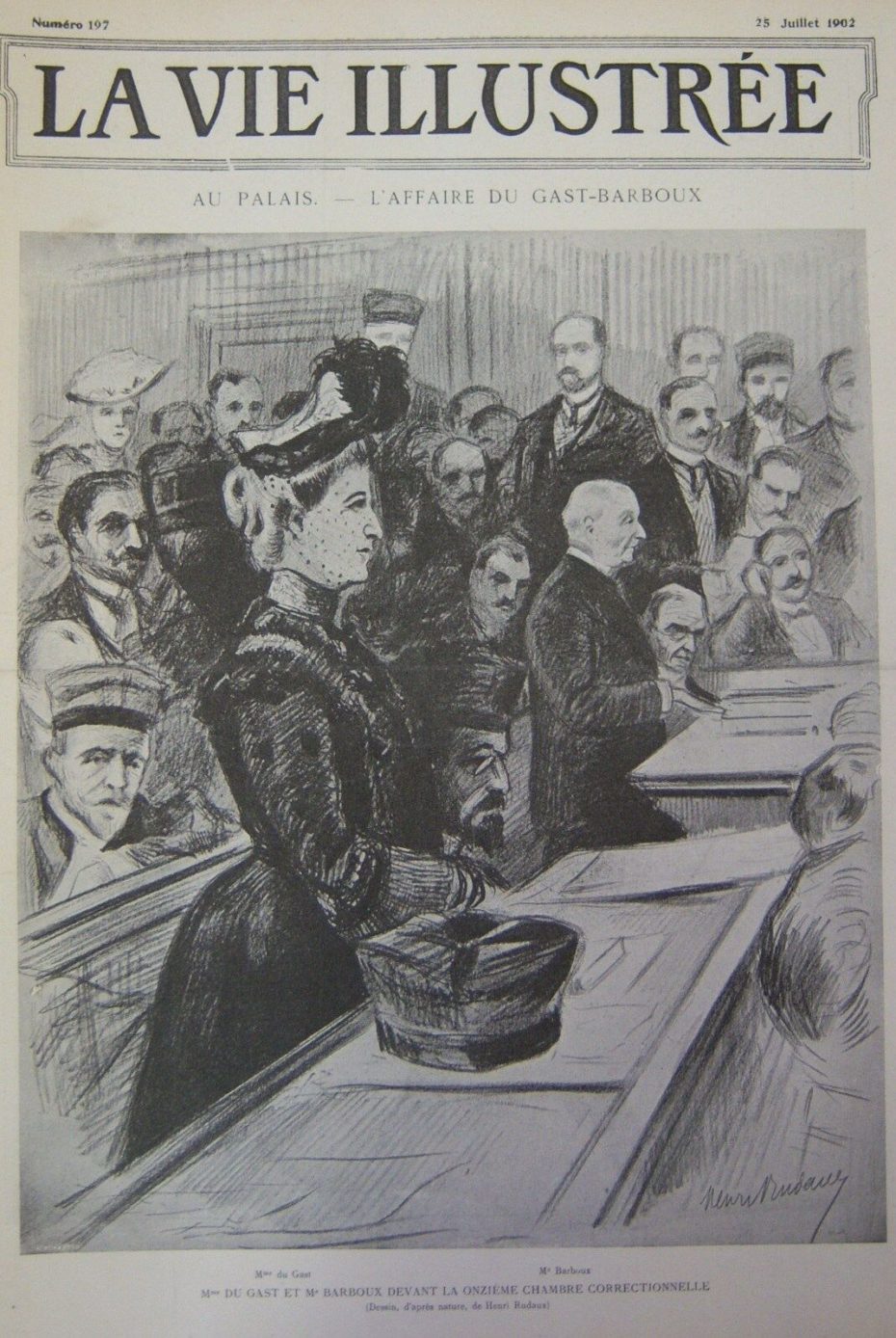

Back when Camille was a seventeen year-old debutante, the prolific Parisian Belle Époque artist Henri Gervex, painted La Femme au Masque, a nude portrait of a masked woman whose identity was never revealed. Exquisitely and realistically painted, it was a sensation from the start and had immediately attracted a fair bit of gossip and intrigue. Predictably women across ‘polite society’ were accused of being the sitter for the painting, but in 1902, Camille suddenly became the central figure in the Parisian scandal of La Femme au Masque.

It was at this moment that du Gast’s personal life took a turn for the worse. Let’s just say the Du Gast family dynamics weren’t great, and in the midst of bitter court battles involving Camille’s coming-of-age daughter and other relatives attempting to claim the family fortune, the mud-slinging got particularly nasty. In a seedy character assassination attempt, the family’s barrister formally and publicly accused Camille of posing for the La Femme au Masque painting, arguing that in the past, her late husband had duelled with the artist to defend her honour. Camille’s friends and even the painter Henri Gervex came to her defence, but the damage was done. Rumours spread like wildfire that it was in fact Camille in the notorious painting, creating a media circus, filling newspaper pages from as far afield as New York and Sydney. The reality was that the sitter was probably a known artist’s model of the day, Marie Renard, but the masked face in the picture actively invited a barrage of endless speculation and outrageous accusations. Camille managed to retain her fortune in the end, but by this time, she had lost interest in polite society and it was her all-encompassing love of sports and adventure that would take her on a path that she had previously and tentatively explored, but one that would dominate the rest of her life. She wanted to escape, and that’s exactly what she did from then onwards.

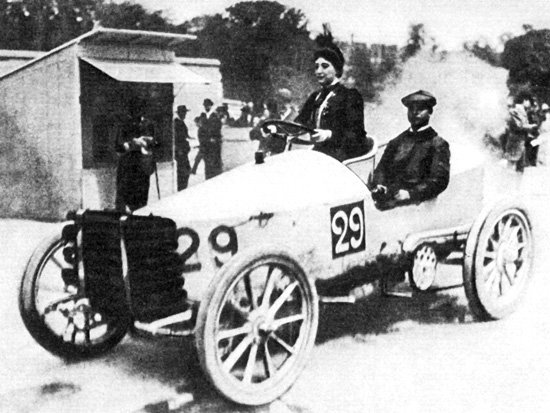

Camille was only the second woman in France to gain a driving license in 1897 but she would be the first woman to receive a speeding ticket in 1898 for travelling at 15km/h (rather than the legal 12km/h). From around 1900, after watching the first Gordon Bennett Cup, Camille du Gast became obsessed with racing the newest cars.

As part of a trio of wealthy female French motor celebrities (including Hélène de Rothschild, the first woman to ever have takn part in an international race) she entered countless competitions across Europe. Gordon Bennett, a fellow car enthusiast, media mogul, racing sponsor (and allegedly Camille’s lover), described her as “the greatest sportswoman of all time”, but the general consensus was that driving was too dangerous for women. In order to pilot the vehicles, Du Gast required a dangerously elevated upright seating design to accommodate the corsetry that the fashion of the time demanded. But when it came to avoiding accidents and driver safety, it was Camille that would ultimately come to the rescue of her male counterparts.

In the Paris to Madrid car race of 1903, one of her team’s drivers had overturned and she stopped to pull him out from under his rolled vehicle and nurse his injuries until help arrived. Two other drivers died during the race as did 6 or more spectators. In 1904, the Benz factory team offered Camille a car to race, but the French government introduced rules banning women drivers, despite her widely published protestations. Facing an outright ban on women racing motorcars after the 1903 Paris to Madrid “race of death”, Camille du Gast took to water. Boat racing had become the new vogue sport, and soon enough, she was piloting the Darracq, a slick low-profile auto boat down the river Seine.

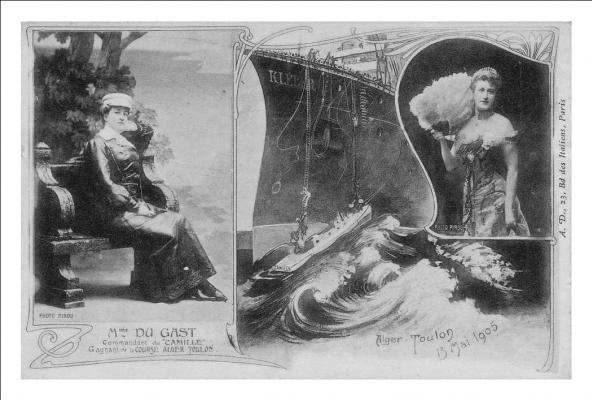

The press was terribly impressed with her nautical chic looks; her elegant hats, gloves, veil and full-length leather coats clinched by tight-fitting bustiers. She competed in the trans-Mediterranean race from Algiers to Toulon on a specially commissioned namesake auto boat, the Camille. During the second stage of the race, a severe storm sunk 6 of the seven competing boats, including Du Gast’s vessel, and she was pulled from the sea (unconscious) by a sailor on a nearby warship. Camille was still declared the winner of the race, having come closest to the finish before the storm.

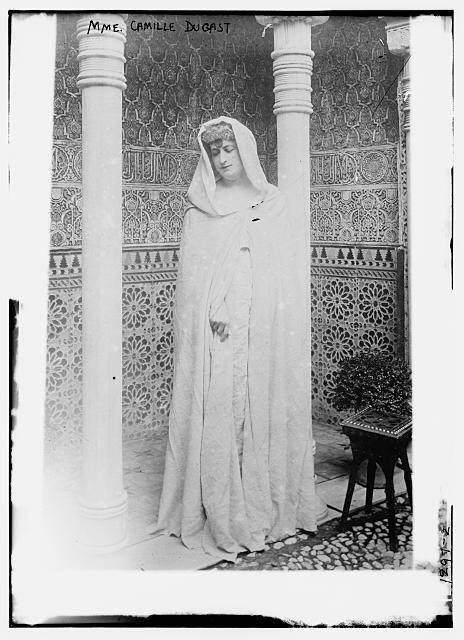

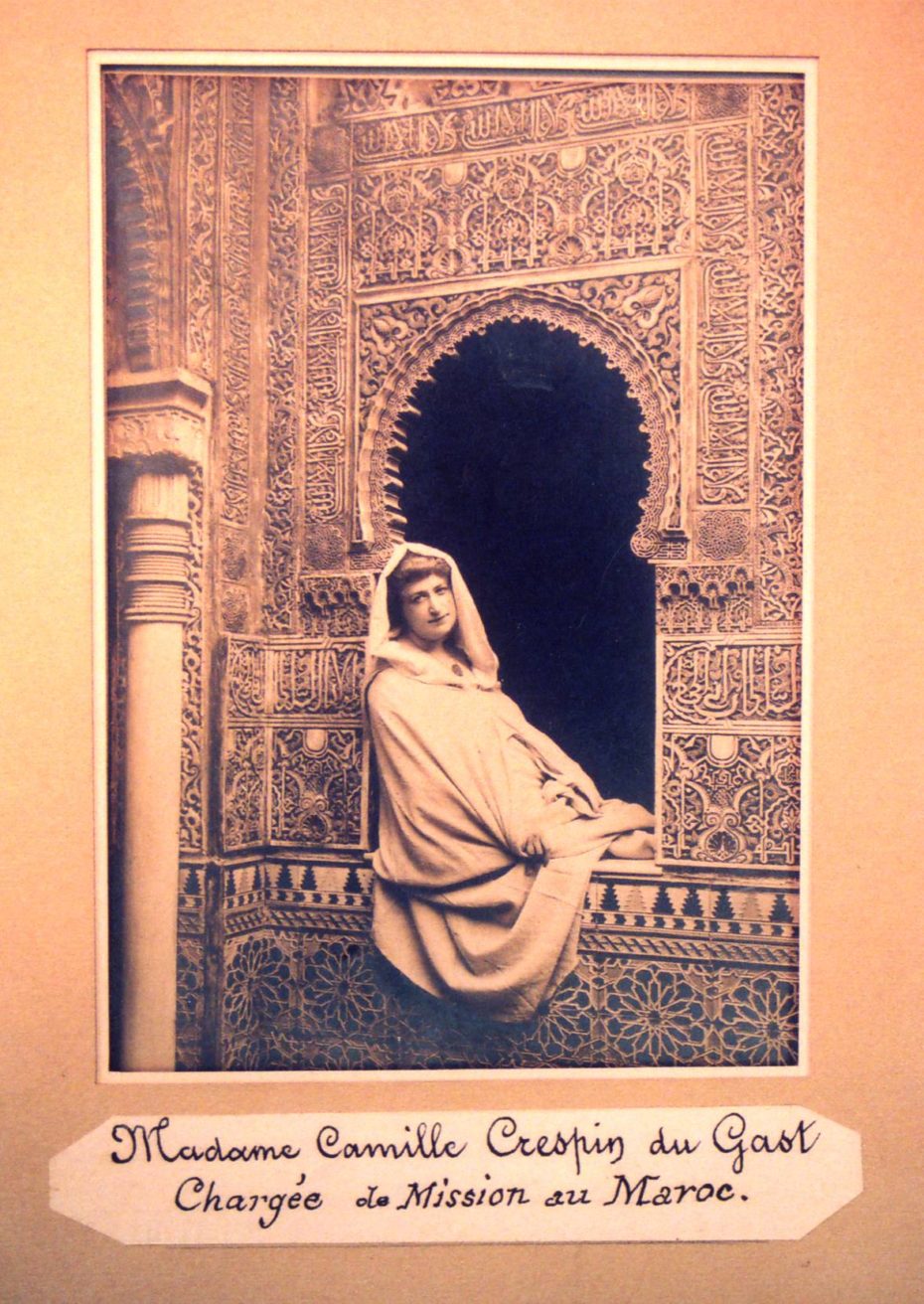

Curiously at this point she dipped her toes into world politics. In 1906 she attended the Algeciras Conference in Spain, where France and Germany had clashed over the future of Moroccan independence and being the celebrity that she was, she stepped in, hoping to help. The women’s journal La Vie heureuse reported that “It is not useless to hope that there, where the diplomats have not been able to succeed, the diplomacy of a woman might be able to”.

Inspired by her close involvement in the Moroccan crisis, she set out alone on horseback to explore the country. Later, in both 1910 and 1912, she was commissioned by the French government to return to Morocco, firstly on behalf of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and then on behalf of the Ministry of Agriculture where she was tasked to help local women distribute medicine. She noted after almost a year of travel she had improved the image of France and put this down to “a nice horse, a calm demeanour, authority and generosity”.

Camille du Gast had now been celebrated internationally for some years and she had achieved various sporting and political accolades. Her wealth and fame were still envied by her family, particularly by her own estranged and embittered daughter who, after numerous failed attempts to extort money from her mother, hired a gang of hitmen to Camille’s house in the middle of the night in 1910. Evidently, the assassins weren’t of the highest calibre, because when Camille was awoken by their presence, she confronted them and they immediately fled.

Something shifted for Camille in the wake of the ultimate betrayal at the hands of her only child. She turned to less adventurous, but still challenging pursuits, dedicating herself to the plight of animals and women. Camille served as president of the French Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and campaigned against bullfighting, leading protests of hundreds of demonstrators. She established centres for orphans and impoverished women and became vice-president of the leading women’s rights organisation in France. Whilst others would pioneer or lead in suffrage and politics, through Camille du Gast’s remarkable public profile and her ‘can-do’ culture in extreme and adventurous sports, she became an inspiration to many women. She continued to provide health-care to disadvantaged women and children in German-occupied Paris, until her death in 1942.

Camille is buried at the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, and it would seem, her incredible story was laid to rest with her. Known as ‘one of the richest and most accomplished widows in France’, she had the wealth, connections but most of all, the nerve to engage and explore activities where women’s participation was not encouraged the time. Where is her adventure storybook à la Jules Verne? Where is her place in the motorsports hall of fame? Heck, where is her Netflix period drama miniseries? Forget “Emily in Paris”, someone call Hollywood about the most fascinating woman of the Belle Epoque!