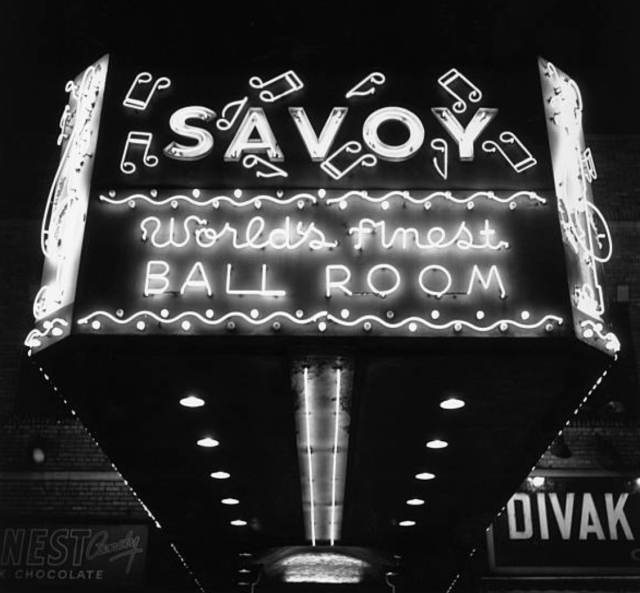

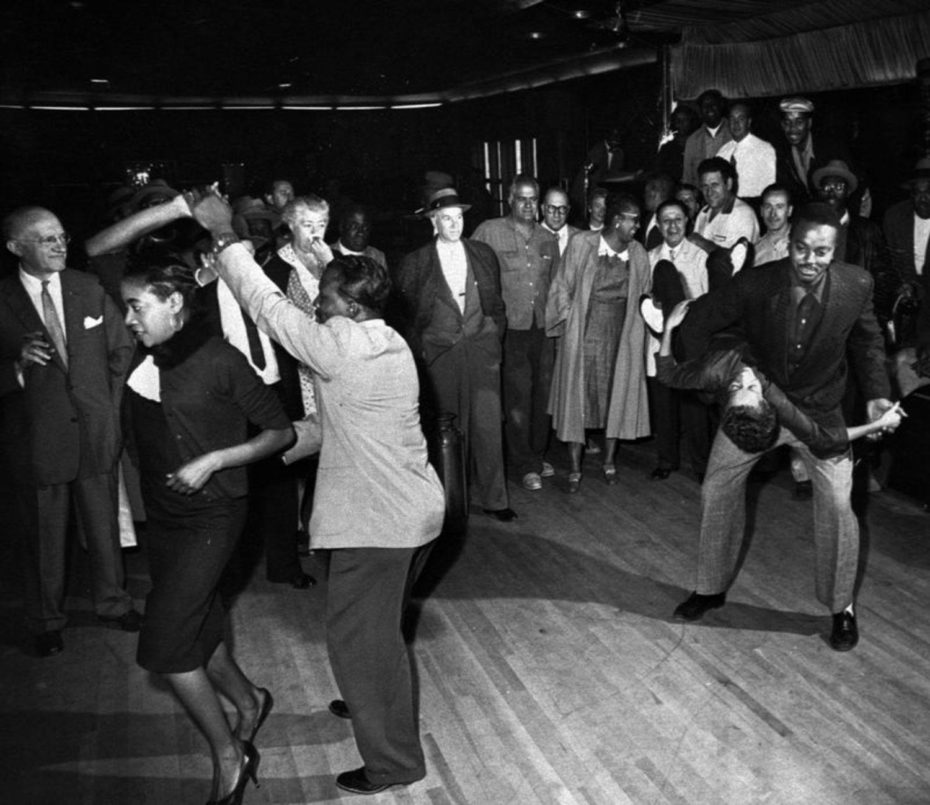

On West 140th Street and Lenox Avenue today, a drab supermarket squats in front of a housing project. It’s hard to believe that in the 1930s, the most famous dance club in the world stood on this dreary spot. Back then, the block was dominated by a two-story building with an enormous marquee sprinkled gaily with music notes that proclaimed “SAVOY World’s Finest Ballroom.” Up the stairs, high-flying Lindy Hop dancers competed to create ever-more jaw-dropping moves to the blistering sounds of the best big bands in America. What’s more, the Savoy Ballroom was the first dance club in America where Black and white people could freely dance together.

In the 1920s, New Yorkers had a plethora of choices to flail their arms and legs to the new jazz music that had taken the world by storm, but if you were a person of color, your options were far more limited. At the Roseland Ballroom, a rope was strung across part of the dance floor to keep Black people apart from white people. At the Cotton Club, the stage was all-Black but the audience was all-white. The only nightclub that was Black-owned and integrated was Small’s Paradise, but it was a sit-down spot with no room to dance.

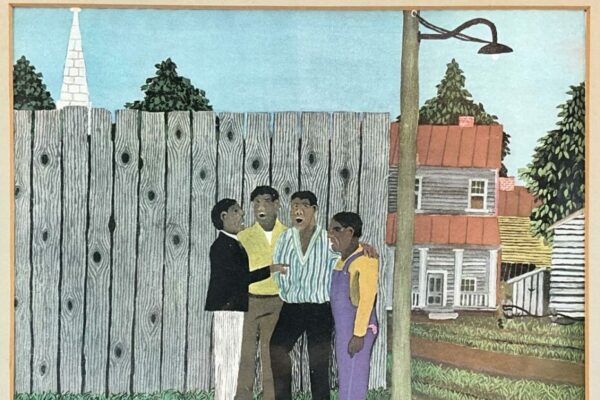

The Savoy Ballroom was established by Joe Faggen, part-owner of the Roseland Ballroom, and Jewish luggage manufacturer Moe Gale (née Moses Galewski). Shrewdly, the two white men hired Charles Buchanan to be their general manager. Born in Barbados, Buchanan had immigrated to Harlem at the age of six and was a pillar of the neighborhood. He was a successful real estate agent who was a friend of civil rights leader Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. and married Broadway star Bessie Allison, who would later become New York’s first Black Assemblywoman (pictured above).

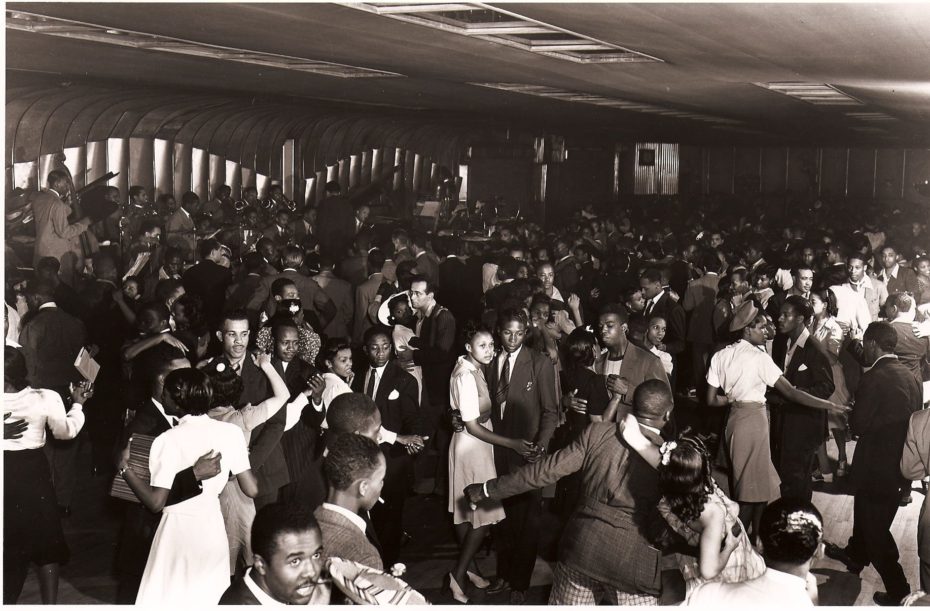

From the beginning, the Savoy Ballroom was envisioned as an opulent music hall where Black people would be welcome. Ticket prices were kept low so everyone could attend. Spanning the entire block, the Savoy had ornate French mirrors, luxurious carpeted lounges, and an enormous mahogany dance floor sparkling with colored lights.

There were two bandstands so the music could flow continuously from one band to next. “My first impression was that I had stepped into another world,” dancer Leon James recalled, “I had been to other ballrooms, but this was different – much bigger, more glamour, real class.” The Savoy opened on March 12, 1926 and was an instant success, turning away 2,000 people on its very first night.

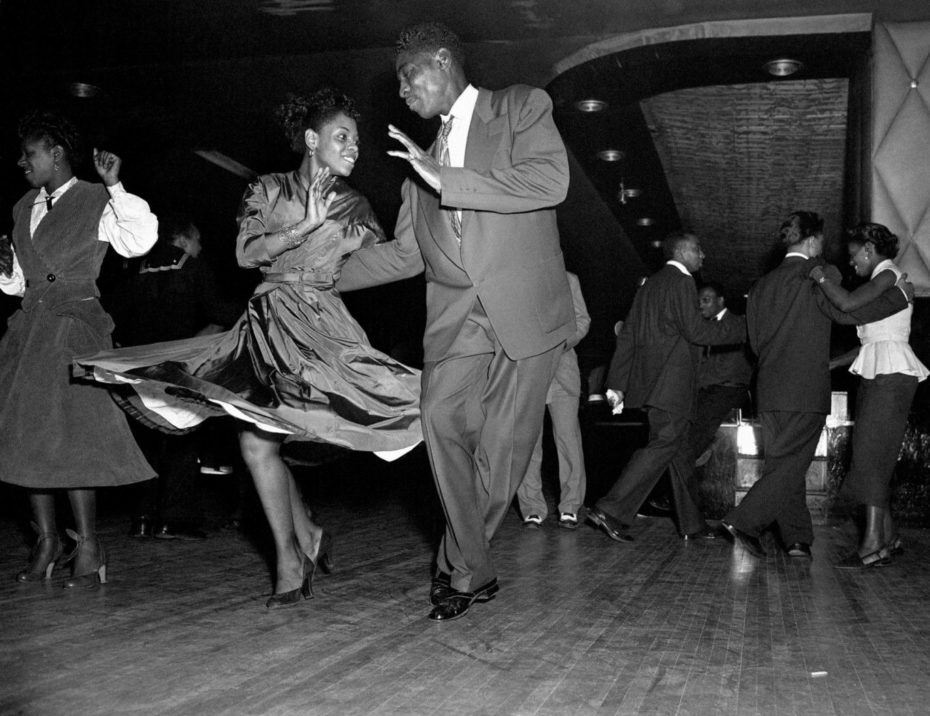

Being a leader in the community, Buchanan was sensitive to derogatory portrayals of Black people as “exotic” or “primitive” and saw the Savoy as a means towards racial uplift. He was uptight about the Charleston, deeming it uncouth, though it was too popular to avoid. He was serious about formal dress and no one could get in if they weren’t dressed to the nines. “Some folks have gotten the idea that the Savoy is too strict,” Buchanan stated in the Pittsburgh Courier, “They say that because we won’t stand for a lot of necking, indecent mooch dancing and the like that you can’t have a good time here. We want to tell you right now that’s a lot of applesauce.” Buchanan’s vision of a sedate and dignified ballroom was soon upended by a wild dance style sweeping the Harlem streets.

The origins of the Lindy Hop have been debated for decades but it’s safe to say that it emerged from the Charleston. The key difference in the Lindy Hop is a breakaway or swing out that allows each partner to improvise a few solo steps before coming back together.

The legend is that ‘Shorty’ George Snowden and Mattie Purnell first invented the breakaway at a dance marathon at the Manhattan Casino in the summer of 1928. The breakaway may have been out of sheer boredom after a week of dancing, or it may have been because Purnell lost her grip, forcing the two of them to improvise for a few beats. However it occurred, the spectators went wild, so Shorty George repeated the move. A reporter asked what they were doing and Shorty George responded, “I’m doing the hop! The Lindy Hop!” The swing out allowed for greater spontaneity and freedom of movement, instantly propelling social dance into a new direction. It spread like wild fire.

In tandem with the Lindy Hop, there was a shift in jazz music. A new generation of musicians were jiving to a back and forth rocking rhythm that was soon called “Swing”. To accentuate that swinging sensation, they arranged different sections of the band to call and respond to each other. There were also designated moments for solo riffs that echoed the Lindy Hop’s solo improvisations.

At the forefront of this new style of music was Chick Webb, a giant of jazz who stood 4 feet (1.2 metres) tall and suffered from severe curvature of the spine. Despite being in constant pain, Webb was a powerful drummer known for pyrotechnic riffs that propelled everyone out onto the dance floor. In 1931, the Chick Webb Band was engaged to play at the Savoy Ballroom and ended up at the helm of the house band for the next four years. With Webb perched on a specially made platform thundering away, the stage was set for a music and dance revolution.

The Savoy initially did not approve of the Lindy Hop. To evade the policing of his movements, Shorty George recalled weaving to the middle of a crowd before busting out his new moves. He even invented a traveling step to escape the ballroom’s tuxedoed bouncers when they headed his way. The dance continued to spread until it was too big to ignore. Eventually, Buchanan caught the drift and the Lindy Hop became part of the Savoy’s claim to fame. Shorty George was rewarded with a gilded lifetime pass to the ballroom.

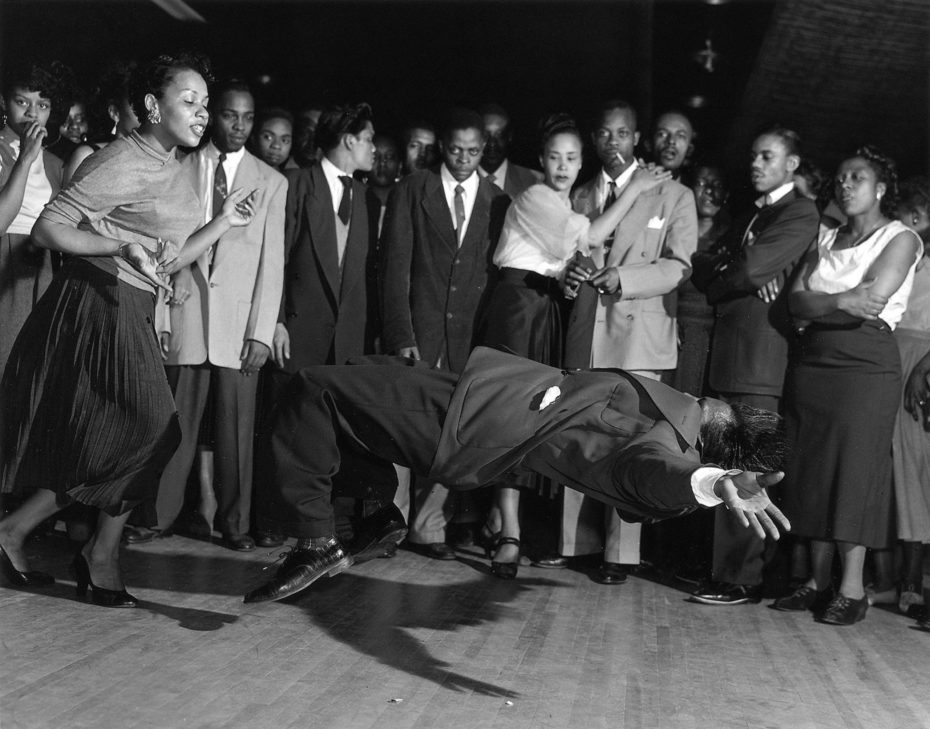

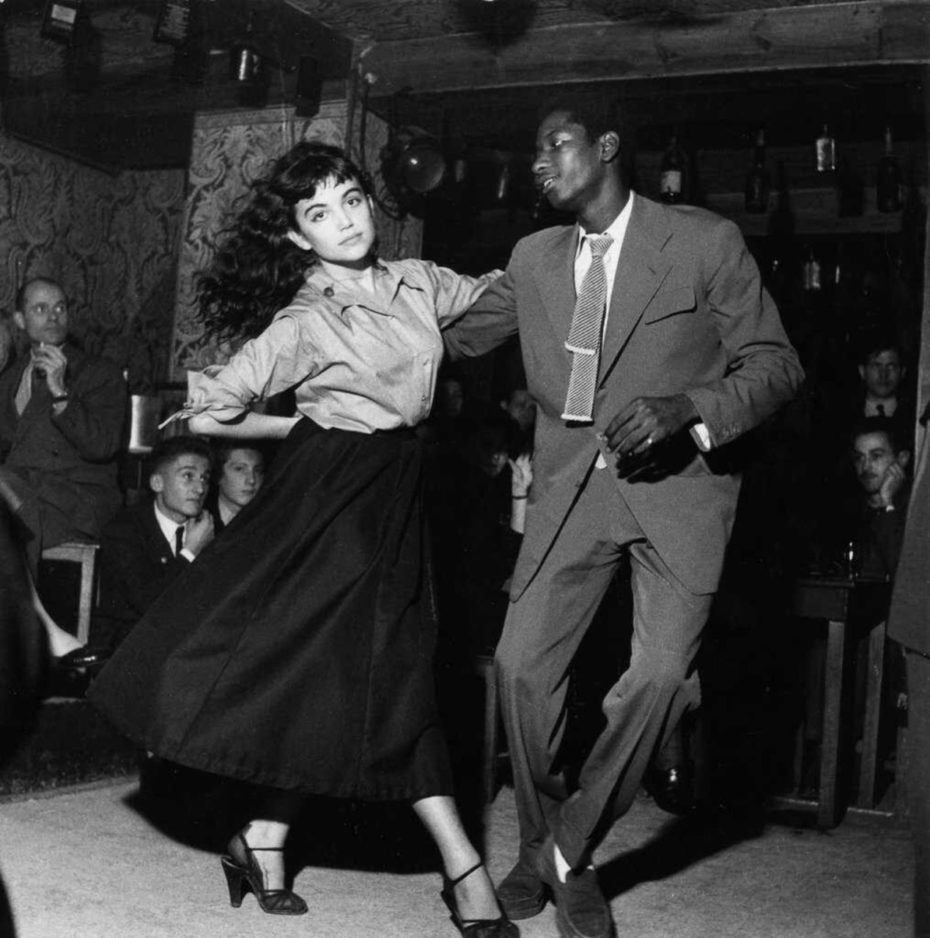

Dancer Mura Dehn remembers the shift, “In the mid-thirties the ballroom was invaded by youth. Gone, the evening gowns, the formal dress, the grown up sophistication. Jitterbugs made their debut. Thick-rimmed glasses, thick-soled sneakers, sport jackets, sweaters. Girls in bobby socks, flaring skirts, skull caps with a long feather. Ballroom bubbling with energy.”

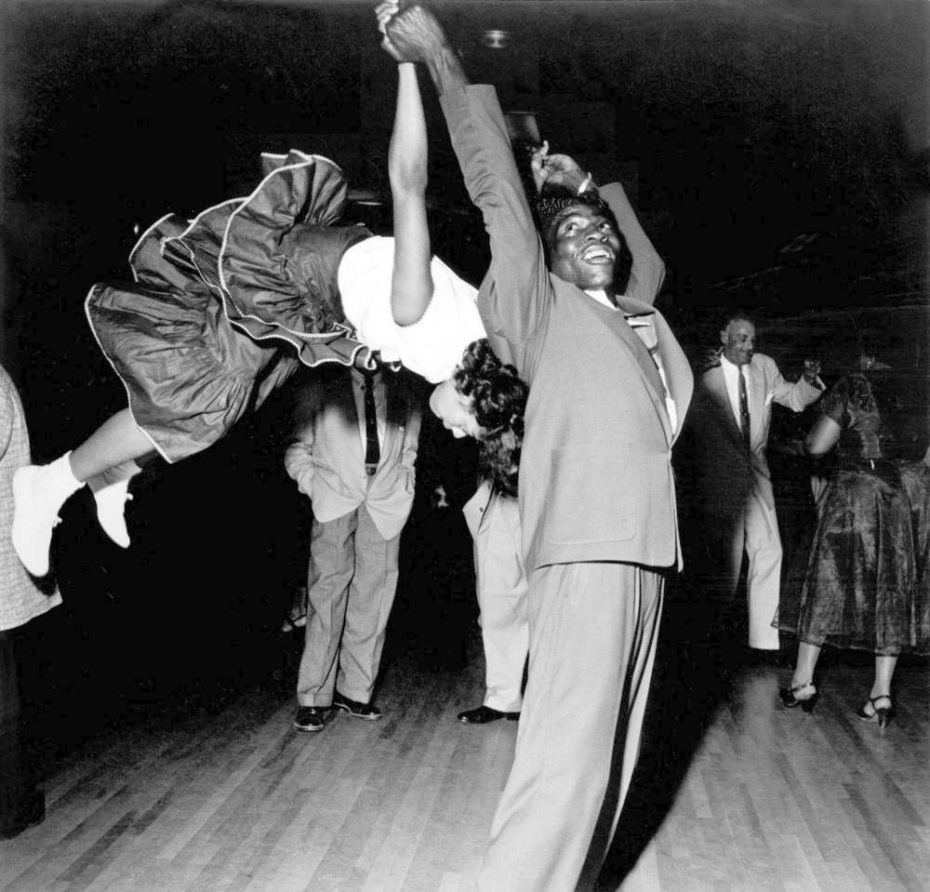

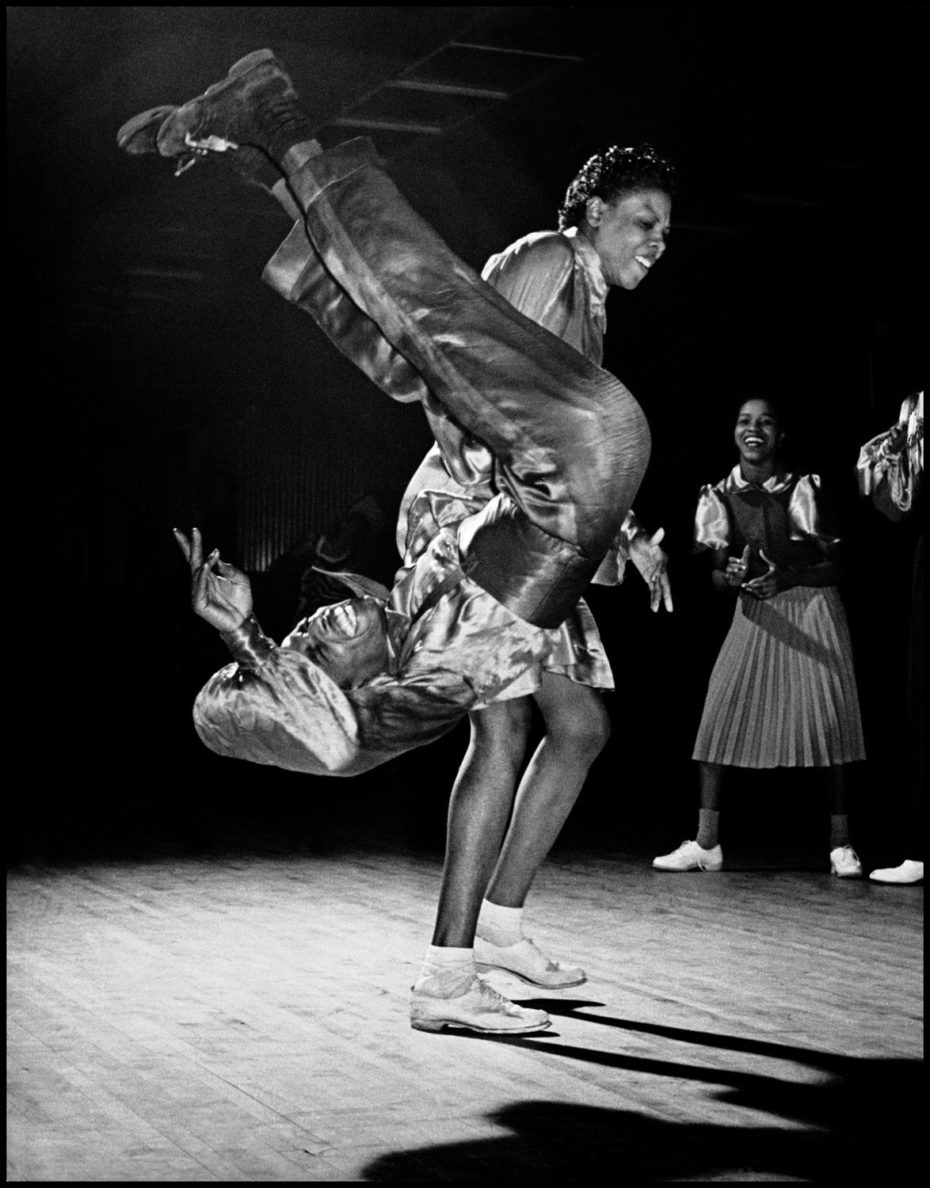

Shorty George formed a new amusing partnership with Big Bea, who stood a foot taller than him. On the opposite end of the spectrum, Tiny Bunch was a huge man, weighing over 300 pounds, and his partner Dot Johnson was a tiny waif. Too young to enter the Savoy, Norma Miller was dancing outside under the marquee when Twistmouth George whisked her in and they won a dance contest. After that, she was a Savoy regular, though she was just 14 years old. And then there was Frankie Manning, who flipped his partner over during a dance contest and created the first air step.

The Savoy Ballroom was soon so famous for the Lindy Hop that Buchanan was pestered with socialites who wanted Lindy Hoppers for fancy parties. Too busy to manage a dance corps, he turned to security guard Herbert White, nicknamed “Whitey” for his white streak in his hair. Whitey had demonstrated a keen eye for talent in dance contests since 1927. Tasked with creating an ensemble of dancers to represent the Savoy Ballroom, he formed Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers with the most talented dancers at the club, including Frankie Manning, Tiny Bunch, and Norma Miller. Most of Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers were Harlem teenagers, ecstatic to make a few dollars doing what they loved. Whitey also convinced Buchanan to reserve the north end of the dance floor for the best dancers to practice. It was soon called “the Corner” or “Cat’s Corner” and became legendary for acrobatic feats of social dance.

Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers were so popular, they hit Hollywood in 1936, appearing in the Marx Brother’s A Day at the Races. They most famously performed a jaw-dropping dance sequence in the 1941 musical film revue Hellzapoppin’ though the scene is marred by the maid’s outfits and workman’s clothes that they were forced to wear. Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers were so much in demand that Whitey eventually had 70 dancers in the ensemble, simultaneously performing at the Moulin Rouge in Paris, Radio City Music Hall in New York, a Broadway show, and celebrity-studded private parties.

Back at the Savoy, a star was on the rise. Ella Fitzgerald had entered one of the earliest Apollo Theater Amateur Nights in 1934 intending to dance, but at the last minute, she decided to sing. She won the contest and a one-week contract with the Tiny Bradshaw Band at the Harlem Opera House. There she met Chick Webb, who was looking for a singer. Their collaboration became legendary, resulting in songs like A Tisket A Tasket, a mega-hit in 1938 that showed they could make anything into a brilliant jazz standard, even a corny nursery rhyme.

On the night of May 11, 1937, Chick Web squared off against Benny Goodman in an epic battle of the bands. It was the King of Drums versus the King of Swing. Goodman’s orchestra also featured the drummer Gene Krupa, who was every bit as famous for killer riffs. Four thousand people crowded into the Savoy Ballroom to see the two bands duke it out. Buchanan called the police and then the firemen and then the riot squad to handle five thousand other people who could not get inside and refused to leave the premises. After hours of prodigious playing, the Chick Web Band was declared the winner. Krupa later said that Chick Webb “cut him to ribbons.”

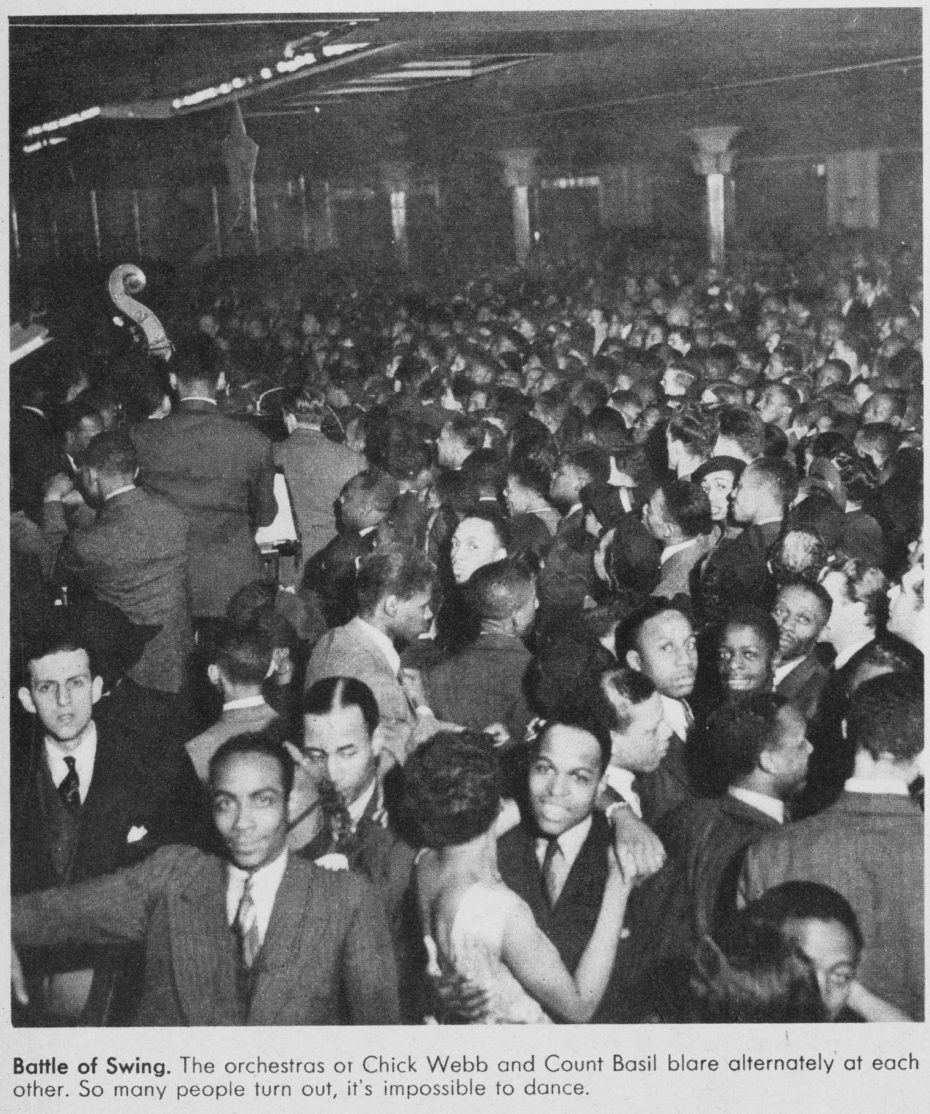

The Battle of the Bands was repeated on January 16, 1938 between Chick Webb and Count Basie. This time, the square off was also between Ella Fitzgerald, singing with Chick Webb, and Billie Holiday, who was part of Count Basie’s band. Downbeat Magazine reported, “Feeling ran very high between the supporters of the two bands and it was a fight to the finish.” The official verdict is that Chick Webb won, but to this day, people debate who won this Battle of the Bands.

Chick Webb died in 1939 from complications due to his chronic tuberculosis of the spine. At his funeral, attended by more 8,000 people, Ella Fitzgerald sobbed through the song My Buddy and his band was too emotional to play.

The Savoy Ballroom continued to draw huge crowds through the 1940s as the Lindy Hop became acceptable in mainstream society. Hollywood stars made their way through its doors. “Clark Gable just walked into the Savoy!” patrons outside would signal. But more importantly, the response was, “Can he dance?”

Several members of Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers were featured in a Life Magazine page spread in 1943. By then, most of the men in Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers had been drafted into World War 2 and the ensemble eventually disbanded. There was also a riot in Harlem in 1943, which led to a the Savoy Ballroom being shut down for several months on vice charges. “Harlem said the real reason was to stop Negroes from dancing with white women,” avid Lindy Hopper Malcom X later wrote in his autobiography, “Harlem said that no one dragged the white women in there.”

The Savoy Ballroom celebrated its 25th anniversary in 1951. That year, the city announced a slum clearance housing project that called for the demolition of all the buildings bounded by Lenox and Fifth Avenues and 139th and 143rd Streets. The Savoy was part of this area and so was the Cotton Club. No one really believed that the Savoy Ballroom would close, even when all the other buildings on the block were demolished in 1953.

Protests and a letter-writing campaign to save the Savoy Ballroom failed to convince city officials to halt the housing project. In September 1958, the Savoy Ballroom closed and its luxurious furniture and lighting fixtures were auctioned off. The building was demolished a few months later in 1959 amidst negotiations for a new Savoy Ballroom to open elsewhere.

The closing of the Savoy Ballroom left a hole in Harlem that has never been filled. In 2002, two former members of Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers, Frankie Manning and Norma Miller, unveiled a plaque where the Savoy once stood to commemorate its lasting contributions in music, dance, and the integration of public venues in America. The music lives on and so does the dance. Both Manning and Miller were a huge part of the Lindy Hop revival of the 1990s, passing the baton to a new generation.

About the Contributor