The sensational peacock first made landfall in Europe about twenty centuries ago when its sparkling, bedazzling image was captured in the glistening mosaic floors and walls of the Romans and Byzantines. Imported from their native India, they were anointed the holy birds of the goddess Juno and kept in her temple. Fast-forward to the 15th century, and they were again spotted in the plumes of knights in their shining armoured helmets and in the 18th century, it wasn’t unusual to find an imported peacock roaming a country estate lawn, an exotic novelty for the privileged to admire. Despite making somewhat of an impression throughout various moments in history, it wasn’t until the 19th century that the peacock would take centre stage as the unofficial mascot of Art Nouveau.

The male Indian peacock has the iconic long tail feathers punctuated by those ever-so-characteristic ‘eyes’; the females, or peahens – unlike their cocky male partners – didn’t win the good looks lottery and are duller and smaller, with no tail or train feathers. It’s believed the female is not only attracted by the number of ‘eyes’ but also the impracticality of the male’s body. Darwin went on to suggest that the oversized cumbersome tail and the over-advertised brightness of the body were the ultimate proof of the ability to survive predators and life’s challenges, therefore undeniably attractive to prospective mates. But as for the incomparably iconic peacock as an object of design and desire, the bird was from a world outside of historical Europe, and its distant and obscure origins had provided the subject of enduring lore.

The ancient Greeks and Romans, intrigued by the creature’s metallic and iridescent plumes believed it to be immortal as it seemed to be able to eat poison and survive. Indeed it is now thought that it is the bird’s ability to eat unusual foods that fuels its extreme colouration (a little like it’s decorative counterpart, the flamingo or phoenix, that achieves its characteristic pink colour by eating volcanic algae). But they never quite managed to find an artistic expression or iconic convention for the peacock in their arts and architecture pattern books in the way that they employed the likes of eagles, lions and their ever-present curly acanthus foliage. Thus, the peacock remained outside the visual arts mainstream for centuries, until its mass migration into the 19th century Victorian colonial world.

It arguably all started happening for the almost-perfectly ‘designed’ peacock in London. The bird made a profound public appearance in the high Victorian arts & crafts world of 1876 as the subject of painter James McNeill Whistler’s foray into interior design at a private home in Chelsea. The Peacock Room (subsequently and famously hated by his client) featured ostentatiously painted solid golden peacocks crashing and disintegrating across the petrol blue walls. Regarded as ridiculous, the room was demolished just 28 years later and shipped to America where it now stands in the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington.

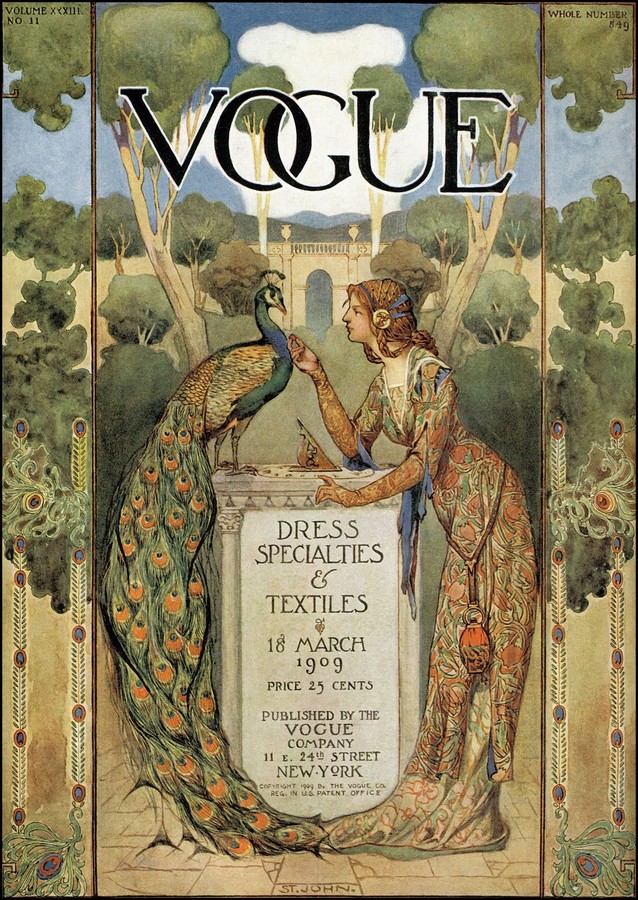

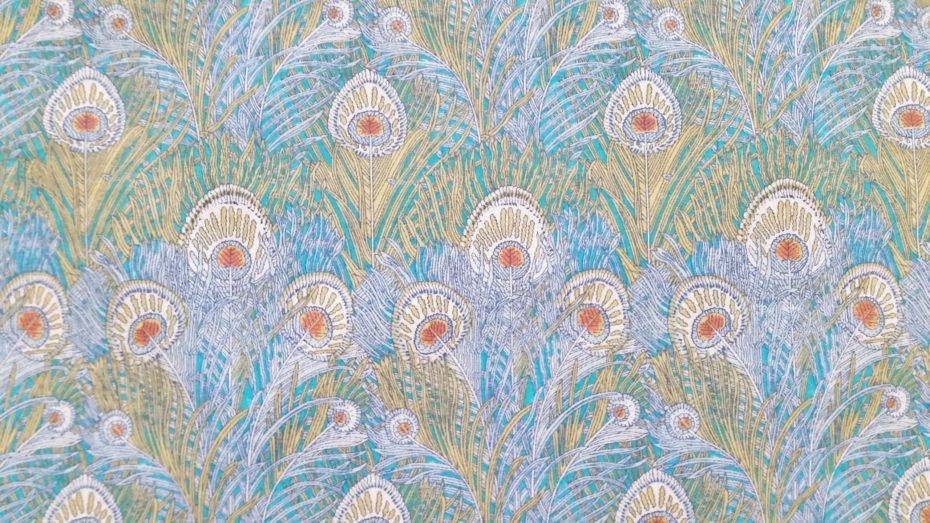

But only a few years later in 1887, one of London’s first department stores, Liberty of London, named their newest feather pattern (a print that’s coveted, reproduced and in vogue to this day) after the Greek goddess Hera, whose chariot was pulled by peacocks. The store itself was founded on bringing goods from the East to the West via European-Asian sea route at the height of the British Empire and Liberty’s would go on to champion the burgeoning Arts & Crafts and Art Nouveau movements in Europe – so much so that in Italy, Art Nouveau was first referred to as the “Stile Liberty”.

The peacock became a favourite of the British Arts and Crafts Movement, notably of William Morris and his circle who sought a new aesthetic language based on natural forms. The rich colours and swirling feather patterns of the peacock were perfectly suited to the interlaced foliage designs for wallpapers and fabrics of the Arts & Crafts Movement, which was the springboard for the subsequent Art Nouveau Movement. Sumptuous peacock feather designs adorned ball gowns, paintings and ceramics as the bird edged its way into Victorian society.

The peacock then managed to fly across the channel to roost in Art Nouveau Paris. France would see the blossoming of Art Nouveau in the later Belle Époque era, lasting from the 1890’s to the outbreak of the first world war in 1914. It would go onto to be a very much European continental arts movement, albeit for a niche privileged clientele from Estonia to Spain. The artists and designers, on the hunt for something new and in seeking the curvaceous and twisting lines of nature’s flora and fauna, had discovered the most perfect and divine shape of them all: the universally inspiring and glamorous peacock. From jewellery to fabrics, from painting to architecture, Art Nouveau couldn’t get enough of this majestic bird.

Designed by L. C. Tiffany, 1890

René Lalique, a Parisian jeweller’s amazingly intricate nature-based enamel-and-gold jewellery proved a perfect medium for fanciful peacock creations such as pendants, rings and brooches. Bright and vibrant-coloured enamels and gold mounts reflected the sparkling and contrasting mix found on the male peacock himself. Across the Atlantic, in New York, Louis Comfort Tiffany would famously exploit translucency through the use of coloured stained leaded-glass with peacock imagery in their exquisite lampshades.

Hector Guimard’s Paris Metro Station entrances took the peacock’s fan-tail to the built extreme with fine, sinuously radiating metal work supporting feather-like glass canopy panels while in 1908, Russian jeweller Carl Faberge produced the most exquisite of all his eggs: a miniature enamelled peacock, sitting in a tree inside a hinged translucent egg.

The peacock continued to serve Art Nouveau in all its design guises, appearing in construction – ironwork, railings and gates – as well as many other aspects of design across Europe. But Art Nouveau and the Belle Époque era came to an end with the outbreak of World War I in 1914. By 1918, with the end of the exhausting war, European economies with the need for radical social change no longer had an appetite for such an indulgent movement.

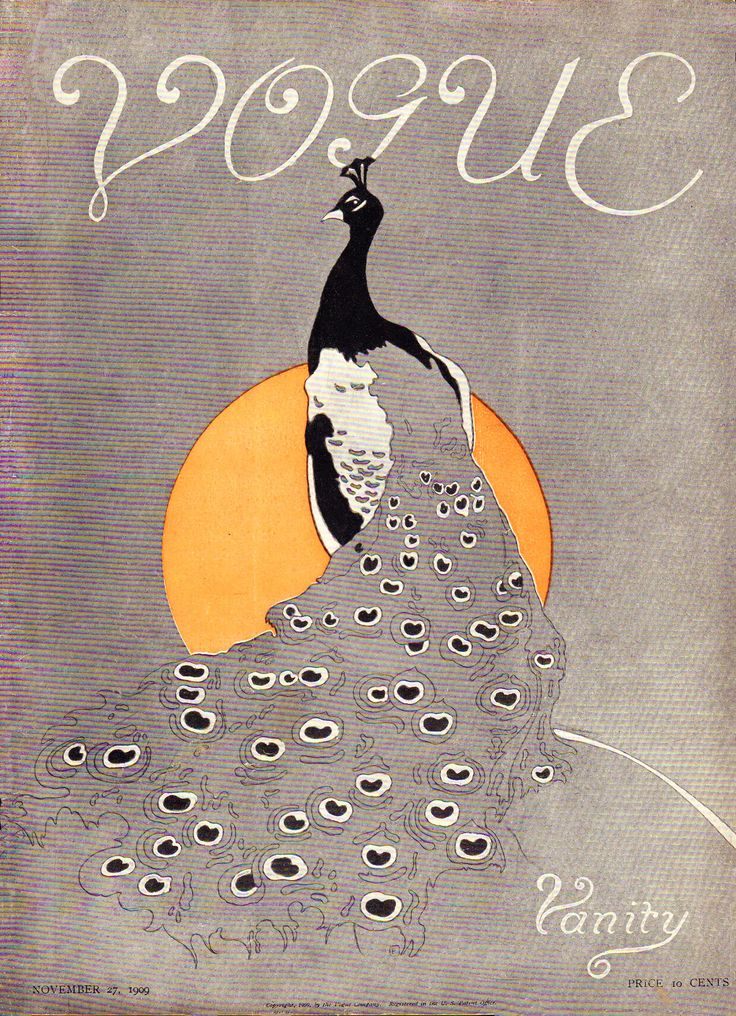

The peacock may have had its day with jewellers, painters and sculptors, but through fabric and dress it would live on and be available through mass production to greater society. The Liberty & Co peacock print fabrics would live on in fashion, which in turn would be exploited in the new media of film. Lavish and sumptuous peacock patterned ball gowns would grace the early 1920s’ world of cinema and theatre, perhaps as a last deja vu to the lost glamour of the Belle Epoque, but also flying the peacock into a new era.