In the waters of the Caspian Sea, about 40 kilometers from the coast of Azerbaijan, lies an intricate network of bridges and man-made platforms which is currently home to around 2,000 people. Encompassing about 17 miles, this real-life water world is a veritable city called Neft Daşları (Neft Dashlari or Oily Rocks). It’s sole purpose is industrial, it was the first offshore oil platform ever built, but it’s now slowly decaying and will one day disappear entirely.

Azerbaijan is a nation which straddles the line between east and west. It borders Russia, Georgia, Armenia, Turkey, Iran, and the Caspian Sea. In 1949 is was a part of the Soviet Union, and was called Azerbaijan SSR. As far back as the 3rd and 4th centuries there is evidence of the trade in petroleum. Arabic and Persian scholars describe the trade frequently, as do later visitors to the area. In 1683, Secretary to the Swedish Embassy, Englebert Kaempfer, made a point of detailing the gaseous smell and fires emanating from fissures in the oil fields. Oil production sped up rapidly in the late 19th century, and by 1901, Baku (Azerbaijan’s capital) was producing more than half of the entire world’s oil supply, and it all came from wells that were within 6 miles of one another.

This richness couldn’t last. With the Russian Revolution in 1905 causing a drop in oil production and then further catastrophe during WWI, oil production plummeted. Azerbaijan’s independent government (which was only in place from 1918-1920) could not jumpstart it again on their own. The Bolsheviks had seized power in Azerbaijan, and rerouted all oil to Russia. The country that was both east and west desperately needed innovation and power in order to restore their petroleum industry. Enter the USSR.

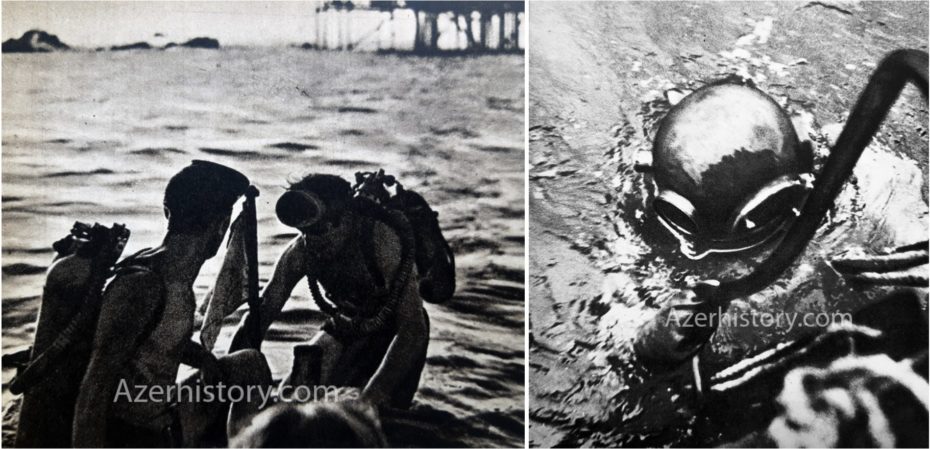

In the late 1940’s geologists had been busy surveying the area in the Caspian Sea, suspecting that there was an oil deposit. In 1949 they were proven correct, and construction began on creating the necessary infrastructure for people to work on water. In the beginning, Neft Daşları was built on seven sunken ships, including the very first oil tanker in the world, but this outpost, which was situated over a very rich oil deposit only 1,100 meters below the seabed, grew rapidly from its discovery in 1949 to the start of its drilling operation in 1951.

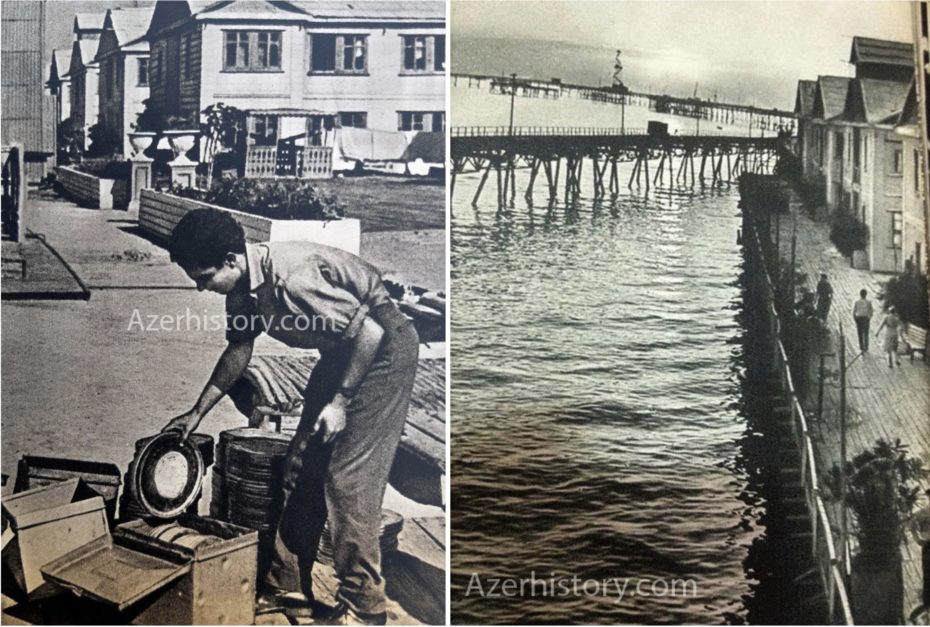

Soon more “islands” were built, mostly from soil and landfill. Trestle bridges connected everything, and they built a cramped and complicated system to get oil from the drilling sites back to land. They had built the world’s first operational off-shore oil rig and the floating city grew exponentially. At it’s height, Neft Daşları had around 2,000 drillings platforms pulling from the underwater oilfields.

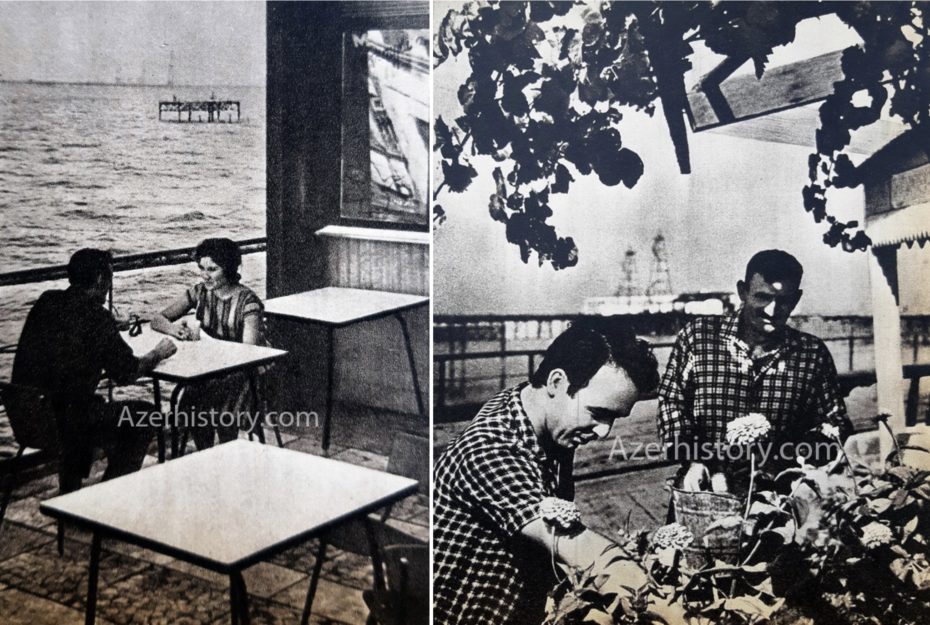

A staggering 300 km of bridges were erected in the middle of the Caspian Sea with apartment blocks and buildings multiple stories high, bakeries, soccer fields, parks, cinemas, cafes, and cultural spaces. The residents began to cultivate soil from the mainland in order to grow their own fruits and vegetables. The population soared to 5,000. In short, life on the city of “oily rocks” was bustling.

In the late 1970’s Neft Daşları experienced another boom, which led to underwater pipelines, an airway for transporting vehicles to the city, and (perhaps the most exciting to the residents) a way for the city to supply itself with fresh drinking water.

Change came again to Neft Daşları when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. Azerbaijan had declared its independence from the Soviet Union just a few months before the fall. New oilfields were cropping up around the globe. There was fierce competition from drilling fields in places like the United Sates, Mexico, and Kuwait. The city’s population began to dwindle, and so did the infrastructure. Seawater began to reclaim parts of the city. Today, the population has dropped to around 2,000 and out of the 300km of roads there once were, there are only 45 km are still useable. Some of the ships have become unusable as the bridges leading to them collapsed.

A large flood in recent years also took out the first two floors of some of the apartment buildings. Jagged steel beams crisscross below the water, making it dangerous for ship to move around. Workers are paid more than they would be on the mainland, but they are finding themselves on an increasingly crumbling piece of Soviet history.

In 2009, when the city of oily rocks celebrated its 60th anniversary, some 170 millions tons of oil and natural gas had been produced since its founding. From the mid-20th century on, and throughout the uproar of the rise and fall of the Soviet Union and beyond, this city has defied convention and stood its ground in the sea. In a country known for its industrial output Neft Daşları has been a curiosity of human ingenuity. And there is still oil beneath the seabed. Experts estimate that there is probably around 30 millions more tons, or about 30 more years worth of drilling, but eventually the oil reserves will dry up, and the city will almost certainly collapse back into the Caspian Sea. The question is how quickly will this happen, and how will the residents reintegrate back to life on the mainland? Take also into consideration that this city is something of a terribly kept Soviet secret. Foreigners have an extremely hard time gaining access, and the city does not appear on Google earth (we tried).