Ah the psychedelic 60s, what a time to be out of your mind. It’s easy to assume bohemian beatniks, free lovin’ hippies, and prog rockers popularised mind-bending medicines to everyday folk, but let’s go back a step before we start spiralling. Who’d have thought that American counterculture was kickstarted in the most conforming of places, the suburbs. Shoes off at the door, you’re invited round for dinner with those nice normal neighbours next door. On the menu? Mushroom surprise!

Meet Gordon and Valentina Wasson. He’s a New York banker and she works as a paediatrician. After a few drinks, ask them about their honeymoon in the Appalachian Mountains, it was quite the trip. In 1927, the freshly wed lovebirds stumbled upon some intriguing woodland grub while on holiday. Valentina, originally from Russia, was keen to get stuck into her foraged food, but Gordon had reservations. Fascinated by their diverging cultural attitudes towards funky fungi, the couple wanted to dig deeper into the taboos.

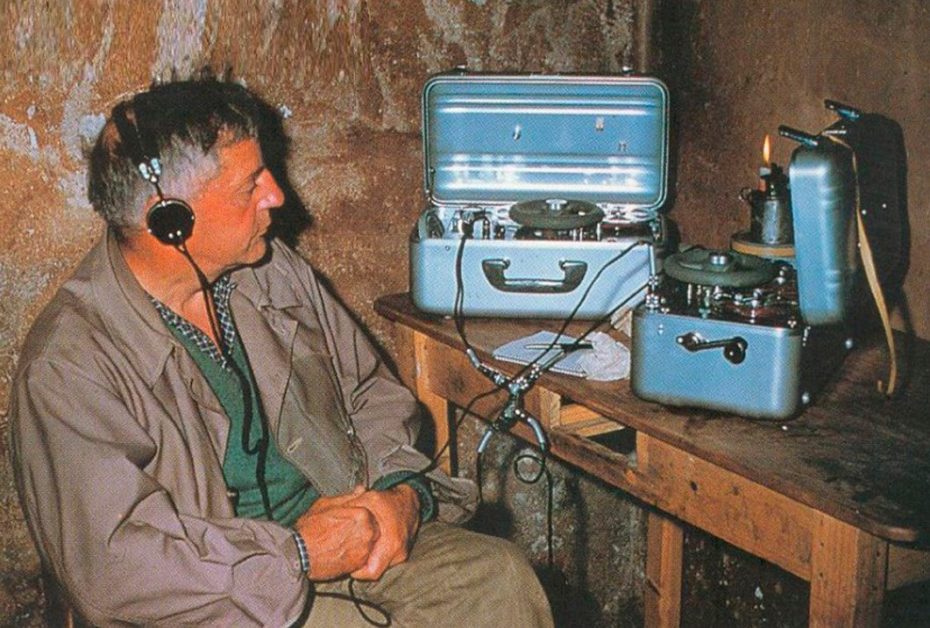

Since this moment, the Wassons quietly carried out field research into the history of fungi in ancient folklore, art and religious traditions alongside their day jobs. They sent letters to missionaries, shamans and anthropologists around the world to learn more about their burgeoning interest.

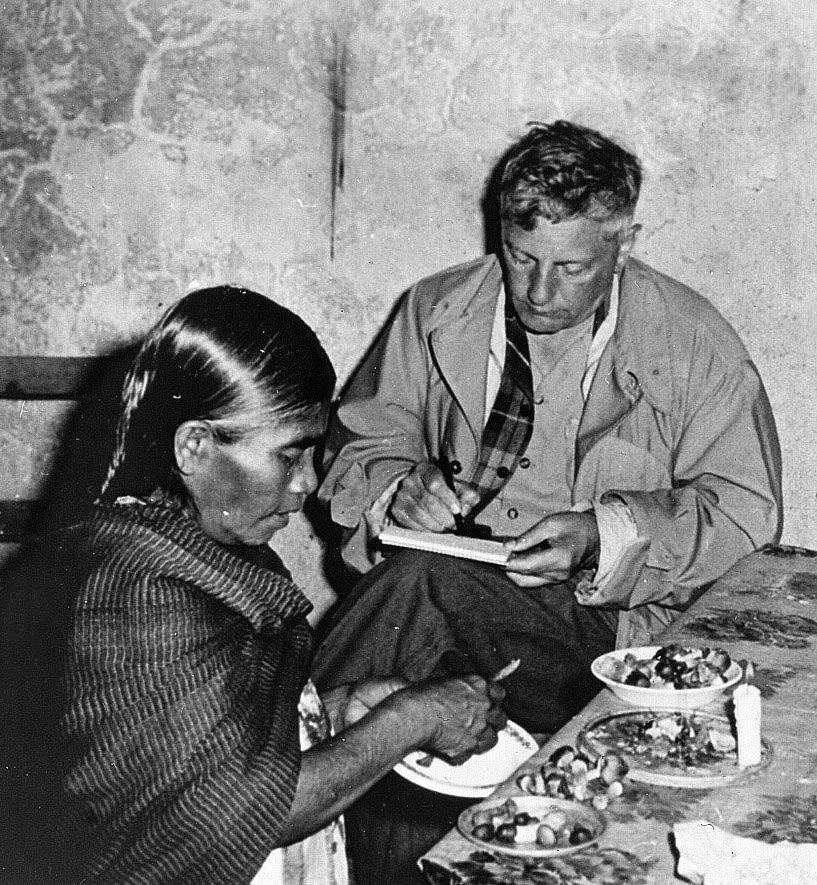

Gordon and Valentina soon became obsessed with their new hobby. The pair went on regular expeditions to Oaxaca in Mexico to study the religious use of wild mushrooms by native populations. In 1955, at the climax of their research, the couple took the plunge and tried psychedelic fungi, psilocybin, for themselves. In doing so, they became the first Westerners to participate in a Mazatec mushroom ritual. Two years later, on the sly they published their findings in a hefty academic book, limited to 500 copies.

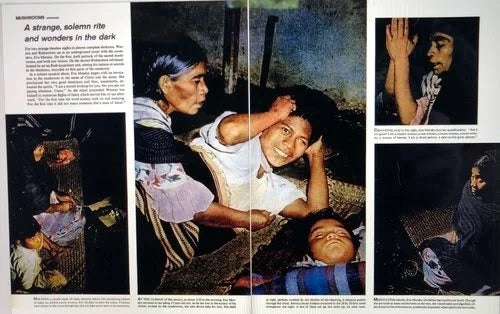

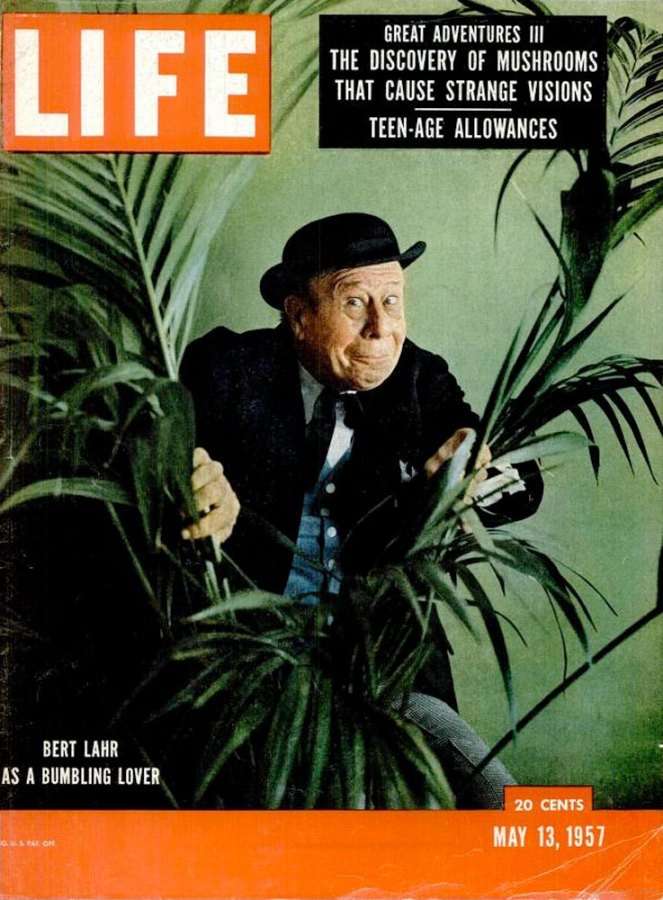

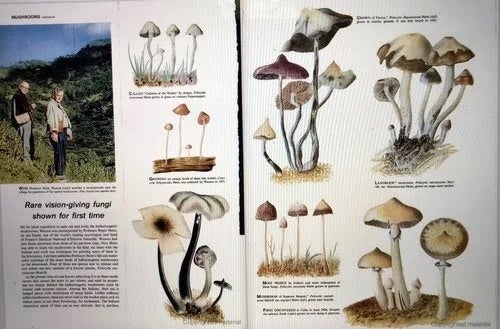

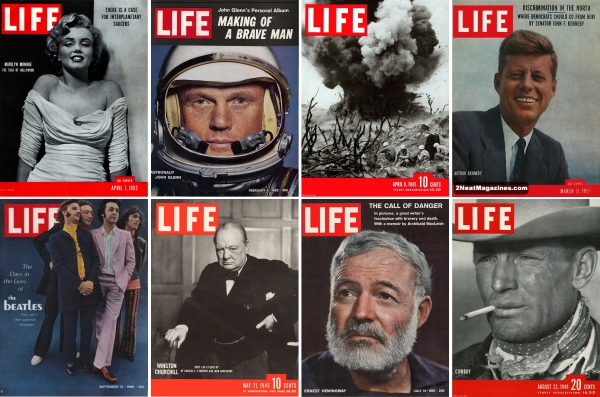

The turning point came in May 1957 when the couple’s secret passion project was outed to their colleagues at the bank and the hospital, as well as all of America. Gordon penned a photo essay entitled ‘Seeking the Magic Mushroom’ for Life magazine, during the heyday of the publication. In the piece, he details his hallucinogenic high, including visions of mythological beasts, melting walls, measureless seas and his spirt leaving his body to the sound of ritualistic chanting. ‘For the first time, ecstasy took on real meaning’, he says. Alongside his vivid descriptions, readers could peruse photographs of his Mexican trip and illustrations of several shroom species to identify for themselves.

In the 1950s, Life was the most prominent magazine on newsstands, with its popular audience being the average American. It was a favourite with suburbanites who related to the conservative tone and aspirational products advertised between articles. Powerful in its persuasion, it entered the homes and minds of millions of Americans each week and became a topic of community chitchat due to its extremely high ‘pass-along’ rate.

Gordon’s 20-page spread on ‘bathing in the supernatural aura’ of fungi was ground-breaking. They say something becomes mainstream when it reaches the normies. By connecting with outer towners, psychedelic shrooms spouted from the fringes to the centre stage of popular American culture.

Suburban families of the 1950s recognised the type of strait-laced guy Gordon was and related to his banker-next-door aesthetic, giving his words an air of respectability. It’s easy to imagine whisperings of ‘Did you hear about the Wassons?’ as lawns were mowed and cars washed. What’s more, the description of his out of body experience being like a ‘disembodied eye, invisible, seeing but not seen’ sounded ideal for seasoned curtain twitchers. An intriguing upgrade from popping a Valium to escape the tedium of life in the ‘burbs.

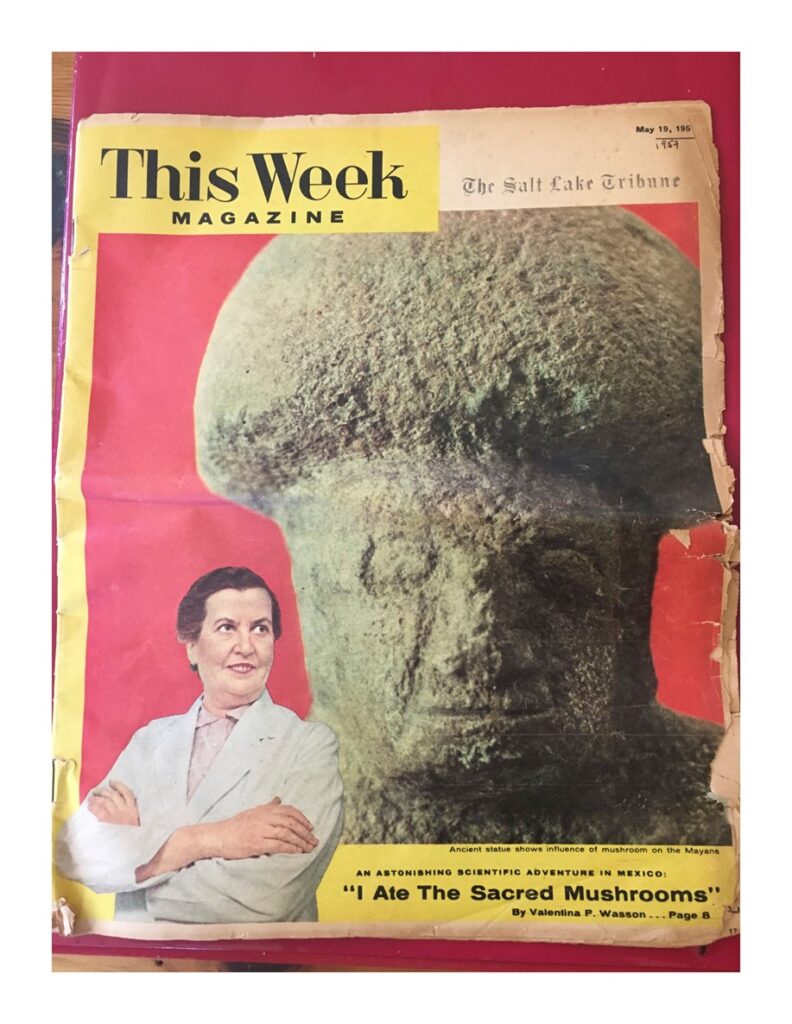

For an even greater hit of the good stuff, Gordon’s essay was followed six days later by his wife’s first-hand account of their expedition to Mexico. Valentina’s debut, titled ‘I Ate the Scared Mushroom’ featured on the cover of This Week, a Sunday magazine inserted in 37 newspapers that reached almost 12 million Americans.

Over eggs and bacon, readers once again spat out their coffee as they learned about her technicolour visions of ‘a ball in the Palace of Versailles with figures in period costumes dancing to a Mozart minuet.’ The fact that all this was coming from a female paediatrician, someone they would trust with their children, gave power to her account as a medical discovery rather than just a surreal piece of literature. Valentina wasn’t simply a thrill seeker. She suggested that psilocybin mushrooms might be used as a psychotherapeutic agent, making her one of the first to advocate for their use in the treatment of alcoholism, mental disorders and chronic pain.

The Wasson’s work led to great advancements in mycology, medicine, and anthropology, so much so that two species of shroom were named after them. Of course, they didn’t discover magic mushrooms – tribal cultures had known about their healing powers for centuries – but they certainly did bring them to the western masses. Their years of research, sending spores off to labs for investigation, and writing back-to-back articles were no doubt the reason for the popularisation of flower power fungi within the general American population, be that for better or for worse.

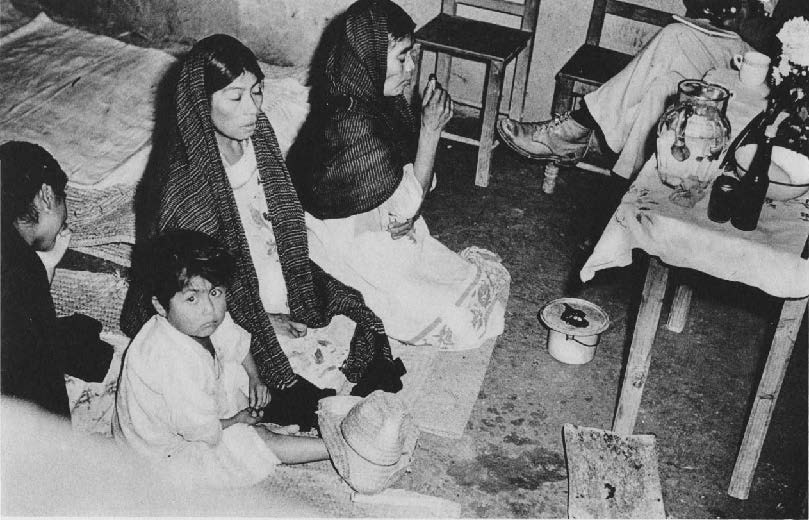

The mushrooming interest in Mazatec rituals initially proved disastrous for native communities, in particular one woman called Maria Sabina. Maria was a spiritual healer in Oaxaca who allowed the Wassons entry into her secret world of sacred mushroom ceremonies, known as veladas. Although Gordon and Valentina redacted the names and places of their enlightening experience to protect their privacy, it didn’t take long for word to get out.

After rumblings in the ‘burbs for a couple of years, experimental hippies and beatniks with less to lose sought out Mexican shamans in the early 1960s. Maria Sabina was inundated with requests from travelling tourists chasing the elusive high, contradicting the purpose of her veladas which was to cure the sick. It is claimed that Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan and John Lennon managed to track Maria down too. This popularity unfortunately led to the pollution of the traditional tribal practices and police intervention in the community.

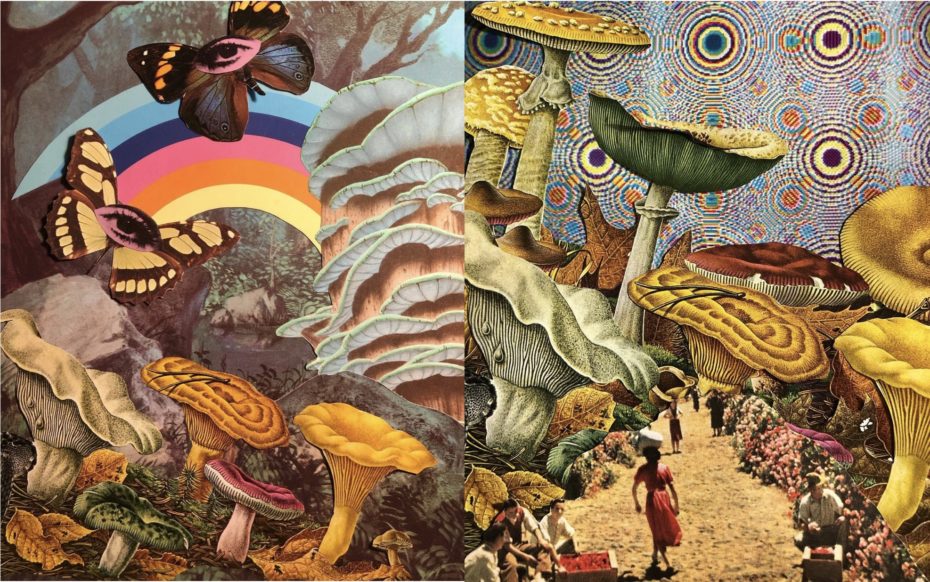

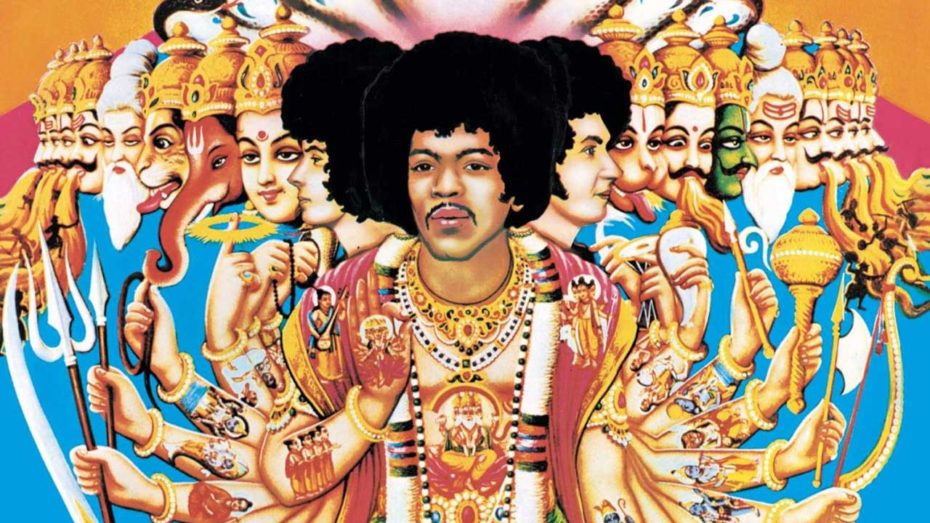

Although they didn’t get there first, these groups of freewheelin’ and free lovin’ folk came to serve as evangelists for the psychedelic revolution. The countercultural movement in the 60s became tangled up in love with the unexpected magic of mushrooms. Its influence can be seen in art, philosophy, music and fashion of the time, without a mention of Maria or the Wassons.

A decade later in the 1970s, Gordon Wasson did own up to being the white guy that ruined something special. He stood by his research in the name of scientific discovery but did express remorse for how the wide publicity impacted the Mazatec culture and the traditional mushrooms rituals. Committed to the cause however, the married couple dedicated the rest of their lives to this neglected field of study, even when the tide turned against them and psychedelic drugs were made illegal in 1970. Along with Maria and her community’s generosity, they are responsible for many a psychedelic summer of love.

Next time you spy folk foraging for suspicious looking shrooms in the forest, hear the twang of a Jimi Hendrix guitar solo or witness a flower power fashion revival, just remember how it all started. Behind closed doors, as an inspiring illicit side project, that got all of suburbia cooking up a storm straight from the pages of their Sunday magazines.