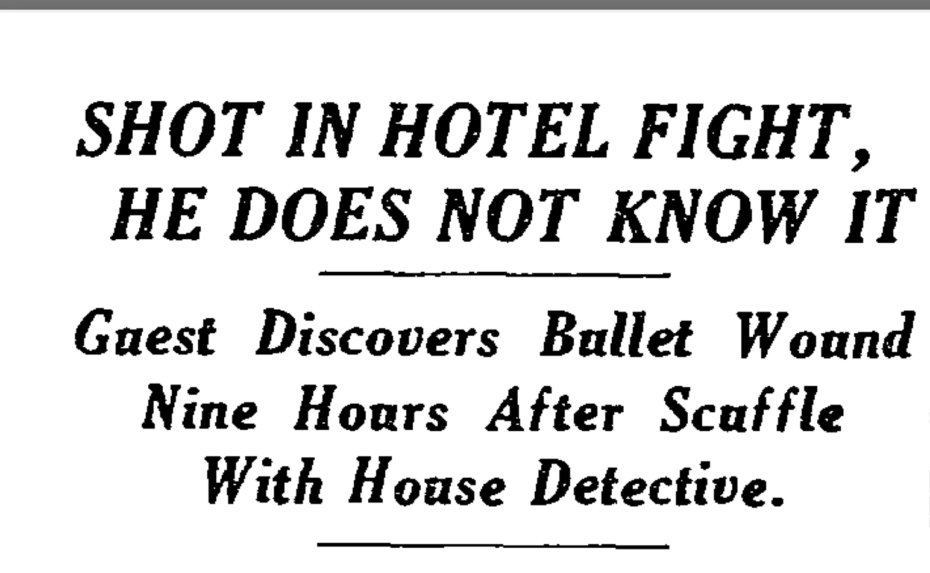

“Saverio Bongiorno had no permanent home and had been living in various midtown hotels. Bongiorno registered at the Edison Hotel on Sunday, with a small beach bag as his only baggage. He was assigned to room 1135 and nothing more was seen or heard of him…James Gerrity, chief house detective of the Hotel Edison, 224 West Forty-Seventh Street…went to room 1135, knocked repeatedly and then decided to enter with his pass key. Just as he started to insert the key, the door swung violently open and Bongiorno confronted him with a .38 calibre pistol in his hand.” This may sound like an excerpt from the hard boiled fiction of crime novelists like Raymond Chandler or Dashiell Hammett, but it is actually an account from the New York Times, January 1935. It gives a tantalising glimpse into the vanished world of one of the great lost professions : the hotel house detective.

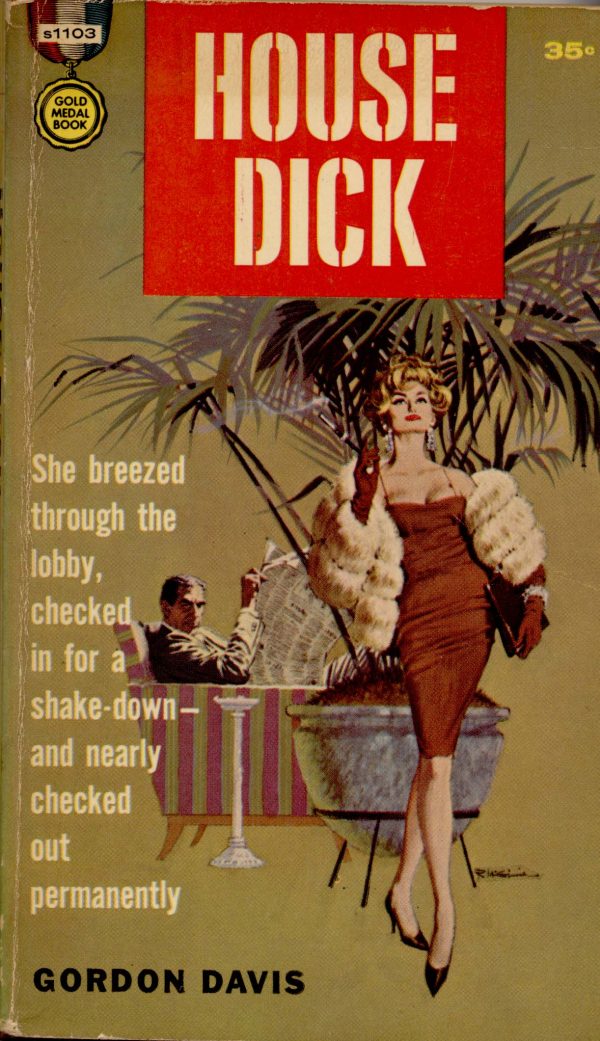

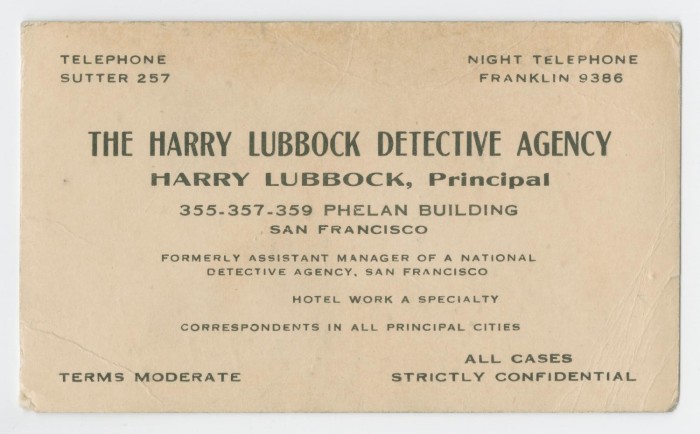

Up until not quite so long ago, it was common practise for most grand hotels to keep on their books, alongside the porters, elevator attendants, chefs, chambermaids and bellhops – an in-house detective. As much a staple of 1940’s film noir and pulp fiction as the femme fatale, these ‘house men’ were very much real professionals working within the hospitality industry, and could be found in hotels all over America. A far cry from modern security guards and bouncers, they were often retired city policemen, who would draw on their years of experience to prowl the corridors and survey the lobby to protect both the guests, and the reputation of the hotel. Join us as we peek behind the plush curtains of a luxury hotel, and venture into the world of sneak thieves, confidence men, female prowlers, come-on girls, mashers, and the grizzled hotel detectives employed to stop them….

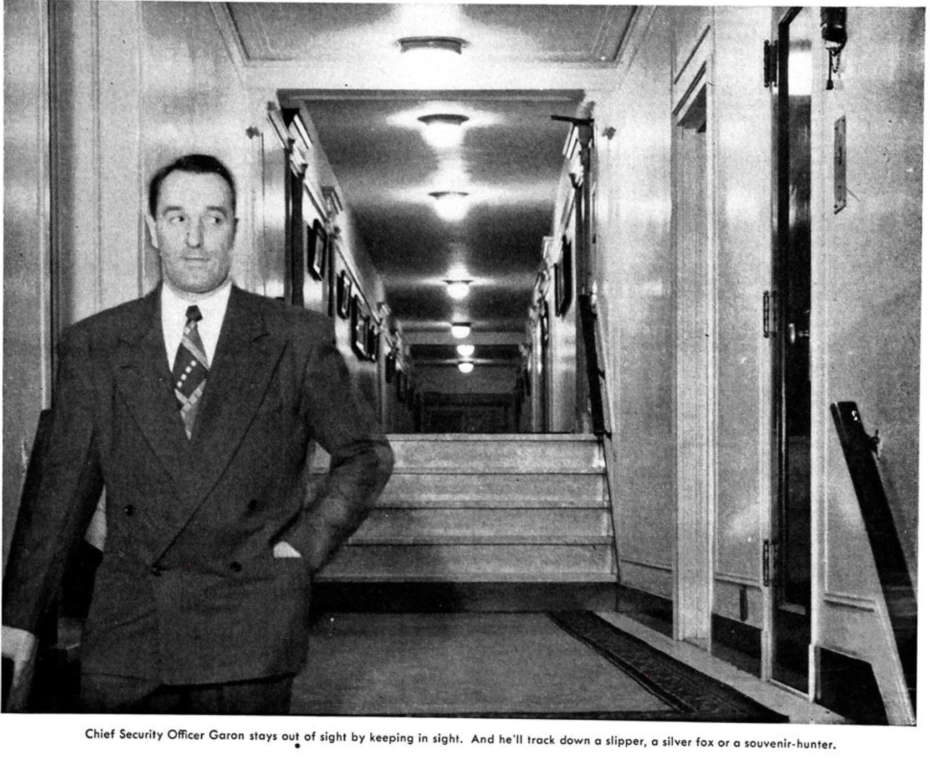

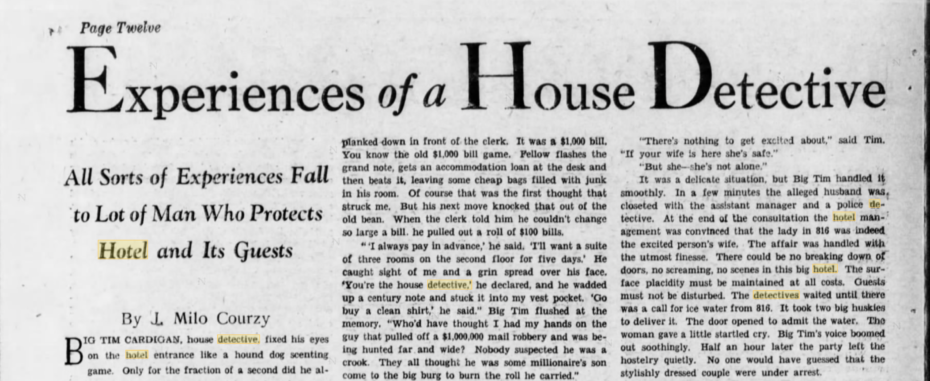

The cliché of the “hard boiled” fictional house detective was usually a hard drinking old gumshoe, sitting in the lobby and peering over his newspaper, before skirting past the potted palms to take up his regular seat at the bar. In real life however, the profession was hazardous and involved long hours, requiring true skills. As the New York Times reported in an exposé titled “Hotel Detectives and their Experiences” published in 1902, “Private detectives in the large hotels in New York are supposed to have very easy berths. As a matter of fact, they are the hardest working men to be found.”

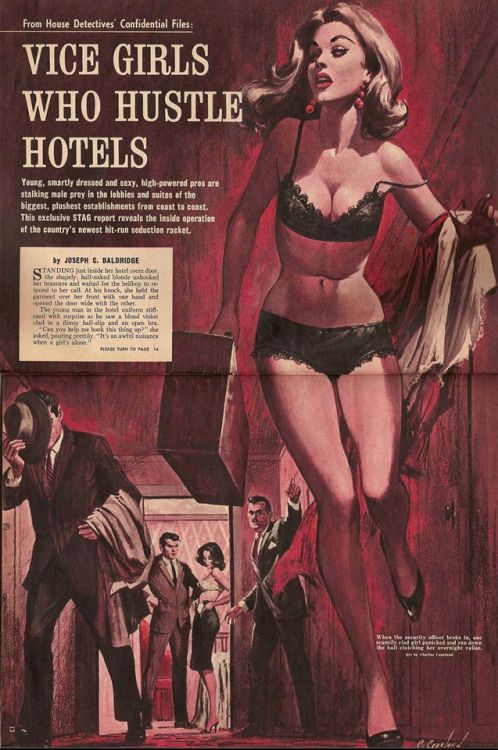

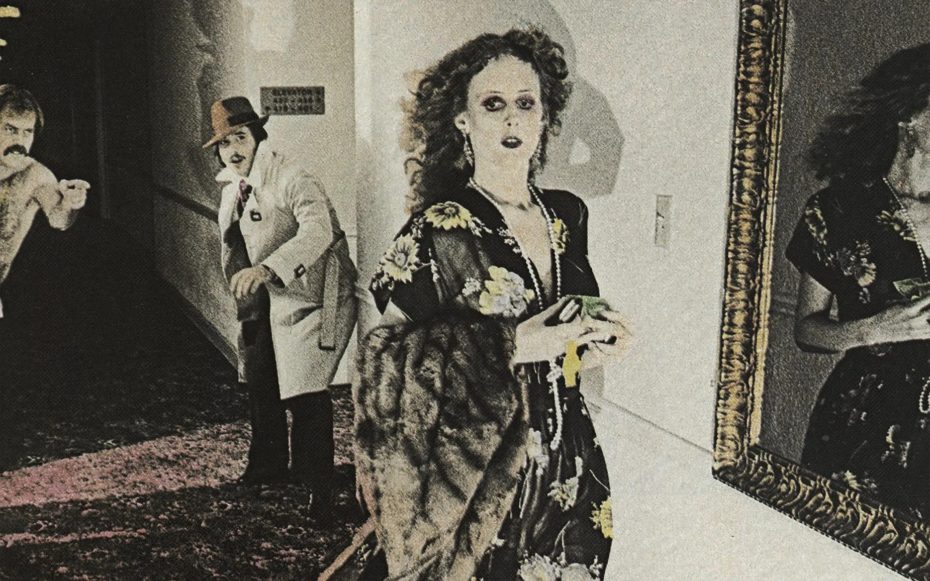

This was an era before closed circuit television and all-seeing security cameras; before hotel rooms came complete with their own small safes; and when unmarried couples checking into a hotel was still considered a scandal, or when the presence of working girls could sully the good name of a grand hotel. Over at the historic Adolphus hotel, built in Dallas in 1912, one reporter followed house man and ex-Dallas cop Charlie Coyle on his night shift. “The constant battle: the women depend on getting into the hotel for their livelihood, the detectives depend on keeping them out for theirs.”

One of the key skills to being a successful house detective was shrewd observation and judge of character, the talent to spot a chancer amidst the endless flow of genuine guests; or as the reporter shadowing the Adolphus’ house man put it, “While you’re checking in, he checks you out.” As far back as 1871, the NYT was reporting on the experience of checking into a hotel, and coming into contact with the ‘Quiet and Unobtrusive Way of the Hotel Detective’:

“You go in, and finally finish with the book-stand, the bar-keeper, the card-writer, when you think about one person who has always been an enigma to you. He has been in the house as long as you can remember it. You have noticed he had a very fascinating eye, a glance that took you in at a single wink. And sure enough there is the mysterious gentleman. After dinner, while enjoying your cigar, you see him in the reading room, gazing with a fixed intensity on the passersby. Our old friend was the hotel detective.”

Being able to spot the subtle signs of a potential ne’er-do-well across the lobby was essential. At New York’s opulent Plaza Hotel in 1911, the house detective spotted one guest whose “manners were very good, except he handled his fork upside down. But when he put sugar in his claret, he became an object of suspicion.” Already the house detective had his beady eye on the guest. “If he isn’t a crook, he’s a dangerous lunatic,” was the house man’s verdict.

The best hotel detectives used an army of informants drawn from the hotel staff. In the days before CCTV, bellboys, chambermaids and porters were valued eyes. Back at the Plaza, a chambermaid reported to the house detective that the sugar sweetened claret drinker had initials monogrammed on his clothes that were different to those on the register. The house detective swiftly ushered the guest into the hotel manager’s office, where it transpired that he was simply traveling under an assumed name as, “he thought it merely smart to keep his name out of the newspapers and enable him to see life without his wife’s finding out.”

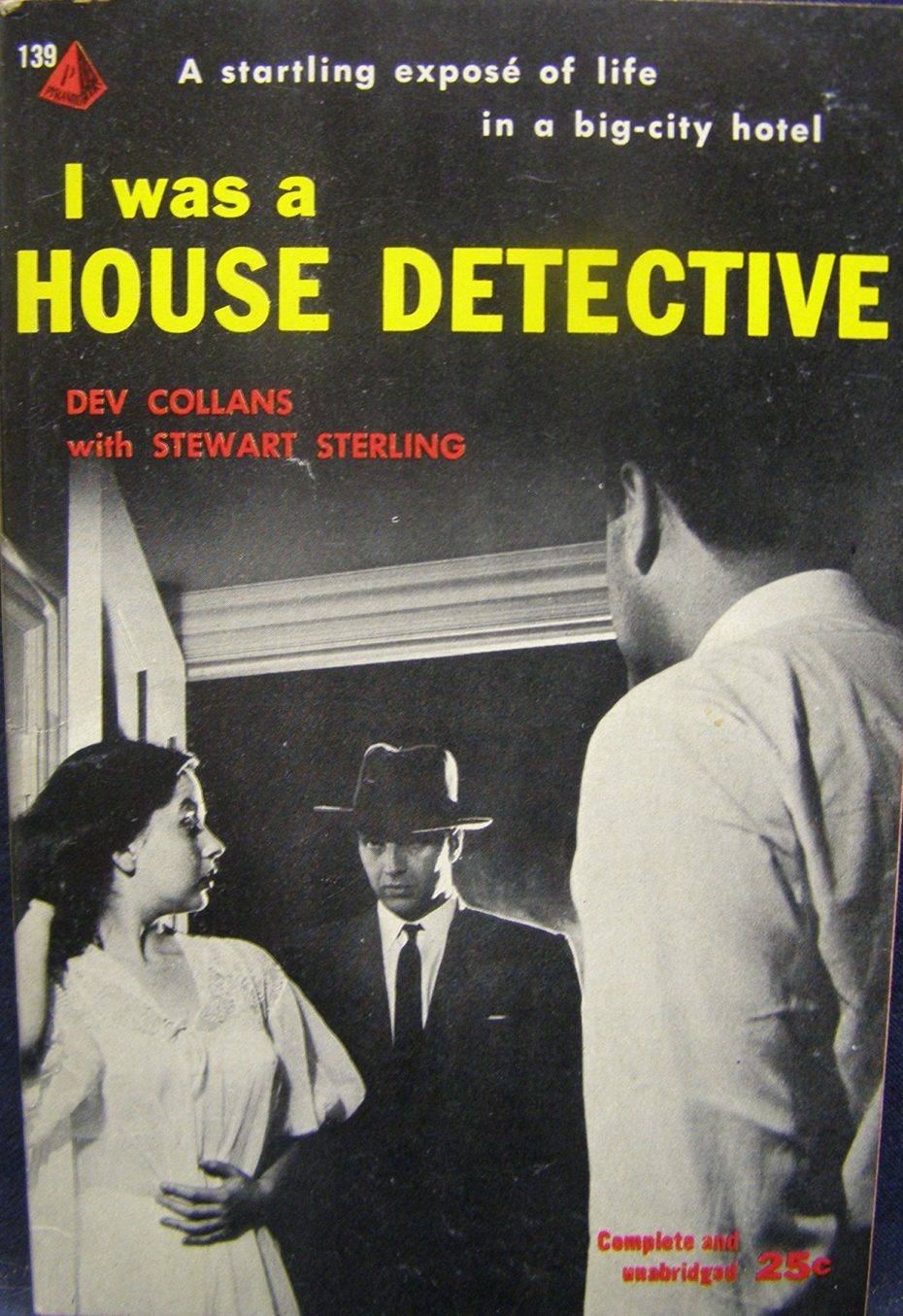

In his 1954 memoir, “I Was A House Detective,” Dev Collans described how he would enlist bellboys to keep an eye on couples as they checked in. “Couples who wouldn’t open their suitcases while the bellboy was in the room” was one give-away Collans explained, “Married couples didn’t hesitate to.” Collans would keep a sharp eye on guest’s footwear as well; “ A man in sleek clothes with a woman whose shoes were run down at the heels is another giveaway.”

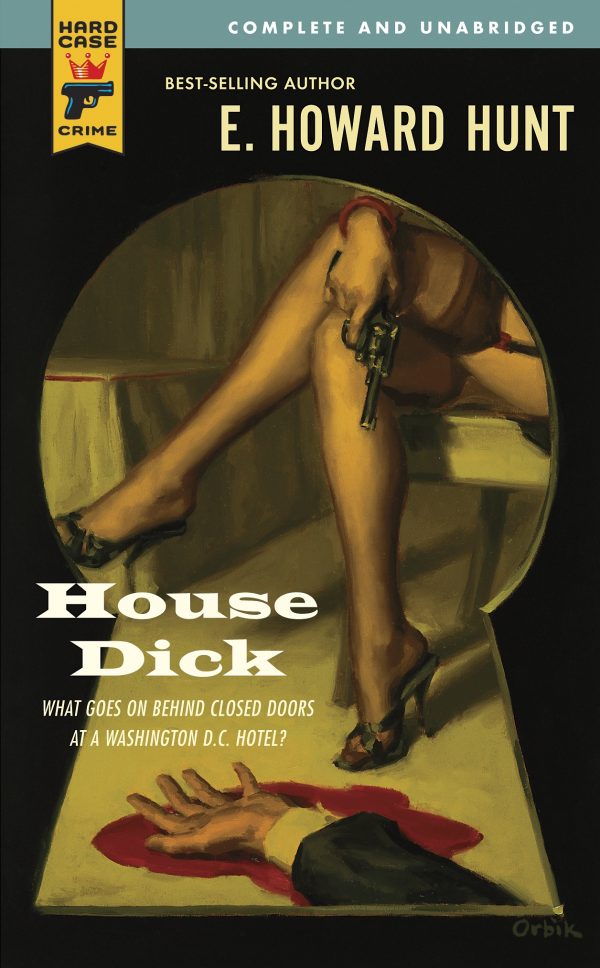

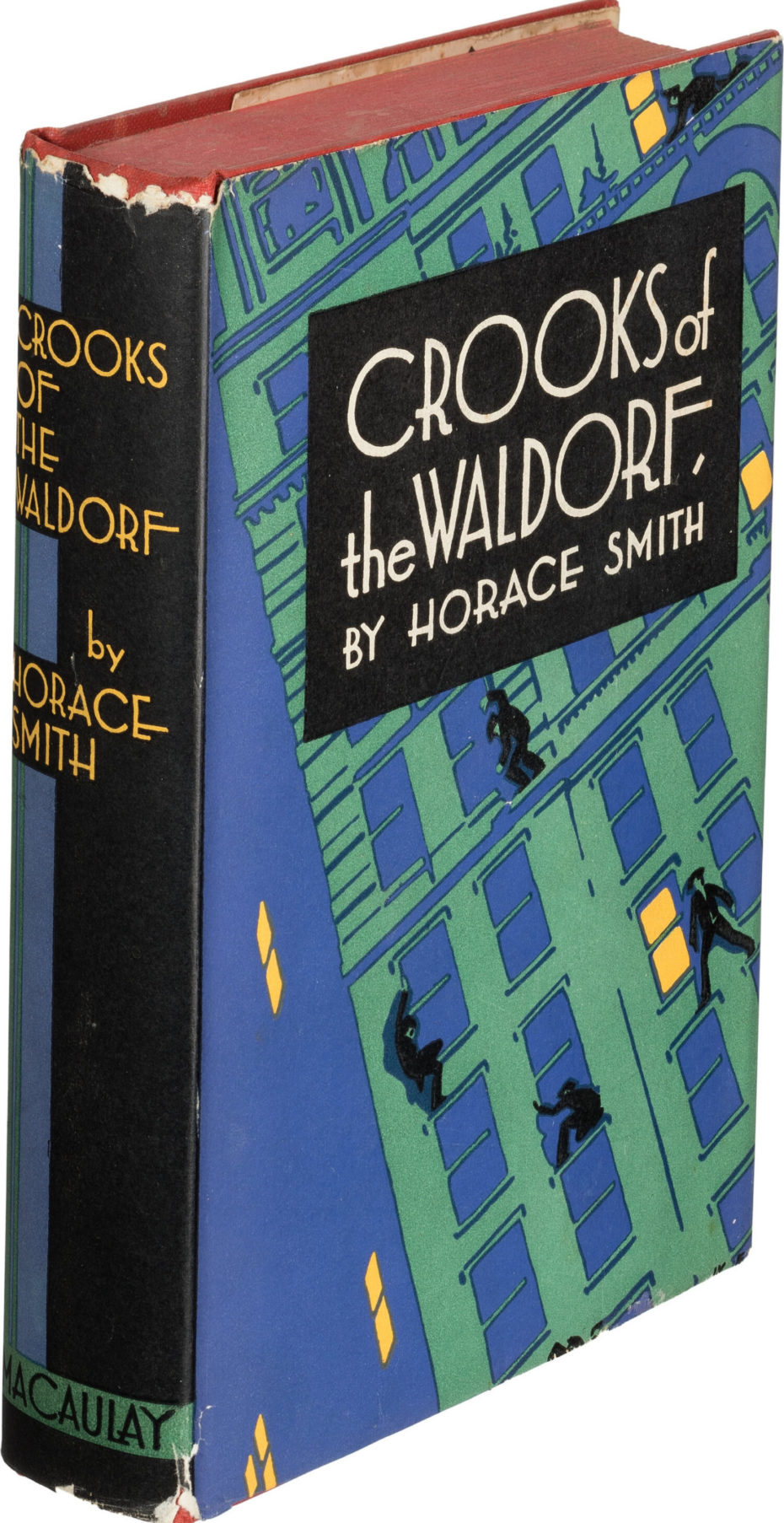

Top man at the Waldorf-Astoria during Prohibition was master hotel detective, Joe Smith, whose feats of deduction were so legendary they were complied in a book, “Crooks of the Waldorf” by Horace Smith, published in 1929. The Waldorf-Astoria may have been one of Manhattan’s most prestigious hotels, but chapter titles like ‘The Female Prowler’, ‘The Hotel Annex – A Traveling Speakeasy’, and ‘The Come-On Girl’ give an alternative insight into the sort of behaviour Joe Smith tried to stamped out to protect the glamorous hotel’s reputation: “The Waldorf was his church and any violation of its sanctity was a desecration”, claimed his biographer.

“Unless you were looking for Joe Smith you would never pick him out as the Chief Detective. If you noticed him at all you would probably regard him as a guest from out of town; perhaps a successful business man from some western city. But you can be very sure he would see you, and look you over in one swift appraising glance that told him all he wanted to know about you.”

Operating out of the limelight in a business where discretion was as important as catching the criminal was paramount; the reputation of the hotel meant criminal elements had to be swiftly and quietly secreted out of the hotel with the minimum of disruption. One of the main problems wasn’t as much prostitution but theft: according to house man Joe Smith, “the woman who comes in and sits around the lobby waiting to be picked up by some flirtatious but innocent and confiding guest who will give her a chance to rob him.”

“The way they dress nowadays with short skirts and rouge and lipstick and plucked eyebrows, it is almost impossible to tell a good woman from a bad one. They are as cunning as rats….they generally come in late in the afternoon through one of the 33rd Street entrances on the opposite side of the hotel from the office. In that way they figure they are less likely to come under our immediate attention…the smartest of them will take an elevator to create the impression they are staying in the hotel. They are always expensively and often stunningly dressed with a display of jewels that is never out of form. It is through their persistence in coming back that we land them. It isn’t good business to have men going around the country telling how they were robbed by a woman they picked up in the Waldorf lobby.”

But often prostitution and theft went hand in hand: male guests who’d been robbed by a working girl would rarely admit to the management that they’d brought her up to their room, instead claiming they’d been robbed by a maid. Back at the Adolphus in Dallas, Charlie Coyle had a simple method to deal with such guests, “If a guest comes down in the morning and says his wallet was stolen, the first thing I do is look up my hooker reports to see if he had a girl up there. The guest is trying to say that the hotel is responsible for the loss. You ought to see the expression on some of their faces when I say, ‘But what about the girl you took up to your room at twelve-eleven last night?'”

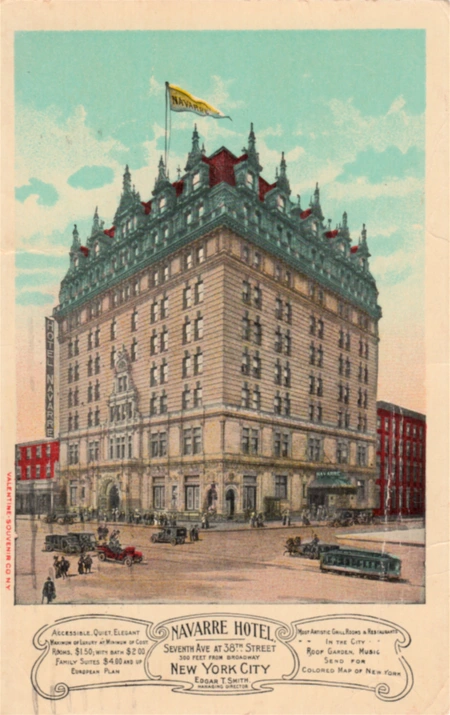

But as well as the endless revolving door of guests checking in and out, a good hotel detective also kept a keen eye on the staff. In 1902 at the Hotel Navarre on 7th and 38th in midtown Manhattan, house man Maxwell noticed one hotel cashier was spending a lot of money and living the high life. His investigations showed he’d been fiddling the books. Rather than make a scene inside the hotel, Maxwell followed the cashier to Coney Island where as the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported, “he’d gone in the company of two women said to be chorus girls,” where Maxwell turned the villain over to the police. A spate of thefts at a large hotel on Broadway, back when Times Square was still called Long Acre Square, saw the house man discharge one chef, three cooks, two porters, half a dozen chambermaids and a woman in charge of the linen room. The robberies promptly stopped. (From the New York Times, June 1902, ‘Hotel Detectives and their Experiences.’)

While the house detective might have had some easier days tracking down lost property, the workday could swiftly turn violent. In the summer of 1883, the house man at Coney Island’s Hotel Brighton was talking to a porter at 10pm on the main staircase leading to the hotel entrance, when after a busy night, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported, “A party of rather rough looking men were ascending the hotel steps, and evidently intoxicated. They were about a dozen in number and most of them pretty hard looking customers. The leader of the gang applied a vile epithet to Inspector Folk, and another member of the party struck Mr Folk a stunning blow, knocking him down the entire flight of steps. Folk was on his feet in a moment, however, and rushed in amongst the roughs, dealing blows right and left with a cane he held in his right hand.”

James Gerrity at the Hotel Edison, with whom we started our tale, was far less fortunate: Saverio Bongiorno in room 1135 simply shot him dead in the hallway.

For the large part, the working life of a hotel detective was mostly routine and conducted at night, constantly patrolling the quiet corridors of the hotel whilst keeping an eye out for the unusual. “I like this work,” explained Charlie Coyle at the Adolphus. “And I like trying to keep some of these silly people from getting rolled.”

For better or worse, modern technology has made the traditional hotel detective obsolete. Security cameras, miniature safes and changes in moral ethics means the personal touch of having a full time detective to protect guests and the good name of the hotel is a thing of the past. But we like to think of our world weary hero still taking up his position in a discrete corner of the lobby, keeping a watchful eye on the main entrance to the hotel whilst all the guests lie asleep in their beds.

Take a trip back in time to the 1920s with an audio series of hotel detective stories from CBS radio here.