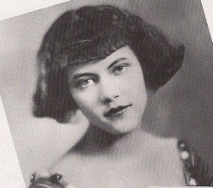

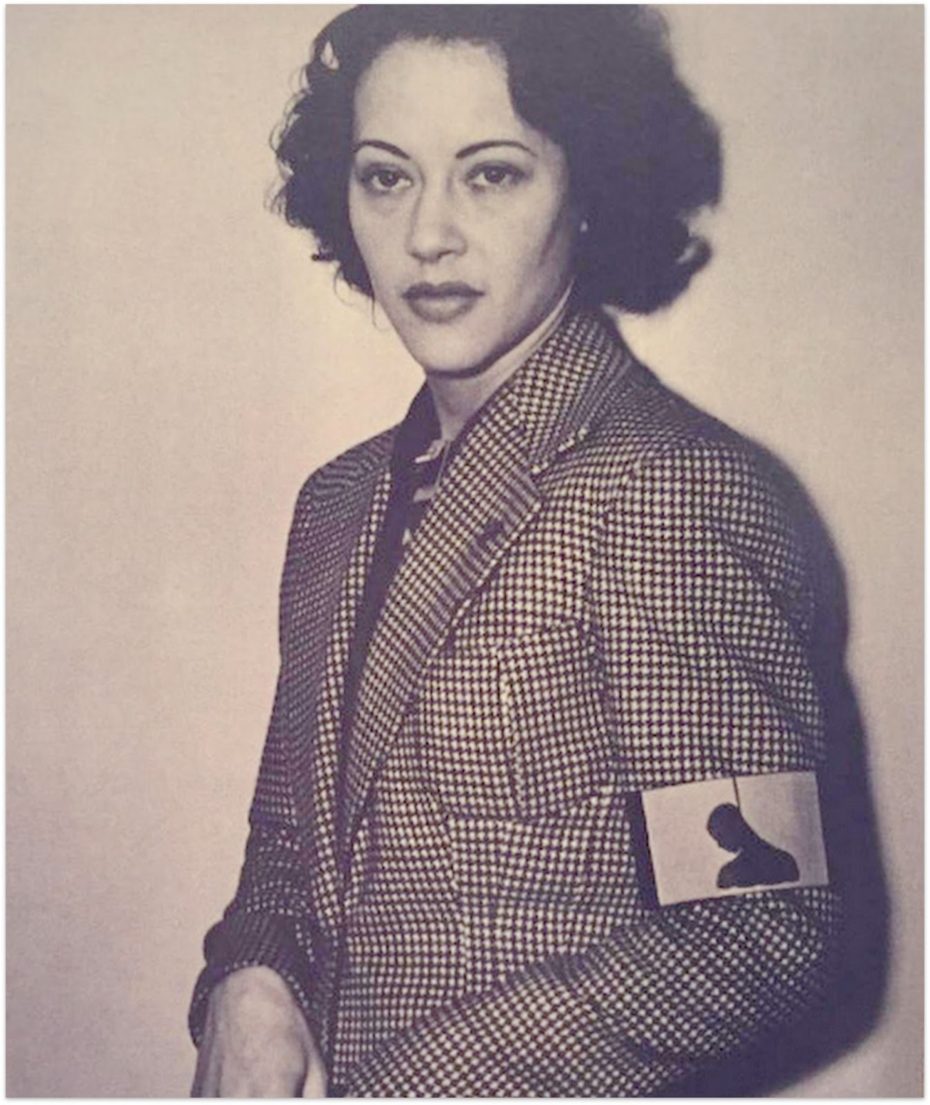

In 1934, a young woman stepped off the train in Los Angeles’ Union Station. Even in a city swarming with beauties, eyes would’ve fastened on her. She was astonishingly lovely — tall and lithe, with dark glossy hair she wore pulled back in a style that offset her porcelain skin and blue eyes. Everyone who saw her that day thought she was white. She wasn’t. They’d think she was just another aspiring starlet. She wasn’t that either. Her name was Fredi Washington and she descended on Hollywood with a burning mission: to redefine white America’s image of African American women.

Born Fredricka Carolyn Washington in Savannah, Georgia, she was the daughter of a postal worker and former dancer and the eldest of nine children. Everyone called her Fredi. By the time she was sixteen, New York beckoned. These were the early years of the Harlem Renaissance, when an electrifying energy emanated from the neighbourhood’s theatres, restaurants, churches, beauty parlors; when ragtime, blues, and jazz boomed from its countless dancehalls, bars, and music halls; when the arts, in every form, were being reimagined and revived by Harlemites.

In 1921 word got around Harlem that a new all-black production was hiring dancers…

“It wasn’t that I wanted to get into show business,” she’d reflect years later. “But somebody told me they were paying more to chorus girls than I was making as a bookkeeper.”

She’d never danced on stage — hadn’t even set foot in a theatre, but she slapped on some lipstick (another first) and with that she threw herself in with the other hopefuls.

The show was Shuffe Along, the first Broadway show created, produced, and performed by African Americans. Washington was hired as one of the “Happy Honeysuckles,” earning a wage of $30 a week—twice what she’d been making as a bookkeeper.

The eleven “honeys” were chosen as much for their fair complexions as their dancing chops and singing talent. It was understood that only women who passed the “brown paper bag test” got hired. The odious practice was used openly during castings until the 1950s, as well as amongst upper class Black American societies such as sororities, fraternities, even churches. Only those with a skin colour that matched or was lighter than a brown paper bag would be allowed admission, membership privileges, or get hired for certain jobs.

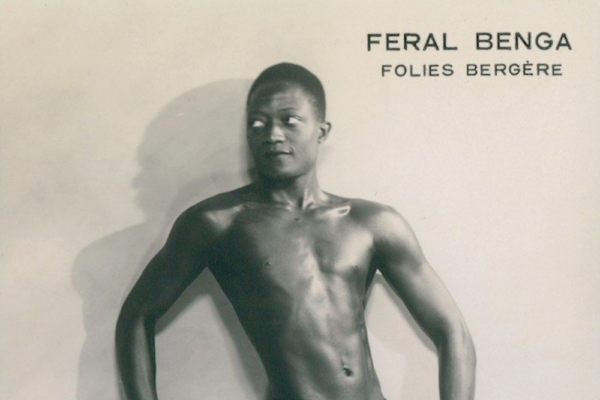

A girl named Josephine Baker had passed the test – but only just. The darker-complexioned Baker was teased and tormented by the other chorines. During one especially cruel episode, Washington stood up for her. They became lifelong friends.

Shuffle Along was a huge hit. After its New York run, the show toured for three years and was the first Black musical to play in white theatres across the United States, creating a rare bridge in the country’s toxic racial divide.

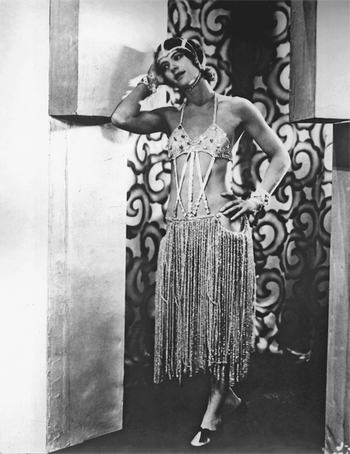

When the show closed for good, Washington went on to perform at the swanky Club Alabam’, which, like Harlem’s infamous Cotton Club, featured Black performers but catered exclusively to wealthy white patrons. Here, a besotted Wall Street millionaire urged her to assume a French name, offering to pay her tuition at the prestigious Theatre Guild School if she agreed to pass as French.

“But I want to be who I am,” she told him, refusing his offer, “nothing else.”

She performed on New York stages all through the 1920s, but with scant roles available to her, she eventually hightailed it to Europe, where for two years, she headlined a ballroom dance team of Fredi et Moiret. Washington and her partner performed in Paris, Nice, Berlin, Dresden and Hamburg. In London she taught the Prince of Wales the “Black Bottom,” the latest dance craze to have jumped over the pond.

Like her friend Josephine Baker (who by then had Paris in the palm of her hand), Washington discovered that Europe offered a far freer atmosphere for African Americans. Unlike Baker, she chose to return to America.

“Director requires in the leading role, a young girl who must be of Negro blood but must be absolutely white.”

This was the Hollywood casting call that went out for Imitation of Life. Adapted from a popular 1933 novel by Fanny Hurst, it’s the story of two mothers, one white, one Black, who meet and become friends and then business partners. The most dramatic storyline centres on Peola, the light-skinned daughter of the Black mother, who crosses the colour line — with tragic results.

In a departure from what was then the standard practice of hiring white actors to play Black characters, the film’s director, John Strahl, was keen to find a “White Negro” for the role of Peola, a woman “so white that not even her own lover would realize the secret of her birth.” He travelled the country and considered over three hundred actresses. When Stahl saw Fredi Washington on a New York stage, he knew he’d found his Peola.

No sooner had negotiations started than Washington insisted on being paid what she was worth — a revolutionary notion in Hollywood. She also refused to sign a four-year contract, reasoning that after Imitation of Life, the studio would have stuck her in roles she had no interest in playing.

“Look,” she told John Stahl. “I didn’t come here to learn to act. I brought that with me. I’ve been on Broadway. You don’t have to sell me a bill of goods, because you can’t. Because I’m really not that interested. It doesn’t matter to me whether I make this picture of whether I don’t, because I know one thing — if I make it and I’m good, you’re not going to have another script for me so I wouldn’t want to be thrown in a western here or this-or-that there.”

Imitation of Life was a runaway box office hit. As one of the first films to suggest, if even only obliquely, that America had a “race problem,” it hit a nerve with both white and Black communities. The film garnered three Academy Award nominations.

White audiences tended to conflate Washington with the character of Peola, assuming she herself endorsed and even practiced passing. But she’d never identified as anything other than Black. The “tragic mulatto” trope (a person one Black parent) suggested self-loathing, isolation, and exile, but Washington played the role with a nuance that seemed lost on many people. Black audiences, meanwhile, tended to interpret the film as Washington herself did: the rebellion of a Black woman trying to gain the privileges only given to white people.

“How many people do you think there are in this country who do not have mixed blood?” she asked one reporter. “There’s very few if any, what makes us who we are, are our culture and experience. No matter how white I look, on the inside I feel Black. There are many whites who are mixed blood, but still go by white, why such a big deal if I go as Negro, because people can’t believe that I am proud to be a Negro and not white. To prove I don’t buy white superiority, I chose to be a Negro.”

In the end Hollywood didn’t know what to do with her. With her sleek sophistication, producers wouldn’t cast her as a Black a maid, but neither would they cast her in any of the roles on offer for white actresses. She’d be told many times that her refusal to pass came at a price. She could’ve been as big as the biggest stars of the period, Joan Crawford and Greta Garbo, maybe bigger.

“Why should I have to pass for anything but an artist?” she demanded.

After Imitation of Life, she stayed in Hollywood because she thought she might play a role in changing how the film industry, and therefore America, saw African Americans. Like other early Black performers, she carried a mantel for her race at what must have often been a personal toll. Like Dorothy Dandridge and Lena Horne, two light-skinned actresses who’d come up in the forties and fifties, she’d be forced to darken her skin. Even then, her roles were confined to tragic mulattoes or exotic temptresses.

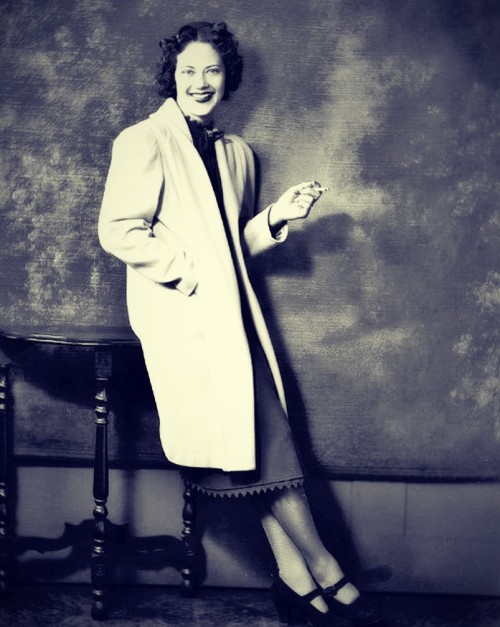

After five years she was done with thin scripts and jezebel roles and silly plots; she was sick of tolerating poor treatment and waiting for roles that never materialized. She returned to New York where, in 1937, she co-founded the Negro Actors Guild of America and worked with the NAACP. She criticised the treatment of African Americans in the entertainment business, such as the requirement that they enter the stage from a back door or put up with shoddy living quarters when touring.

In 1943, she joined the staff of the People’s Voice. Founded by future Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr., People’s Voice set a standard for Black journalism. Initially Washington worked on its public relations team, but soon she began filling in for columnists. Eventually she got her own column, writing over 200 pieces of drama, film, and media criticism.

Her pieces for the magazine are smart and sometimes unsparing in their honesty; her writerly voice is vivid and bold. She also took on broader social issues, as when she criticised the treatment of Black soldiers during and after World War II. At the end of every piece, she’d sign off with her trademark call to action.

When she returned to Hollywood in the 1950s, it was in an entirely new capacity. She worked as a casting consultant for the breakthrough films, including Carmen Jones and Porgy and Bess. A realist as well as a fighter, she understood the industry might never fully address its race problem. In the meantime, and until her death in 1994, she threw herself into the new roles she created for herself — advocate and activist.