Imagine gathering around a dinner table with the guy who stole the Mona Lisa, an heiress who stole a Vermeer, the “gentleman thief” responsible for some of the most sensational art thefts in Europe, and let’s throw an invite to Pablo Picasso for good measure, for his own attitude towards the world of art fraud is seriously questionable. Keep the wine pouring and imagine the conversation! We’ve put together a guest list for a most surreal dinner party – just remember to hide the good china.

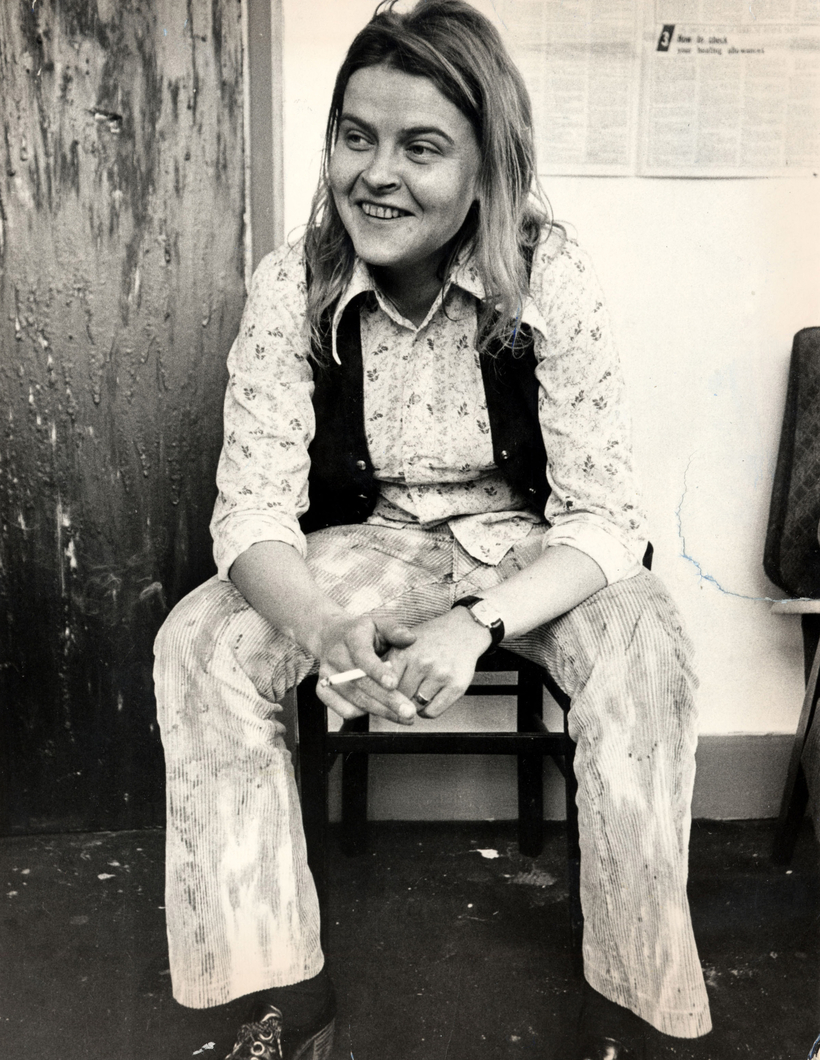

Rose Dugdale

Arguably more of an activist than a klepto, Rose Dugdale is the British heiress who will nevertheless go down in history as one of the only major female art thieves of note. The London debutante who stole a Vermeer rebelled against her posh upbringing by joining the IRA in the late 1960s after becoming radicalised by the 1968 student protests (and a trip to Cuba). She gave away much of her inheritance to the poor and was involved in the Civil Rights movement, but set her sights on Irish independence became a member of an active service unit that took part in helicopter attacks. In 1974, she helped raid the house of a British Conservative Party politician and stole 19 old masters by the likes of Thomas Gainsborough, Francisco Goya and Peter Paul Ruben. The most famous of the loot was Vermeer’s “Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid.” They left a ransom note demanding money and the release of IRA prisoners, but were apprehended. Dugdale was sentenced to nine years in prison, becoming half of the first couple to ever get married while incarcerated in the Republic of Ireland and also giving birth while detained. She has continued to advocate for Irish independence, but through the less illegal realm of politics.

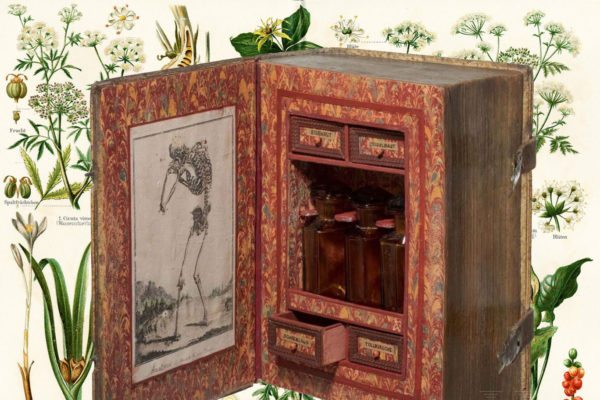

Stephane Breitwieser

Between 1995 and 2001, French art thief Stephane Breitwieser pilfered 1.4 billion dollars worth of art, some 239 pieces of art from 172 museums around Europe while traveling the continent working as a waiter. This works out to a theft about every 15 days, so it’s no surprise the Guardian called him “arguably the world’s most consistent art thief.” He focused largely on regional museums with more relaxed security. What set Breitwieser apart from most thieves was that he did not steal for profit; he was an art lover and connoisseur, particularly of 16th and 17th century masterpieces and hung many in his own bedroom. He never sold any of the art he stole. However, his mother destroyed close to 100 pieces (kept for safekeeping) to get rid of evidence. Breitwieser was finally caught in 2001 when attempting to nab a 16th-century bugle from the Richard Wagner Museum in Lucerne, Switzerland. He served a three-year sentence and published a memoir in 2006 called Confessions d’un Voleur d’art (“Confessions of an Art Thief”). Although it doesn’t seem like Breitwieser totally left his life of crime behind; he’s been arrested multiple times in the years since, and further house raids have revealed more stolen objects in his residence. Hollywood was set on making a movie about Stephane’s escapades, but we’re still waiting.

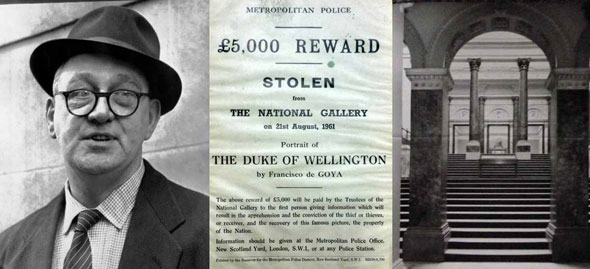

Kempton Bunton

Sometimes art robbers are motivated by revenge. Kempton Bunton was a disabled retired bus driver who was frustrated about having to pay the television licensing fee out of his own modest income. His anger reached a boiling point in 1961 when he learned the British government was willing to pay millions of pounds (in today’s money) to keep Francisco Goya’s “Portrait of the Duke of Wellington” on British soil. Supposedly based on intelligence from National Gallery guards, Bunton was able to get past the electronic security system and escape through a bathroom window with the portrait. In a letter he sent to Reuters, he demanded amnesty and £140,000 to pay for poor people’s television licenses. His request was declined. In 1965, he returned the painting anonymously and a few weeks later surrendered himself to police. He was eventually found guilty not of stealing the painting but just the frame, as it had not been given back. The unconventional thief — who had initially been disregarded as a suspect because of the improbability of him being able to commit such a heist — inspired popular culture; the crime was referenced in the 1962 James Bond film “Dr. No” and is the subject of the 2020 film “The Duke.”

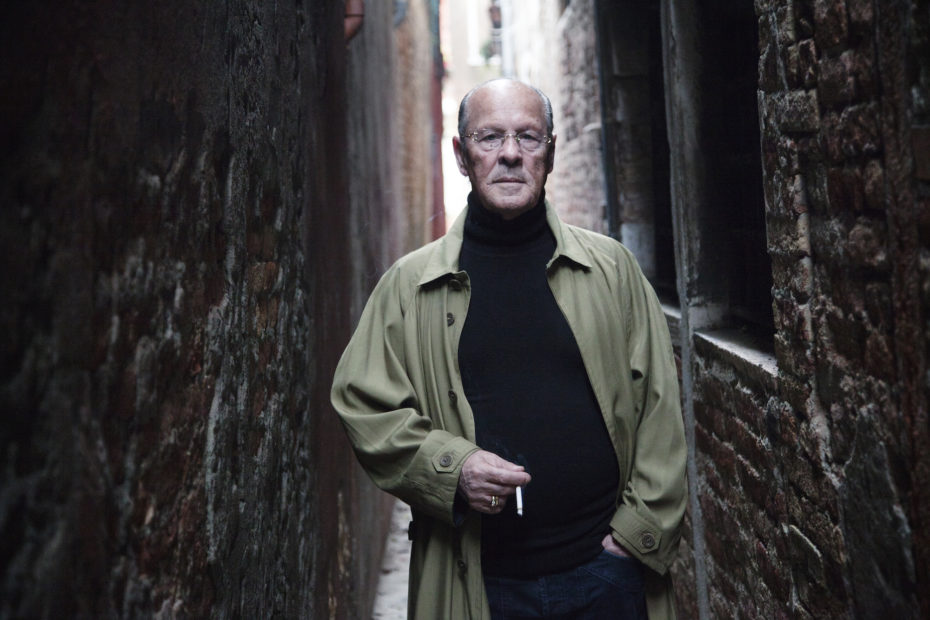

Vincenzo Pipino

The “gentleman thief” of this gathering, Vincenzo Pipino is the first person to successfully steal from the Doge’s Palace and has committed over 3,000 thefts at museums, galleries, banks and homes during his life. Pipino — who has drawn connections to the fictional French gentleman thief Arsène Lupin — supposedly began stealing at 8 years old while working as an errand boy. Because of his fear of the dark, Pipino committed his crimes during the day, targeting the grand residences around Venice’s Grand Canal and the Piazza San Marco. Pipino was an accomplished climber and kept a code of conduct not unlike a modern-day Robin Hood, only stealing from the rich and also offering ransoms so items could be returned. One of his most notable heists was the 1991 theft of the “Madonna col bambino” from the Doge’s Palace, the former residence of the Doge of Venice, now a very famous museum. More in it for the notoriety that financial gain, Pipino quickly returned the painting. His actions (which also included the less gentleman-like activities of drug trafficking and credit card fraud) resulted in 300 police complaints and 15 sentences equaling over 25 years in prison, which he served in Italy, Germany, France and Switzerland. Pipino has published two autobiographies, and although retired, still says he is destined to die while incarcerated.

Bruno Lohse

The true villain who begrudgingly finds his seat at our table is Bruno Lohse, a German art dealer and SS-Hauptsturmführer who, during World War II, helped Hermann Göring become the largest private art collection in Europe. An art dealer by profession, Lohse was the chief art looter in Paris during the Occupation. Lohse came to Paris in 1940 to catalog the expansive collection of French-Jewish art dealer Alphonse Kann. Sadly, Kann only recovered a small part of his works before his death. Between 1942 and 1944, Lohse supervised the theft of at least 22,000 art objects in France, setting aside the most valuable for Göring and Hitler’s planned Führer Museum. After the German surrender, Lohse avoided a lofty prison sentence through collaborating with authorities (though potentially giving false information) at the Nuremberg trials. While he was technically prohibited from continuing to work as an art dealer, he still amassed a collection of old masters and Expressionist paintings supposedly valued in the millions after the war.

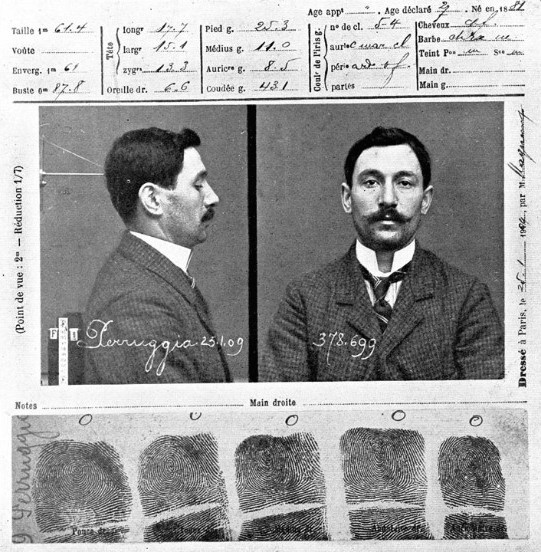

Vincenzo Perrugia

One of the most impressive art crimes in history was done by an insider, Vincenzo Perrugia, an Italian museum worker who stole the “Mona Lisa” in 1911. Peruggia swiped the renowned painting after spending the night in a broom closet and left the museum with it hidden in his coat. The looting of one of the world’s most famous — and valuable — artworks became a real whodunnit to determine the culprit. Their first suspect was Guillaume Apollinaire, an avant-garde poet, art critic and co-creator of Cubism whose hatred for the Louvre was well-known across Parisian society. During questioning, he pointed the finger at none other than Pablo Picasso (who may not have been entirely innocent) who was then hauled into open court for intense interrogation by the judge. Apollinaire and Picasso were later both set free. The importance of the case resulted in the Louvre being closed for a week, museum administrators losing jobs and French borders closing as every ship and train was searched. A reward of 25,000 francs was announced.

After two years. Perrugia was finally caught when he tried to organise a sale of the missing Mona Lisa to the directors of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. He was an Italian patriot and believed the “Mona Lisa” was a symbol of Italy that should have been returned to its homeland. Peruggia was hailed for his patriotism in Italy and served seven months in jail.

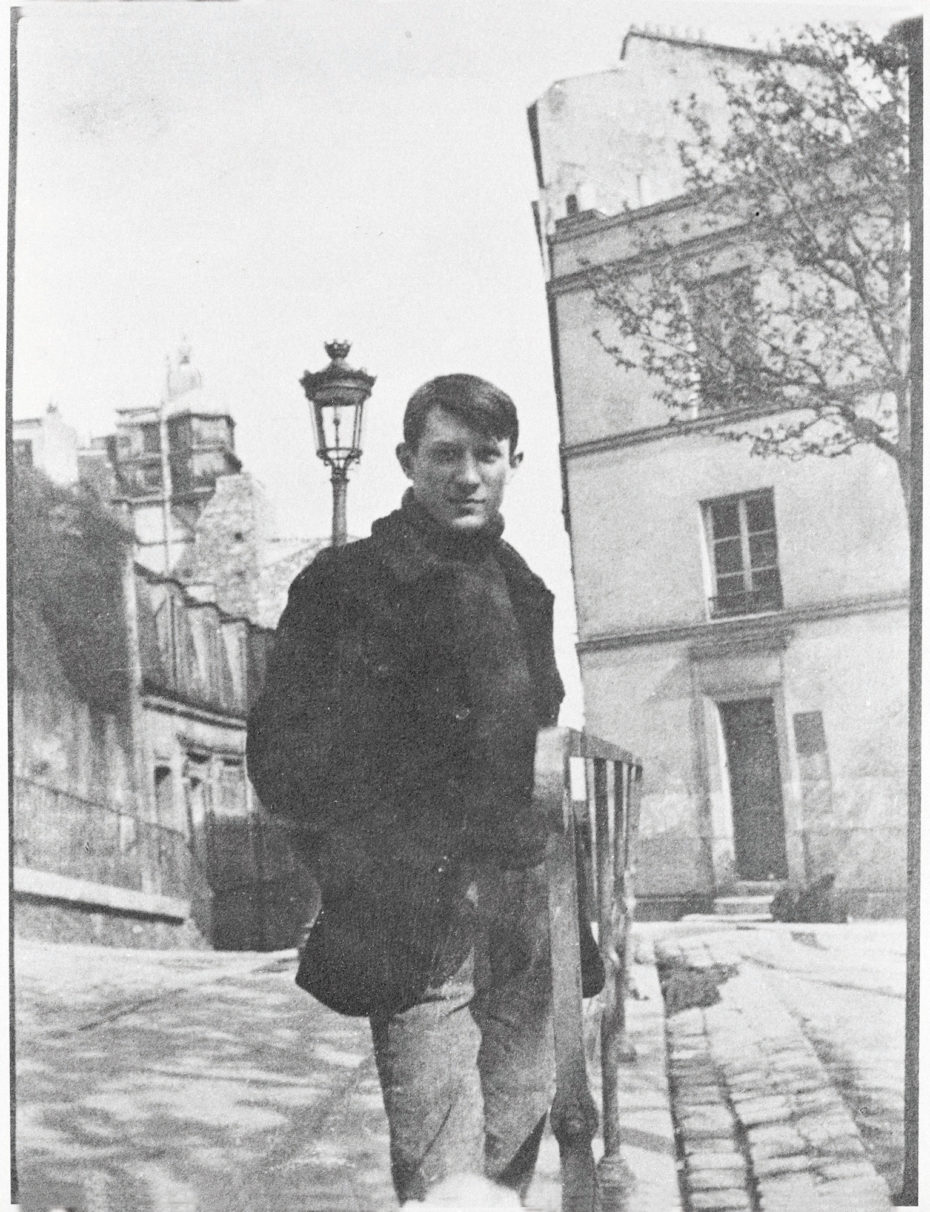

Picasso

But back to Pablo. The Cubist painter was indeed in possession of something stolen from the Louvre. In 1907, Picasso, bought a pair of 3rd-century BC Iberian statue heads that Belgian art thief Joseph Gery Pieret had taken from the Paris museum. It’s still unknown if Picasso had commissioned the theft. The artist was fascinated by the history of the Iberian people who lived in his Spanish homeland a millennia ago. He told his so-called friend Apollinaire that he wished to uncover the secrets of their “ancient and barbarian art.” Picasso kept the heads hidden in his sock drawer, but didn’t totally hide his bounty. The statues were an inspiration for his 1907 painting, “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” the artwork that launched Modernism.

If you’re interested in learning more, the Association for Research into Crimes against Art (ARCA) provides a postgraduate certificate program that specialises in the study of art crime and cultural property protection – surely the ultimate conversation starter for the ideal dinner party.