The passage up the Blue Nile has always been both a physical experience and an allegorical tale. Thousands of years after pharaohs were ferried to the afterlife on golden barges, the steamboat began transporting mesmerised 19th century tourists past their temples in search of something otherworldly. This graceful journey up the river, passing ancient pyramids and crumbling burial sites was the subject of legend, captured in books and films over the past 150 years. Agatha’s Christie’s novel Death on the Nile (1937) perhaps encapsulated all the mystery, glamour and intrigue of this river’s colossal history in one moment, exotically intertwining the ancient Egyptian’s fixation on death, dusty ruins, luxury steamships and ill-gotten wealth with a contemporary death plot.

Egypt in the 1930s was a busy place. The interwar years had seen stability and most of all, global interest in antiquity following archaeologist Howard Carter’s unearthing of Tutankhamun’s Tomb in 1922. While not all went to Egypt armed with shovels and spades, the find had awakened a world interest. Agatha however, was no rookie when she accompanied her second husband, the renowned archaeologist Max Mallowan, on a steamboat trip up the Nile on the SS Sudan.

Christie had previously spent time in Egypt in 1907, when her mother had moved there for the warmer winter weather and the ease of living away from damp and expensive England. In fact, Agatha Christie’s first novel Snow upon the Desert was based on her experiences at the Gezirah Hotel in Cairo. She’d met Max in 1930, at a dig site in 1930 when Christie was travelling solo through Mesopotamia (now in Iraq) looking for her next story. Just like her train-ride to Baghdad on the Orient Express would inspire the novel Murder on the Orient Express in 1934, her journey down the river aboard the SS Sudan would inspire Death on the Nile in 1937.

Archaeology was not yet the science it is today in Agatha Christie’s day. It was still very much an amateur’s treasure hunt, and an expensive one at that. Agatha’s witnessing of the excavations with her husband gave her an insider’s view of the archaeological process, which let her describe both the digging and the monuments in painstakingly true detail. The essence of the novel, like the meticulous and often unpredictable process of archaeological excavation, is about the slow unearthing of clues, the assemblage of broken parts and the discarding of an abundance of ‘red herrings,’ all culminating in a shock ending. Both books brought further fame to these already popular luxury escapades. The irresistible combination of wealth, grandeur, greed and the promise of adventure thrilled the modern interwar public who now felt compelled to go up the Nile.

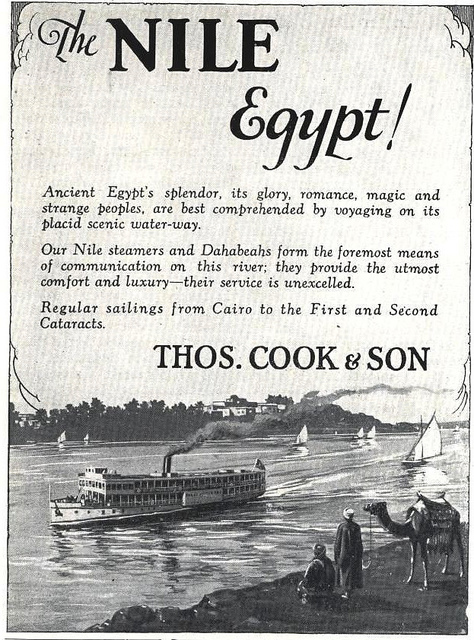

Thomas Cook had founded the first escorted travel business in England in 1841 and Egypt would become the first popular “exotic” travel destination outside mainland Europe’s boundaries. By the late 19th century, Ancient Egypt was a firmly established ‘must-visit’ for those of means. Despite the heat, sand and general unsavoury conditions for ladies of high society, the trip had also attracted many women adventurers such as Florence Nightingale who resided in and wrote about Egypt in 1850. She vividly described her intoxication with Cairo, “The Rose of Cities” and sailed up-river to Abu Simbel in a local Dahabiya, one of the old traditional boats.

In the early 19th century, these were the only vessels available for hire. They were unpredictable, usually had a rat problem, lacked maintenance and often came captains of dubious reputation. In order to prepare one’s trip, Gardner Wilkinson’s Handbook for Travellers in Egypt (1847) warned of rogue captains and rotten ships and suggested passengers bring their own bedsteads, carpets, rat-traps, washing tubs, guns and tea. Pianos and chickens were also on the travel-accessories list. It could take a traveller as long as three months to sail from Cairo to Aswan and back while hugging the banks and travelling at a snail’s pace.

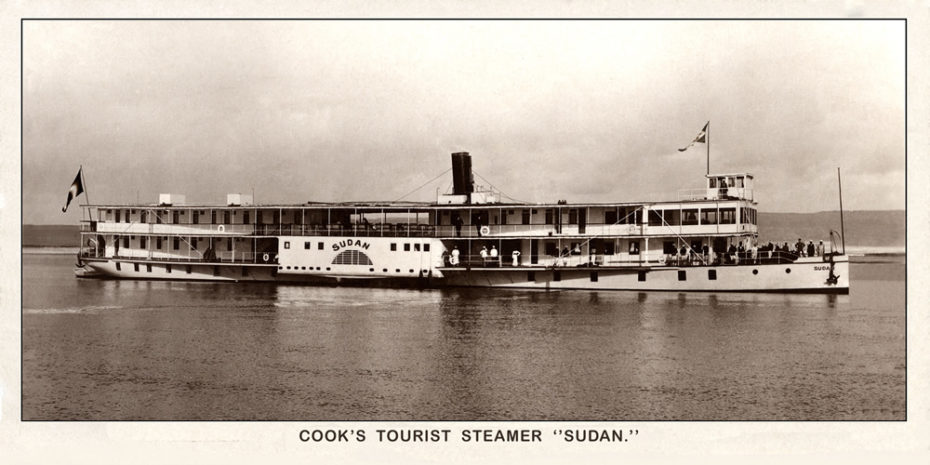

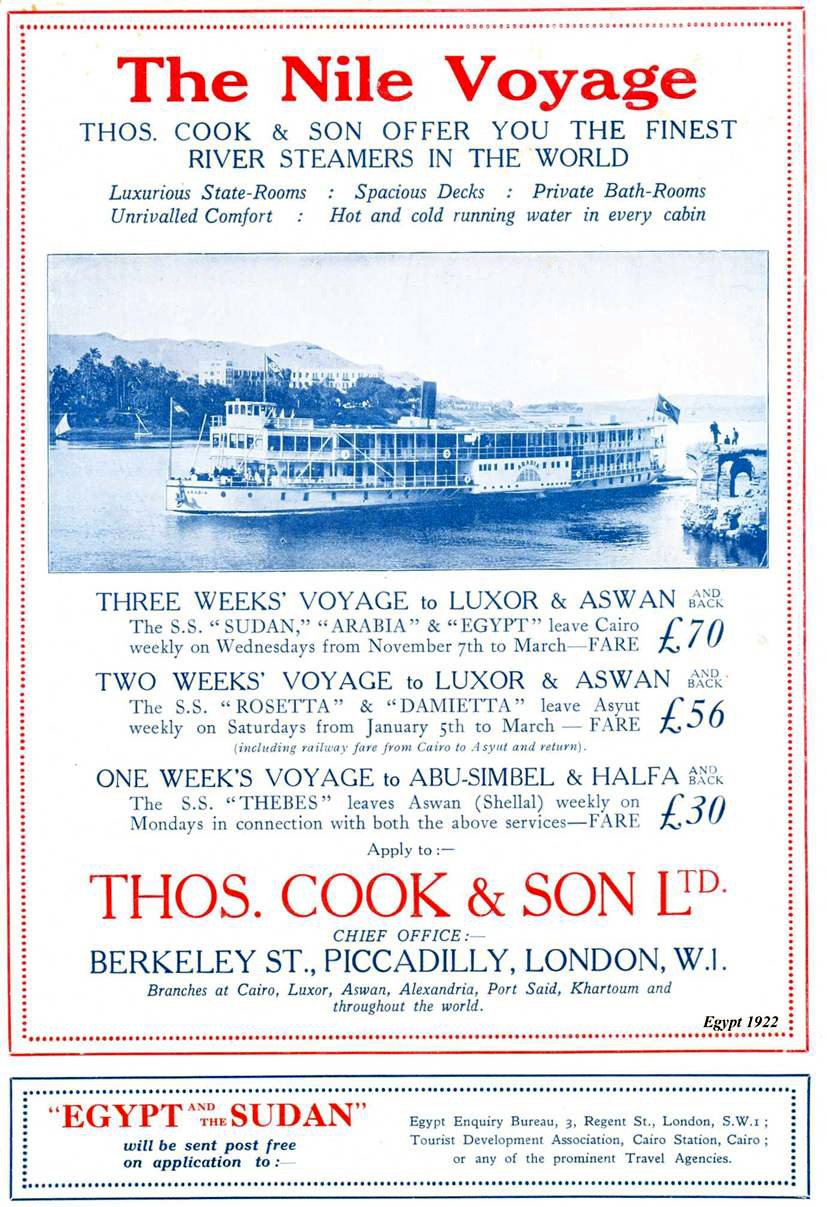

The steam-driven ship, however, would prove to be the future Rolls Royce of the mighty Nile. In 1911 Thomas Cook commissioned a fleet of new, luxurious and faster steamboats that could now make the journey from Cairo to Aswan in twenty days, one of which was the SS Sudan. It was said of Cook’s commercial escorted travel services in Egypt, “By the turn of the century, there were two empires on the Nile – Britain’s military occupation, and Cook’s Egyptian travel”.

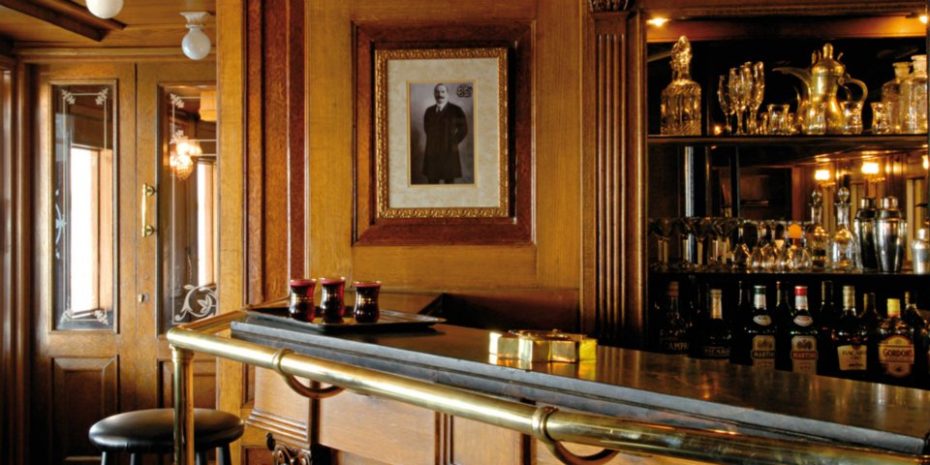

The steamboat SS Sudan, like Cook’s earlier vessels, was built at Scotland in 1915. She was 236 feet long and displaced 600 tons. With a simple layout of two stacked matching decks of veranda-lined luxury cabins and lavish suites all looking outward and designed to take eighty passengers, the SS Sudan was elegant and luxurious, sporting her boilers below and a tiny wheelhouse on top. Cook’s advertisement boasted luxe “private bathrooms with hot and cold running water in each cabin.”

The layout of the SS Sudan has changed little since Cook’s time and today she offers five suites and eighteen cabins. The cabins are named after famous characters who had travelled the Nile in the past. An upper deck prow cabin where Agatha Christie stayed is suitably named after her. The neighbouring cabin once belonged to Lady Duff Gordon, a high society author who settled in Luxor after contracting tuberculosis, best known for her Letters from Egypt. Howard Carter, the archaeologist who discovered Tutankhamun’s tomb and King Farouk, the penultimate king of Egypt, are amongst others lending their names to the sumptuous panelled and gilded rooms. The golden age of Nile cruising lasted from 1922 – 1935, serving powerful politicians, well-to-do archaeologists and ever-increasing tourist numbers.

The year 1936 saw the accession of King Farouk, a much loved national figure at the time, to the Egyptian throne. Unfortunately he was unable to reform and modernise Egypt, something that was increasingly demanded by the public. World War II erupted, tourism on the Nile ceased, the desert war between Britain and Germany began and Agatha Christie returned to Britain. The post-war world was new, social change was gathering pace across the globe, regional conflict was flaring up in the Middle East and all this discouraged a return of tourism to Egypt for decades to come. As British colonial influence ended, so followed Cook’s Egyptian Tourism operation. The steamship SS Sudan had been docked for the war and was to be abandoned for the next 50 years with the Cold War’s political instability crippling Egypt.

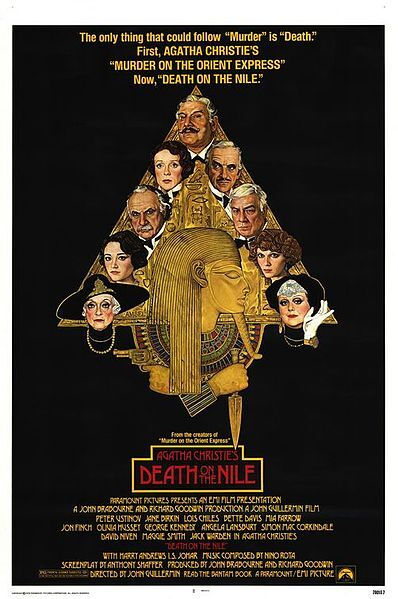

A new dawn opened with the touring exhibition, ‘The Treasures of Tutankhamun’ in the 1970s and saw the rebirth of global interest in ancient Egypt. In 1978, the first movie version of Death on the Nile brought about a sudden nostalgia for the lost world of luxury pre-war cruises. Egypt’s post-monarchic government’s allegiance to the Soviet Union waned as it then looked westwards once again. The steamship SS Sudan was to be rescued. The first attempt to relaunch her as a touring boat by a German tour company in 1999 failed. The SS Sudan soon thereafter made a cameo appearance as the Karnak in the second version of the film Death on the Nile in 2004. Finally in 2006 the French tour company Voyageurs du Monde did what was always required and completely restored the SS Sudan to her former glory, keeping the historic layout but providing her with modern engineering and services.

Now the last steamship on the Nile, one of the oldest still operating in the world, the SS Sudan is a national, if not a world treasure. She is dry-docked every 4 years for refits and repairs to her hull, engines, dining room, kitchen and cabins. She now boasts of being supplied from her own vast, organic, Nile-side kitchen garden. This is befitting, as her predecessors, the glittering gilded barges of the Pharaohs also cruised the Nile, collecting provisions from their lush riverside plantations. And like the immortality of the Pharaohs, the SS Sudan lives again both on the river today and under the nom de plume Karnak in the new and third film version of Death on the Nile in cinemas this February 2022.