What do you love most about Paris? Perhaps it’s looking up at all the limestone detail of Haussmann’s grand boulevards or getting lost down a cobblestone street leading to a hidden bucolic courtyard. Those classic grey zinc roofs that provide the perfect reflection for the city’s famed sunsets aren’t bad either. Or maybe it’s just the simple pleasure of sipping un café en terrasse and taking it all in. These moments seem all the more sacred when you find out the Paris of today with all its quintessential quirks almost became a thing of the past after a dangerously close shave with a wrecking ball in the 1920s. If successful, the Seine would now be surrounded by a sea of skyscrapers. Quelle horreur! Let’s go back to the drawing board with the controversial architect, Le Corbusier, to see what could have been for our beloved French capital…

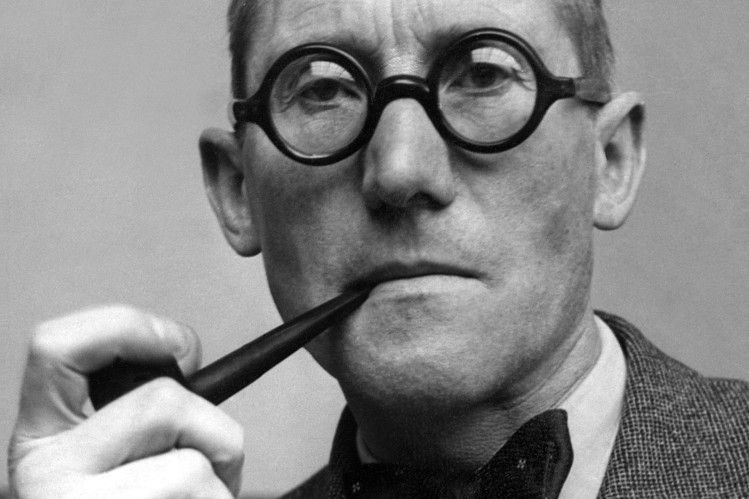

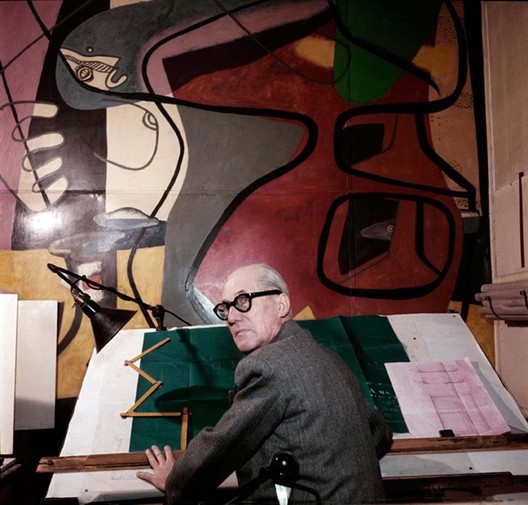

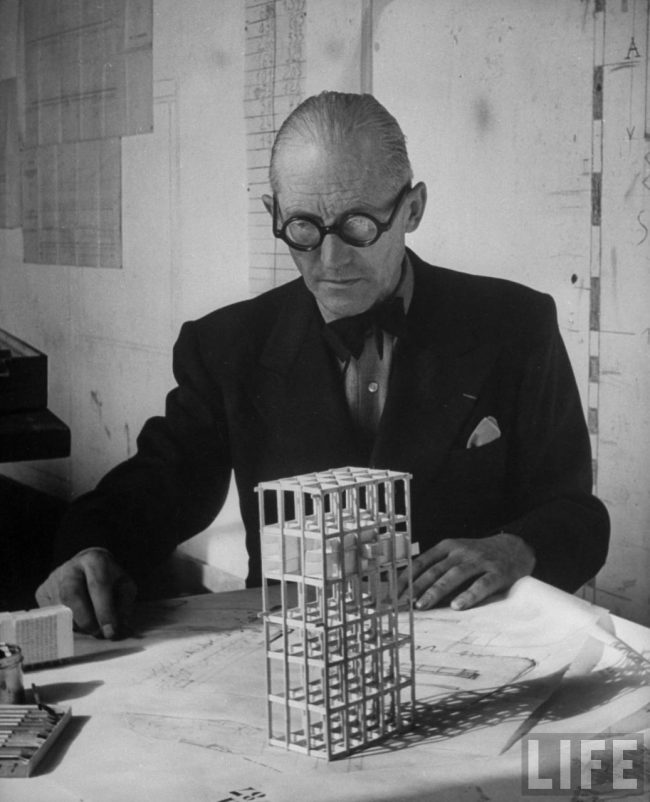

Bespectacled urban planner Le Corbusier was as bold as his buildings, considered evil by some and a genius by others. All can agree that he wasn’t short of ambition, and rightly so. He’s one of the granddaddies of modernism and responsible for bringing in brutalism.

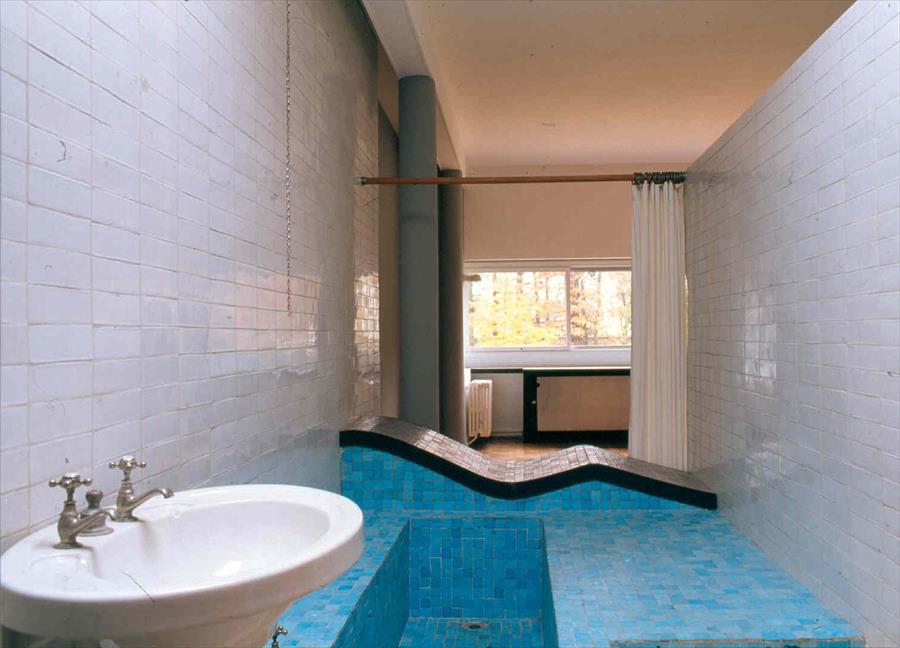

His pioneering designs centred on functionality and aesthetics while his written work acted as a manifesto for a new mode of living. Houses are more than homes, they are ‘machines for living in’. Some of his modern masterpieces are open to visitors today, such as Villa Savoye on the outskirts of Paris, and the brut-iful Unité d’Habitation in Marseille.

Le Corbusier was a forward-thinking guy, on a quest to create the ultimate utopian ‘City of Tomorrow’. He was highly critical of his field, calling architecture a profession in which ‘progress is not considered necessary, where laziness is enthroned, and in which the reference is always to yesterday’. Poised to change the game completely, in 1925 the Swiss-French architect set his sights on Paris; a dream canvas to realise his visions of a futuristic city and put them, literally, in concrete form.

First off, let’s give the man some credit for his good intentions before things get ugly. The reasoning behind his Parisian neighbourhood plan, or ‘Plan Voisin’ as it’s known, seemed pretty solid, with social reform at the heart of the blueprint. Whether it would have actually worked or ended up as a dystopian nightmare, we’ll luckily never know.

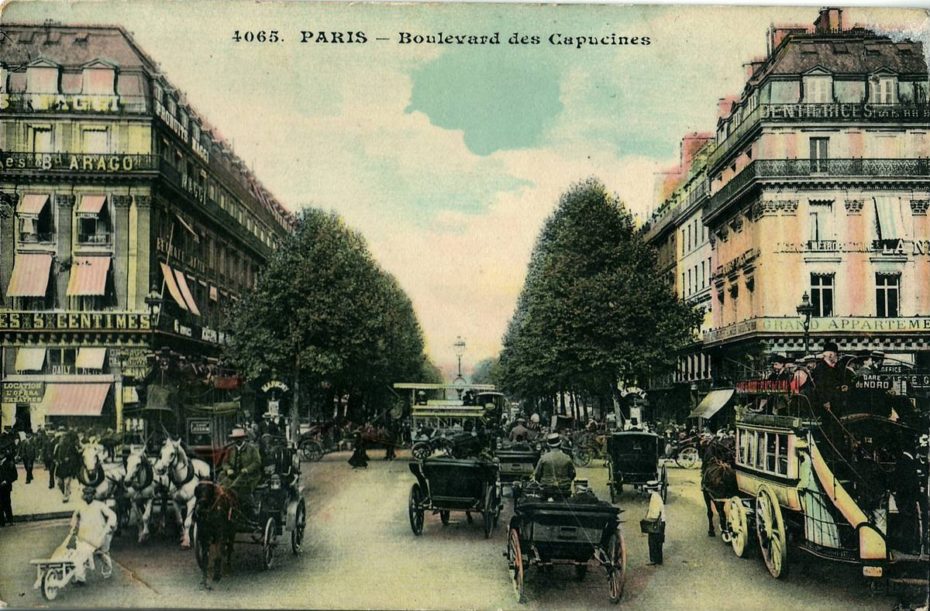

At the start of the 20th century, Paris was finally nearing the completion of Haussmann’s renovations, which included doubling the size of the city, building beautiful parks and creating a network of boulevards. In essence, putting the final touches on the picture-perfect Paris we know and love today.

Le Corbusier argued that this new urban layout exacerbated economic segregation; separating neighbourhoods with wide avenues and pushing poorer Parisians out to the disease-ridden slums.

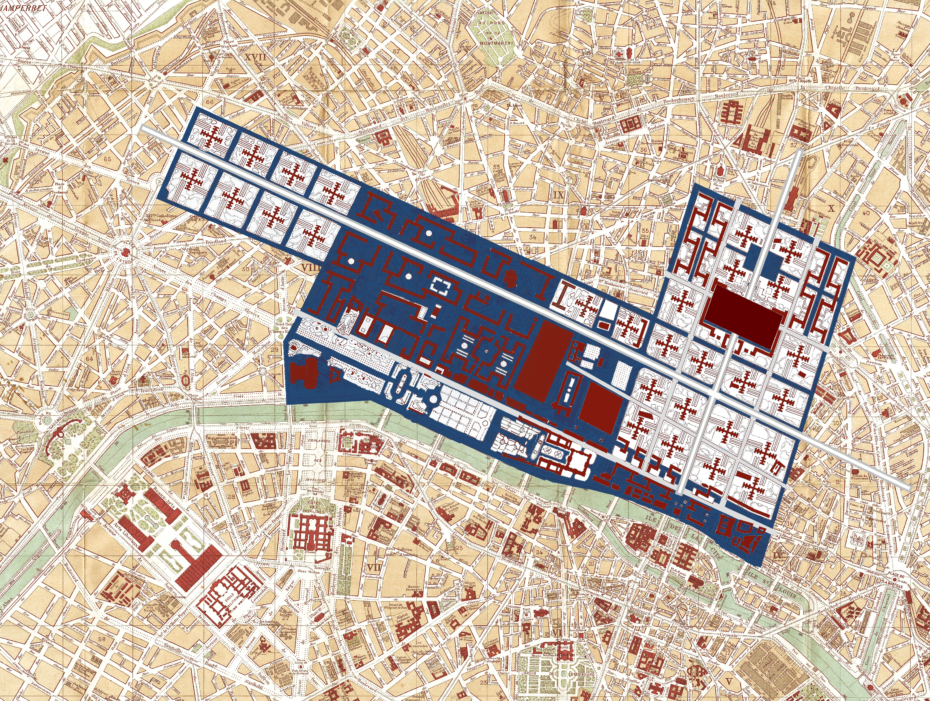

Armed with answers to the city’s urban crisis, the first step of the plan was to destroy everything in sight. The nuclear option, naturally. Paris as a whole would be transformed but it was the ancient 3rd and 4th arrondissements on the right bank that would take the biggest hit and be demolished completely. Although today the lively Marais neighbourhood is home to the city’s most interesting and inspiring architecture and culture, at the time it was characterised by sickness and squalor and deemed inhabitable. Sounds heart-breaking with hindsight, but in 1925, bulldozing this historic quarter and starting afresh did make a lot of sense to a lot of people.

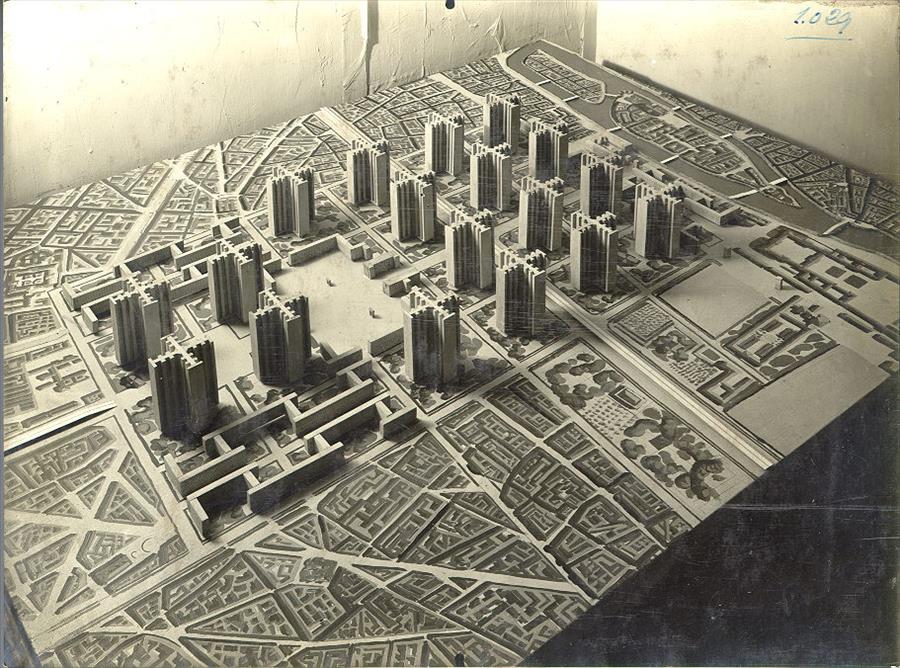

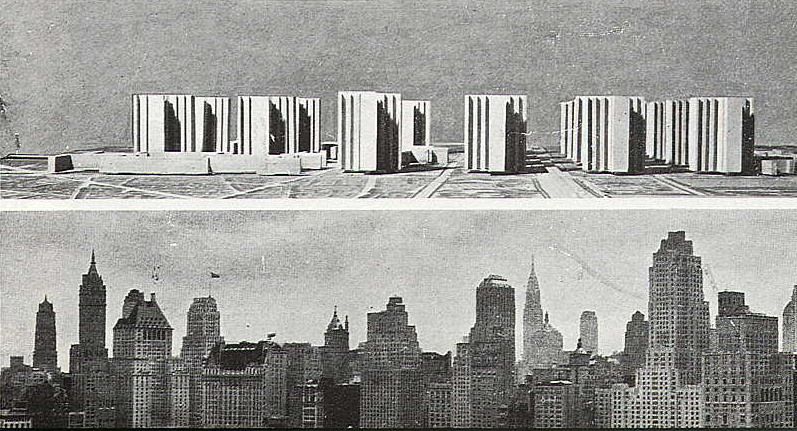

Unlike some of Le Corbusier’s iconic future projects, primary colours and stylish curved roofs were out the window. As were architectural styles that drew on tradition rather than modernity. Le Corbusier’s ‘Plan Voisin’ consisted of 18 cruciform skyscrapers in a giant rectangular grid, separated into commercial and residential zones which would be connected by highways and a transport interchange.

In between the towering monoliths you’d find vast green space and tree-lined walkways leading up to cafés, offices and shops all located at the bottom of each glass fronted block. It was a machine-like set up that could be adapted to any city. Oh, and there’s an airport plonked in the middle of it too. Sounds… charming?

Le Corbusier tried his best to romantically market his version of a fully functional urban utopia. He asked would-be displaced residents to picture the huge office blocks ‘flashing in the summer sunshine, softly gleaming under grey winter skies and magically glittering at nightfall’. Sold yet?

Can you imagine Hemingway, Fitzgerald and other bright minds of 1920s Paris flâneuring around a construction site? Or what about Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke, take-out coffee in hand, on their 50th lap of a rooftop garden while they ponder life against a backdrop of landing planes and the setting sun? Nope, me neither. ‘Emily in Paris the Eastern Bloc’ would sure be a very different TV show.

As you might have guessed, the high-rise horror of the ‘Plan Voisin’ got canned before demolition ensued. It was a close call but thankfully the proposal was rejected despite Le Corbusier’s unrelenting promotion in journals and at international expositions. The outcry from heritage lovers strengthened Paris’ preservation movement, but also helped publicise Le Corbusier’s prefab principles far and wide, planting the seed for other cities to consider his dramatic designs instead.

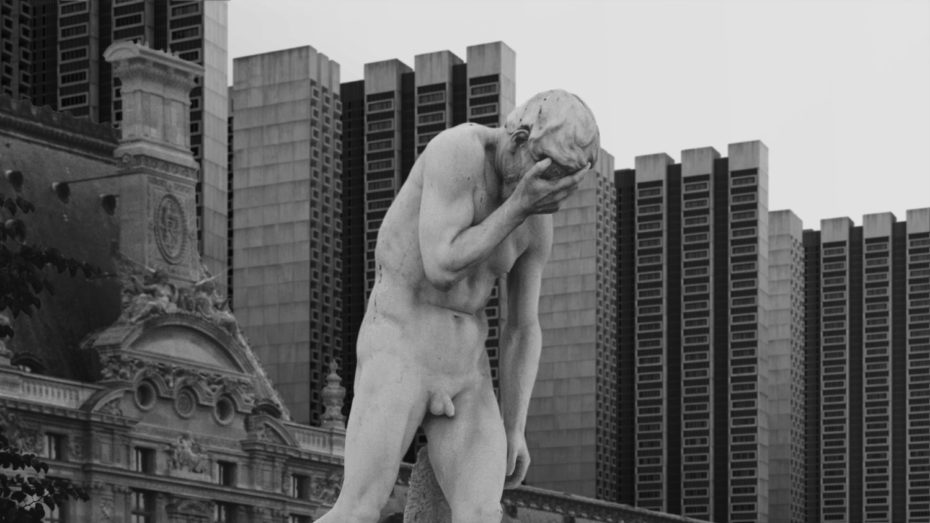

Maybe we would have grown to love, or at least get used to, Le Corbusier’s grand design if it did make it into concrete form? Haussmann was similarly a controversial figure who, in his own words, ‘ripped out the belly of old Paris’ to make way for a modern new world. He too was met with scepticism, but things seemed to have worked out for him? Today we coo over his creations that are so integral to French culture and character. His version of Paris is overwhelmingly adored and fiercely protected. For example, the guttural throwing up of the Montparnasse Tower, which sticks out like a sore thumb above the cityscape in the heart of Hemingway’s Paris, is categorically considered a grave error in urban planning and as a result a strict height limit is now enforced…

Paris’ Right Bank had a lucky escape, but alas, Le Corbusier did manage to make his modernist megaproject, albeit far away from his European roots. In the 1950s, the young republic of Chandigarh, “India’s Overlooked Concrete City of Oz” was keen for a new look as a way to draw a line under its imperial past and carve itself out as a ‘City of Tomorrow’. Finally, putty in the hands of the urban planner…

Back in Paris, the story doesn’t end after the failed ‘Plan Voisin’. Although Le Corbusier’s lofty visions of monolithic living were deemed totalitarian by some and politely a little farfetched by others, today his radical ideas are now the norm in many metropolises. Just look at the sky-high vertical villages of New York, Tokyo and London.

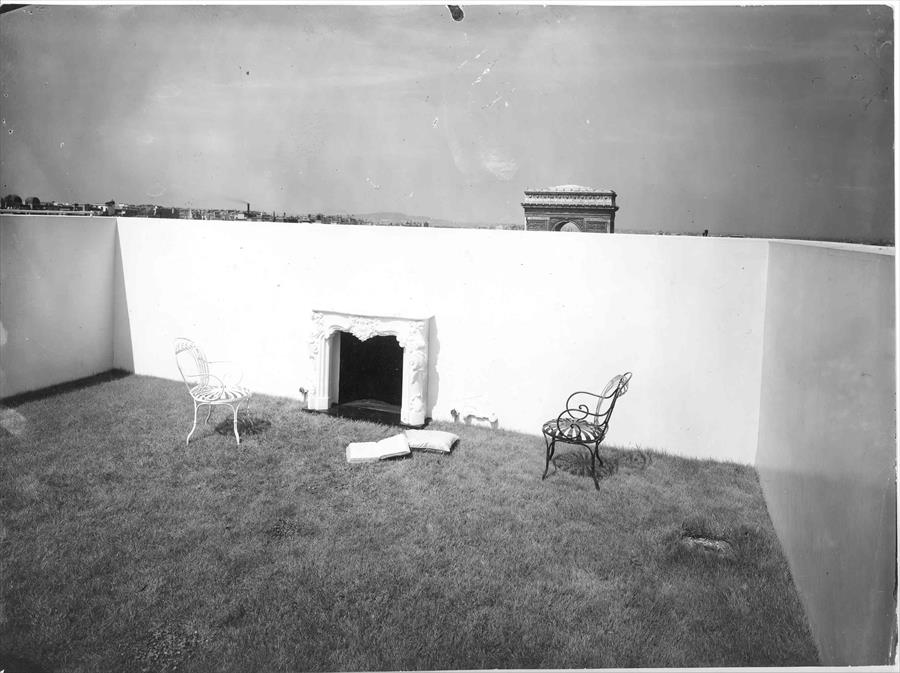

Even in perfectly preserved Paris, his influence looms heavy over the city like a dark shadow. Peer in a straight line from the Arc de Triomphe, you’ll see the imposing island of La Défense in the distance. This cluster of corporate skyscrapers was modelled directly on ‘Plan Voisin’ and serves as an ominous reminder of what could have been for the whole city. Sneaking within the city limits, a mini materialisation can be found on the left bank in the form of the 22-story high Bibliothèque François-Mitterrand.

Preserving Paris as the City of Light rather than the City of Height is a constant battle. Project ‘Plan Voisin’ was over before it began but ghosts of modernist futures haunt the historic metropolis. Nostalgia lovers know the urban fabric is a tapestry too precious to tear up and start again. The streets are grand and gorgeous but also higgledy-piggledy in parts, messy chic, if you like! In the face of cities racing onwards and upwards to reach tomorrow first, à la The Beatles, I believe in Yesterday.