In 1918 a group of American men and women from the American Red Cross wound up in Siberia where they encountered 782 Russian summer campers and their teachers. The schoolchildren were from Saint Petersburg, and had been away at summer camp when a violent war broke out. They fled the fighting by heading east to Siberia, further from home. Over the next two years, the team of Red Cross men and women traveled with these 782 children across the globe with the help of Japan, Great Britain, France, Panama, the United States, Finland, and Russia, all working together to see the children finally return home. As talk of a new war between Russia and the West looms, perhaps it’s stories like this one that need retelling…

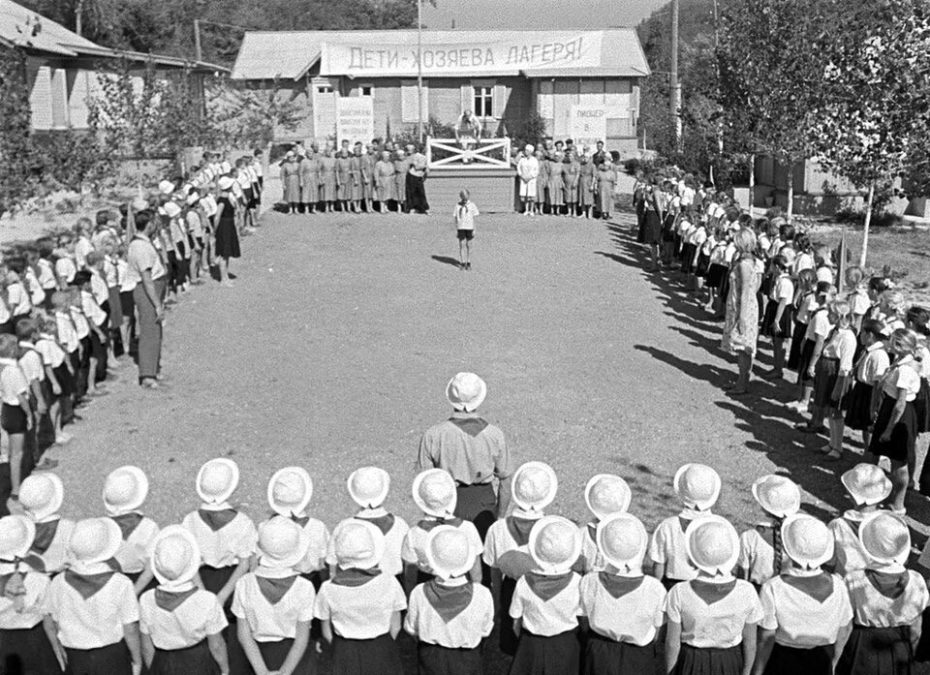

In May 1918, a group of nearly 800 boys and girls, aged between 3 and 17, left Petrograd, Russia (now St. Petersburg) for the Ural Mountains, two thousand miles south east. The Union of Cities, a charity organization, offered their “summer nutrition camps” as a way for Russia’s youth to eat well and be safe from ongoing fighting in the wake of the Great War and the October Revolution that brought the Communists to power. Food that had come from southern Russia was not getting to the cities and parents were watching their children starve. The Urals however, offered an escape. The region was now home to many deserted lakeside summer houses and resorts where the kids could set up camp (the owners had fled when the Communists took power). There, the children took lessons in reading and writing in the morning, then hiked, swam and picnicked in the afternoons. They formed theatre clubs and choral groups, put on evening concerts and even created their own newspaper and makeshift natural history museum.

But peace in paradise did not last. War came to the area in late July as Czech soldiers found themselves trapped in Russia on their journey home from the battlefields of World War I. The new Communist government demanded they surrender their weapons, but the Czech soldiers refused, fearing they would be forced into labor camps. So they decided to hold their position in the Urals and fight it out. Caught in the crossfires at the epicentre of the frontline, the summer camp suddenly went from vacation mode to survival mode. Younger students formed groups under teachers for protection while older children tried to fend for themselves, sheltering in feral conditions amidst the fallout of a civil war. The Siberian winter was coming. They had no winter clothes and money and food supplies were rapidly running out.

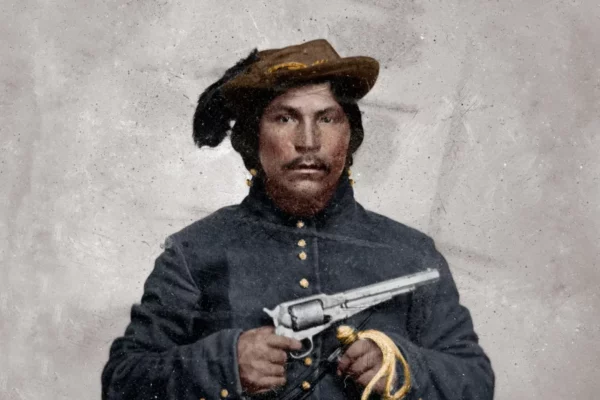

American National Red Cross photograph collection (Library of Congress)

Meanwhile back in Petrograd, parents grew alarmed. Letters from the children and their teachers had stopped. News eventually filtered back that war had broken out in the Ural Mountains and that the rail lines between them and their children were severed. As winter approached, the parents met and drew up a plan of action. One father, a cello player, Valery Lvovich Albrecht, agreed to go on a dangerous mission to locate his two daughters and the rest of the Petrograd children. He brought with him another father and a Swedish pastor of the Red Cross. Valery and these two fellow rescuers walked east along the train tracks, carrying the printed names of every last missing child. Each parent had signed their names next to their child’s name as reassurance that they were alive and desperate to know what had become of their children. Amazingly the fathers and the pastor made it to the children by foot. The campers were trapped but somehow surviving the winter. The visiting party from Petrograd offered hope, but could not offer a way home. Too many miles of broken track and battle lines blocked their return to Petrograd. The men returned home alone, carrying with them only letters from the children and bittersweet news for the parents.

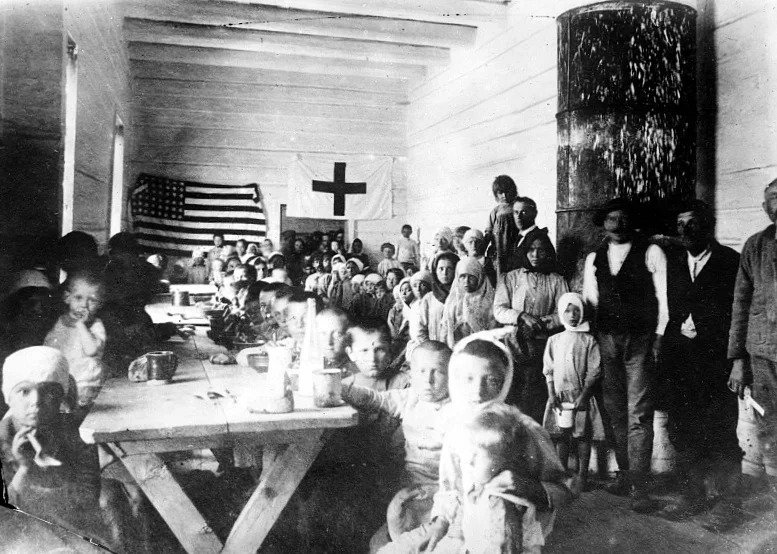

Meanwhile in Moscow, the new Communist government expelled aid workers from organisations that had been welcomed by the old Czarist government. Two aid workers from the Young Men’s Christian Association, Alfred and Katia Swan, fled eastward to the Czech-controlled areas. It was there that they heard about the lost Petrograd children and decided to travel to one of the tiny Siberian towns where they were last spotted. They found them, still wearing summer clothes and worn out shoes, hiding out in crumbling buildings. Alfred got to work getting the word out about the helpless refugees, sending out telegraphs to any organisation in Russia that might be able to help. Some of these messages reached the port of Vladivostok in eastern Russia, near Japan where an American Red Cross effort was helping Czech refugees escape.

Riley Allen was head of this Red Cross relief effort and responded to the Swans’ telegram: “All children will be taken care of by American Red Cross. Take charge of work. Meet first representatives at Omsk and get money and clothing for the children!” The Swans received permission from a Czech military commander to head east with financial aid for the children. Students received warm clothing and started to return to their studies amidst the rubble. Native Hawaiians sewed winter clothing and knit sweaters with tags that read “Aloha Nui Loa,” (very much love). Many of Allen’s staff of Red Cross doctors, nurses, and aid workers were native Hawaiians who volunteered to travel to Siberia.

Just as the students were beginning to find a routine again thanks to the help of relief workers, the summer of 1919 saw more violent fighting erupt in the area. The decision was made to evacuate the children deeper into Siberia to the Red Cross barracks in Vladivostok. Children crammed onto barges, standing shoulder to shoulder without a break for two and a half days. One student, Jonah Gurshman wrote in his recollections, “Many, especially children, as soon as they descended the gangway, fell to the ground and immediately fell asleep, they had to be woken up to eat… the memories are hard…”

Vladivostok served as a temporary home to the students, but their journey was far from over. When the Japanese Army invaded Vladivostok, forcing the American troops to vacate the port, the Red Cross had no choice but to leave the children behind. Riley Allen then pleaded with the Japanese for help and managed to find a Japanese freighter, the Yomei Maru, to evacuate the children. The ship’s owner took pity on the Petrograd children and equipped the steamship with beds and an infirmary to sail them home safely at his own expense. Little did they know, the ship would be setting sail for a round-the-world journey. Initially bound for France, the shorter route across the Indian Ocean would have been too dangerous in the sweltering heat of summer, so the vessel set course across the Pacific Ocean with stops in Japan, California, before passing through the Panama Canal and stopping in New York City. When students arrived on Staten Island, they were encouraged to find new homes with foster families, relatives in the US or settle for a refugee camp in France where they might eventually be reunited with their parents. Three students accepted to stay in America, but the rest preferred to continue their journey.

Desperate to return home, the schoolchildren made public speeches to several hundred people at Madison Square Gardens, wrote petition letters to the Red Cross and told their story to the press. News of their plight even reached President Woodrow Wilson and his wife. The students were grateful to the Red Cross for all they had done, but they demanded to be returned to Petrograd, Russia. Behind the scenes, Allen kept pressure on the Red Cross and finally, the students were allowed to return home. As they sailed toward Russia via Finland, Allen finally was able to work with the Communist government in Petrograd. He located each set of parents to inform them that their children were alive and well. By January 1921, two and a half years after they had left for camp, the Petrograd students were returned to their parents at the very same train station where they’d first said their goodbyes for the summer. They had literally circled the globe to get back home.