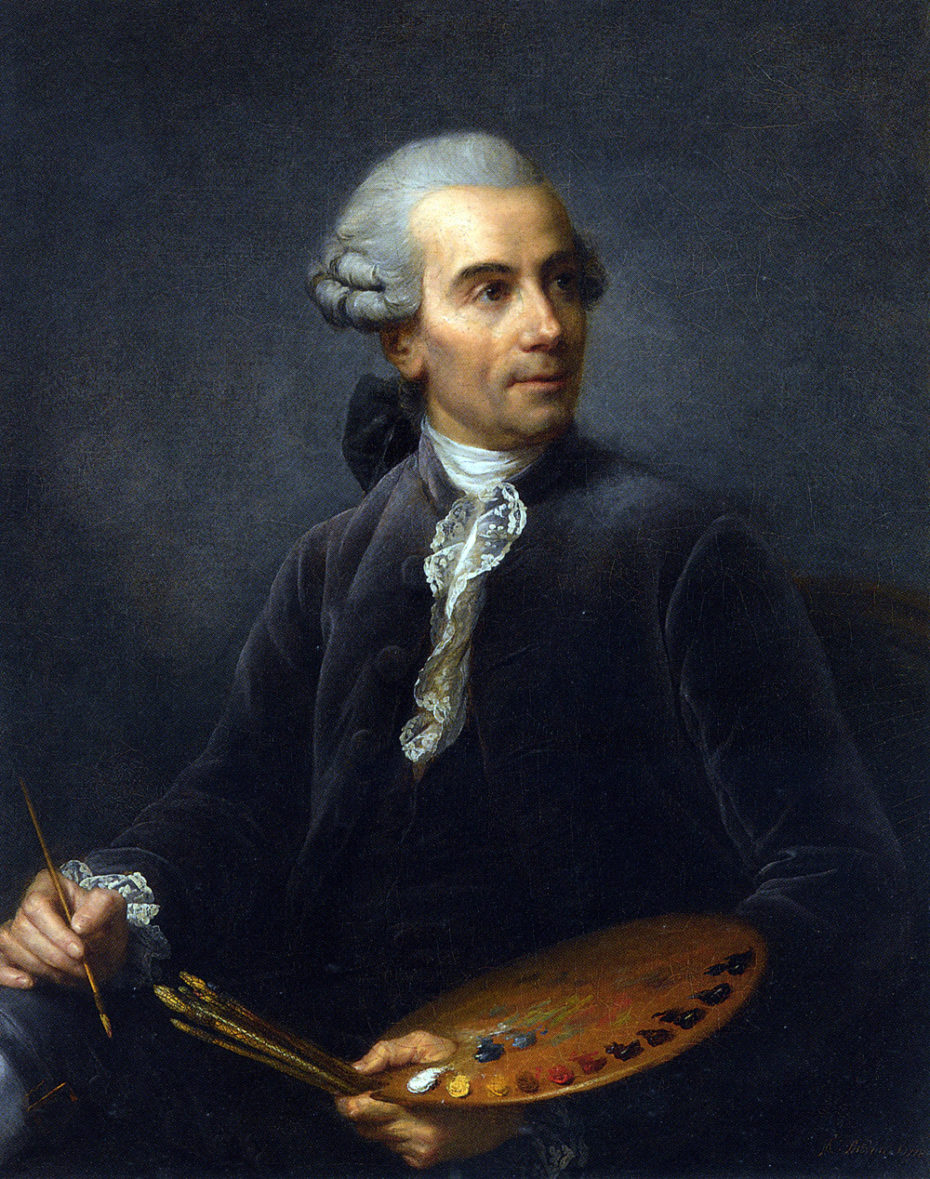

What if we told you that just about every painting you’ve seen of Marie-Antoinette was created by a woman? Overlooked for two hundred years, Élisabeth-Louise Vigée-Le Brun was one of the most celebrated portraitists of the late 1700s. She painted all of the most glamorous women of the Versailles court and some of the most powerful men in Europe. As the queen’s favourite painter, Vigée-Le Brun painted thirty portraits of Marie Antoinette, including her most scandalous portrayal in a simple white muslin dress, deemed too revealing and inappropriately pastoral for the monarch. In 1789, when the Revolution broke out, Vigée-Le Brun escaped Paris with her daughter and painted her way through the royal courts of Europe.

Vigée-Le Brun was born in 1755, the same year as Marie-Antoinette. The daughter of Louis Vigée, a pastel portraitist, she grew up among artists with a witty father who gave her drawing lessons and encouraged her talent. He died when she was twelve, leaving her devastated and the family penniless. Her mother, Jeanne (née Maissin), soon married a goldsmith whom Vigée detested.

As a woman, Vigée was denied the usual apprenticeship system of the Académie Royale. She did receive some instruction from friends of her father, but her art education was largely thanks to her mother, who chaperoned her to the galleries of the Luxembourg Palace, where she copied Old Master paintings. By the time she was 17, she was making a living as a portraitist. She was prolific enough that she attracted the attention of the authorities and in 1774, her studio was padlocked and the contents seized because she was working professionally without being affiliated to a guild. Barred from the Académie Royale, she joined her father’s guild, the second-tier Académie de Saint-Luc.

Vigée and her family moved into an apartment at the Hôtel de Lubert, where renowned art dealer Jean-Baptiste Pierre Le Brun was also living. After six months of admiring Le Brun’s incredible art collection, Vigée married him in 1776. Le Brun championed her work and introduced her a wide circle of leading painters of the time, but unfortunately, he also pocketed most of his wife’s income to fund his gambling addiction and satisfy an insatiable desire for paintings and objets d’art. Nevertheless, with so many portrait commissions coming in, the Vigée-Le Bruns were soon able to buy their house. Between the two of them, the Hôtel de Lubert became one of the most fashionable artistic salons in Paris. Most of the 17th century mansion located at 19 rue de Cléry has lost its original character, but the doorway and garden-facing facade are still intact.

In 1778, Vigée was summoned to Versailles to paint Marie-Antoinette for the first time. The painting was to be a gift for Marie-Antoinette’s mother, Empress Maria Theresa. Consequently, it’s a very regal and formal portrait. Marie-Antoinette is in full court dress, wearing a corset (which she hated) and a white satin robe de cour, floofed out with enormous side hoops. In case all the ribbons, lace, feathers, and gold tassels aren’t enough to telegraph her elevated station, she is surrounded by symbols of her royalty. Carrying the pink rose of the Hapsburgs, she stands next to a table bearing the French crown. A huge marble bust of her husband on a gold pedestal looms above her. Empress Maria Theresa loved it and Marie-Antoinette was relieved that her demanding mother was pleased.

As she became known as Marie-Antoinette’s favourite painter, Vigée-Le Brun was determined to be admitted into the Académie Royale. What’s more, she wanted to be accepted for the most prestigious genre; historical painting. Accordingly, for her morceau de réception (reception piece), she applied with Peace Bringing Back Abundance, a historical allegory depicting Peace draped in a dramatic green cape and bare-breasted Abundance with a basket of fruit. The painting is fascinating for the lighthearted Rococo style of the Abundance figure meeting with the dramatic new Neoclassical style of Peace. Her application was rejected – not only was she a woman, but she was also married to an art dealer, violating their bylaws forbidding artists from mixing in commerce.

It took a royal decree from the King, presumably with a little persuasion from Marie-Antoinette, for Vigée-le Brun to be accepted into the Académie Royale in 1783, along with three other women. Her public debut at the Académie Royale that summer caused an uproar.

Besides Peace Bringing Back Abundance, Vigée-Le Brun’s exhibit consisted of a self-portrait in a jaunty straw hat and a stunning portrait of the notorious courtesan Madame Grand.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Edward S. Harkness, 1940.

Visitors to the salon, however, were shocked to see her portraits of the Comtesse de Provence (Marie-Antoinette’s sister-in-law) and Marie-Antoinette. “The two princes are ‘en chemise’,” reported the gossip sheet Memoires Secrets, “Many people have found it inappropriate to portray these august personages in public in a garment reserved for the interior of their palace.”

At the time, a chemise was worn under a dress. The Memoires Secrets was saying that Marie-Antoinette and the Comtesse de Provence looked like they were in their underwear. Moreover, cotton came from the British colony of India. As an Austrian princess, Marie-Antoinette was already under scrutiny for her allegiances. Wearing a cotton gown was seen as incredibly unpatriotic and confirmed public opinion that she didn’t have the interests of France at heart. There was a huge backlash and the painting was removed in less than a week.

Vigée-Le Brun responded by quickly painting another portrait of Marie-Antoinette. Her face and hands are in the same position, but this time, she is attired in a robe à la polonaise made of grey silk trimmed with delicate lace. She is simple but opulent, with a gown that proclaims her support for Lyon silk and Chantilly lace.

Like her queen, however, Vigée-Le Brun continued to rebel against the stiff formality of the French court. She painted Marie-Antoinette’s fashionable friends in simple muslin frocks, helping to establish this budding new fashion.

She encouraged the Duchesse de Caderousse to leave her hair unpowdered and loose, setting the trend when she went straight to the opera afterwards. Her subjects lean on their elbows, lips slightly parted as if in the middle of a conversation, which they probably were. She painted Charles-Alexandre de Calonne, the powerful Controller General of Finance, with wig powder dusting his shoulders.

Vigée-Le Brun caused another outrage at the 1787 Académie Royale salon with her latest self-portrait. Clad in a muslin dress with a ribbon adorning her unpowdered hair, she cradles her daughter Julie with a tender smile, showing a small hint of teeth. The Académie was appalled. An ambiguous smile was one thing, but a smile with teeth was “an affectation which artists, art-lovers and persons of taste have been united in condemning,” bristled Memoires Secrets, adding, “This affectation is particularly out of place in a mother.”

Vigée-Le Brun’s last portrait of Marie-Antoinette was commissioned in 1788 as a piece of propaganda to restore the queen’s public image. A massive state portrait, standing nine feet tall, Marie-Antoinette is depicted in a red velvet gown surrounded by her children, evoking Madonna paintings of the great Renaissance painter Raphael. She holds her younger son in her lap, while her daughter leans against her and looks up at her adoringly. The Dauphin stands next to her, pointing to an empty bassinet, where baby Sophie would’ve been painted if she hadn’t died before the completion of the painting.

By then, the situation in Paris had gotten ugly. A mob surrounded Vigée-Le Brun’s carriage one night and a man climbed up the carriage steps shouting, “Next year you will be behind your carriages and we shall be inside!” Vandals routinely attacked her studio. Depressed and terrified, Vigée-Le Brun realized that she was in danger and needed to leave. In 1789, on the night that a mob descended on Versailles and arrested the royal family, she grabbed her nine-year-old daughter and they stole out of France.

Making the best of the situation, Vigée-Le Brun decided to go to Rome, where she could continue to study the Old Masters. In six months, she thought, it would be safe to return home. Little did she know that it would be twelve years before she saw Paris again.

In Rome, she painted a self-portrait for the Florence Gallery, depicting herself sketching a figure that looks a lot like Marie-Antoinette. She also created a Neoclassical painting of Miss Pitt as Hebe, the Roman goddess of cups, along with a terrifyingly enormous eagle kept on a leash, which continually tried to attack her.

From Rome, she went to Naples, where she stayed with Marie-Antoinette’s sister, the Queen of Naples. She visited the British Ambassador, Sir William Hamilton, who requested that her first portrait be of his ravishing mistress, the scandalous Emma Hart. Considered by many historians as the world’s first supermodel, she was soon to be Lady Hamilton before starting a hot-and-heavy affair with a British Navy hero. Vigée-Le Brun painted several mythological portraits of Lady Hamilton in a mix of lyrical Rococo style and Neoclassical history painting.

As Ariadne, Lady Hamilton reclines on a leopard skin in a seaside grotto fondling one of Lord Hamilton’s ancient Greek vases. As a hedonistic worshiper of Bacchus, she dances with a tambourine in front of a smoking Vesuvius, which could be seen from Lord Hamilton’s property. In Vigée-Le Brun’s favorite painting, she is the Cumaean Sibyl, pausing to receive inspiration as she writes. Vigée-Le Brun took this last painting with her as a sort of calling card, “My Sibyl, which people came in their droves to admire, played no small part in convincing people to ask me to paint them.”

Meanwhile in Paris, Vigée-Le Brun’s name was added to a list of émigrés who had escaped “revolutionary justice” and she lost her citizenship. Her husband, who had remained in Paris, appealed to the Legislature to no avail. He then conscripted her brother, who had made his name as a writer, to pen a lengthy defence. They were both briefly arrested for their efforts. At the height of France’s post-revolutionary Reign of Terror in 1794, with no other recourse, Le Brun filed for a divorce on grounds of desertion in order to safeguard his life and his property.

Vigée-Le Brun continued to hopscotch through Europe. In 1795, after a grueling three month trip, she and her daughter arrived in St. Petersberg. She spent the next six years painting Russian nobility at the court of Catherine the Great, who was gracious, but not entirely pleased with Vigée-Le Brun’s work. She detested Vigée-Le Brun’s portrait of her granddaughters and never sat for a painting. Vigée-Le Brun did create one of her masterpieces while in Russia, a glowing portrait of her friend, Countess Golovine, her hair loosely bound with a mustard-coloured scarf, gazing at the viewer with warmth and candour.

In 1800, Vigée-Le Brun’s name was finally struck from the list of émigrés and she was allowed to return to Paris. Her daughter Julie, however, had fallen in love with Gaetan Bernard Nigris, secretary to the Director of the Imperial Theatres of Saint Petersburg. Against her mother’s wishes, Julie married Nigris. Heartbroken, Vigée-Le Brun set off alone on the long road back home. She only reunited with her daughter a few years before Julie died of syphilis in 1819.

Vigée-Le Brun returned to Paris in 1802, only to discover that she was more in demand outside of France. Her only Imperial commission was a full-length portrait of Napoleon’s sister, Caroline Murat, in 1807. For the next several years, she continued to travel, spending many months in Switzerland and three years in London where she painted a teenage Lord Byron. In 1809, she settled once again in Paris and started receiving people in a salon that became a meeting place for the Romantic school.

Vigée-Le Brun lived until 1842, seeing the end of the Napoleonic era and the restoration of the monarchy. Despised as a royalist during the Revolution and forgotten after the advent of Romanticism, she faded into obscurity despite an impressive body of over 600 portraits that documented some the most important people of her era. An important painter who lived a remarkable life, she deserves to be better known.

About the Contributor