In an age where we almost entirely rely on our smartphones and satellites orbiting Earth to tell us what direction to go in, imagine traversing thousands of miles of open ocean using only your senses. This is how the first people who populated the islands of the Pacific Ocean traveled, and some still do, relying on generations of knowledge passed down from masters to apprentices. There’s much that can be learned from orienting oneself using clues from the natural world around us, so take a moment to step out of the GPS bubble and lose yourself in the ancient, endangered art of wayfinding…

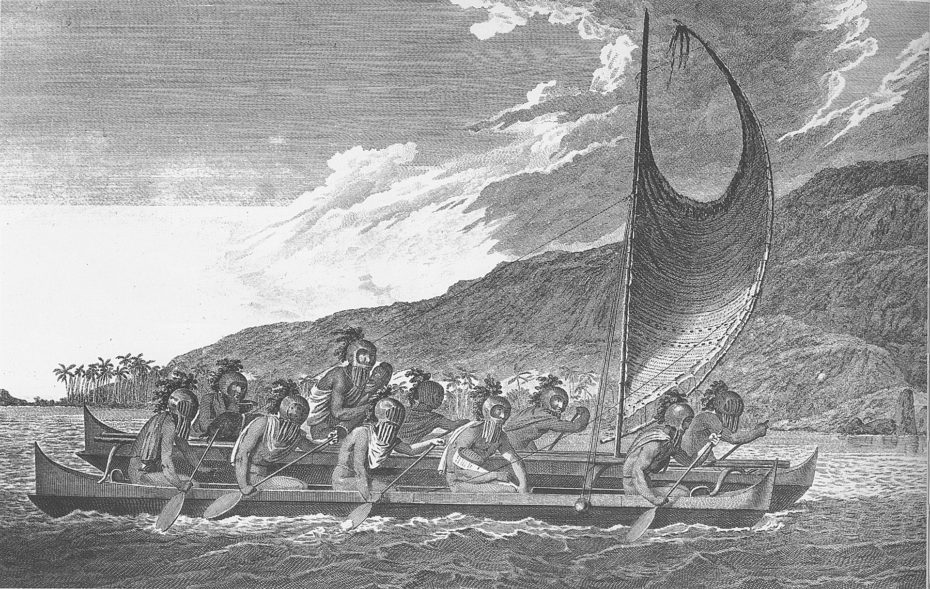

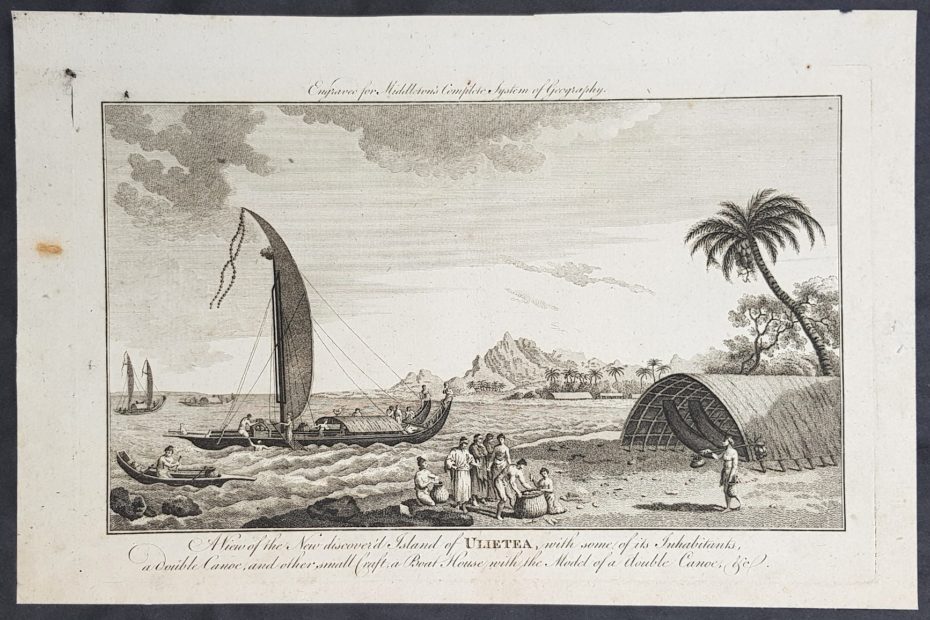

Traveling by canoes, Polynesians made contact with almost every island (there are over a thousand of them) in the expansive Polynesian Triangle, whose corners are made up of the islands of Hawaii, Easter Island and New Zealand. The Pacific Ocean itself is larger than all the continents combined. The geography of Polynesian navigation pathways resembles an octopus. The head is located on Raiatea (in modern-day French Polynesia) and the tentacles extend through the Pacific Ocean. Archeologists generally agree that initial settlement of the Cook Islands began before 1,000 AD and exploration expanded from there. Polynesians relied on oral traditions, largely songs, to find their way, as well as wayfinding techniques including monitoring stars, birds, ocean swells and wind patterns. While these navigation strategies, as well as the construction of outrigger canoes that could hold materials for long trips, were almost lost, they are now being recorded in an era of renewed interest in their history. Current-day navigator and Hawaiian son Nainoa Thompson told Maui Magazine that these ocean voyagers were “the astronauts of our ancestors, the greatest explorers on the face of the earth.”

Historically, guilds of navigators held privileged positions on islands; during periods of famine or other threats to their existence, Polynesians relied on these guides to find new islands to inhabit. Part of the traditional coming of age for a man was to be stranded well over the horizon from any islands and for the young man to then navigate back on his own. Explorers like Captain James Cook took Polynesian navigators on their voyages to help catalogue the region, although their knowledge was often wrongfully disregarded.

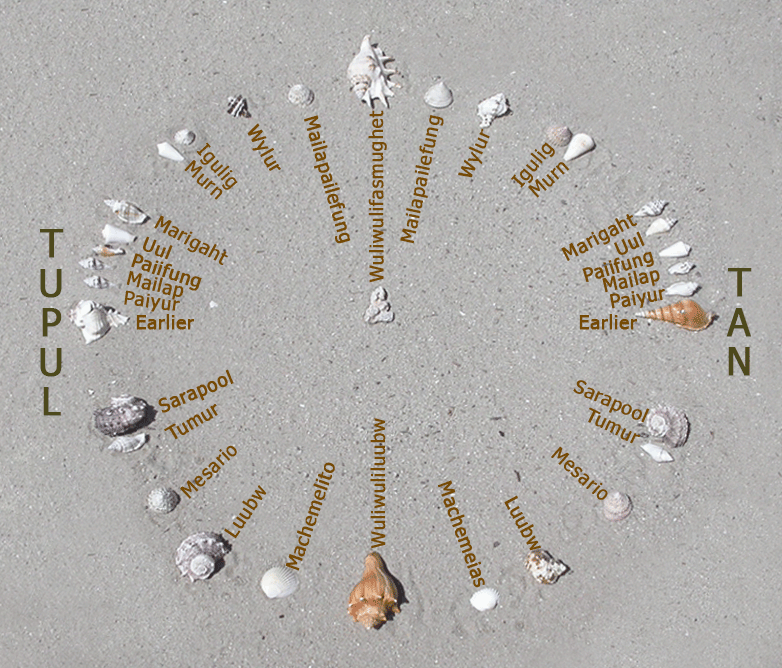

Much of Polynesian navigation is a combination of memorisation and constant observation, with the location of the sun throughout the day providing the most reliable locator and stars taking its place after sunset. Navigators would use a star compass, drawn in the sand with shells to represent the constellations, and memorise a specific star sequence for each route. This compass showed a 360-degree horizon aligned with cardinal directions and the canoe is centred in the middle, with stars moving through different points during the night.

The local environment was also a crucial navigational tool. Birds like the White Tern left their homes to go hunting for fish in the mornings, so navigators went in their direction to reach land. Some took so-called shore-sighting birds on board with them, such as the frigatebird. They released the bird when they felt they were nearing an island and followed it to shore. Clouds too were a reliable tool, given the specific shapes that form from the reflection of coral atolls’ white sand or how lagoons can give clouds a green tint.

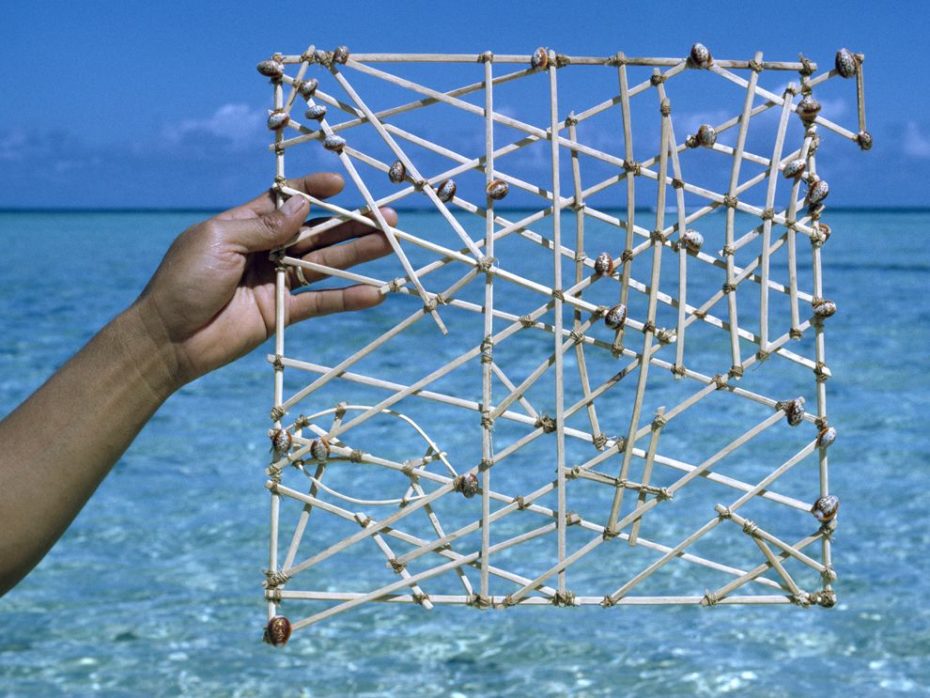

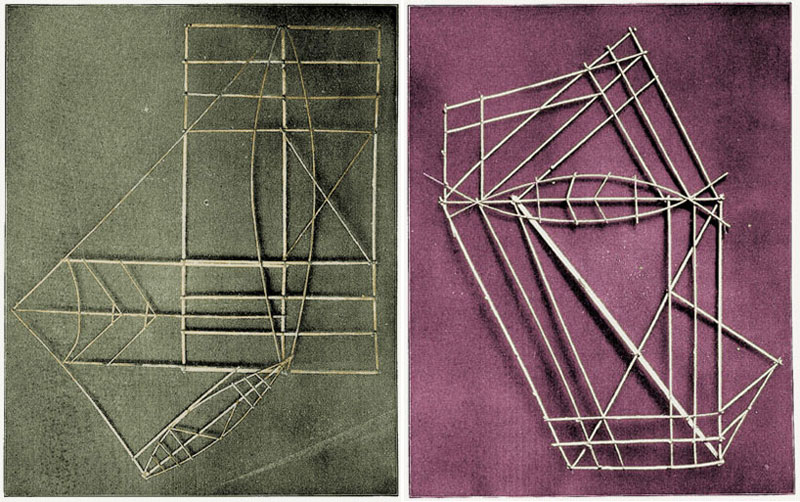

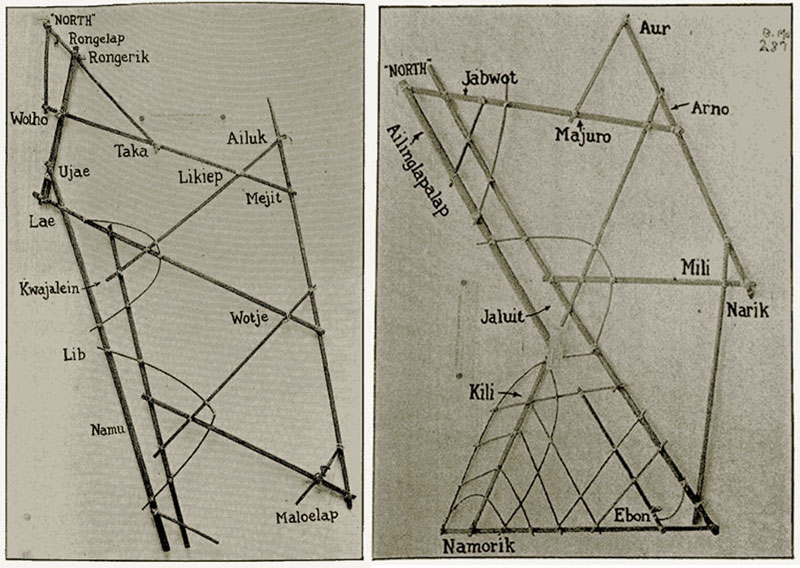

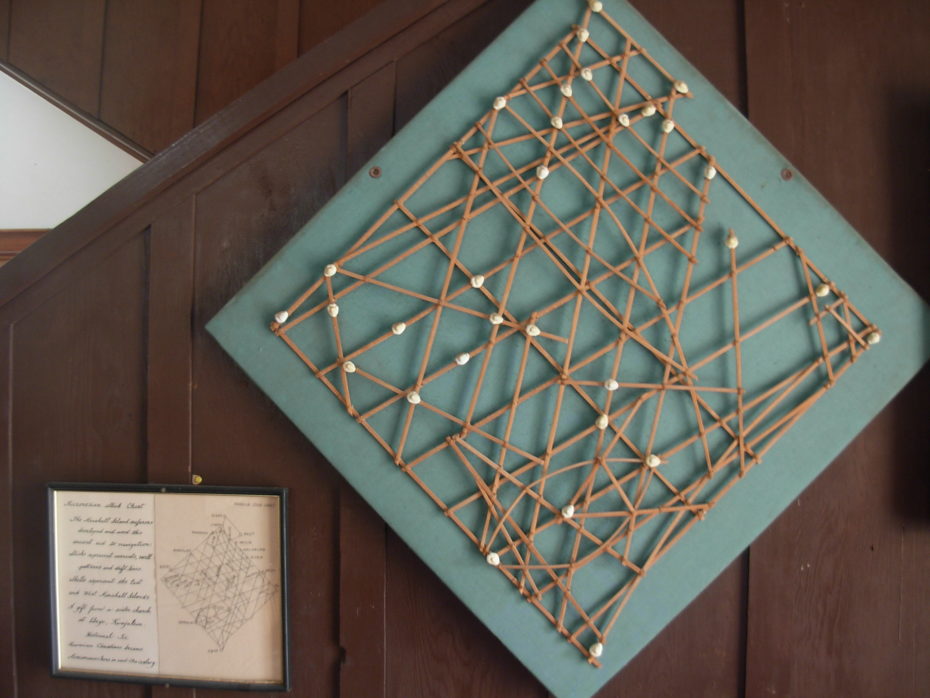

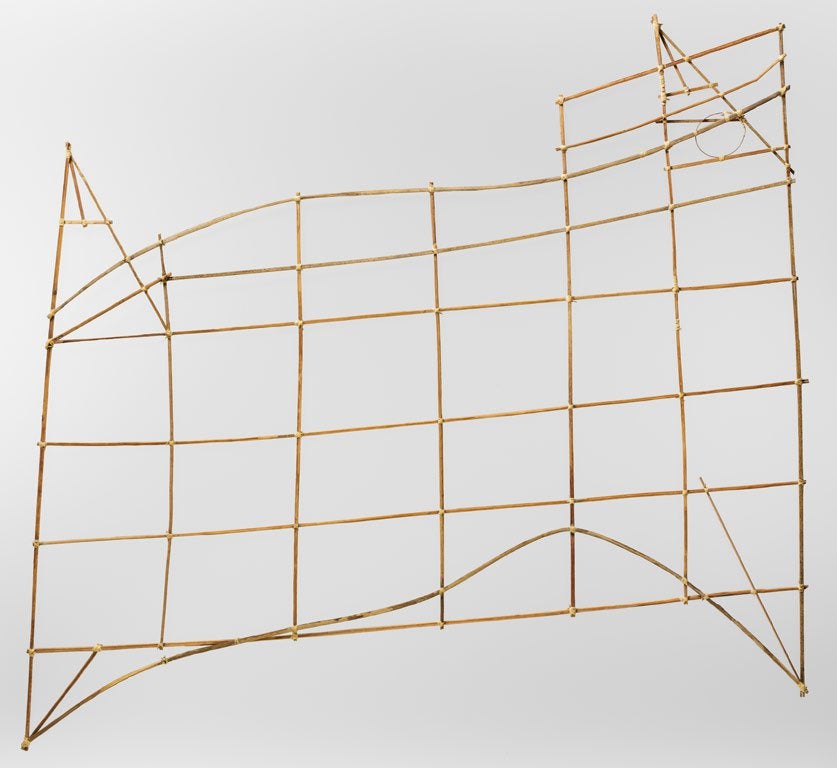

Polynesians did also rely on a form of a physical map called a stick chart, illustrating the specific wave and swell patterns surrounding different island chains. These were particularly helpful during cloudy conditions when the sun and stars were less useful. To navigate the Marshall Islands, the Marshallese represented ocean swell patterns using parts of coconut fronds and shells as islands. Like a subway map, they don’t so much represent distances as they do relationships. The complex and decorative stick charts were often only understood by the person who made them. They were memorised before a voyage by the pilot who would lie on the floor of a canoe to get a sense of swell movement and often lead a squadron of 15 or more boats.

Sadly, European colonisation of the Pacific would obliterate generations of knowledge. Some historians even argued that Polynesian exploration was largely a myth and that they had just stumbled upon the islands. So in 1970, the Polynesian Voyaging Society of Hawai‘i built Hōkūle‘a, a 60-foot voyaging canoe, to prove their wayfinding abilities.

With the help of Mau Piailug, one of the last traditional navigators, they successfully traveled to Tahiti — some 3,862 kilometers. A crowd of more than half of Tahiti’s population greeted the crew when they arrived. And they made the journey again in 1980. A documentary, “The Navigators: Pathfinders of the Pacific” traces how Piailug learned wayfinding from his father and grandfather and then passed down his heritage.

Chad Kalepa Baybayan, who passed away last year after dedicating his life to preserving the art of wayfinding, told Maui Magazine that “When I sailed in 1980 it was like stepping back in a time machine. The black silhouette of a crab-claw sail against the starry backdrop . . . at that moment you are as close to your ancestors as possible.”

Since then, new generations of Polynesians have mastered the traditional wayfinding skills, but combine them with some modern scientific tools. One shift has been allowing women to take part in the sacred Pwo ceremony in which navigation students are initiated into their craft’s secrets. Between 2013 and 2017, Hōkūle‘a made an inaugural voyage around the world, a feat that involved over 200 crew members. The next trip will begin in spring of this year, with the goal of highlighting underrepresented Pacific voices and also how many of these island nations are particularly susceptible to the impacts of climate change. Matahi Tutavae is a Tahitian voyager who trained and sailed with the Hōkūle‘a and also launched the Tahiti Voyaging Society. Tutavae told the BBC that “It only takes one canoe visiting your island for that ancient memory to come back. When [Tahitians] talk about themselves now, they’re referring to their heritage and voyaging history.”