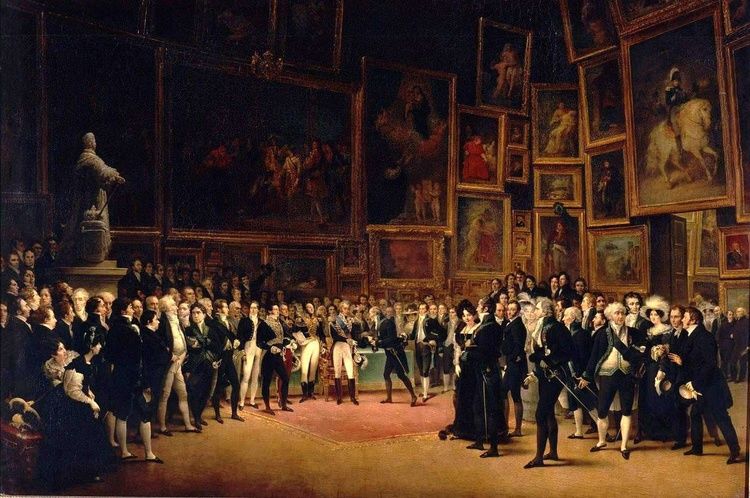

Even some of the greatest names in art history- Paul Cézanne, Édouard Manet, Camille Pissarro and James Whistler- were once rejected by the art world. In 1863, the “Salon of Painting and Sculpture” had been going for almost two centuries. Held annually at the Louvre, the show presented the work of promising young graduates from the Academy of Fine Arts and had the power to make or break careers. The royally sanctioned Salon defined the French aesthetic and even brought about the genre of art criticism. Yet it was constrained by bureaucracy and the traditional tastes of its jurors, ultimately failing to embrace avant-garde painting and recognise the emergence of a little movement called Impressionism. (Just a minor oversight). They refused Édouard Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe, today a famous and studied painting. The rejects of the Paris Salon, however, would have the last laugh. So let’s take a wander through the exhibition of rejects, or the Salon des Refusés, a groundbreaking art show that laid the foundation for modern art.

Originally, the official Paris Salon only considered works by students of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, but after the French Revolution, submissions were opened up to all artists (even foreigners). The hierarchy of genres was rigidly applied, organizing paintings in terms of subject matter, with historical paintings ranked as the most important, followed by portraits, then landscapes, then still life.

Winning a prize at the Salon was a sure harbinger of a successful artistic career as they typically led to official and private commissions. The jury, which consisted of artists and officials, tended to lean conservative. In the eighteenth and nineteen centuries, for example, they awarded prizes to neoclassical, moralising allegories like Jacques-Louis David’s The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons or patriotic history paintings like Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People In short, the Salon was a means of maintaining control over artists rather than encouraging aesthetic experimentation. But the death-grip the academy held over the French art world was about to be loosened.

As early as the the 1830s, artists who were rejected by the salon chose to band together and show their refused work at a gallery. This made few waves, however, as they were not well-known. The Salon’s control was properly challenged for the first time in 1855.

The realist painter Gustave Courbet had previously shown works in the salon, including A Burial at Ornans and The Bathers. The works caused a scandal for their questioning of the hierarchy of genres (like painting a nude outside of a classical setting). In 1855, not a single one of Courbet’s entries were accepted. Never one to miss out on a publicity stunt, the artist put up his own exhibition: “The Pavilion of Realism”. The public rushed to see the show, mostly to mock the avant-garde works, though a few went to defend the audacious artist.

Courbet’s brazen rejection of the academy set the precedent when, in 1863, an overwhelming majority of the entries to the Salon were rejected by the jury. The rejected artists, including Edouard Manet, James McNeil Whistler, and Henri Fantin-Latour were outraged at what they saw as a symbolic rebuff of modern art by the French state. The artists launched a protest that eventually reached the Emperor Napoleon III. In a wry move of public relations, the Emperor extended an olive branch to the offended artists and offered them their own exposition, so the public could judge the works for themselves.

Parisians flooded the Palais d’Industrie to get a look at the works on display at the Salon des Refusés, which reportedly received over a thousand visitors a day. Like Courbet’s Pavilion of Realism, while some of the public was there to appreciate the daring artwork, many came simply to laugh at the works they saw as crude and unfinished.

Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass (also called The Bath) was one of the most talked about pieces in the exhibition. Though Manet references classical masters such as Titian, Raphael, and Giorgione, the public was scandalised by the female figure’s nudity and brazen gaze. The author Emile Zola greatly admired and defended the work, later writing about it in his book The Masterpiece. Marcel Proust also mentions the painting in Remembrance of Things Past.

The state held several more Salon des Refusés over the years, but none evoked such an emotional response as the first. Edouard Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass, though misunderstood in it’s own time, has since become one of the artist’s most well-appreciated works. Keep that in mind next time you walk around a contemporary gallery…

More importantly, however, was the move towards the democratisation of art. Though the Paris Salon had long been a public event, every work had been hand-selected by the Academy. By letting rejected works be seen and judged by the public themselves, the Salon des Refusés opened up a new level of discourse between artist and spectator.

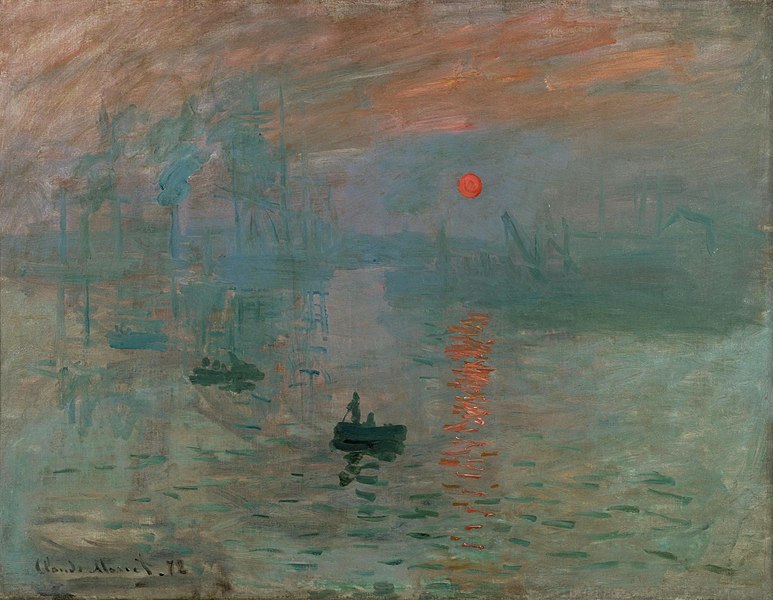

Around a decade after the first Salon des Refusés, a group of artists who called themselves the “Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, Printmakers, etc.” held a private show that took the idea of the Salon des Refusés a step further by completely severing any official connection to French artistic power structures. The show gave the group their name – the Impressionists. The movement would perhaps never have been feasible had it not been for Courbet’s Pavilion of Realism and the Salon des Refusés.

With time, more groups of artists held their own shows, including the Salon des Indépendants (still holding shows today) and the Salon d’Automne. In 1881, the French government relinquished responsibility for the original Paris Salon, turning it over to a collective of artists who called themselves the Société des Artistes Français. The group is still holding a yearly salon every February in the Grand Palais.