One of the most heartbreaking cultural losses of the conflict in the Ukraine is the Ivankiv Historical and Local History Museum, which Russian forces burned down. Most notably in the Kyiv collection are 25 works by Ukrainian folk artist Maria Prymachenko, who garnered international acclaim for her decorative paintings honouring her country’s heritage. We’re taking this moment to showcase Prymachenko’s immense talent and how she brought Ukrainian culture to the global art world.

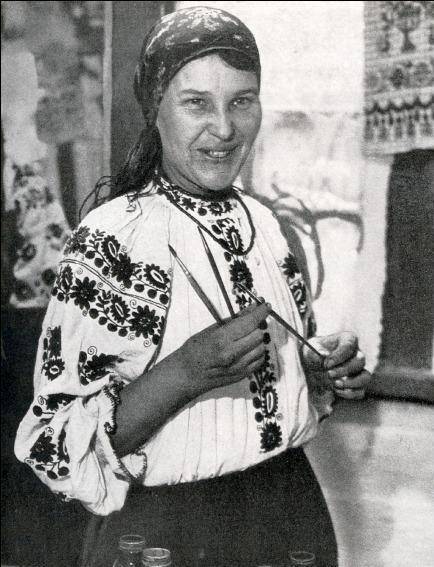

Born in 1909, Prymachenko spent her whole life in the small village of Bolotnya, only 30 km from Chernobyl. At a young age, she suffered from polio, resulting in physical disabilities that would impact her art and life path. A self-taught artist, she was inspired by the nature around her and would paint the walls of her family home using natural pigments. Prymachenko was also talented at embroidery, a craft she picked up from her mother.

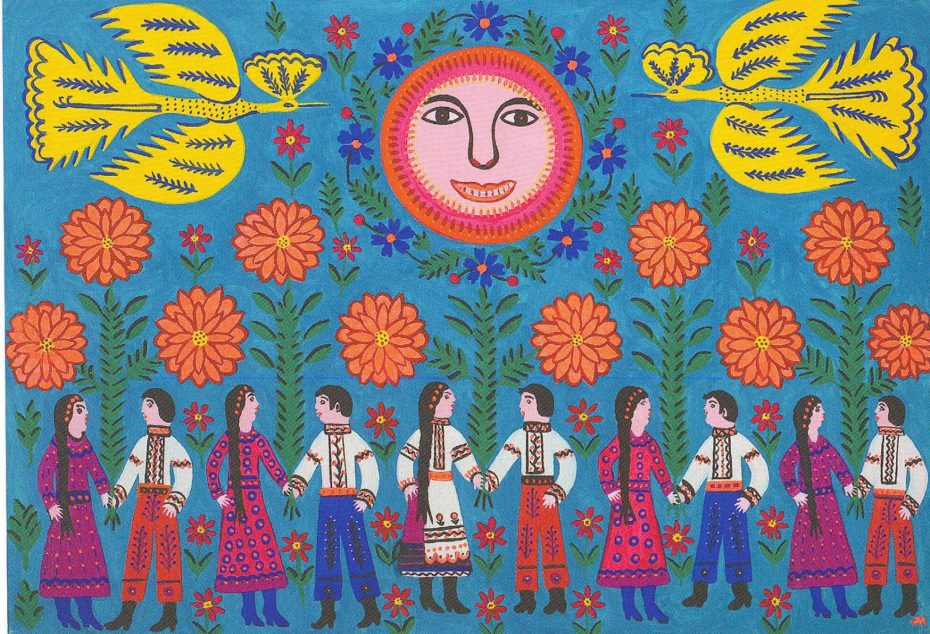

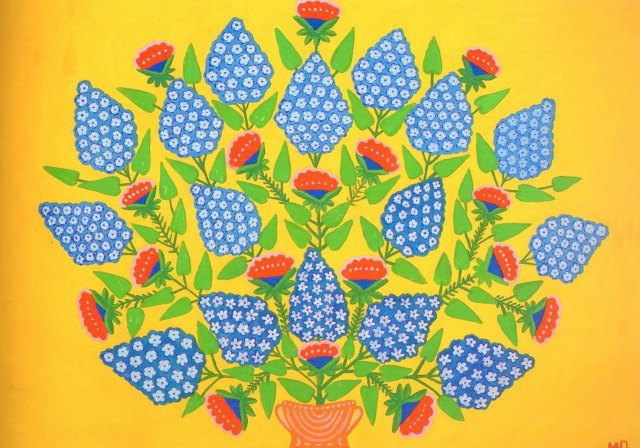

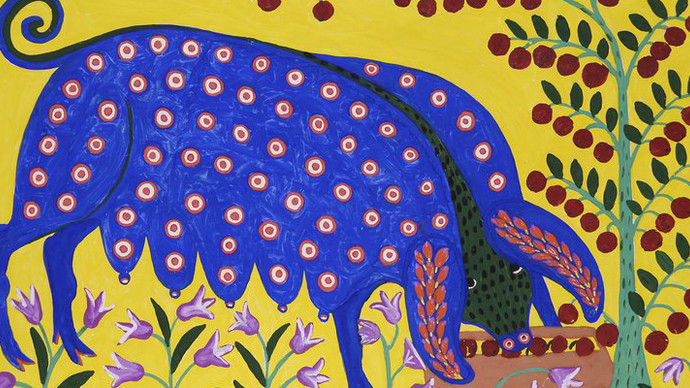

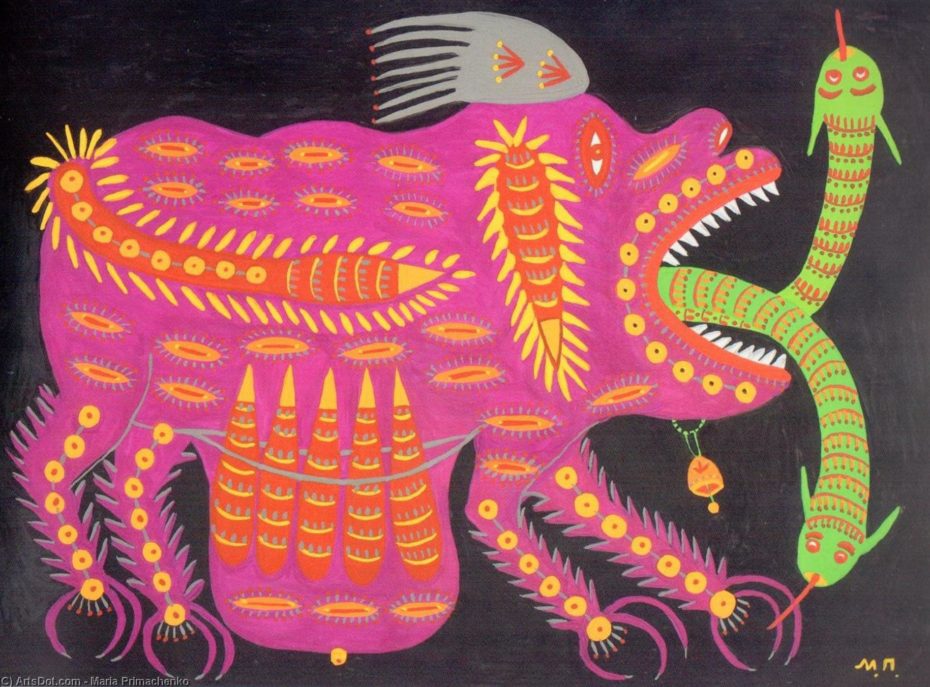

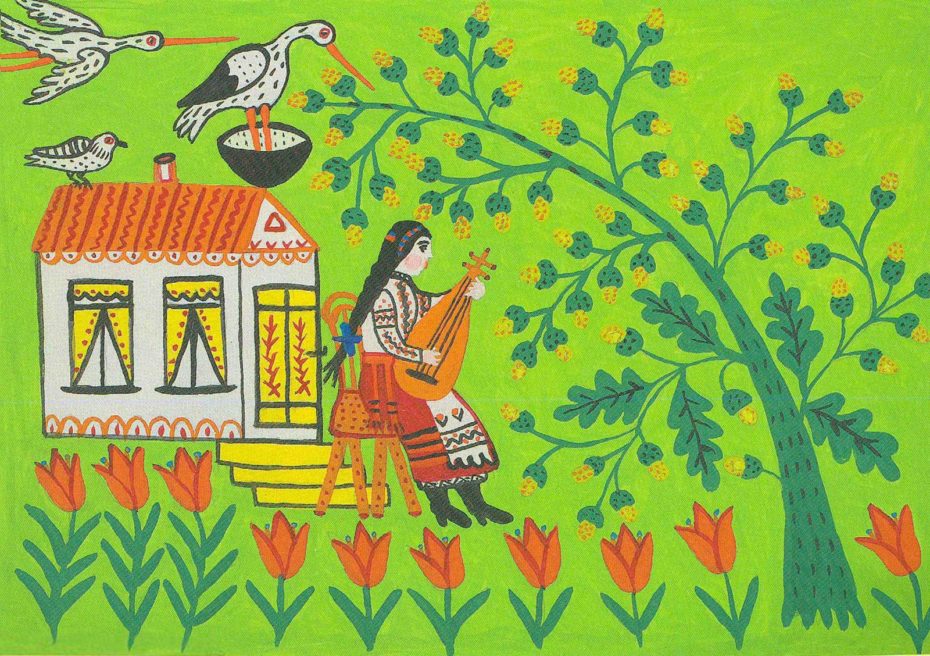

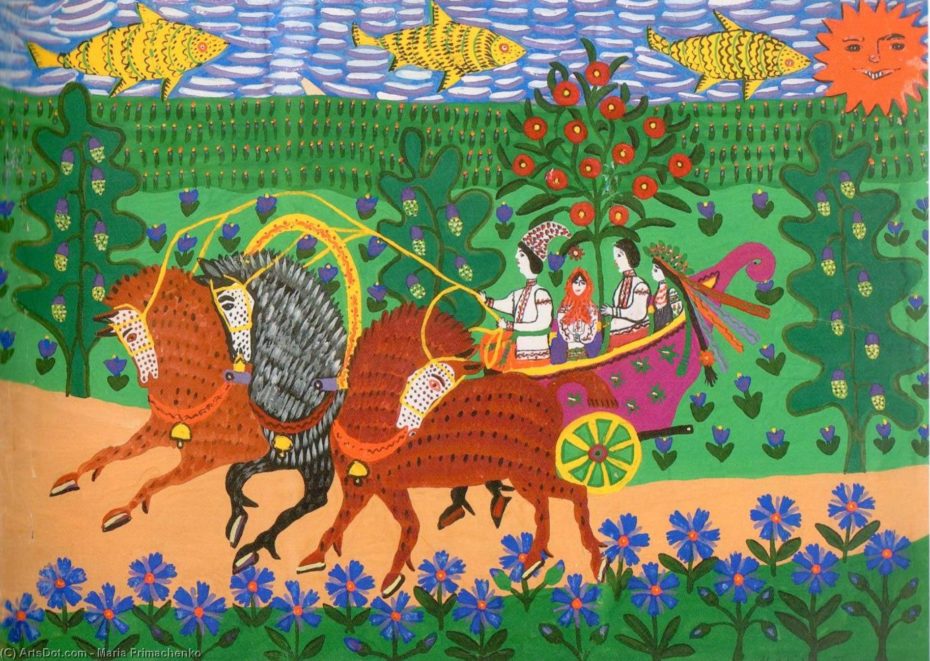

During the 1930s, she transitioned from embroidery to painting. She was particularly inspired by folk tales from Polesia, a forest area encompassing Eastern Europe, and developed an individual style, relying on bold lines and bright colors with animal, human and plant imagery. The objects are drawn in a traditional two-dimensional style, placed in both everyday domestic and landscape scenes as well as fantasies like a corn cob horse in outer space or a bear walking to go have some flour milled. Her work may fit within what’s been labelled as naïve art (not professionally trained), but these designations underscore her vision and influence.

One of her early showcases was the 1936 First Republican Exhibition of Folk Art, which traveled around Moscow, Leningrad and Warsaw. The following year, she had her work displayed in Paris for the first time (at the International Exhibition), garnering much praise. Upon seeing her work, Pablo Picasso reportedly said, “I bow down before the artistic miracle of this brilliant Ukrainian.” She found a fan in fellow Eastern European artist Marc Chagall, who also included realistic and fantastical animals in his paintings, describing them as “the cousins of the strange beasts of Maria Prymachenko.”

While in Kyiv, undergoing operations to allow her to stand without mobility aids, she met her partner Vasyl Marynchuk. They had a son, but not enough time to get married before the onset of World War II and sadly, Vasyl died in the conflict. The war years were difficult and Prymachenko worked on a collective farm with little time to make art.

Maria began to paint again in the early days of the Soviet Union and never stopped evolving during her 60+ year career. Starting in the 1960s, she switched from painting with a white background to colour. Further adding more vibrancy to her work, she shifted from watercolours to gouache. She also experimented with adding proverbs and other short phrases to her art.

During this Cold War period of nuclear armanet, her art also took on an overtly political tone. In the 1978 work “May That Nuclear War Be Cursed!” a serpent-like creature slithers from the mouth of a vicious beast. Her work has also been included in exhibitions of art connected to the 1986 Chernobyl disaster. Or there’s “A Dove Has Spread Her Wings And Asks for Peace,” a 1982 work that’s particularly poignant in this moment. Along with these expressions of struggle, she also portrayed times of hope and joy, particularly wedding scenes with couples often wearing vyshyvanka, the embroidered shirts that are part of the national costume of Ukraine and Belarus.

What connected all of her work was a desire to preserve Ukrainian heritage despite the efforts of outside forces to squash its independent identity. In a portrait of the writer and political figure Taras Shevchenko (who died in exile in Russia), Prymachenko imagines him finally being able to return to his homeland, surrounded by a flowering countryside. The image echoes one of Shevchenko’s poems, which opens, “When I die, let me rest, let me lie amidst Ukraine’s broad steppes. Let me see the endless fields and steep slopes I hold so dear.”

And clearly, Ukraine was proud of its world famous painter, putting her work on postage stamps and awarding her the 1966 Taras Shevchenko National Prize (the nation’s highest prize for cultural and artistic works). Ukrainian astronomer Klim Churyumov even named a minor planet after her. And Prymachenko’s death in 1997 didn’t end her family’s artistic legacy. Her son became an artist and like his mother, mastered the naiveté style; his two sons are also working artists. Her grandson Petro Prymachenko recalled being raised by his grandmother in a 2015 interview. At the time, he had taken a break from painting to aid Ukrainian forces in the conflict with Russia.

“Sometimes she would give me a used paintbrush to draw,” he said. “She thus taught me a little. I can also remember that a lot of people kept coming to visit my granny throughout my childhood. Among them were all kinds of artists, diplomats, ambassadors. Ordinary people were also coming often, for they all loved her so much.” Luckily Prymachenko’s prolific output means that only a small minority of her paintings were destroyed, with close to 650 of her works (dating from 1936 to 1987) being held at the National Folk Decorative Art Museum in Kyiv. But during this moment of immense suffering and uncertainty about Ukraine, there’s something comforting in turning to the work of an artist who imagined a more peaceful and prosperous future for her country.