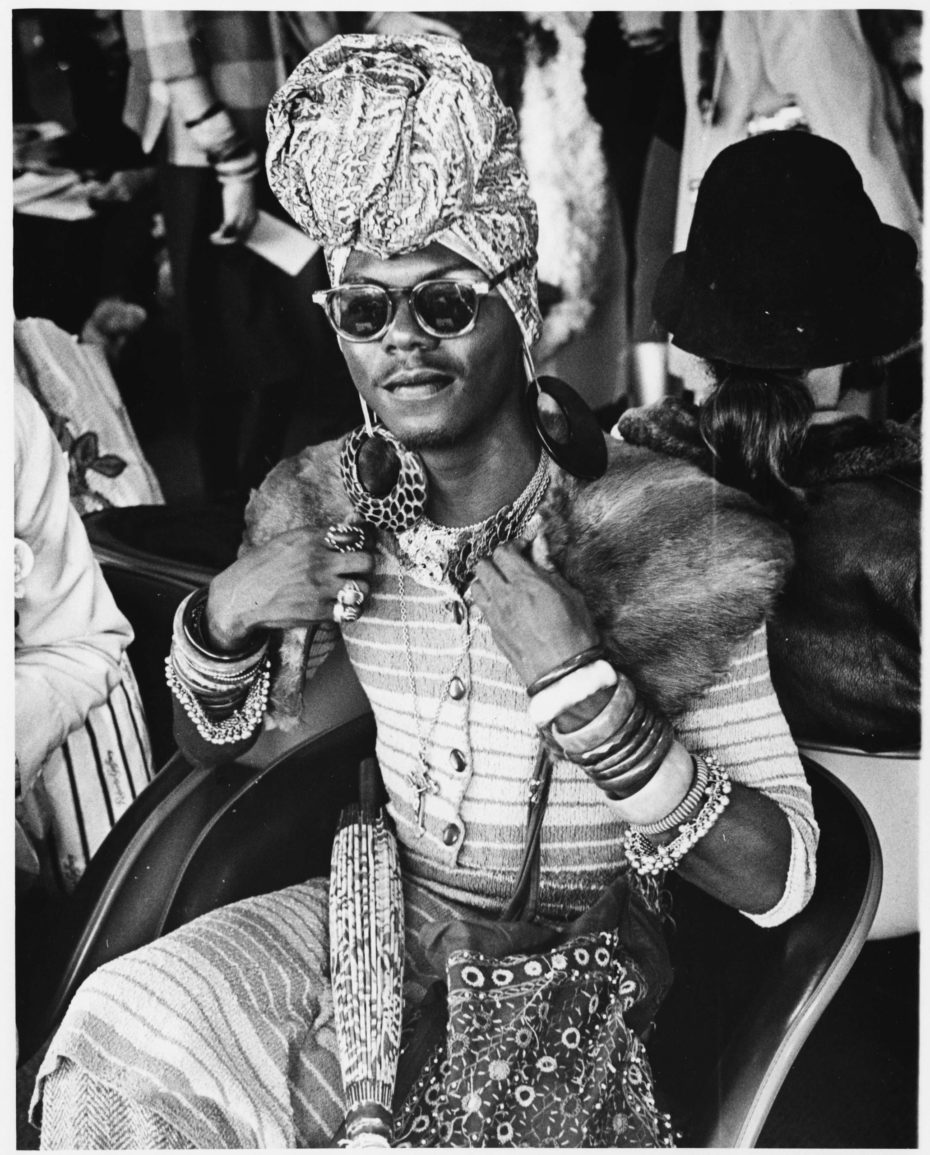

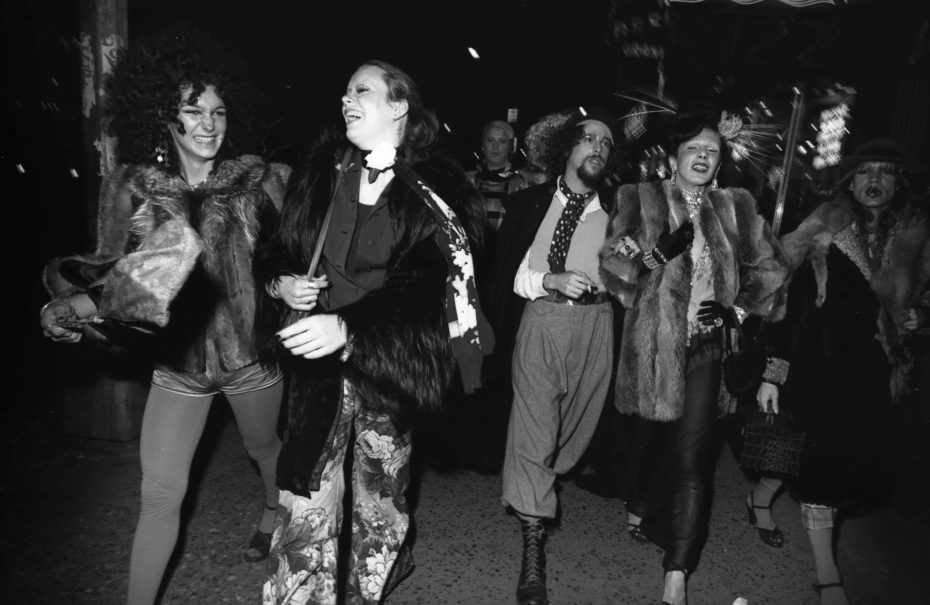

Photo by Ingeborg Gerdes

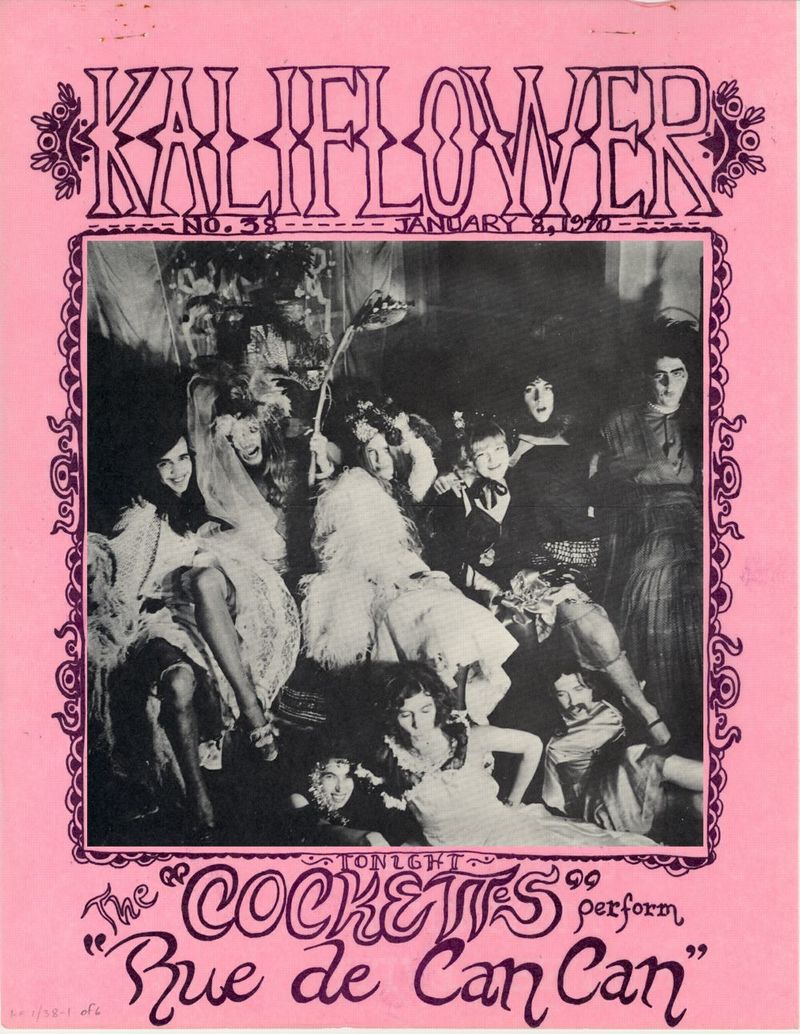

On New Year’s Eve in 1969, drag as we know it came kicking and screaming into the world. Just before the midnight movie at the Pagoda Palace, the raucous sounds of Offenbach’s can-can crackled over the speaker system. Out sprang a chaotic kick-line of queers in ragged vintage dresses with glitter in their beards and feathers in their enormous bouffant hair. When the shrieking and hollering audience wouldn’t let the troupe off the stage, the programmer played the Rolling Stone’s Honky Tonk Woman. The only possible response to that sexy syncopated baseline is a striptease. Off came the trashed prom dresses and layers of crinolines until there was a gyrating pile of glittery nude bodies joined by ecstatic audience members. “At midnight the Cockettes came on,” remembers Scrumbly Koldewyn, “And it was officially one decade to the next.”

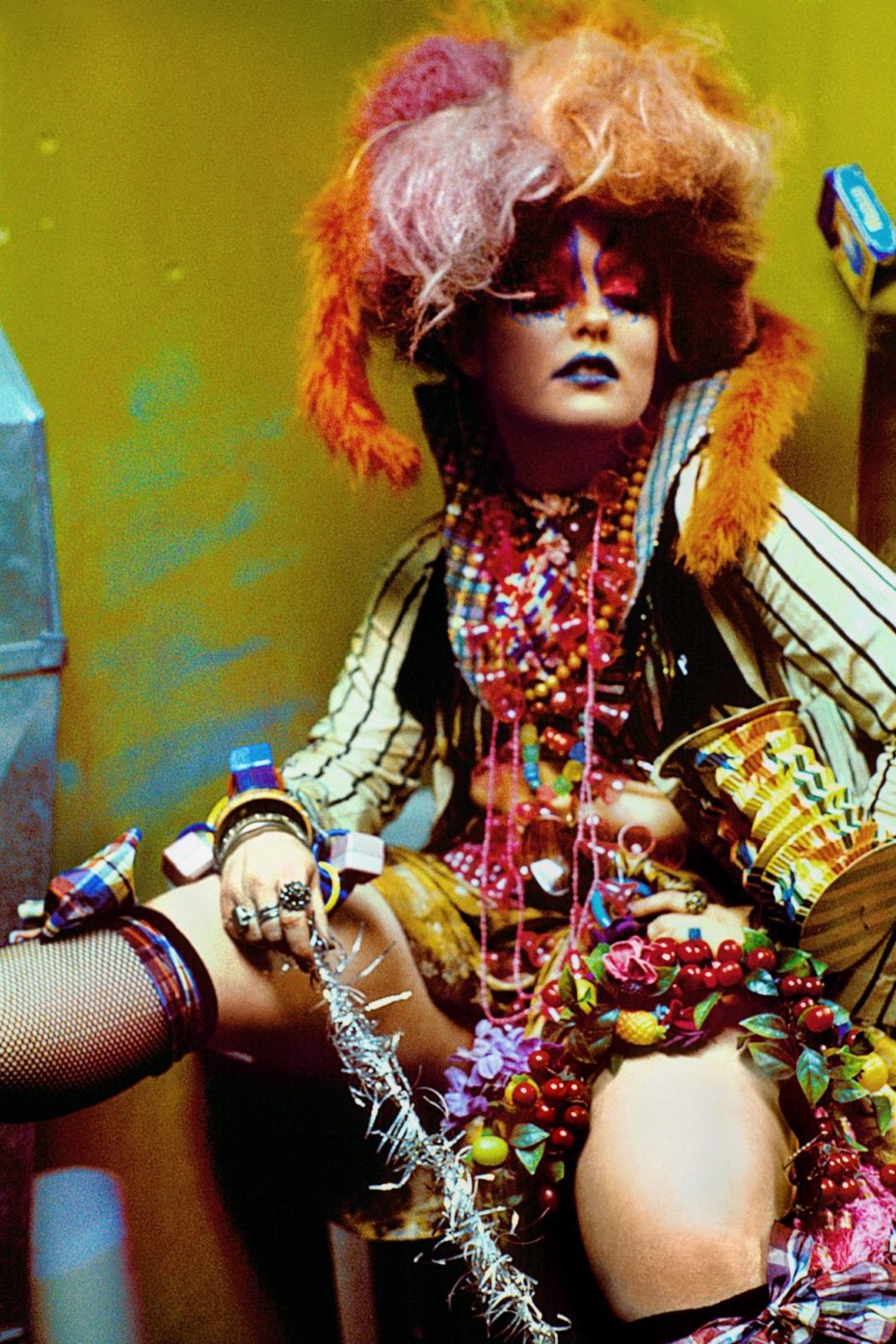

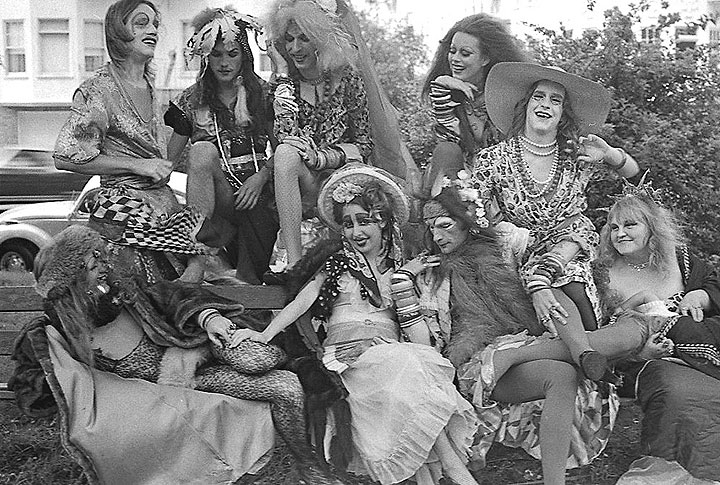

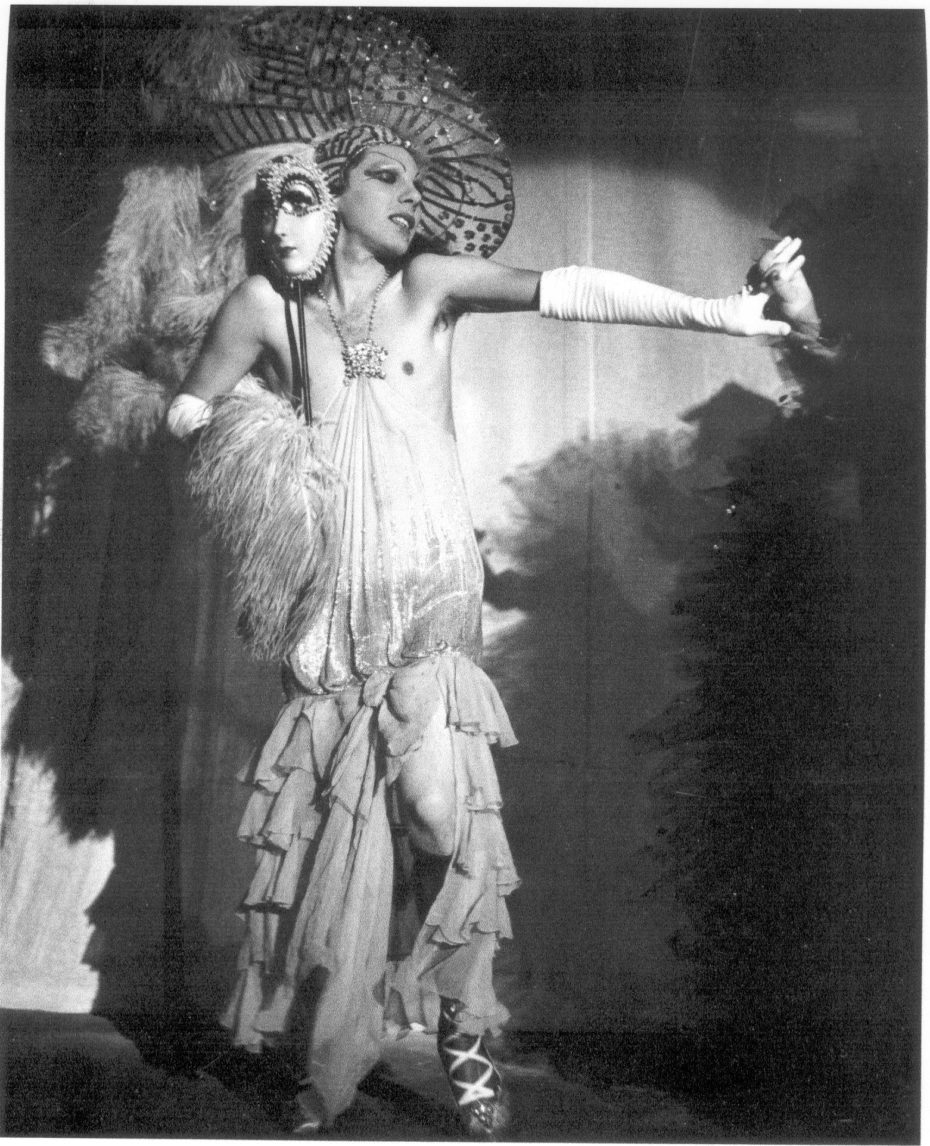

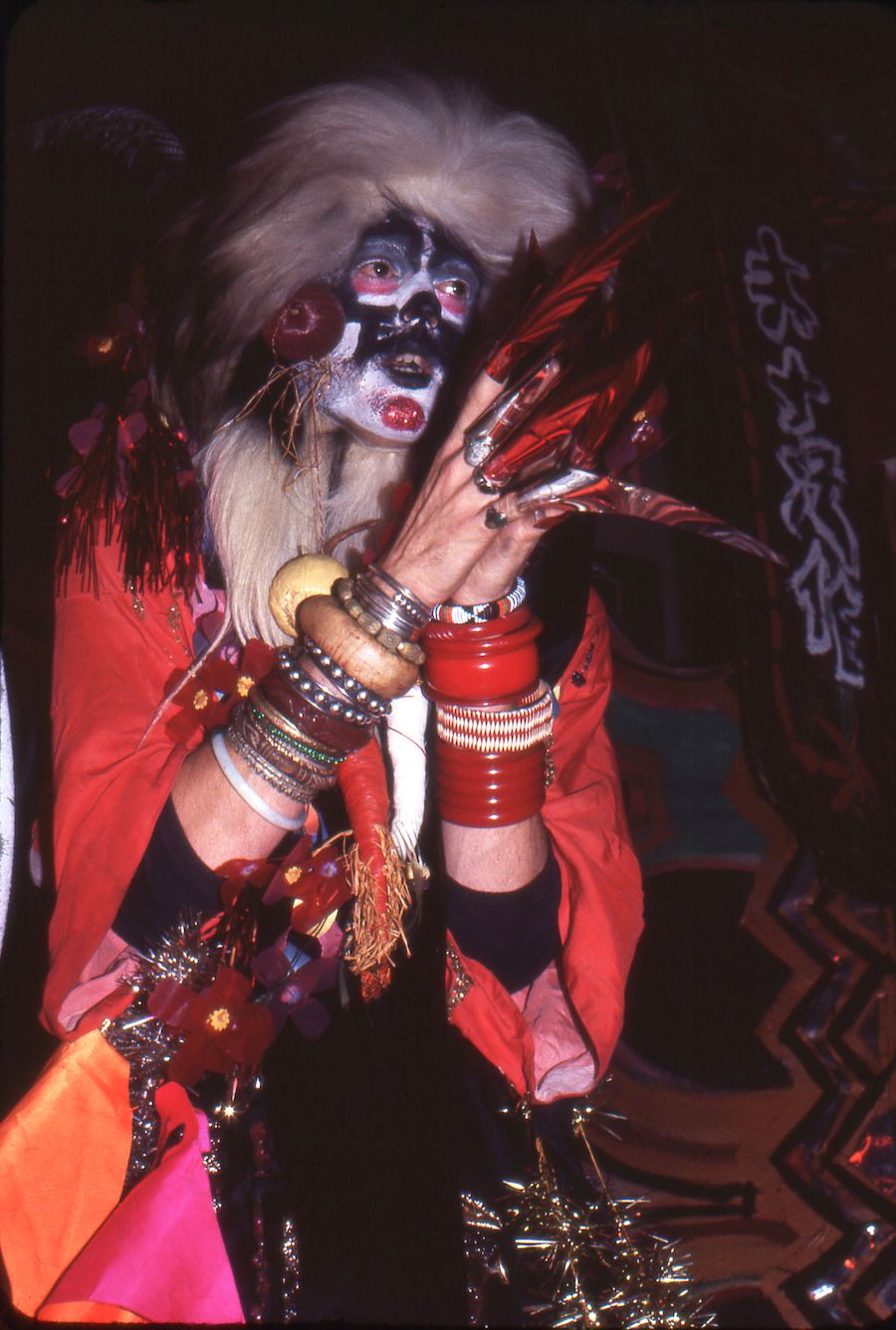

Drag has existed as long as human civilization, but before the Cockettes, crossdressers did their best to look just like ordinary women. The Cockettes, however, had zero interest in the ordinary. Subverting gender norms and synthetizing various influences, they created the maximalist style that is now the vernacular of contemporary drag performance. Big bouffant hair. White face and exaggerated makeup. Feathers and sequins. Glitter beards. Glitter lips. Glitter cocks. Glitter everywhere!

The Cockettes were the brainchild of Hibiscus, a gay hippie who was part of a communal house of acid-freak artists in Haight-Ashbury. Before Hibiscus landed in San Francisco, grew out his hair, and donned pineapple bras, he was George Harris III, the eldest of six children in a family of performers. Like an avant-garde Brady Bunch, the family started off putting on plays in their Florida garage before they hit New York City and found a home upstairs of La Mama ETC, one of the epicenters of the new Off-Off Broadway movement. Harris grew up working in the 1960s Off-Off Broadway underground, imbibing camp theater at Caffe Cino and learning to coat everything in glitter at John Vaccaro’s Playhouse of the Ridiculous.

In 1967, Harris headed off to San Francisco with poet Peter Orlovsky, then the boyfriend of Allen Ginsberg. They stopped in Washington, DC to help the Yippies levitate the Pentagon and end the Vietnam War. Joining the demonstrators, they approached the Pentagon and found themselves surrounded by military police troops, rifles aimed straight at them. Without batting an eye, Harris stepped right up to the firing line and starting putting carnations in each gun barrel. Photojournalist Bernie Boston captured the moment in one of the most defining photographs of the 1960s.

Harris arrived in San Francisco a few weeks later, joined the Kaliflower commune, took an enormous quantity of LSD, and started to “live the life of an angel” as he later said. Changing his name to Hibiscus, he began flitting around in diaphanous robes, covering himself with glitter, and wearing the elaborate fern and flower headdresses that would become his signature look. Nicky Nichols, a fellow Cockette, laughs, ”He came out of the closet wearing the entire closet.”

Hibiscus soon chafed against the strict rules of the Kaliflower and drifted into another commune inhabited by artists, where he found willing cohorts for an acid-fueled avant-garde theater troupe. He began filling a bejeweled velvet scrapbook with stage ideas and inspirational images – 1920s sheet music, Victorian postcards, Christmas angels, stills from old Hollywood films.

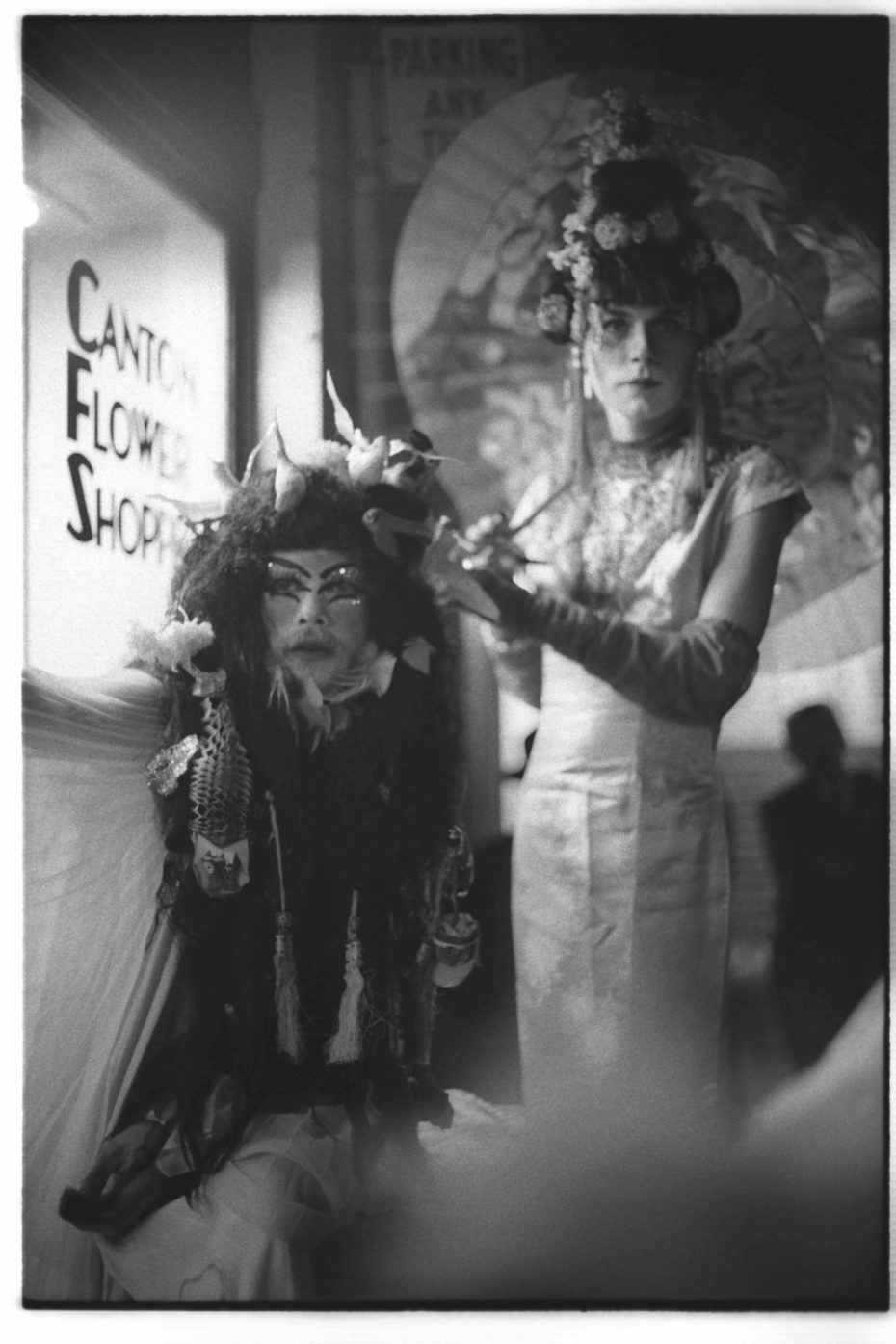

Around this time, Steven Arnold, who programmed the midnight shows at Pagoda Palace, a Chinese cinema in North Beach, started presenting music and skits in between screenings of cult classics. Arnold invited Hibiscus to join their 1969 New Year’s program. “We didn’t think anything would happen,” remembered Kreemah Ritz. But their kick-line was such a hit that the Cockettes were invited to return to the Palace. Their song-and-dance shenanigans soon evolved into full-length revues of jazz standards and obscure 1930s show tunes strung together with a flimsy storyline. “The Cockettes were the Little Rascals on acid doing Busby Berkeley in drag,” observed Rumi Missabu. They were the hottest show in San Francisco.

Like much of gay hippie San Francisco, they were predominantly white middle-class men searching for deeper meaning in life. Besides Hibiscus, there was Wally, another young man with a penchant for glitter beards and faux-Ecclesiastical mylar gowns. Other disaffected young white men included Goldie Glitters, Rumi Missabu, Kreemah Ritz aka Big Daryl, and John Rothmuler.

But the Cockettes also included Cherokee-Inuit writer Link Martin, who fled a brutal childhood of orphanages and mental hospitals. He became the Cockette’s main writer and lyricist, collaborating with musician Scrumbly Koldewyn on original musicals like Pearls Over Shanghai, a kitschy take on Josef von Sternberg’s lurid Orientalia potboiler The Shanghai Gesture. There were Black Cockettes like Lendon, who ran away from Atlanta and met Hibiscus sitting in a tree in Golden Gate Park.

There were also several women in the troupe including artist and sculptor Fayette Hauser, Dusty Dawn and her baby Ocean Michael Moon “the world’s youngest drag queen,” and Miss Harlow, an original member of the Plaster Casters, the groupies who made plaster casts of rock musician’s penises.

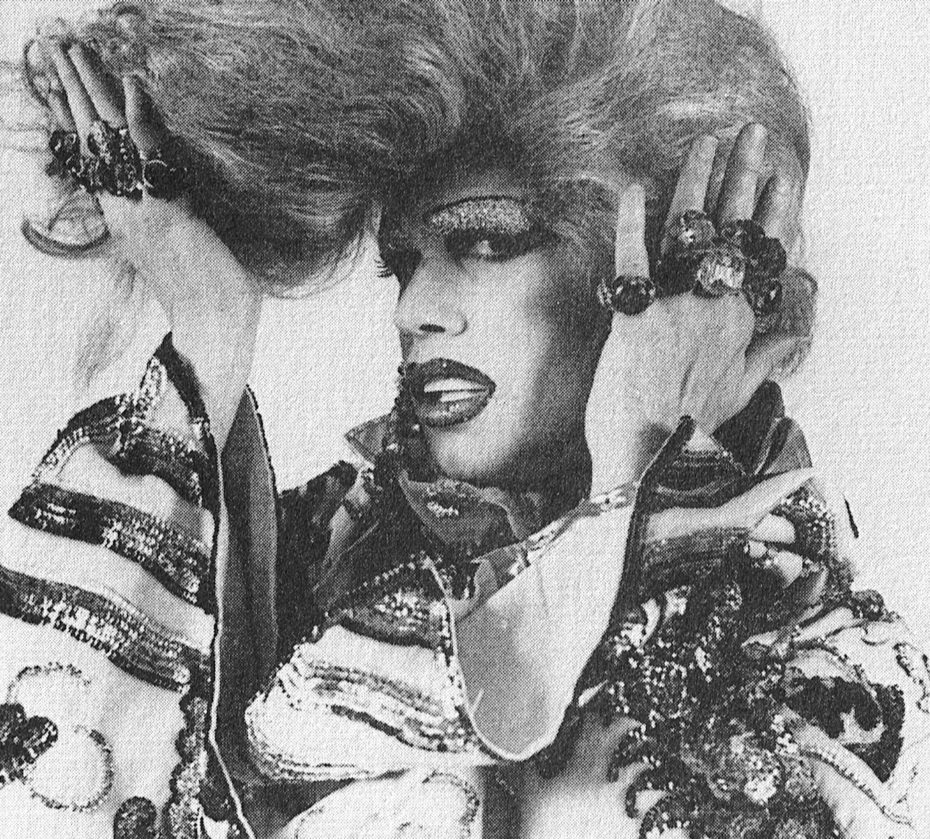

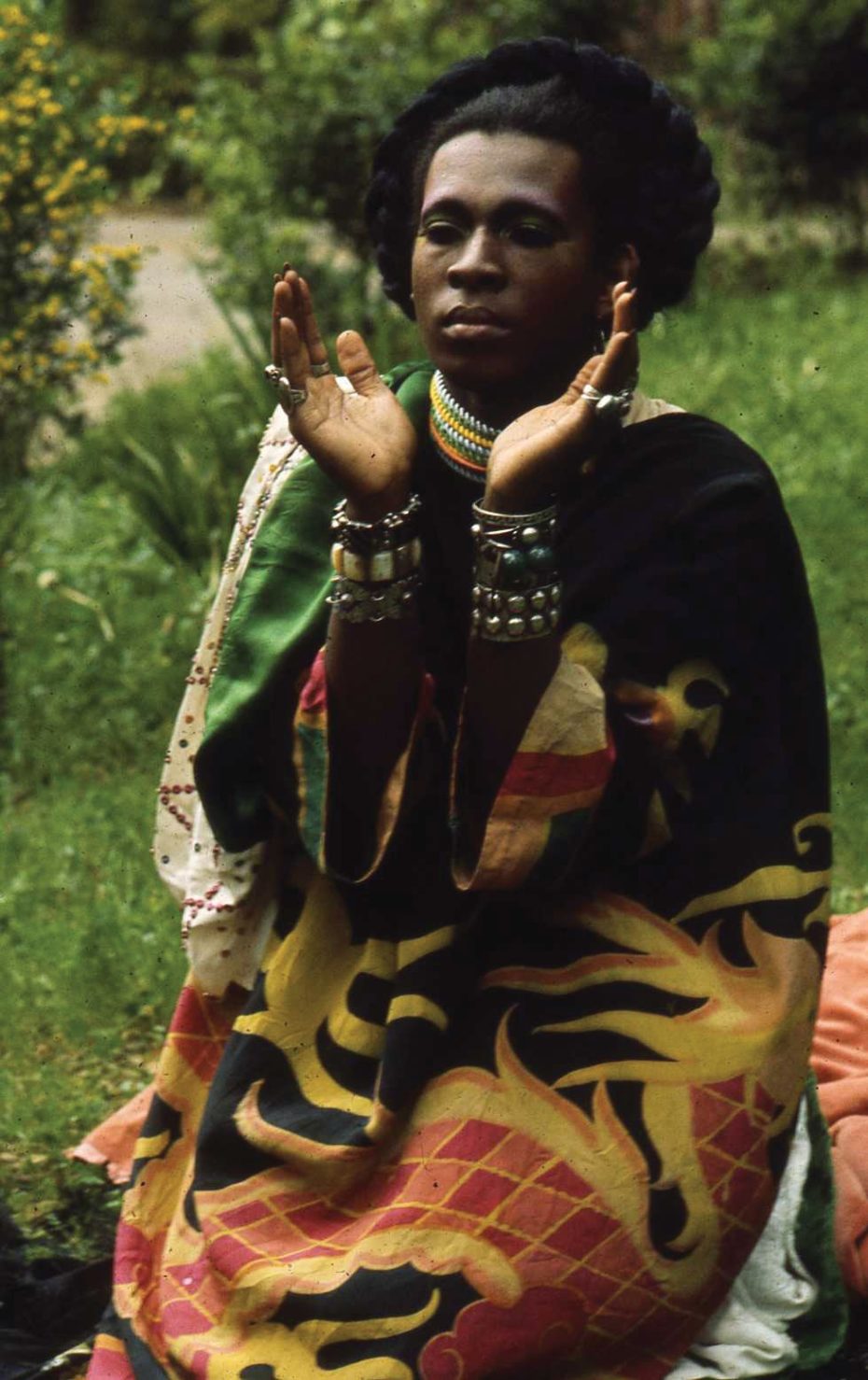

Sylvester arrived in San Francisco in mid-1970 and immediately fell in with this lot of exhibitionists, iconoclasts, and ardent amateur musical theater queens. A gifted pianist who could wail in falsetto like a 1930s jazz diva, Sylvester was in his own league and knew it.

He became the highlight of the Cockette shows. Whether it fit into the plot or not, there would be a scene in a nightclub and Sylvester would appear in a spotlight, drop-dead glamorous, channeling Billie Holiday or Lena Horne. As Soul magazine put it, Sylvester’s incandescent performances in the middle of the Cockettes’ campy chaos “were like the reverse of comic relief.”

With the success of the Cockettes came a philosophical split. Now that they were producing original musicals, many of the Cockettes were insisting on rehearsals and getting paid. Hibiscus, however, believed that theater should be spontaneous and free in every sense of the word. If a moment in a show wasn’t working, he would just don a zebra costume and meander onstage. The arguments increased until Hibiscus left with a few like-minded Cockettes and founded the Angels of Light, an explicitly political troupe committed to free shows. Hibiscus continued to produce his glittery theatrical happenings until 1982, when he died at the age of 32, one of the first hundred victims of AIDS.

The departure of Hibiscus freed the Cockettes to pursue conventional fame and success. A Cockettes wedding between Sweet Pam and Scrumbly Koldewyn was photographed by Annie Liebovitz for Rolling Stone. Truman Capote attended Tinsel Tarts in a Hot Coma and raved, “This is the most outrageous thing I’ve ever seen!” Rex Reed saw the same show and wrote a love letter in his nationally syndicated column, “They are the current sensations of counterculture show business, the darlings of the underground press, a landmark in the history of new liberated theater, and if you’ve never heard of them, some circles would say you’re just not alive.”

There was talk of the Cockettes and Sylvester performing at the Fillmore East in New York City, but nothing came of it. Then Harry Zerler, a San Francisco rock lawyer with no previous producing experience, got the backing for a three-week engagement at the Anderson Theater, a former Yiddish theater on the Lower East Side.

On Halloween in 1971, an entourage of 35 Cockettes, Sylvester, his musicians, and various partners and groupies, arrived in New York City on a cloud of media hype. Maureen Orth, a Village Voice writer who accompanied them, wrote, “During the week before opening I must have gone to 27 parties with the Cockettes, on the East Side, on the West Side, in the Village, in penthouses, lofts, museums, and basements, gotten a total of 15 hours of sleep, met two thirds of the freaks of New York, and began to suspect that all of Manhattan was gay.”

A few of the Cockettes were hip to the fact that trouble was looming. The Anderson Theater was more than double the size of the Palace and dwarfed the cardboard sets that they brought with them. There was no sound system in place, no curtains, no lights. After a round of partying, a few Cockettes would gather at two or three in the morning to try to put up part of the curtain or paint a cardboard backdrop, but most were just having too much fun. Zerler, the producer, scrounged together a sound system and it broke down during their one rehearsal.

Meanwhile, the media frenzy had whipped up a huge mob on opening night. The street was so jammed, attendees had to get out of their limousines and taxis to walk a few blocks to the theater. Drag queens dressed like Captain America and Queen Elizabeth mingled with a huge number of celebrity audience members including Liza Minelli, Angela Lansbury, John Lennon, Yoko Ono, Diana Vreeland, Jane Fonda, Warren Beatty, Andy Warhol and half of his Factory, the entire cast of Jesus Christ Superstar, and a dozen Vogue editors.

The only person who rehearsed every single day was Sylvester. Launching into an energetic 45-minute set of jazz classics and blues rock, he “had almost everyone in the house going bananas, jumping up and down like a jack-in-the-box in their seats” according to Ed McCormack in the counterculture Changes magazine.

Then the Cockettes came onstage for Tinsel Tarts in a Hot Coma and the night quickly went south. Orth summed it up in the Village Voice, “The sound system was terrible, the show was too slow to crawl, and the Tinsel Tarts were even too tired to be themselves.” Angela Lansbury stood up and said, “Let’s get the fuck out of here,” taking an entire row with her. “My God,” said Rex Reed, whose article had led to this bomb of a show, “this is worse than Hiroshima.”

After hitting the ground with such a thud, the Cockettes revived somewhat by staging their best piece, Pearls Over Shanghai, for a small but appreciative audience during the last two weeks of their engagement. Sylvester was so embarrassed over the opening night, he left after the first week. He went on to hit mainstream stardom with the disco hit song You Make Me Feel (Really Real), before dying of AIDS at the age of 41 in 1988.

The Cockettes returned to San Francisco, where they produced a handful more shows, including Journey to the Center of Uranus, featuring Divine (later known for John Waters’ films) dressed as a psychedelic crab queen and singing, “If there’s a crab on Uranus you know you’ve been loved.” In 1972, after Hot Greeks, a mash-up of Aristophanes’ Lysistrata and a 1940s MGM college football film, the Cockettes went their separate ways.

Though the Cockettes were together for less than three years, their legacy continues to be felt. John Waters notes that before the Cockettes, gay people were “kind of square.” In the wake of the troupe came glam rock, genderfuckery, David Bowie, Elton John, Prince, and The Rocky Horror Picture Show. The Cockettes captured the zeitgeist of the 1960s and heralded a nonbinary vision of sexuality that was out, loud, proud, and decades ahead of its time. “We were instant stars,” founding Cockette member Rumi asserts, “No one really cared if we could sing or dance; the fact that we dared to assume as much was enough. We evoked a vision of a bizarre utopia only to be found on the fringes of the mind, arranging the grotesque in scintillating homosexual, bisexual, asexual and quadric-sexual patterns, and decking it out in mocking rags and cock-flapping parody.”

About the Contributor