In New Orleans, stories seem to seep out of the soggy ground. Something about the heady mix of influences– African, Caribbean, Native American and French – against a landscape of backwaters and bayous creates a culture of permissiveness where characters invent the most outlandish versions of themselves in ways that would be dismissed as implausible in fiction. For the city’s most notorious turn-of-the-20th-century madam, dripping in diamonds and defiantly spinning her own ever-changing tale, that permissiveness was a resource to be harnessed and bent to her will.

Lulu White was born Lulu Hendley in 1868 in Selma, Alabama, just shy of 100 years before Martin Luther King, Jr. and other civil rights leaders marched across Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge in the fight for Black voting rights. And while her means, methods and goals contrasted starkly with those of the Selma marchers, as a woman of color White, too, defied the norms of a segregated society in a fierce and infamous bid for self determination.

Details about her early life are obscure, and that was at least partially by design: at various points in her process of self invention, White claimed to be from Jamaica and Cuba. Sometime in the early 1880s White moved to New Orleans and began working as a prostitute, throwing even her presumed birth year into question. While a 12-year-old sex worker would not have been unheard of during that period, it seems unlikely White would have found the meteoric success she enjoyed under those circumstances. By the early 1890s White was already madam of her own establishment.

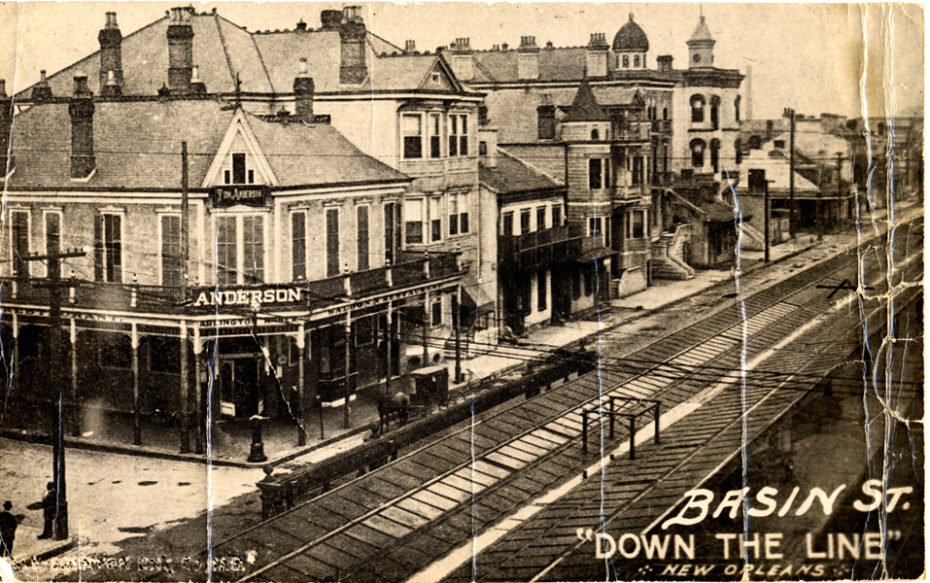

White’s rise fell on the eve of change in New Orleans. Throughout the city’s history, prostitution had been largely tolerated, and brothels operated in most neighborhoods. But as the social purity movement took hold in the U.S. in the late 1800s, reformers sought to restrict or outlaw sex work altogether. Even the city famed for letting les bon temps rouler was not immune. New Orleans alderman Sidney Story introduced an ordinance in 1897 to isolate prostitution to a 10-square-block vice district in the Fourth Ward, north of the French Quarter. His measure passed, and Story was duly horrified when the papers dubbed the new red-light district “Storyville”, forever associating his name with the brothels he attempted to restrict. But to most residents, workers and visitors, the area was simply known as “The District”.

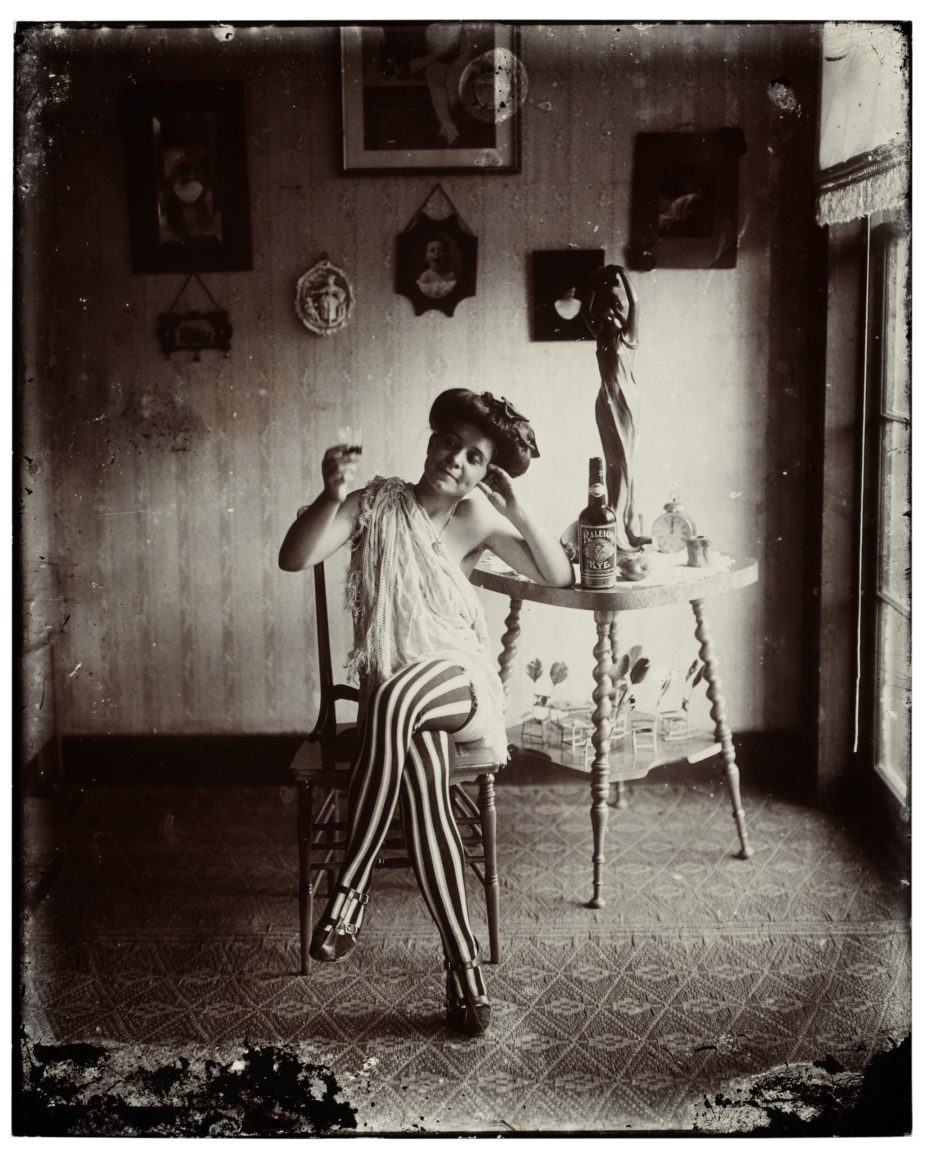

Before the invention of Storyville – full of bordellos, bars and cabarets – the area was a working-class, largely Black neighborhood. Lest we think gentrification is a new phenomenon, rents in The District rose by as much as 1,500 percent after the ordinance, forcing out many of the long-time residents. High property values might seem incongruous for a vice district, but since Storyville catered to the white male elite, money flowed through The District like muddy water through the banks of the mighty Mississippi River. And the money wasn’t just local: New Orleans was actively targeting the burgeoning winter tourism market at the time, and the entertainments offered in Storyville incited the imaginations and opened the wallets of men from all over the country. Storyville’s brothels were legally restricted to serving only white men; they could employ white or Black prostitutes but houses were required to be segregated. A nearby, unofficial district called Uptown Storyville or Black Storyville served Black men. The District included low-end establishments called cribs, crude and crowded one and two-story buildings where the women worked in shifts under abusive and impoverished conditions. But along Basin Street rose lavish and elaborately furnished mansions purpose-built to invoke the luxury they were selling.

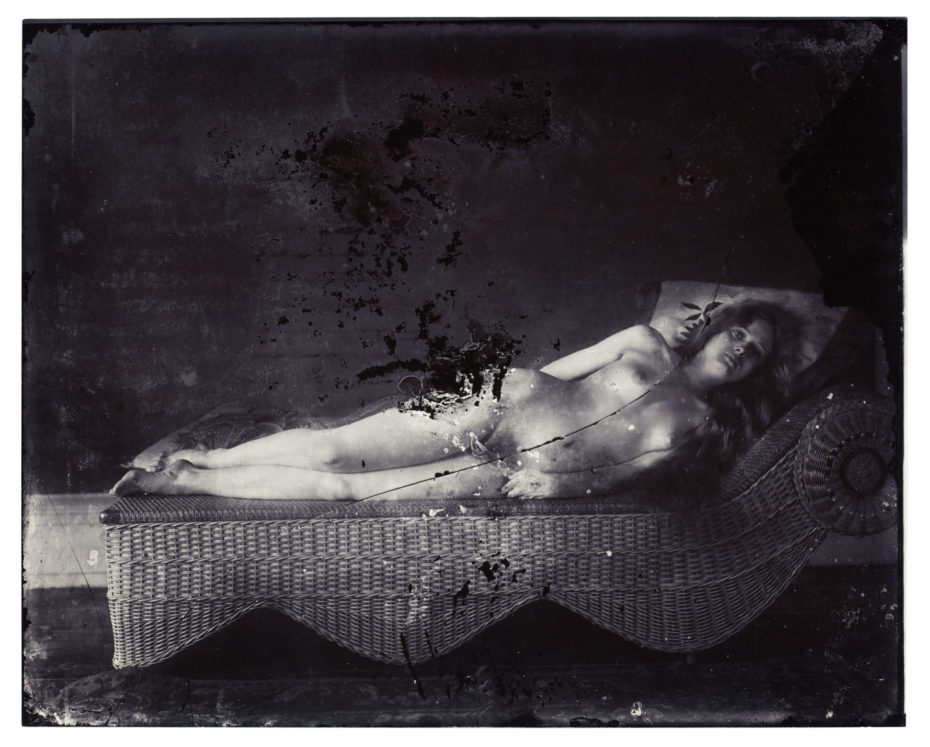

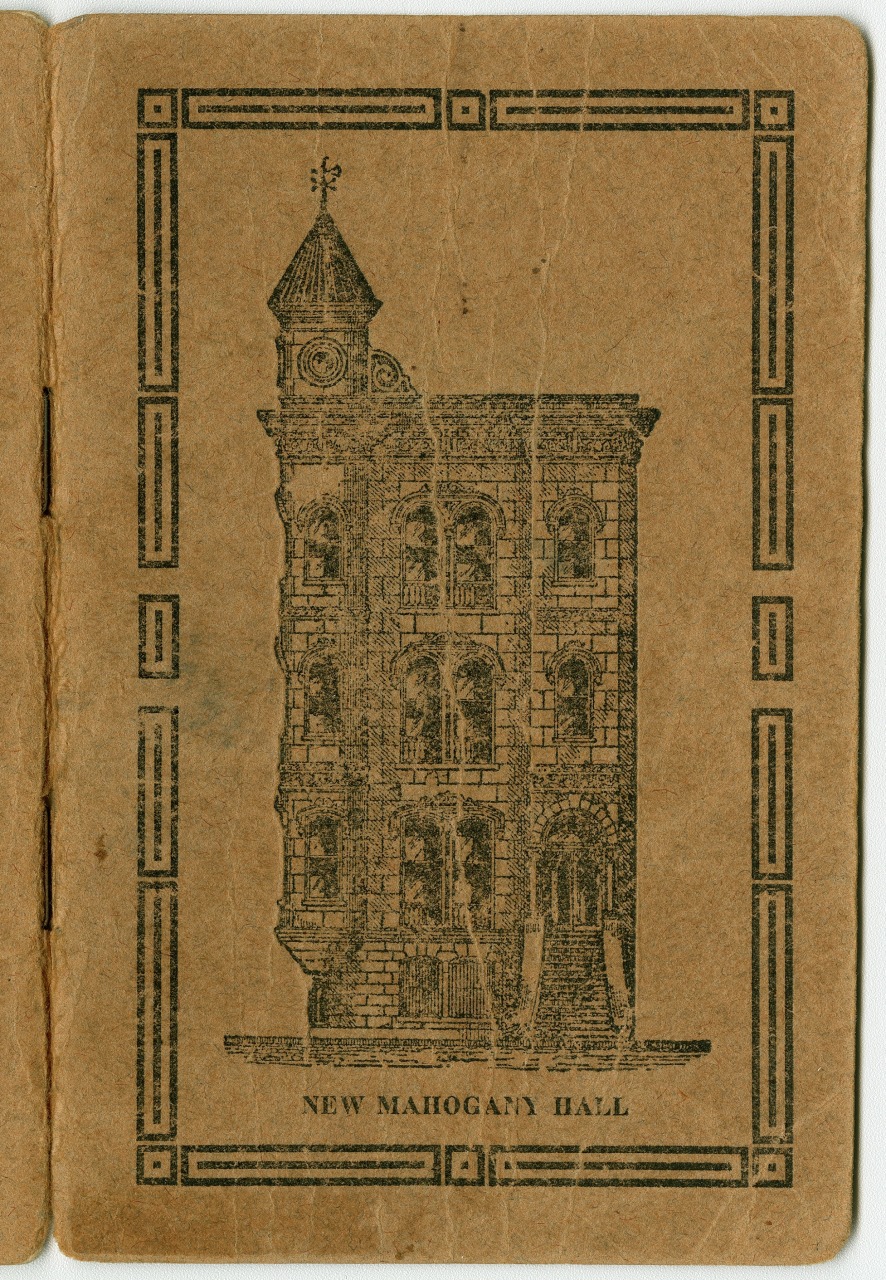

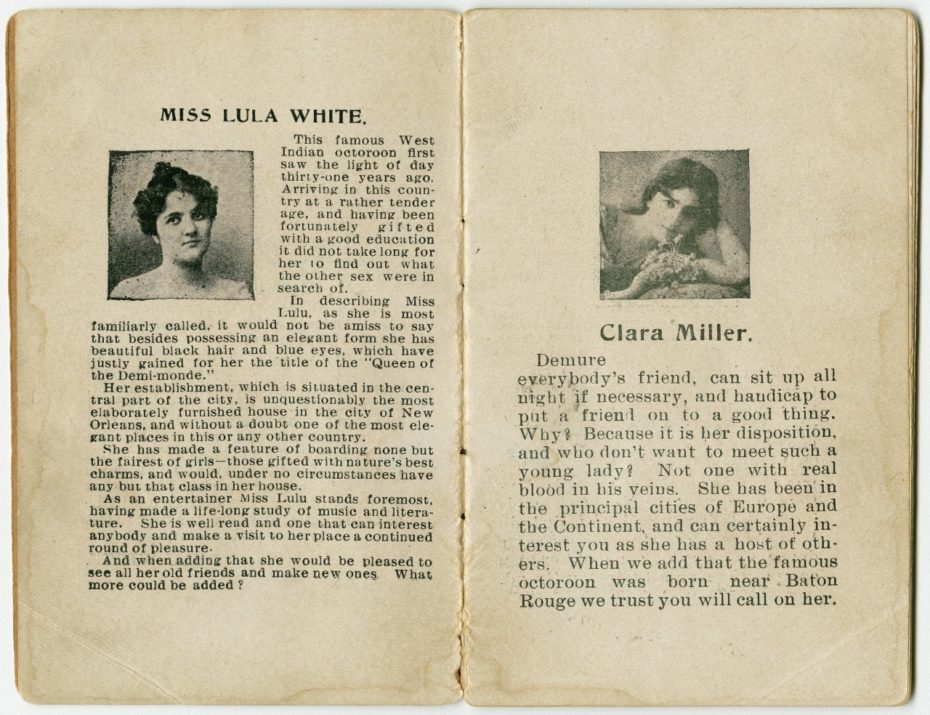

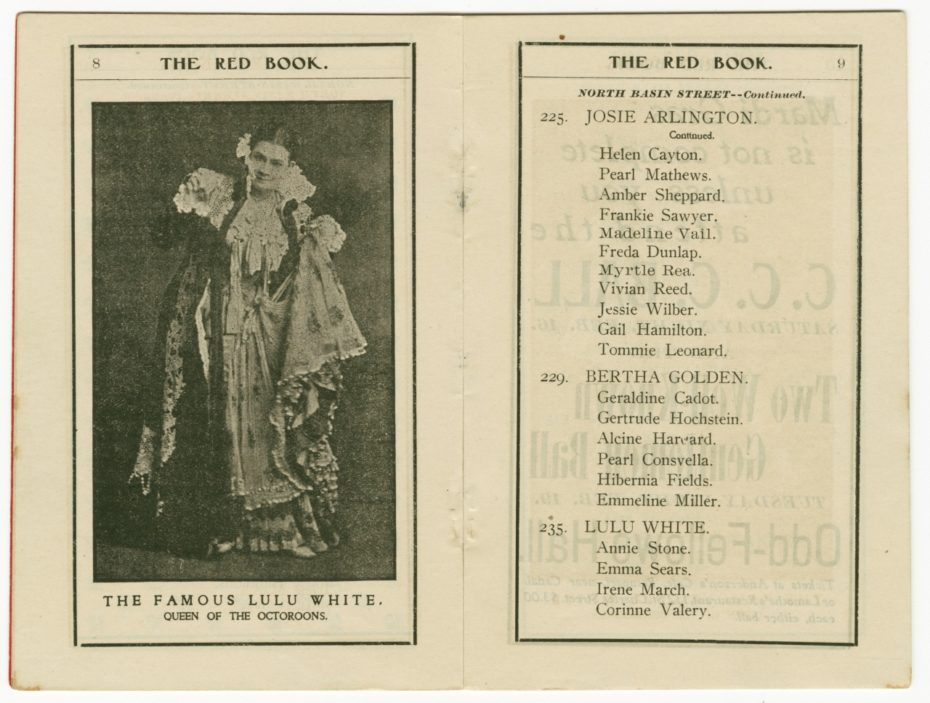

Lulu White surveyed the landscape of the newly formed Storyville and, in her own words published in a souvenir guide she produced, “having been fortunately gifted with a good education, it did not take long for her to find out what the other sex were in search of.” Shrewd and undeterred by risk, White sunk $40,000 (approximately $1.3 million today) into constructing Mahogany Hall, a four-story towered mansion at 235 N. Basin St. that featured a swirling main staircase, marble floors, fifteen bedrooms with private baths, five parlors, an elevator (built for two in the latest style, according to advertisements) and walls lined with mirrors. She arrayed herself in similar finery, earning the moniker the Diamond Queen of the Demimonde. White frequently donned a lurid red wig topped with a tiara and wore diamond rings on every finger, bracelets that climbed her arms and an emerald brooch shaped like an alligator. Of course the sparkling jewelry, ornate chandeliers and palatial furniture were just the wrappings: what White was really selling to her influential patrons was a racial fantasy repackaged for her own purposes. She christened Mahogany Hall an Octoroon Parlour–all the women of Mahogany Hall were light-skinned women of color, and White herself was dubbed the Queen of the Octoroons.

In the racialized society of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, people from multiracial backgrounds were categorized as mulatto (having one Black parent), quadroon (having one Black grandparent) or octoroon (having one Black great grandparent). From this cultural concept arose the literary trope of the tragic mulatto: a light-skinned woman with a white father and an enslaved mother who desires whiteness above all else, driven by self-loathing and only released from her misery through death. Similar tales arose around quadroons and octoroons, always centering on their ability to almost pass for white but resulting in a tragic end due to a “single drop of Black blood.” Inherent in these cultural categorisations was the assumption that though octoroon women may have possessed the socially desirable looks of whiteness, they also inherited the savagery, depravity and sexual desires falsely ascribed to Blackness. In other words, they were the epitome of sexual objects.

With the kind of marketing savvy prized today by influencers, White created a personal brand that discarded the tragedy society expected of her and instead elevated her desirability and that of the women she employed. No doubt, she was still trading in white male fantasies and upholding some harmful stereotypes, but she was also subverting the ways in which racist systems sought to keep her in her place while intentionally obstructing attempts by others to define her identity. When a segregated racetrack refused her entry, a local newspaper reported that “some people take her to be colored, but she says there is not a drop of Negro blood in her veins. She says that she is a West Indian, and she was born in the West Indies.” Regardless of the facts of her birth, White insisted on identifying as she saw herself, nothing less.

Storyville’s grand mansions offered more than just sex. Their patrons expected to be entertained for the evening, and madams were happy to oblige with dancing, singing and live music from the nascent ragtime and jazz scene. Jazz may not have been invented in Storyville, but the upscale brothels gave the genre a platform to be heard by influential men across the U.S. and provided the musicians with lucrative gigs that allowed them to continue to experiment with new sounds. Early jazz pioneer Jelly Roll Morton and Joe “King” Oliver, Louis Armstrong’s mentor, both played at Mahogany Hall. Armstrong himself grew up in Uptown Storyville, and The District’s clubs provided fertile ground for his early career. His recording of “Mahogany Hall Stomp” immortalized the feeling of exuberant nights at the famed house. While the brothels were segregated, some of Storyville’s clubs operated as “Black and tans” catering to integrated audiences with law enforcement willing to look the other way.

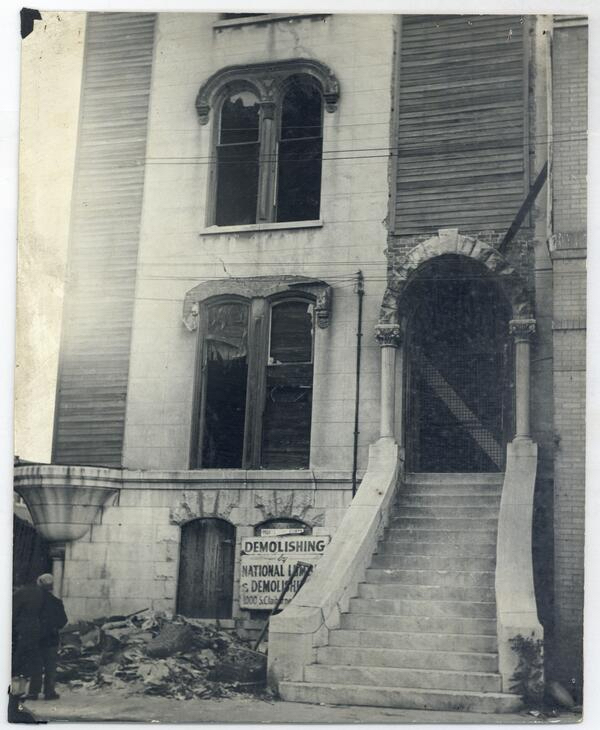

But Storyville’s shine couldn’t last forever. Twenty years after the establishment of The District, mounting pressure both from segregationists and from those who wanted a full ban on prostitution were beginning to take a toll. In 1917, legislation was proposed to officially segregate Storyville, forcing the women of color who worked there to relocate to far-less-profitable Uptown Storyville. Several madams filed suit to retain their properties and won one of the first legal victories against Jim Crow laws. But while Storyville’s madams won against Jim Crow, they couldn’t fight the Navy. As the U.S. entered World War I, anything that might distract military men from their duty was considered a threat – and that included prostitution. A federal order prohibited prostitution within five miles of any military base, and with New Orleans’s prominent Navy presence, that spelled the end of Storyville.

The closure of The District meant economic disaster for a neighborhood built on the money working girls made. It wasn’t only the brothels that suffered, but the clubs, the saloons, the music halls, the grocers and the merchants. White was among the madams who attempted to persevere in spite of the order to close. She had been no stranger to legal trouble, garnering a long rap sheet of charges spanning from assault to “stabbing with intent to murder.” But with both her influence and her money waning, her lawyers were no longer able to keep her out of trouble. She was repeatedly arrested on charges of “running a disorderly house” in violation of the closure of the brothels and after the Volstead Act of 1919, for selling liquor at her adjacent saloon. In 1929, she sold Mahogany Hall and the saloon to the owner of a local department store who reportedly used it for storage.

Much like her beginnings, White’s final act remains clouded. She is presumed to have died in 1931 while awaiting trial again on charges of running a brothel. But in a tantalizing twist, a bank teller at the Whitney National Bank in New Orleans claimed to have recognized White in 1941 as she made a withdrawal from her account. Despite the odds, it is tempting to imagine the inimitable Diamond Queen rising from obscurity and reinventing herself once again rather than meeting her end, ill and impoverished.

The former Storyville sank into poverty and was considered a slum when most of the property was purchased by the New Orleans Housing Authority for construction of the Iberville Housing Project in the late 30s. Mahogany Hall remained standing until the 40s. The first floor of the saloon is all that’s left of Lulu White’s Storyville empire. Today it operates as a corner store and restaurant.