Before Polaroids and Kodak colour, before we could snap a selfie and pass it through a colour filter with a click of a button, there was Vivex. If you’ve never heard of it, you’re not alone. The Vivex colour process was produced in just one British factory that shut down at the start of World War II. In the 1930s, however, 90% of colour photography in the UK was created through Vivex. And it was a woman who was the master of this lost technique of colour photography – Madame Yevonde – who almost singlehandedly elevated colour photography to an art.

Madame Yevonde was the professional name of Yevonde Cumbers, born in 1893 to a well-to-do family in London. Bored by her convent school in Belgium, Yevonde joined the suffragette movement during the years of its most militant direct action. Like many women, she became less active after the mass arrests and police brutality against suffragettes in 1910. That year, she interviewed for a job assisting Lena Connell, the foremost suffragette photographer. She didn’t take the job but she discovered her vocation. She wanted to be a photographer.

Intent on her purpose, Madame Yevonde contacted leading society photographer Lallie Charles. She got along well enough with Charles that she began an apprenticeship. But after two years, she had enough of demure damsels staring into a middle distance with a bouquet of flowers pressed to their bosom. On her 21st birthday, she received £250 from her father and opened her own studio, styling herself “Madame Yevonde – Portrait Photographer.”

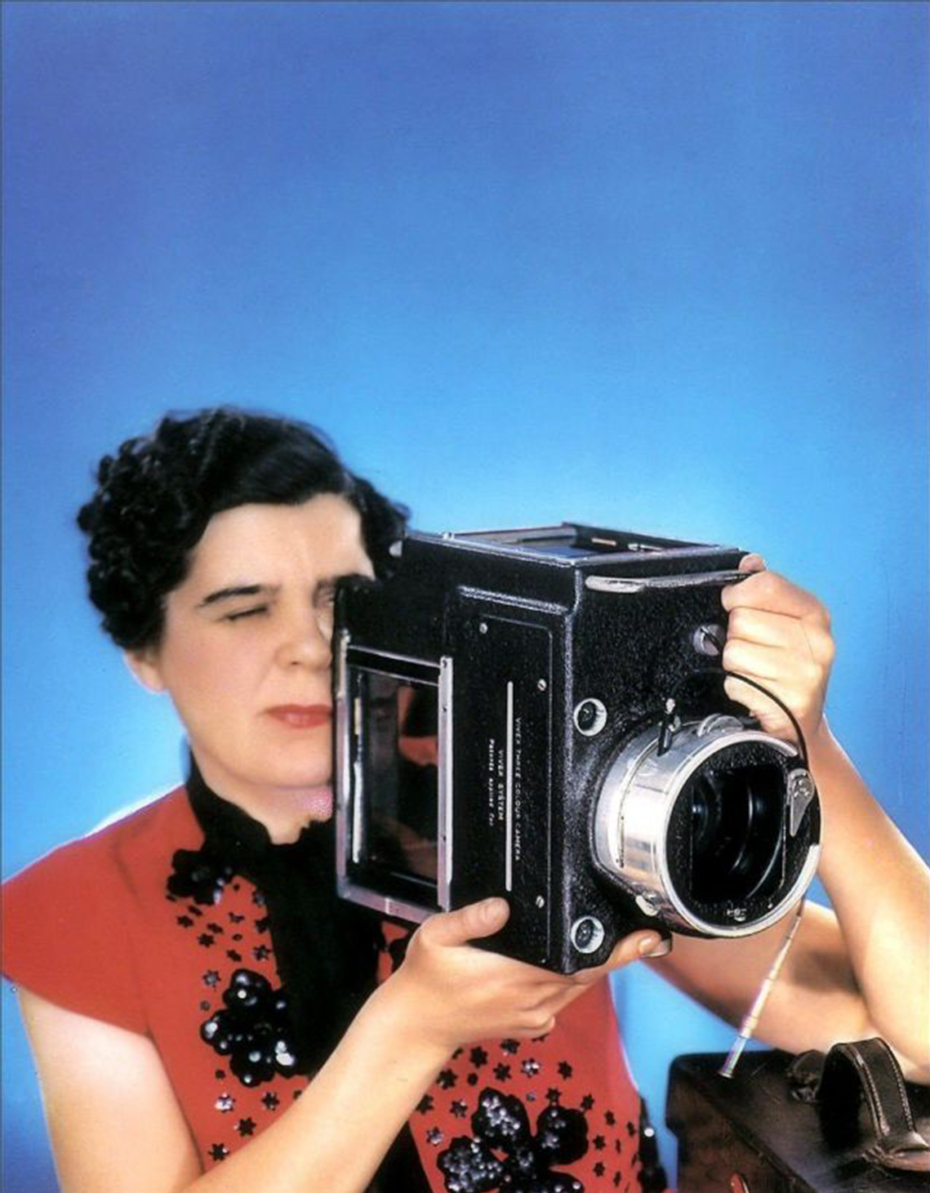

Madame Yevonde was soon experimenting with ways to break free from the portraiture that was common at the time. Her photographs were glamorous, striking, and bold. She often used props, costumes, and mirrors to add symbolism or nuance. She also mostly photographed women – actresses, society ladies, wives of foreign dignitaries. Her work appeared in Vogue, Tatler, and Harper’s Bazaar. In 1920, she joined the Professional Photographer’s Association and became the first woman invited to speak at one of their meetings. Her topic was “Portraiture from a Women’s Point of View.”

In 1930, Madame Yevonde became acquainted with the Vivex colour process, invented by research chemist Dr. D. A. Spencer. Until Vivex, colour photography had been limited to the Autochrome, a transparent colour image on glass that could only be viewed with a transmitted light source. Autochromes were beautiful but not practical. Not only were they were incredibly expensive, but the colours were so delicate that they faded rapidly and irreversibly with each exposure to light.

Vivex was a totally different technique. Three color plates for red, blue and yellow, were exposed separately. They were then developed into gelatin pigment layers and merged by hand. The negative was printed on paper, yielding permanent, vibrant, sharp photographs. Madame Yevonde was in love with the results. But colour photographs were not considered artistic. Her wealthy sitters were skeptical about them and arbiters of taste all agreed that serious photographers did not use colour. Madame Yevonde set out to prove them wrong.

She experimented with different lenses, lighting and exposure techniques. She became an expert at adjusting the three separate colour plates to manipulate the depth and intensity of the colour. In 1932, she opened the doors of the Albany Gallery in London to reveal an exhibit of 70 images, half of them in brilliant colour. It was the first exhibit of colour photographs in England. The British Journal of Photography gave her a glowing review, and commercial work came in as a result of the show, but the general public remained sceptical about the merits of colour photography. Yevonde wondered how to change this public perception.

She gave a lecture for the Royal Photographic Society in London, Why Color, using her own colour images as an example of how exciting colour could be, stating, “If we are going to have color photographs, for heaven’s sake, let’s have a riot of color, none of your wishy-washy hand-tinting effects.”

In 1935, society ladies in London were in a tizzy at the Olympian Ball at Claridges Hotel, a costumed charity gala for the blind. The theme was Greek myths and all the fashionable women in London were outdoing themselves with lavish costumes. Naturally, with all the effort they were going through, they wanted a beautiful photograph of themselves. As Madame Yevonde photographed several women before and after the ball, she had a brainstorm. She decided to create an entire series of society ladies as figures from Greek mythology, all in breathtaking colour. Cherrypicking the society ladies that she thought would be the best models, she modified their costumes and staged them to her exacting specifications. The result was Goddesses, exhibited in July that year. It was an enormous success and established colour photography as a serious medium for portraiture.

Alas, Madame Yevonde’s days with Vivex were numbered. World War II was declared in 1939. Soon after, Colour Photographs Ltd., where Vivex was exclusively manufactured and processed, shut down. Madame Yevonde was abruptly forced to stop working in the colour technique that she had perfected. The factory never reopened and Madame Yevonde never went back to colour photography. Reverting to black-and-white, she continued working as a photographer until her death in 1975.

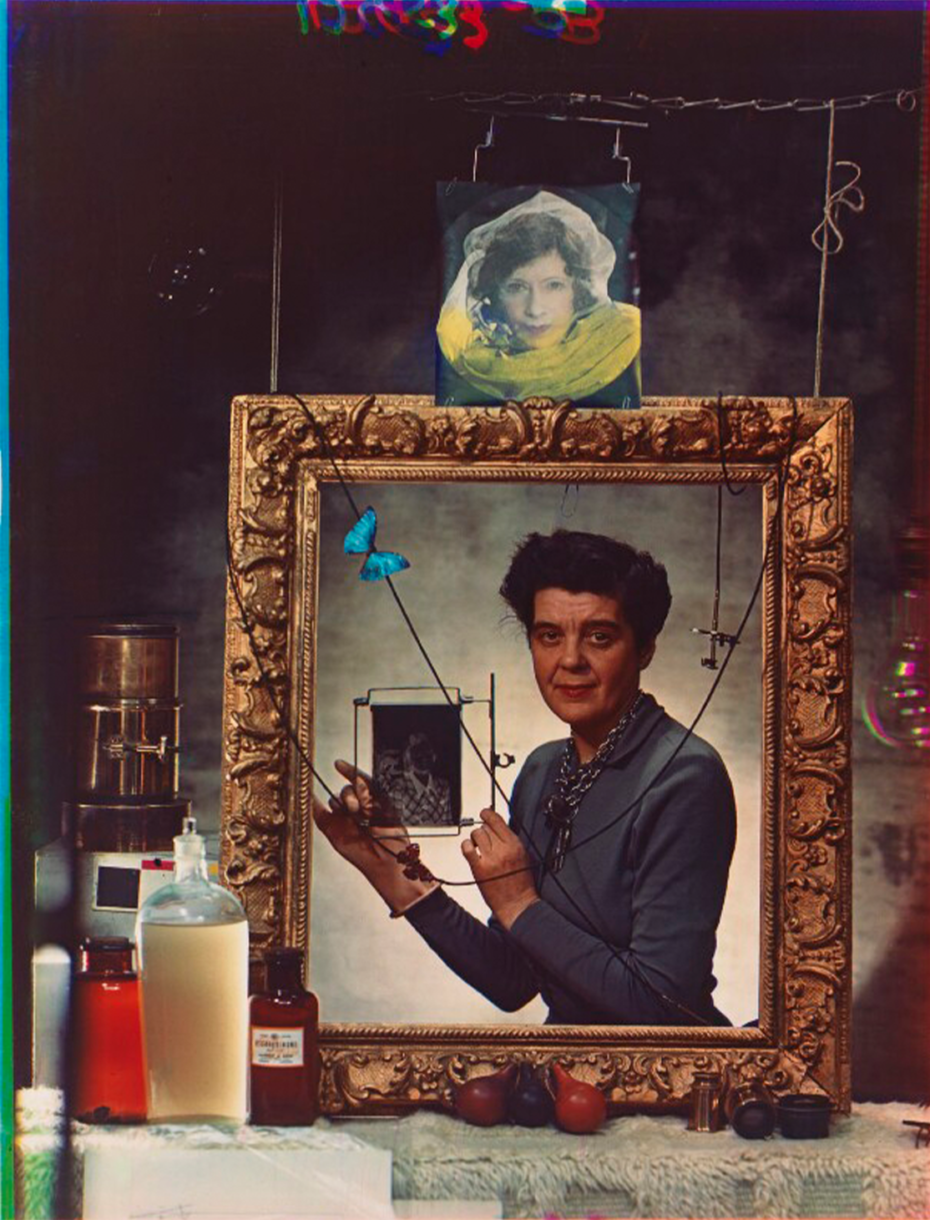

Madame Yevonde’s last colour photograph in 1940 is a self-portrait surrounded by the chemicals used in her beloved colour process. She holds a black-and-white glass photo plate with a tentative, uncertain smile. Pasted above her is one of her Goddess photographs, Hecate, the goddess of the moon, along with a blue butterfly, as if colour photographs were now forever out of her reach.

About the Contributor