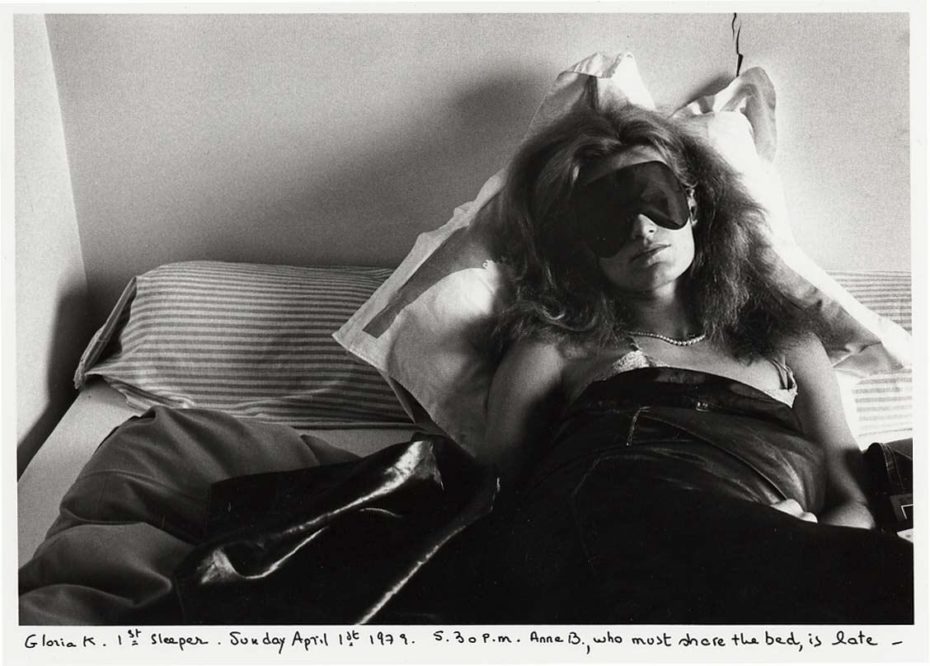

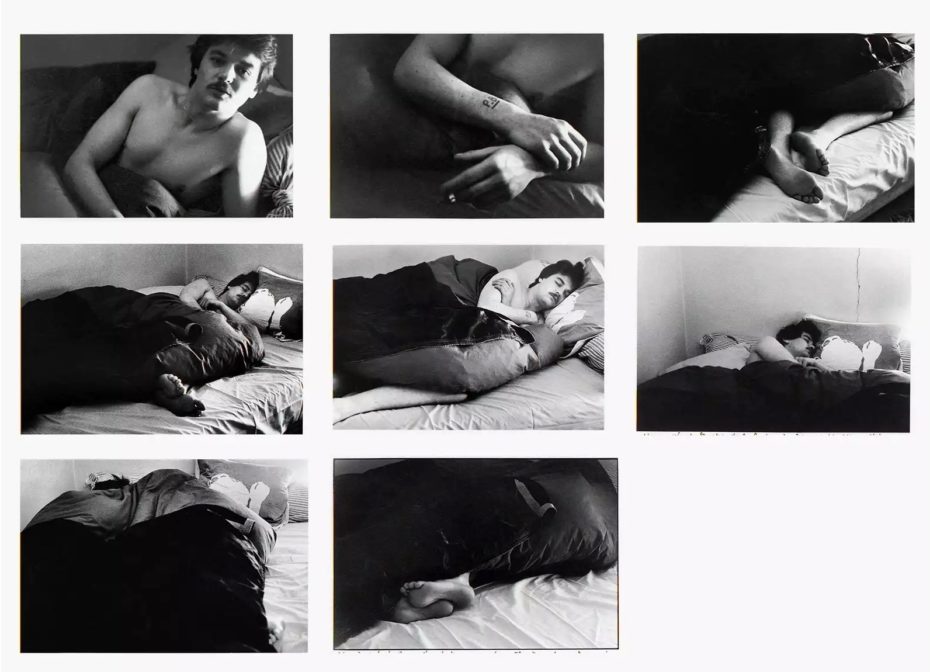

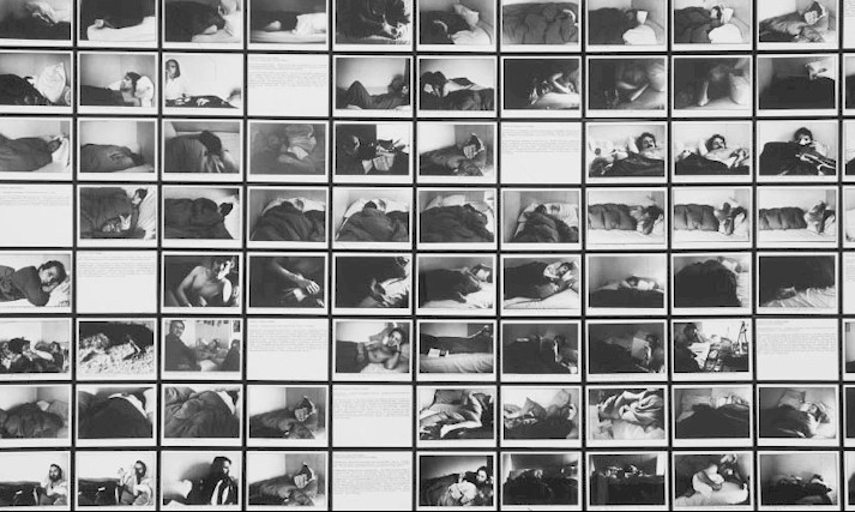

It started out simply enough. At the age of 17, the artist Sophie Calle dropped out of university where one of her professors was Jean Baudrillard – yes, the philosopher – and spent the next seven years travelling through the French mountains, then Crete, China, the United States, and Mexico. When she returned to Paris, she began what she would term ‘private games’ – games that would go on to form the basis of her career. Having been gone for so long, she started to follow strangers as a means of reacquainting herself with the city of Paris. Having never attended art school, in 1979 she exhibited her first major project, The Sleepers (1979), which involved inviting strangers to spend eight hours in her bed, documenting their stay through notes and photographs.

The intimacy of these photographs rubbed up against the clinical banality of the textual descriptions, and thus Calle began to be known by her use of portraiture, conceptual art, and the intersection of public exposure/private experience as a creative drive for her work. In amongst all this, Sophie was still enjoying her ‘private games’, still following strangers around the streets of Paris. One day, she bumps into a man she had been following earlier that day at a gallery opening they’ve both been invited to. Quelle coïncidence! Overhearing that he will be travelling to Venice the next day, she decides then and there to follow him.

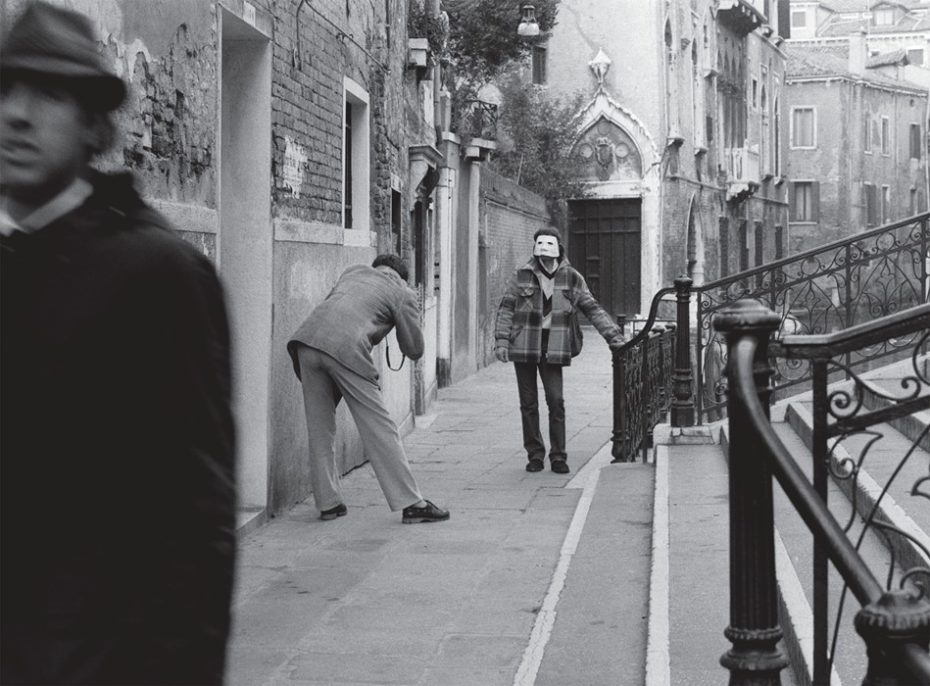

Her suitcase, as she stands at the entrance to Stazione Santa Lucia, is filled with the usual suspects; toothpaste, underwear, blonde wig, hats (various), gloves, a veil, sunglasses, etc. It is February and, in another act of coincidence, Carnevale has come to the city on the water. It is the perfect setting under which to surveil someone, and that someone is referred to by Calle as only ‘Henri B.’

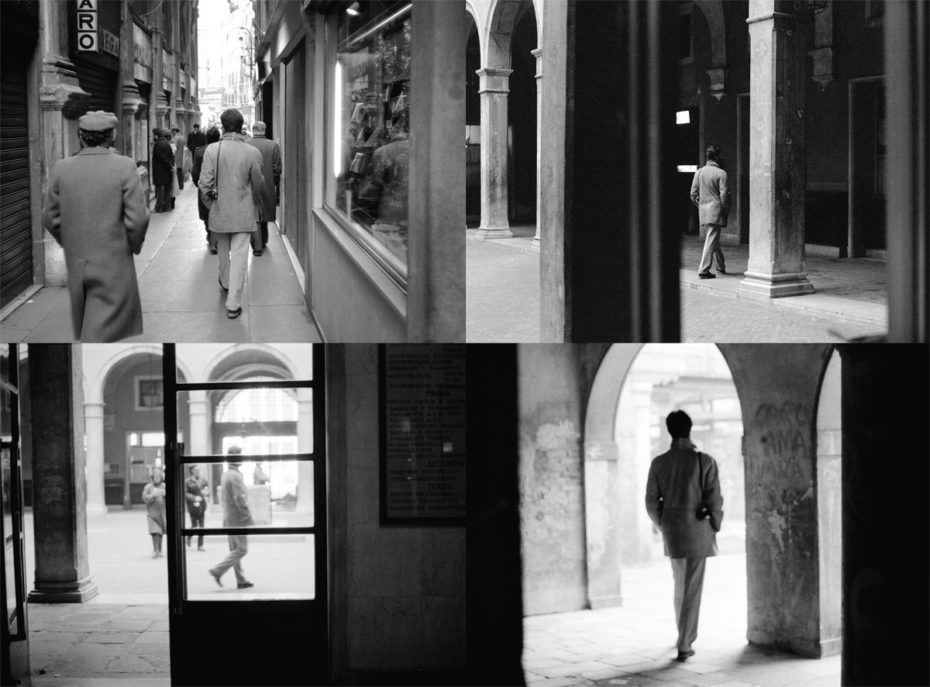

The first few days are spent actually locating Henri B., which proves difficult. Every hotel she rings – the Cipriani, Carlton Executive, Gabriella, Metropole, Luna – claim that no one by his description is a guest there. Eventually, though, she finds him at the Casa de Stefani. Then the voyeurism really begins. Henri B is travelling with his wife, and Calle follows the pair of them, noting which shops they go into, how long they spend there; where Henri, who is a photographer, stops to take a photograph. Where he stands, she stands. What he sees, she sees.

But Venice is a labyrinth, and its misdirection, shadowy corners, and foggy side canals seem to act as both accomplice to Calle’s surveillance and saboteur. Running like tentacles from the squares, there are said to be more than three thousand alleyways spreading through Venice known as calli, plural form of calle, which shares its name, in yet another coincidence, with Sophie. Some are so narrow, the poet Robert Browning noted, that he couldn’t open his umbrella.

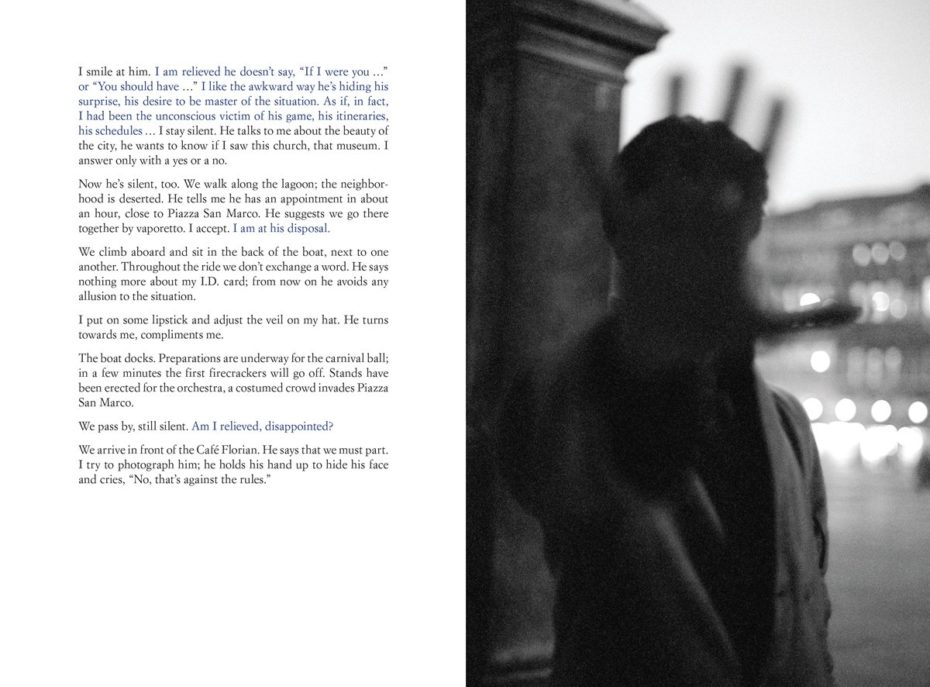

For Calle, the, well, calli, are a source of endless teasing and vexation. Often she loses Henri B., and it’s a long, cold wait to come across him again. But Calle isn’t deterred, for she has got it into her head that this isn’t merely about coincidence anymore, this about obsession. In her diary, she notes down that she has started to feel a connection between the two of them, a strange form of attraction.

Calle wasn’t the first person to follow strangers for art. The artist Vito Acconci had done it ten years earlier in New York, and called it, suitably, Following Piece. His constraints were that for the duration of one month, he would pick a random passerby and follow them until they entered a private space. Sometimes the act of following was but brief, sometimes it lasted for hours. Despite the obvious similarities between the two works, Calle has remained unperturbed by it, stating in an interview with the White Review, “The purpose of our projects was different, the motives too. Following people is something detectives do on a daily basis. Jealous lovers do it too. Following is an act that belongs to the entire world.” And anyway, as René Char once said, “Each act is virgin, even the repeated ones.”

After just under two weeks in Venice, the game is up. Henri B. recognises her “by her eyes” in the hospital of S.S. Giovanni e Paolo, a rambling structure that occupies the cloister of the church of San Zanipolo, where the way to the wards passes through a fifteenth century trompe-l’oeil creation, and where the medical library lives in the old chapter room of the Great School of Saint Mark. In 1980, the work is published as a book, with an afterword by her old professor, the French philosopher, Jean Baudrillard (it would be later republished in 2015 by Siglio). She calls it Suite Venetienne, from the Old French ‘sieute’ – an act of following, attendance, constituting a sequence, a series of movements; a hunt.

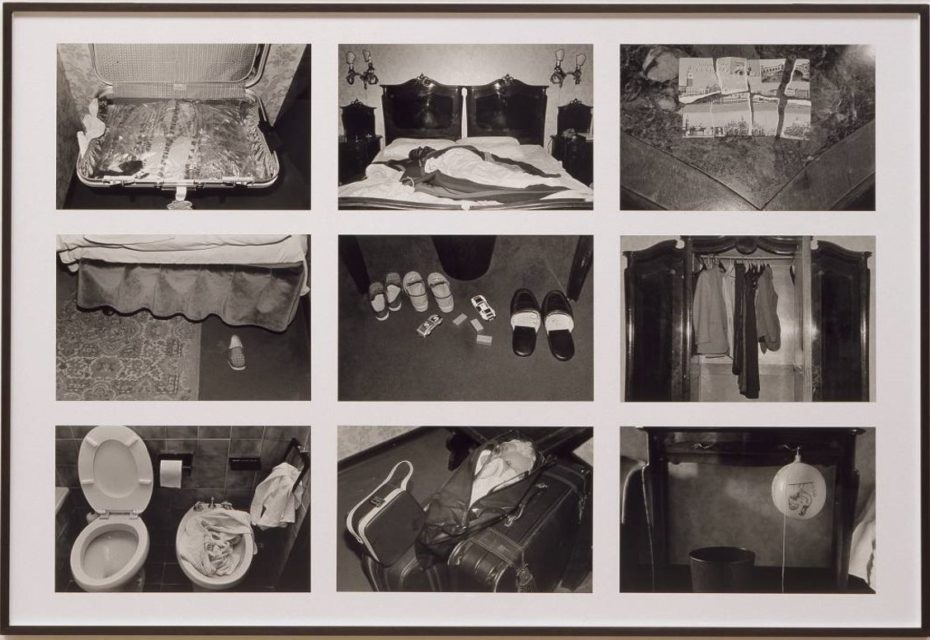

But the game continued, in Calle’s own way. Struck by how she would often imagine sleeping in Henri B.’s bed, she later got a job as a maid in the same hotel he stayed in, documenting the belongings of the guests whose rooms she cleaned in a work that would become The Hotel (1981). Also in 1981, in a work called La Filature – The Shadow – as a kind of nod to her previous role of detective, she requested that her mother hire a personal investigator to tail her, unaware that he was, in fact, the one being tailed. In yet another twist of the tale – for Calle’s work seems strangely alive, always in a series of movements, always, in other words, part of a suite – the writer Nicole Miller, in a piece for HyperAllergic, followed Calle in 2016, after a panel discussion at the Rubin Museum of Art in New York where she was the guest.

There was some risky business in 1983, when for The Address Book, Calle photocopied the contents of an address book she had found in the street before posting it back to its owner. Using the information she had photocopied, she sought to create an image of a person she had never met by contacting the people he knew: “I found an address book on the Rue des Martyrs . . . I will contact the people whose names are noted down. I will tell them, “I found an address book on the street by chance. Your number was in it. I’d like to meet you.” Pierre D., as she called him, was not happy when he saw her work being serialised in the Parisian newspaper, Libération and realised it was his address book. In retaliation he sent intimate photographs of Calle to the press, an act he deemed as invasive as hers. As a result, Calle agreed not to publish The Address Book in its entirety until after his death in 2012.

Throughout the eighties and nineties Calle produced various works – there was The Blind (1986), in which she interviewed those without sight and asked them to define beauty; in 1996 there was the film No Sex Last Night, created in collaboration with the photographer Gregory Shephard, in which she documented their road trip across the US; 1998 saw The Gotham Handbook, in which she augmented a telephone booth in Manhattan with a notepad, a bottle of water, a pack of cigarettes, flowers, and cash, cleaning the booth and replacing the items every day until the telephone company removed them.

But it was on the night of October 5th 2002 that Calle went to bed at the top of the Eiffel Tower. It isn’t exactly every day that one gets to sleep at the top of the iconic structure, so Calle invited people to read to her and keep her awake for as long as possible. She called it, suitably, Room with a View.

In a caption that forms part of an image of her, in a long white dress on the viewing platform, a pillow behind her head like a halo, she writes, “I asked for the moon and I got it: I SLEPT AT THE TOP OF THE EIFFEL TOWER. Since then, I keep an eye out for it, and if I glimpse it along some street, I say hello. Give it a fond look. Up there, 1,014 feet above ground, it’s a bit like home.”