You can’t beat a bit of Fanny, especially in the kitchen. Overshadowed by modern day macho MasterChefs, Fanny Cradock paved the way as the first ever celebrity chef and remains one in a million, like a dish you can perfect just once and never recreate. Spicing up British TV from the mid-1950s-70s, folks tuned in with dark fascination at her questionable culinary creations, sharp tongue, and flamboyant style. So much more than some light-hearted teatime inspiration, Ms Cradock was as complex and curious as her recipes. A true post-war pop cultural icon who wore her private life on her rolled up sleeve. Eccentricity was her secret ingredient; a rare item usually found at the back of the cupboard and best served refrigerated. Tuck in!

Phyllis Nan Sortain Pechey, or Fanny Cradock to friends and foe, had a bumpy start in life before she reached the bright lights of the BBC. Born in London in 1909 to gambling parents with a penchant for nice things, the family moved from one seaside town to the next to keep debt collectors at bay. Cooking wasn’t on the cards for Cradock in her early years. After getting expelled from boarding school for holding a séance in the school library, she had a brief stint as a dress maker and sold cleaning products door-to-door. In between precarious jobs, she got married four times, twice bigamously, became a pregnant widow aged 18, and made up new names and ages for each marriage certificate.

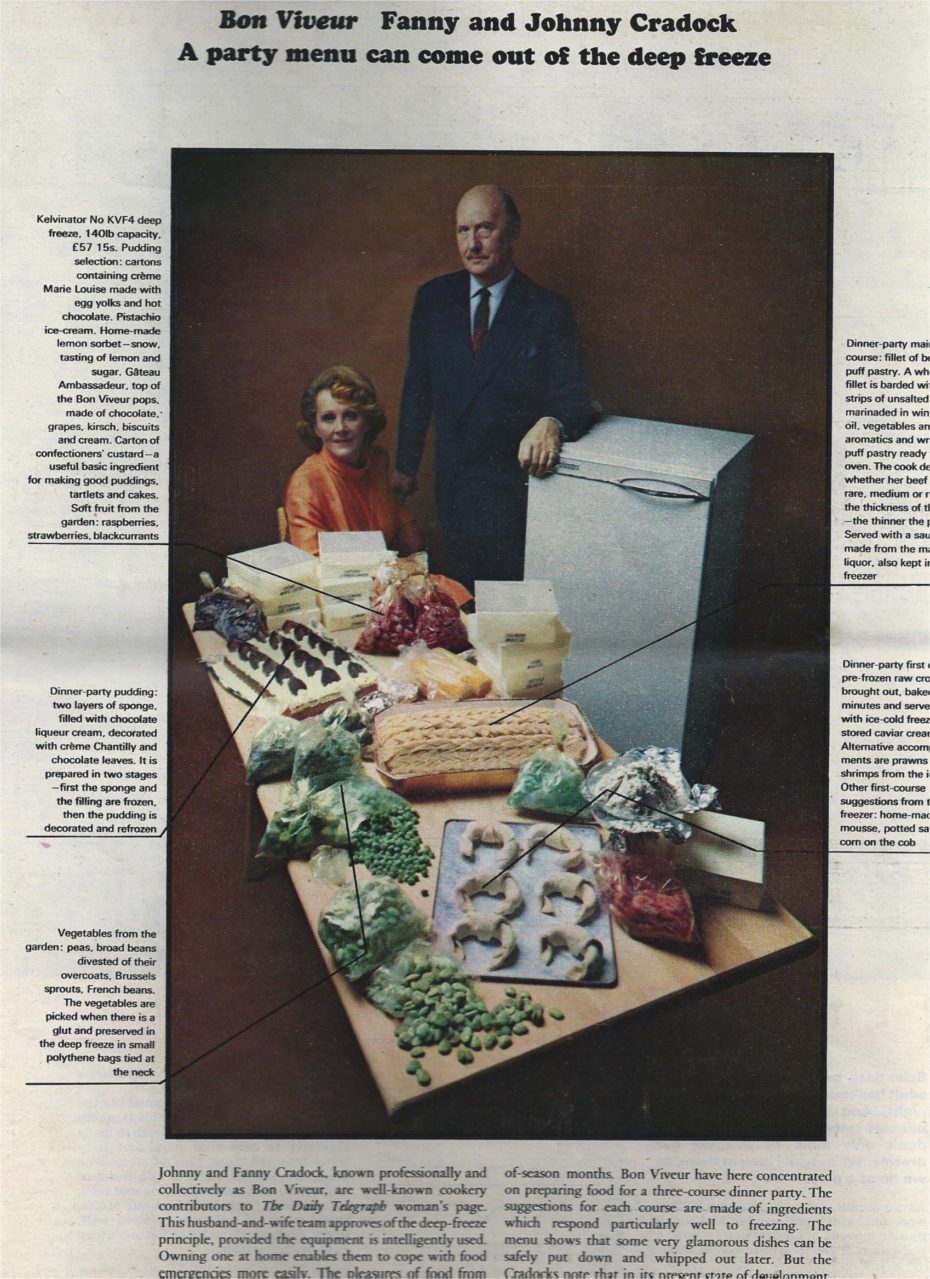

Fanny’s fortunes began to change when she started working in restaurants and formed some strong opinions on what was good and bad in British and French cooking. In 1950, alongside her husband and last love Johnnie, Fanny penned a popular newspaper column under the pseudonym ‘Bon Viveur’. From this, the pair used their love language of food to create an unlikely live stage show, turning theatres into pop-up restaurants for the night. Together they would comically dish up meals to patrons while playing up to the role of a bickering married couple.

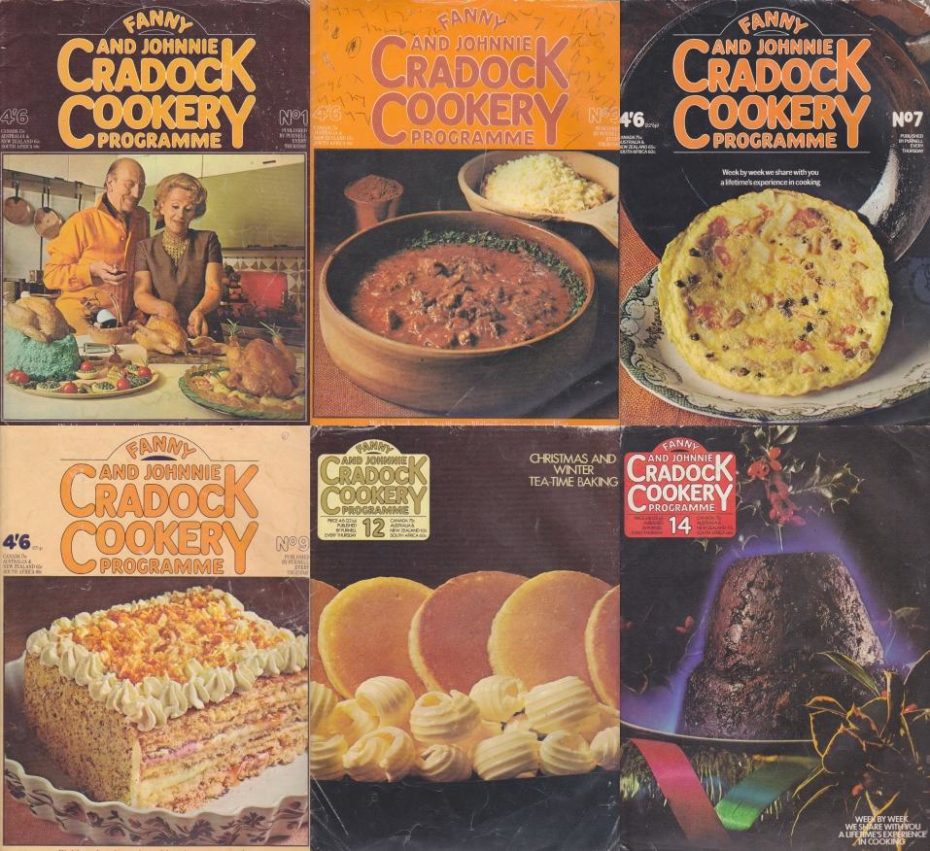

Forever a spinner of many plates and holder of a criminal number of identities, before her television debut in 1955, Fanny published 6 cookery books, 11 novels, 10 children’s books and 15 travel guides. Aliases included Francis Dale, Susan Leigh, Bon Viveur and Phyllis Cradock.

After filtering through her multiple fake names, the BBC tracked Fanny down to record a pilot cookery show, which ran for 20 years and propelled her into the living rooms and kitchens of British homes up and down the country.

Clad in extravagant chiffon ballgowns without an apron in sight, colourfully chaotic Fanny offered economical recipes for cash-strapped post-war families. She brought fun back to food after years of strict rationing and pioneered a new genre of educational TV entertainment. Accompanied by sometimes sous-chef Johnnie, who continued to play the role of bumbling hen-pecked husband, Fanny’s off the cuff creations encouraged housewives to get a little more exotic with their meal planning.

Dressed like a culinary pantomime Dame, Fanny ruled with an iron skillet and a sweet tooth. With unorthodox techniques and a dictatorial delivery, you could say she was an acquired taste. She treated her audience, the Great British public, like gastronomic philistines, and was scathing in her critique of her home country’s food. In fact, she said ‘the English never had a cuisine. There is nothing English. Yorkshire pudding came from Burgundy’. All of her recipes had French names. The irony is, Fanny’s food and her is-she-joking-or-not sarcasm was so classically British, it later became representative of the nation’s culinary identity in years to come.

Take the classic hors d’oeuvre, the prawn cocktail, for example. Perhaps the kitschiest starter there ever was. Invented by Brit-bashing Fanny in the 1960s, it rose to the height of fashion in the 70s. Although these days considered passé or served with a wry smile, it remains a retro camp classic, symbolising an old school English dinner party.

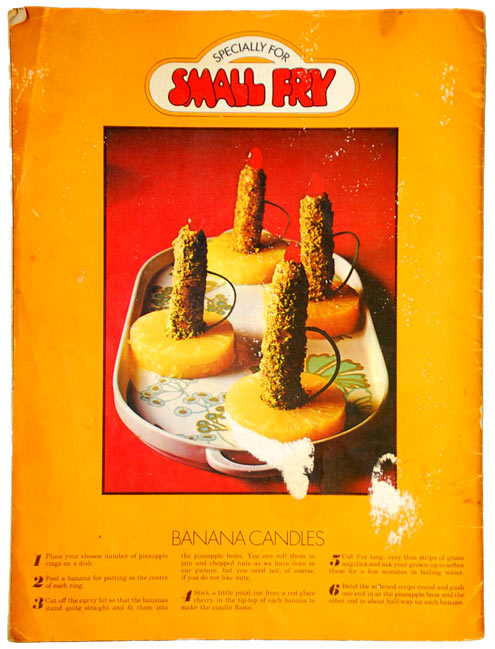

Millions flicked Fanny on their TV to broaden more than just their culinary repertoire and waistbands. After all, some of her offerings were questionable to say the least. First off, everything was spiked with artificial food colouring or laced with brandy, or both. Perhaps getting drunk was necessary if you’re going to give her green gruyère ice cream a go. Anyone for egg lemonade, or mincemeat omelette dusted in icing sugar? For the more rebellious cooks amongst us, Fanny has a step-by-step guide for a mean swan pie, one slight catch though; eating it breaks UK law.

Fanny Cradock became an unlikely style icon, with a fashion game as strong as her opinions. In her prime in the 1970s, looking like the lovechild of Julia Child and Dame Edna Everage confused her growing audience, sadly subjecting her to ridicule. However, her unique palette of prim and proper flamboyancy, shady remarks and overuse of glacé cherries has since established her as a niche gay icon and a source of inspiration for the drag community who have a natural affinity with those pencilled on eyebrows and overlined lips. Back on her home turf of Leytonstone in East London, a group of 25 dragged up Fanny fanatics hark back to the Cradocks’ theatrical variety shows and host a queer celebration for the queen of campy cooking. Audience members are invited to ‘come as Fanny, or come as Johnnie’.

Fanny’s televised culinary pursuits were bound up with her tumultuous private life, combining the worlds of celebrity and cheffing for the first time ever, making for compelling watching. People tuned in not just for the food, or even the fashion, but for the fact that deep down we are all suckers for the emotional rollercoaster that is reality TV. Fanny was a complex creature with a commanding personality, reviled and relished in equal measure. She tried to uphold a smokescreen of a perfect housewife and gastronomical whizz, all while baring her flaws and her marriage for the nation to see.

Fanny’s TV career spanned two decades and lasted 24 seasons, making her a figurehead of post-war pop culture. Unlike other cooks of this era who were mostly male and traditionally confined to professional kitchens, Fanny regularly appeared on game shows and brought glamour to late night chat shows, doing all the things you’d expect of a celebrity. Alongside filming she continued to be a mistress of reinvention, pioneering the subtle art of product placement and adding to her varied catalogue of written publications from romance novels to books on freezer food.

It all came crashing down in 1976 when Fanny appeared alongside a competition winner on a show called ‘The Big Time’ and gave us a sneak preview of “Kitchen Nightmares” thirty years before Gordon Ramsay came along. As the amateur cook shared her prizewinning menu with Fanny, a few too many grimaces, eye rolls and a couple of novelty gags thrown in for good measure, landed the celebrity chef in hot water and a victim of cancel culture:

National newspapers tore into her with unified wrath, describing the events as ‘Cruella de Vil meets Bambi’. Fanny soon issued an apology for her behaviour but the damage was done and the recipe ruined as the BBC terminated her contract 2 weeks after broadcast. In today’s world where red hot tempers help ratings and Gordon Ramsey is making literal idiot sandwiches out of people, it seems a little harsh on old Fanny.

After the career-ending broadcast, Fanny revisited a trend from childhood and escaped to the seaside once again. She lived out her final years by the English coast with Johnnie until her death in 1994. Like many game-changers in history, it’s often the overlooked, underestimated and in this case, ridiculed ones, that make the biggest splash.

Much more than the concocter of the prawn cocktail and trailblazer of retro nibbles, Fanny introduced unusual European dishes, such as pizza, to the English palette. Sure they weren’t all hits, but she helped families deal with the economic realities of the era, focusing on recipes that required cheap ingredients and brought top kitchen secrets to the front-of-house. Most of all though, without Fanny, a whole genre of TV and a bankable new breed of celebrity wouldn’t exist. Sadly, Fanny’s impact isn’t given its dues and her greatest asset, her eccentricity, meant she wasn’t taken as seriously as she should be. Even on her childhood home where she was born, a blue plaque marking the site’s significance spells her surname incorrectly.

During festive periods in the UK years after her demise, the popular episode ‘Fanny Cooks for Christmas’ gets pulled out of the archives for an annual nostalgic screening on the BBC. But remember, gaudy and garish recipes aren’t just for Christmas. Why not throw a 70s dinner party of your own? I’m thinking prawn cocktail, ornamental jellied meats and a black forest gâteaux to finish. If that sounds a bit too ambitious for you, next time you’re trying to cobble together a midweek meal from the random contents of your fridge, put on some pearls, take a generous glug of something strong, and keep calm and Fanny on. She was making it up as she went along most of the time too.