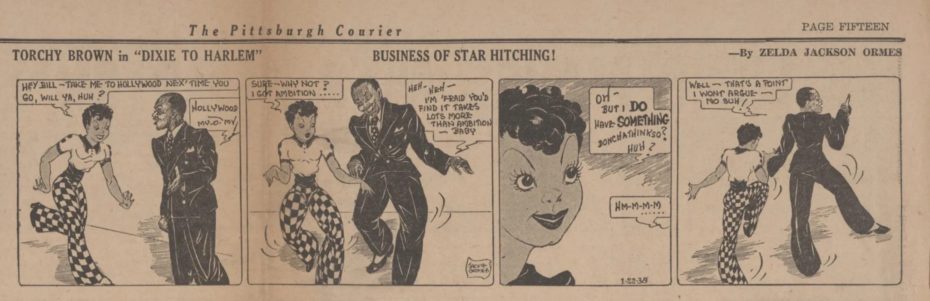

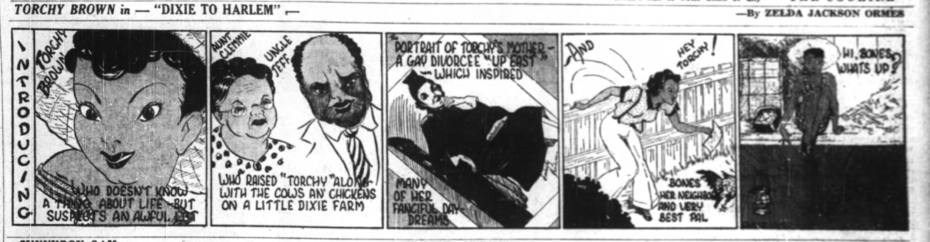

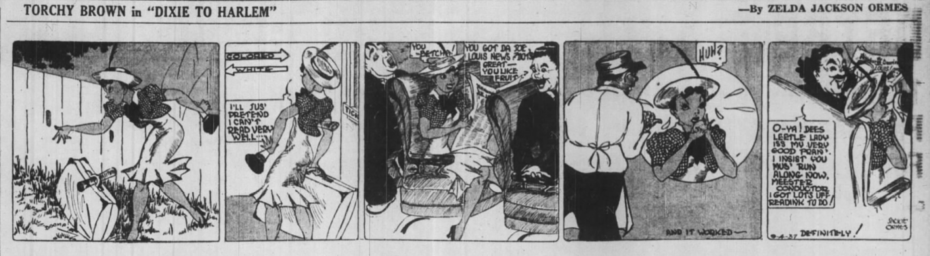

In the comic strip Torchy Brown from Dixie to Harlem, a spunky Black teenager leaves her Mississippi home for the bright lights of Harlem. She’s glamorous, ambitious, clever, and so self-assured that when she sees a sign pointing one way for COLORED and another way for WHITE, her response is, “I’ll just pretend I can’t read very well.” It was 1937, twenty years before anyone ever heard of Rosa Parks, and the author of the comic was a Black woman, Jackie Ormes.

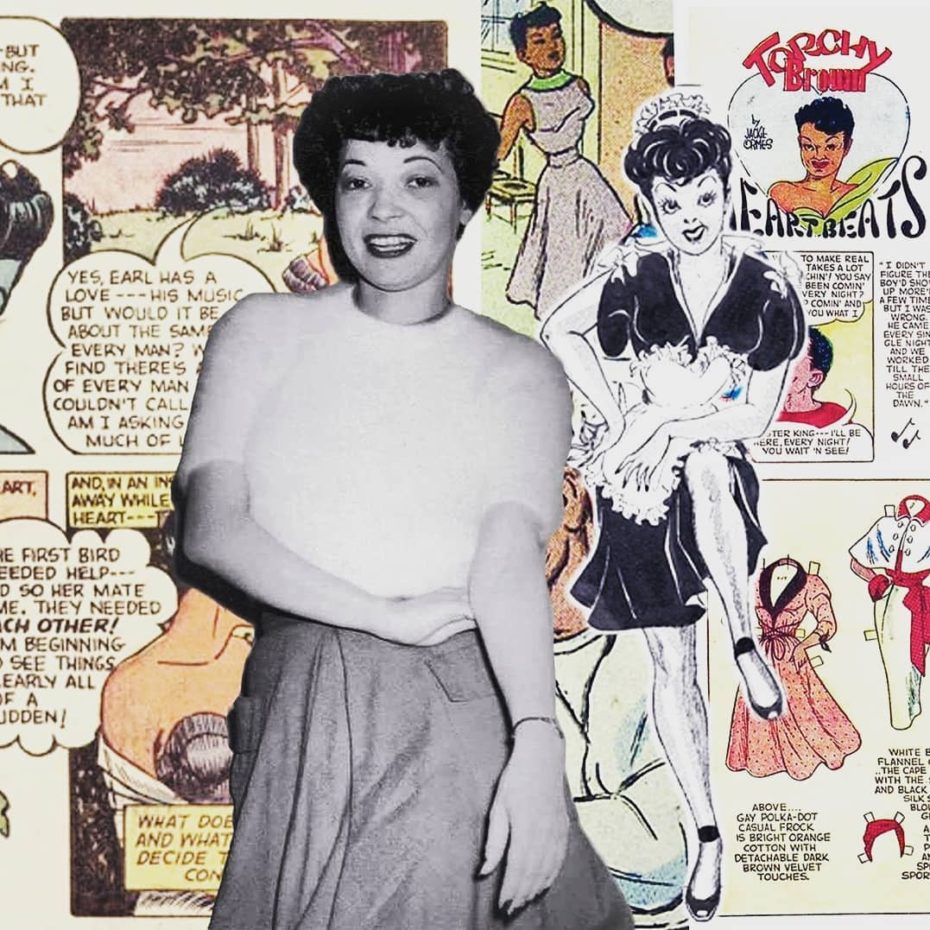

Born Zelda Jackson in Pittsburgh in 1911, Ormes modeled her plucky protagonists on herself and the people she knew. At the age of six, her father died in an automobile accident, leaving a household of women to fend for themselves. Her mother got a job as a live-in maid, leaving Ormes and her older sister with their aunt. While still in high school, Ormes elbowed her way to a job at the Pittsburgh Courier. After pestering the editor with letters, she became a proofreader for the paper before receiving her first assignment, a Joe Lewis boxing match. Being underage, she had to be chaperoned by the editor of the paper. “It wasn’t a ring at all,” she wrote, “It was a square— square as all git out. The sportswriters were sitting around the edges. They were getting splattered. With sweat. It was nasty, and I was enjoying it.”

For five years, she worked at the Courier and “enjoyed a great career running around town, looking into everything the law would allow and writing about it.” But what she really wanted to do was draw.

She married Earl Ormes in 1936 and they moved to Bronzeville, Chicago’s answer to Harlem, where they soon became a power couple in the Black community. Earl Ormes was a banker, who later managed several luxury hotels, including the famed DuSable Hotel, where he and Jackie rubbed elbows with Lena Horne, Eartha Kitt, Cab Calloway, and Sarah Vaughn.

In May of 1937, Torchy Brown from Dixie to Harlem was introduced in the Pittsburgh Courier. Modeled physically on Ormes and partially based on Ormes’ sister who sang torch songs, Torchy Brown is an ambitious Black teenager “who doesn’t know a thing about life but suspects an awful lot.” Because the Courier was a Black newspaper, Ormes had the freedom to draw Black characters that defied racial stereotypes. Torchy was a hit and the comic was soon syndicated in all the sister papers of the Courier, appearing in 14 cities across the country from 1937 to 1938.

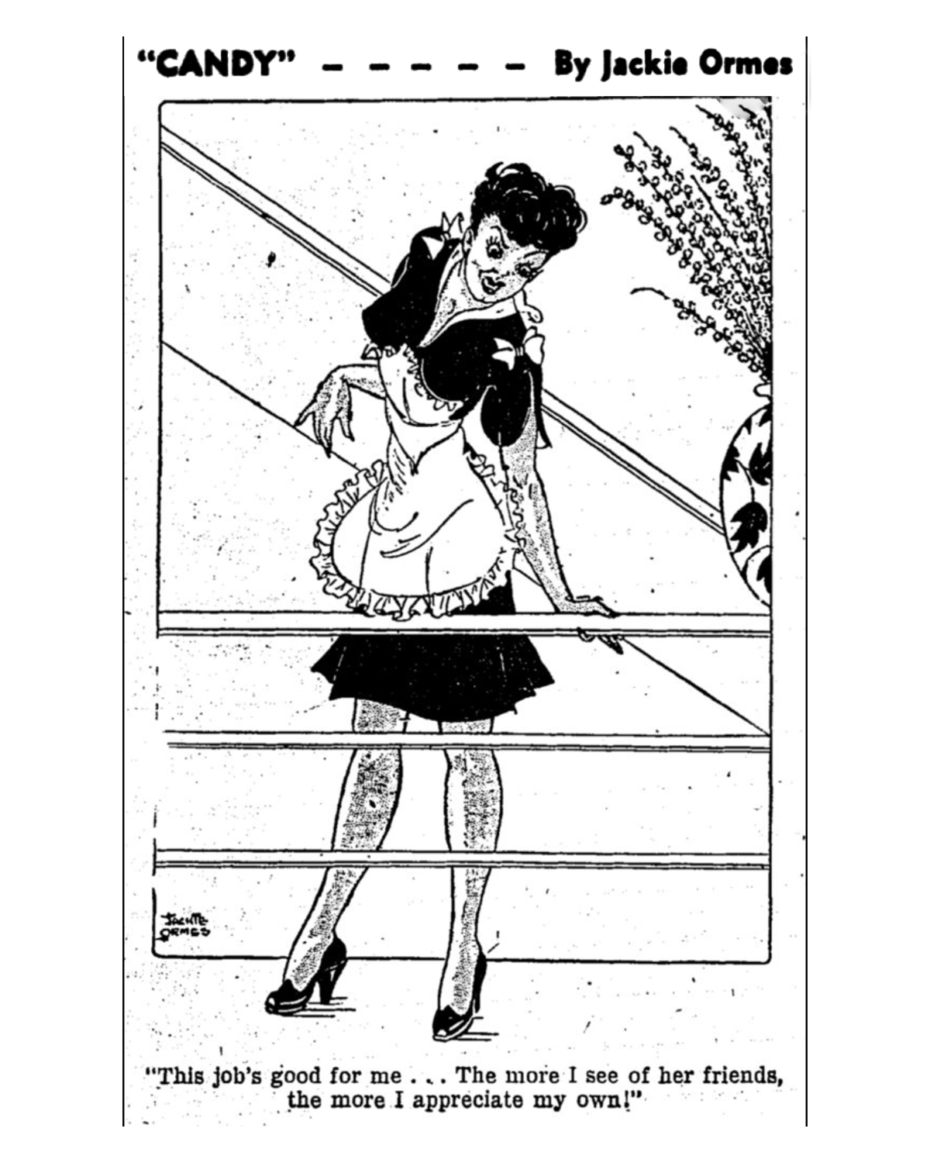

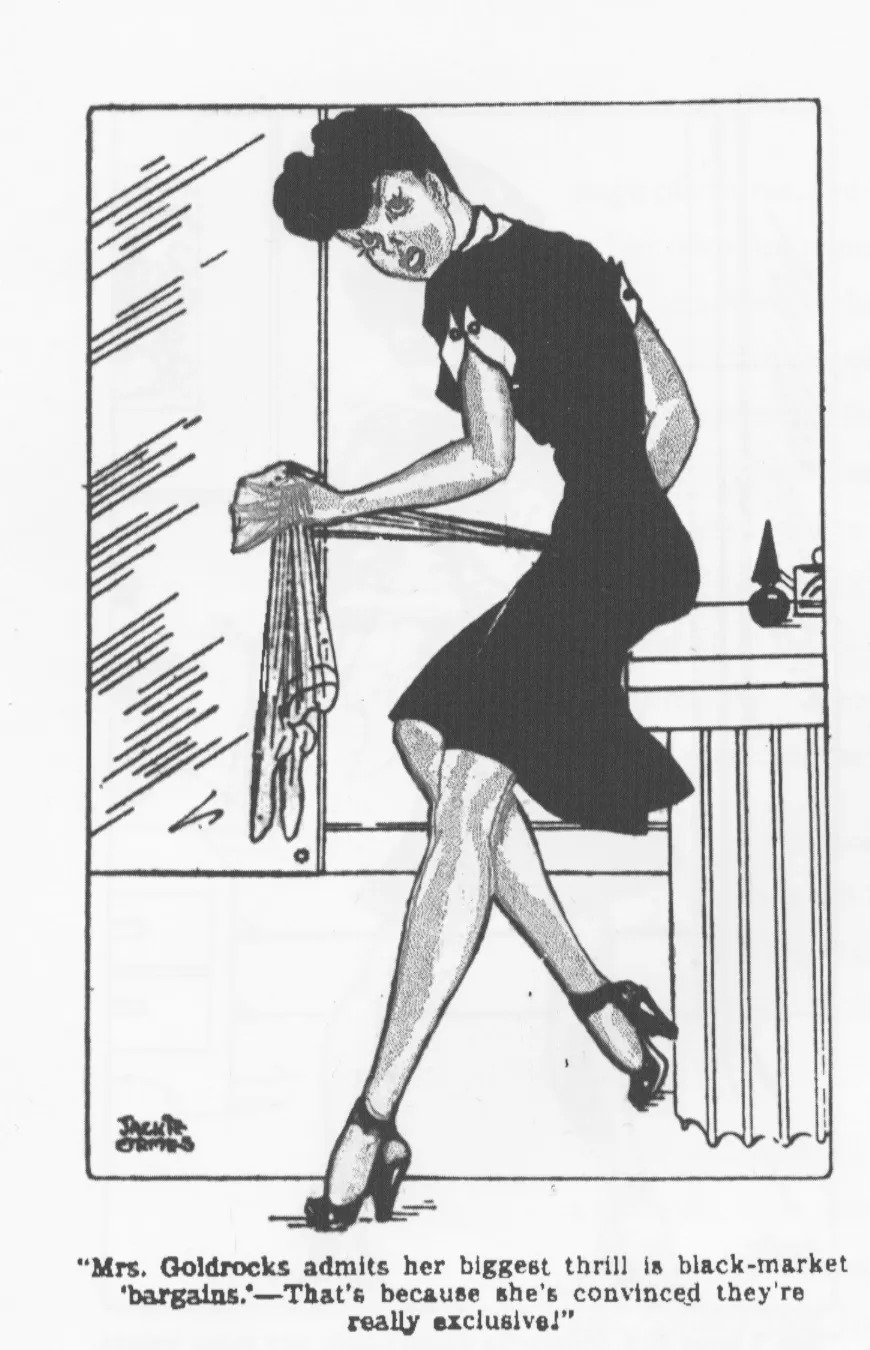

During World War II, Ormes freelanced as a reporter for the Chicago Defender, the most important Black newspaper of the time. She became an outspoken advocate for the Double V Campaign, which called for victory in the war overseas and victory against racism at home. For several months in the last year of the war, Ormes also provided Black servicemen with a pin-up they could place on their lockers without fear of reprisal. Her one-panel comic “Candy” reinvented the Black maid stereotype with a sexy, sassy, Black maid who continually demonstrated that she was prettier, smarter, more resourceful, and better dressed than her unseen white employer, Mrs. Goldrocks.

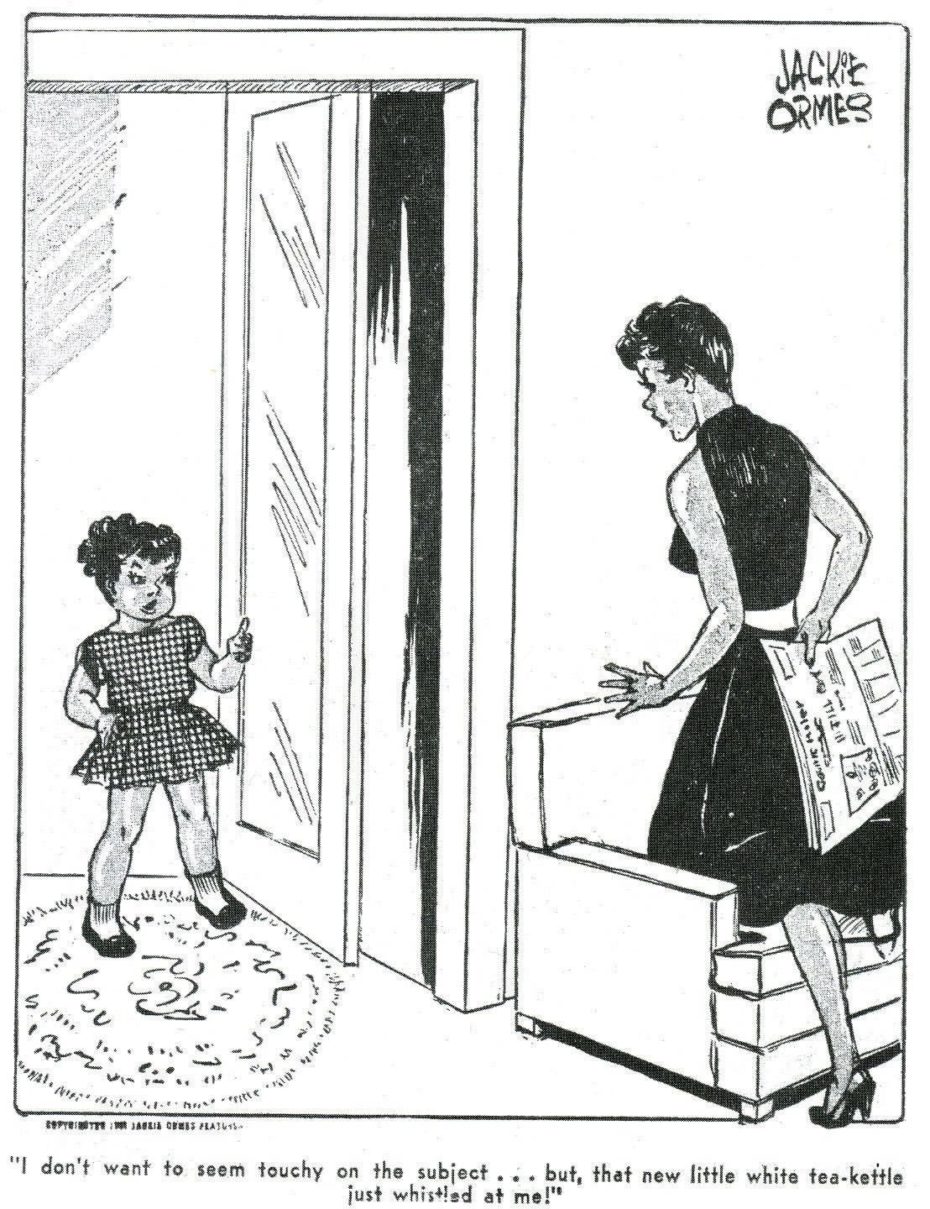

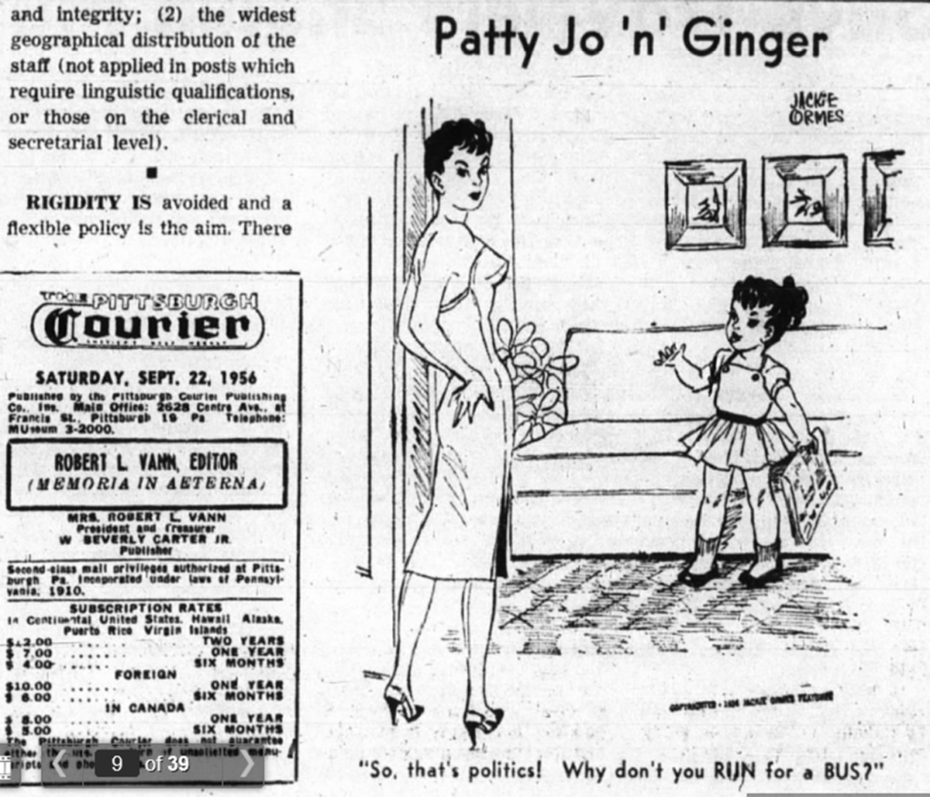

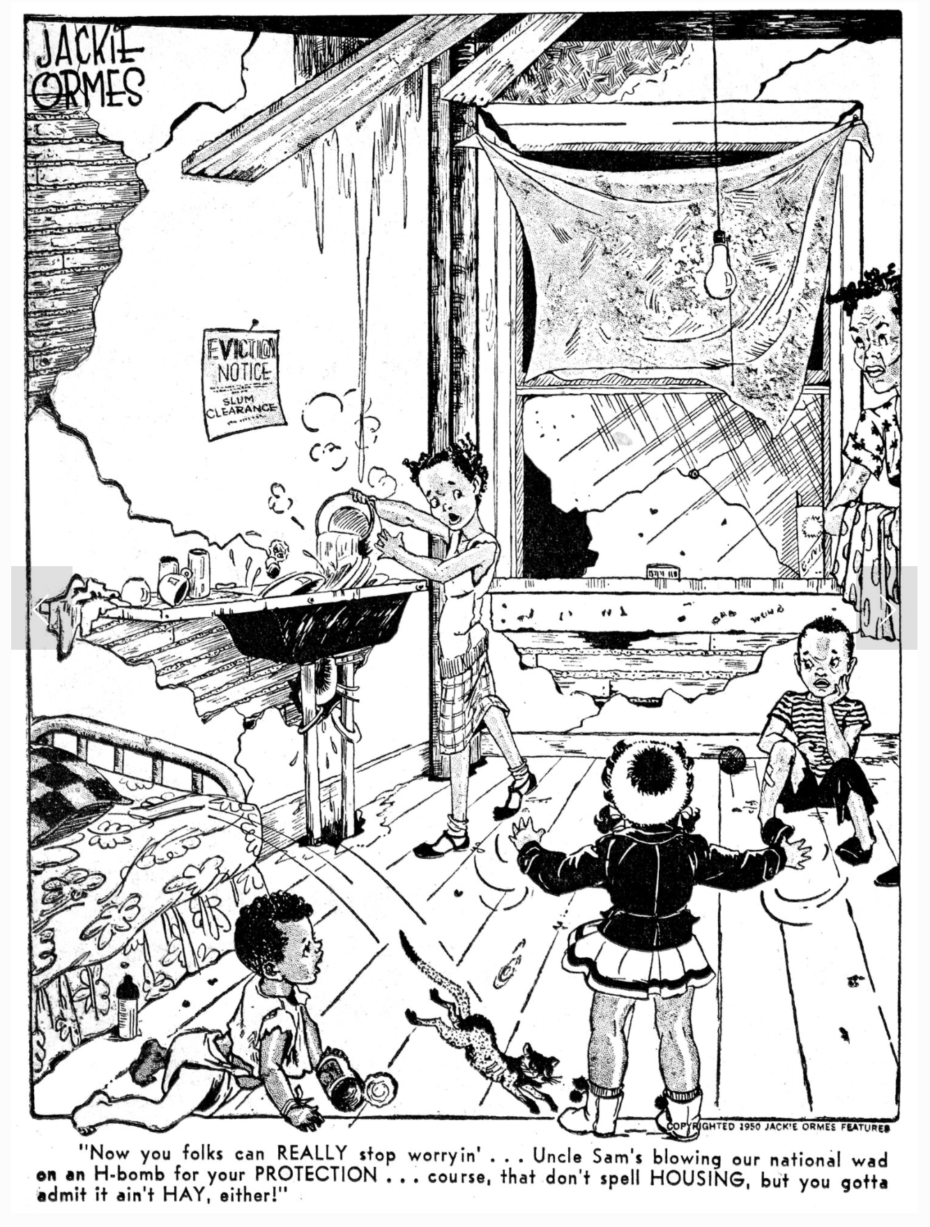

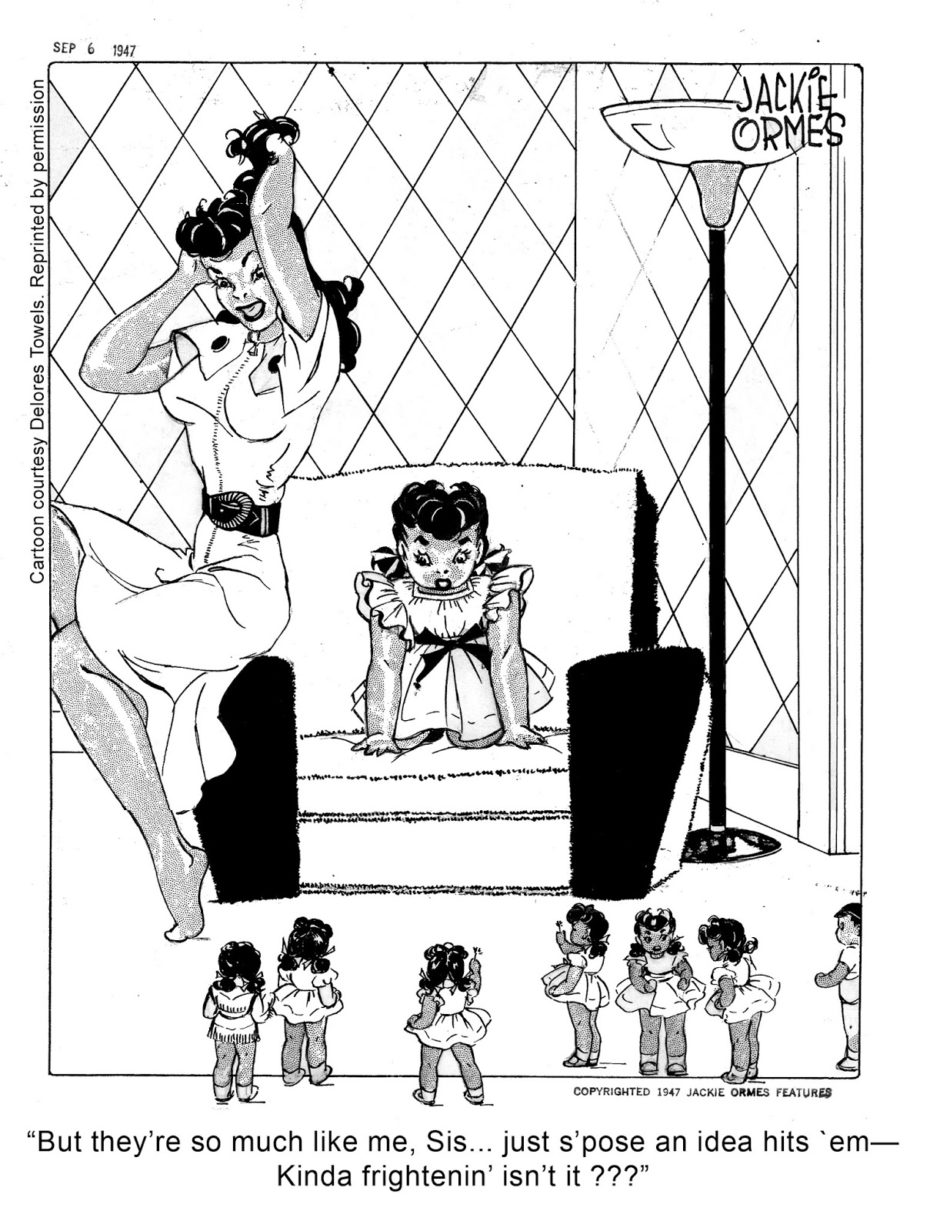

Ormes’ only daughter, Jacqueline, died of a brain aneurysm at the age of three. Not wanting to repeat the heartache, Ormes never had another child, telling her sister Delores, “I will never lose my empty arms.” Several years later in 1946, she started to draw her most popular comic, Patty Jo ‘n’ Ginger, featuring a precocious little Black girl about the same age as Jacqueline when she died. For the next eleven years, Patty Jo never grew up, remaining a feisty, opinionated four-year-old with biting commentary on everything from racism to sexism to McCarthyism, as her gorgeous older sister Ginger wordlessly preens or reacts with surprise.

Ormes was a collector of dolls and had always been dismayed by the Black dolls that were available. With few options beyond Black mammies or pickaninnies dressed in rags, Ormes observed little Black girls playing with white dolls as if they were training for careers caring for white children. She began designing a doll in the image of Patty Jo. After an extensive search for a manufacturer, a friend recommended the Terri Lee Company, founded by two women in their kitchen in Nebraska. Ormes traveled to Nebraska and began collaborating with the company to produce a 16″ plastic doll, proclaiming in an interview, “No more rag Susies or Sambos… Just KIDS!” The Patty Jo doll was on store shelves in time for Christmas 1947. A vast cry from the racism of other Black dolls on the market, Patty Jo had soft hair that could be styled and an elaborate wardrobe that included dresses, formal wear, skating outfits, nightgowns, matching shoes, and spring and winter coat sets. Produced from 1947 to 1949, original Patty Jo dolls are now collector’s items fetching thousands of dollars.

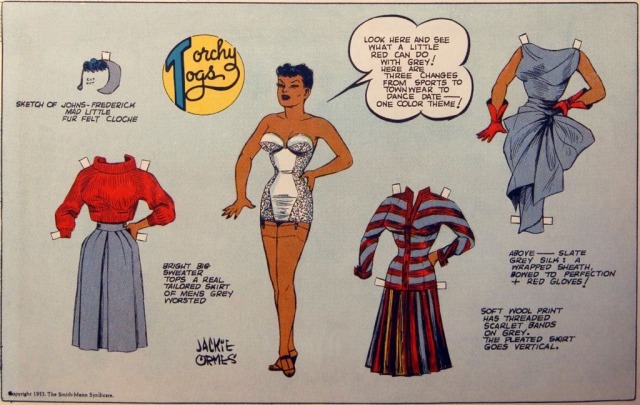

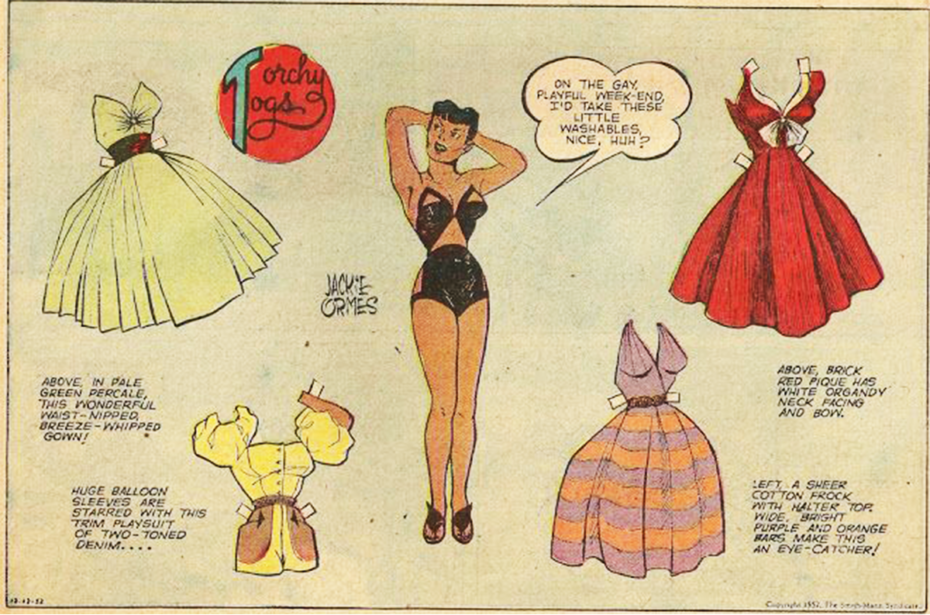

In 1950, when the Courier began publishing an eight-page color comic insert, Ormes returned to her Torchy Brown character. This time, a savvy grown-up Torchy falls in and out of love as she takes on controversial social issues in Torchy Brown Heartbeats. Redefining notions of womanhood and Blackness in the 1950s, Torchy Brown was beautiful, fearless, smart, and self-reliant, even as she yearned for love and romance. Unlike Brenda Starr whose adventures were mostly romantic, Torchy battled racism, an attempted rape, and even tackled environmental pollution, years before other comic strips approached these topics. Each week, there was also a Torchy Brown paper doll with gorgeous dresses and gowns, giving Black girls a style icon to dream about.

Rheumatoid arthiritis ended Ormes’ career as an artist in 1956 but not her fight for racial justice. As the civil rights movement gathered steam, she was active in the NAACP and presided over the women’s auxiliary of the Urban League. She was also a founding board member of the DuSable Museum of African-American History, the first museum dedicated to Black culture. Her activism led the FBI to amass a 287-page dossier on her.

Sixty years later, it’s still rare to see comics by women, let alone Black women. After Ormes retired, there were no other nationally syndicated comics by Black women for three decades. From 1989 to 2005, there was exactly one comic strip drawn by a Black woman, Where I’m Coming From by Barbara Brandon-Croft, who cites Ormes as an inspiration. A true trailblazer, Ormes was way ahead of the curve. “I have never liked dreamy little women who can’t hold their own,” she stated in an interview at the end of her life. Not only did Ormes transform stereotypes of the Black maid and the pickaninny into smart, assertive, attractive heroines, but she also created positive images of strong, sexy Black women, paving the way for Black is Beautiful and #BlackGirlMagic.

About the Contributor