Picture a night out in 1940s San Francisco. You’re in a glamorous nightclub with a floorshow. A sequined dancer does a pas de bourrée on her toes while her tuxedoed partner wows the crowd with multiple drop splits. Then a singer with a warm bluesy voice belts Some of These Days. Finally, a nude dancer strolls through the room, languorously waving enormous feather fans. Now what are the chances that any of the dancers you’re picturing are Asian-American?

For two decades, San Francisco’s Chinatown nightclubs proved that Chinese-Americans weren’t just cooks and launderers from a mystical land in a bygone era. They were snappy dressers who could really cut a rug, and not an Oriental rug either. In its heyday, there were six nightclubs with all-Asian floorshows in San Francisco, catering to a mostly white clientele with names to capitalize on their exoticism: The Dragon’s Lair, The Lion’s Den, Kubla Khan, The Chinese Sky Room, Club Shanghai. The most famous of all was Forbidden City.

The impresario of the Forbidden City was Charlie Low, who came to San Francisco from Nevada in 1922. It was the Roaring Twenties and Low persuaded a brokerage firm to open an office in Chinatown with him in charge. Then in 1927, when landlords refused to rent to his family because they were Chinese, he helped his mother build the first modern apartment building in Chinatown. Low loved the nightlife and after Prohibition ended, he turned to the bar business. In 1936, he opened Chinese Village, the first cocktail bar in Chinatown.

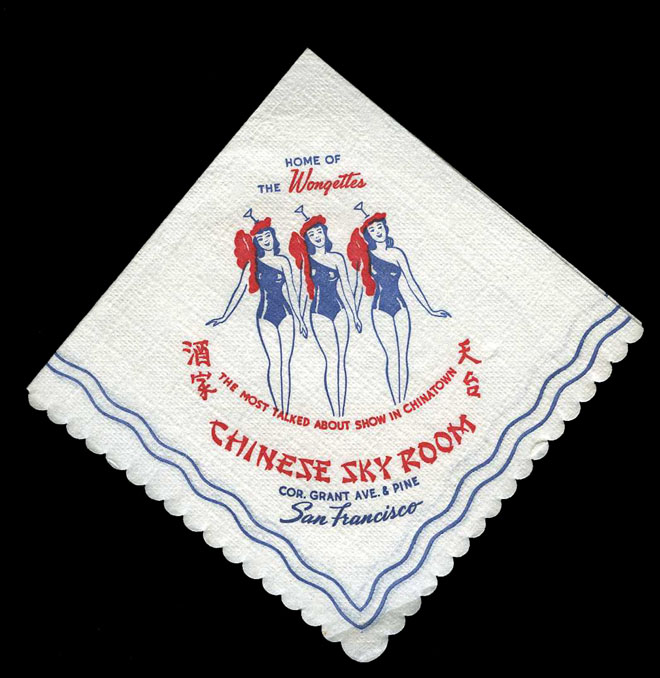

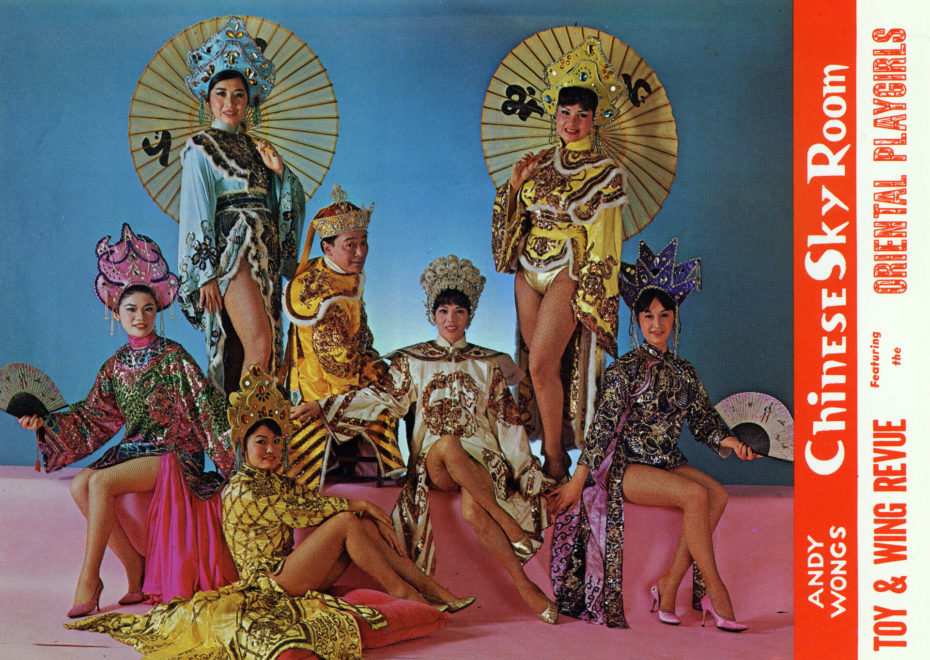

The next year, just down Grant Street, Andy Wong opened the first Chinese-American nightclub, the Chinese Sky Room. A trumpet player, Wong had gotten his chops playing funeral bands in San Francisco before joining a jazz sextet, the Chinatown Knights. They played benefits and community dances, but Wong wanted what he saw in the movies, a real nightclub where his band could play while glamorous couples glided about on the dance floor.

Low’s cocktail joint did well enough, but he saw what Wong was doing and got major FOMO. He thought he could do better, especially since his gorgeous wife, Li Tei Ming, was a torch singer. After finding a location a block away from Chinatown and filling it with Chinese tchotchkes, he opened Forbidden City in 1938. “I thought I would have a lot of trouble in recruiting a good Chinese floorshow,” Low remembered, “but I was quite lucky.”

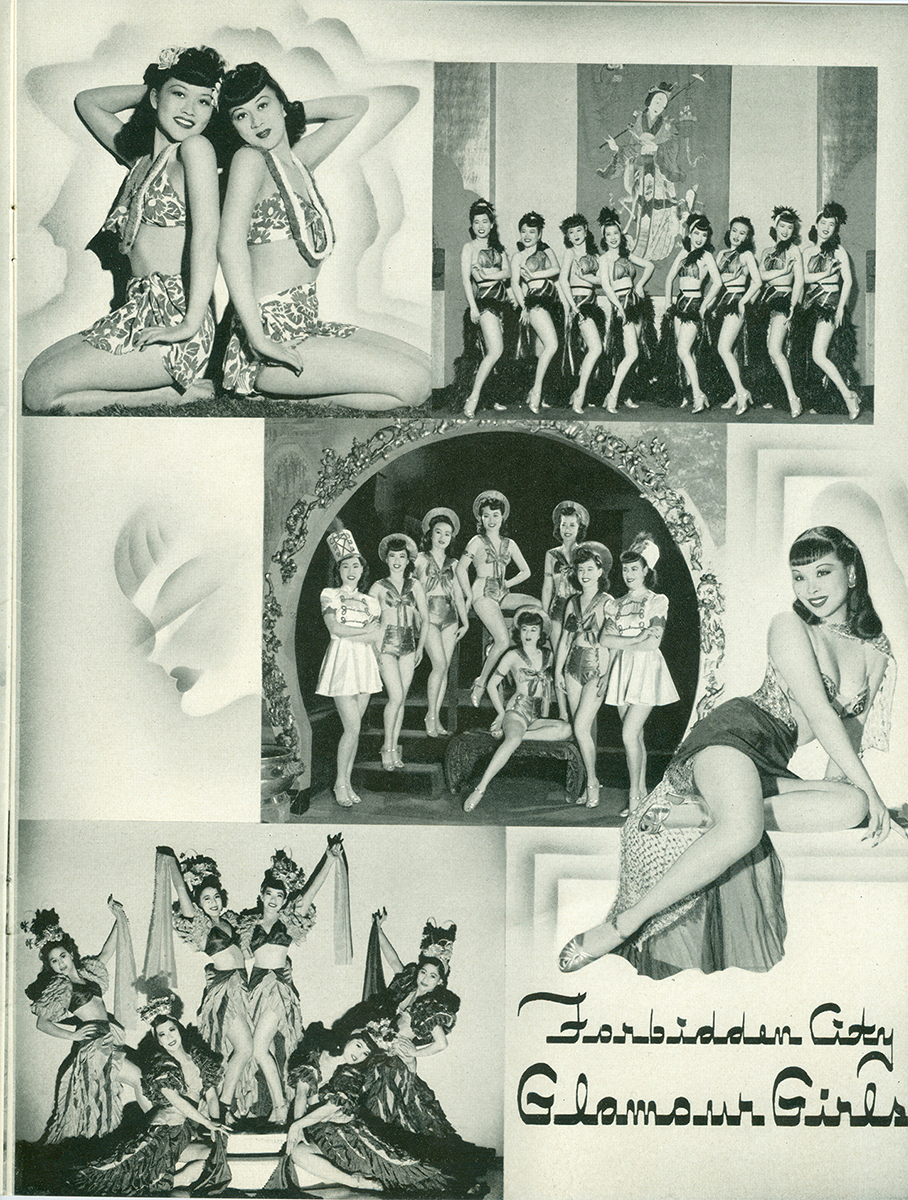

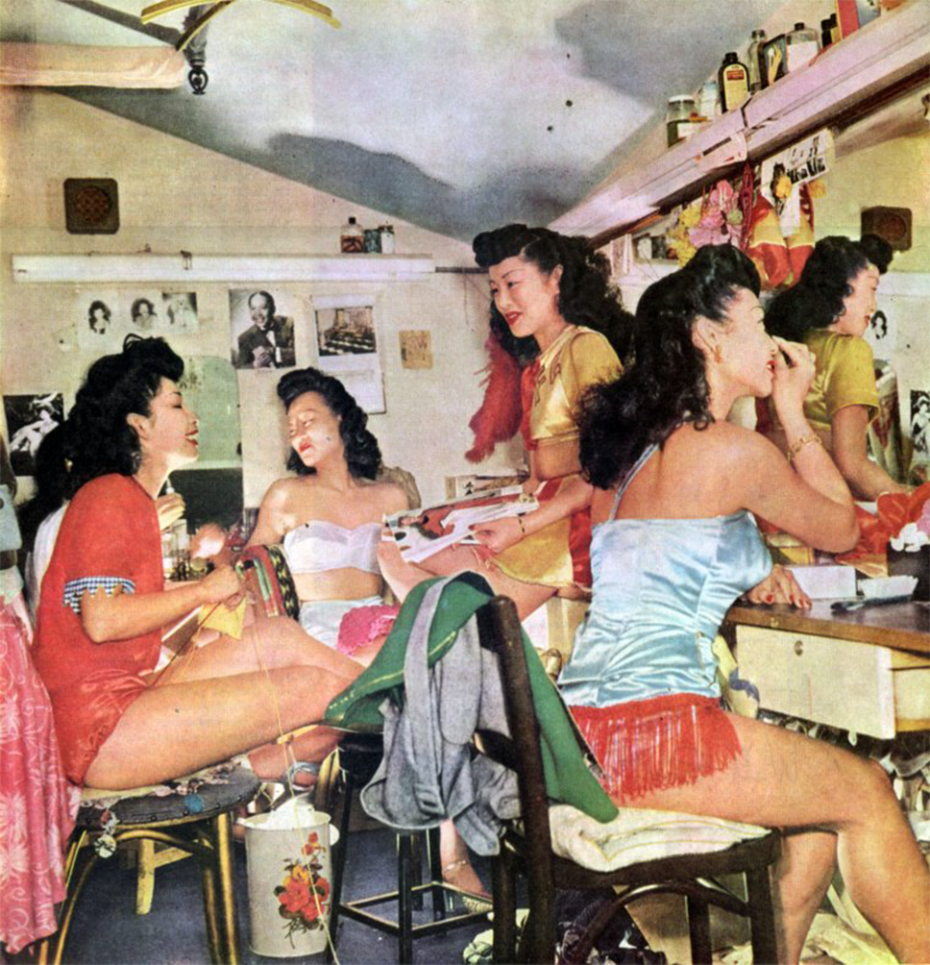

Low found his floorshow in a plethora of young Asian-Americans who had come to the city searching for work. Born in America, they had grown up with Hollywood musicals and jazz on the radio. Their parents, however, were Asian immigrants who had somehow come to America despite the Chinese Exclusion Act. Being nose-to-the-grindstone immigrants, they were not very supportive of the arts. Consequently, most of the Forbidden City performers had little training in music or dance. By going into show business, they were defying the expectations of both their Asian-American families and the dominant white society. The women had another level of rebellion against patriarchal notions of modesty and propriety.

Opening night headliner Ellen Chinn was a teenage runaway from Monterey who had been dancing for a few years before she landed at Forbidden City. Most of the chorus girls – among them Dottie Sun, Mary Mammon, and Mai Tai Sing – worked as cocktail waitresses while they learned to dance from the Forbidden City choreographer, Walton Biggerstaff, whose studio became a conduit for Chinatown nightclub talent.

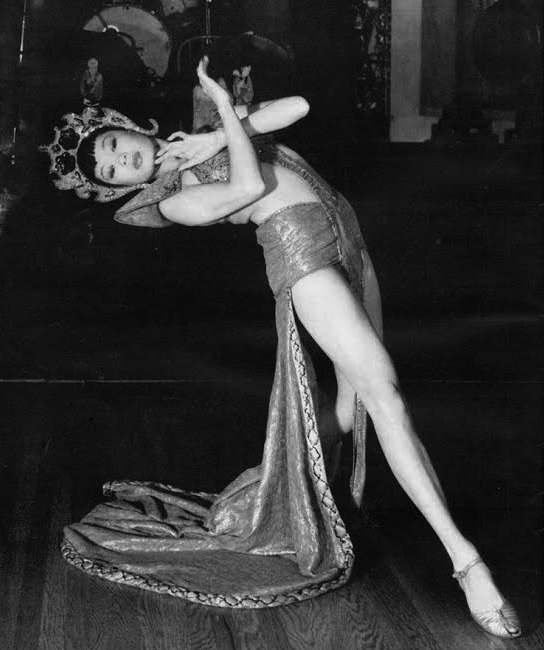

Another opening night headliner was Jadin Wong, who was one of the few to have formal dance training. Born to dance, Wong wasn’t about to let anyone stop her and she paid for her own lessons as a child. After running away from home to find fame and fortune in Hollywood, she was hungry and out of money. So she thought she’d tap dance on Hollywood Boulevard to make enough to eat. While she was hot-footing away, director Norman Foster happened to amble by. He invited her to lunch and then brought her home to meet his wife – the movie star Claudette Colbert. As a result of this fairytale meeting, Wong ended up in Mr. Moto Takes a Vacation, starring Peter Lorre in yellowface. A year later, she followed a dance teacher to San Francisco and ended up at Forbidden City.

Larry Ching joined the merchant marines in 1937 at the age of 17. He learned to sing by listening to records on the ship. When he mustered out of the marines, he got a job as a waiter at Charlie Low’s Chinese Village, where he honed his talents while serving chow mein and egg fu yung. With his good looks and suave style, Ching became known as the Chinese Frank Sinatra. “I always hated that handle,” he confessed, “I liked ‘Bing Crosby’ much better. But I really wished I could just be ‘Larry Ching.'” San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen declared, “’Frank Sinatra is really the Italian Larry Ching.”

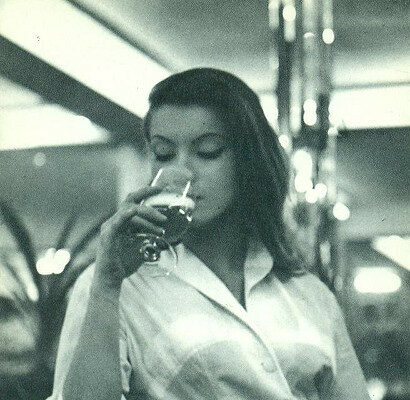

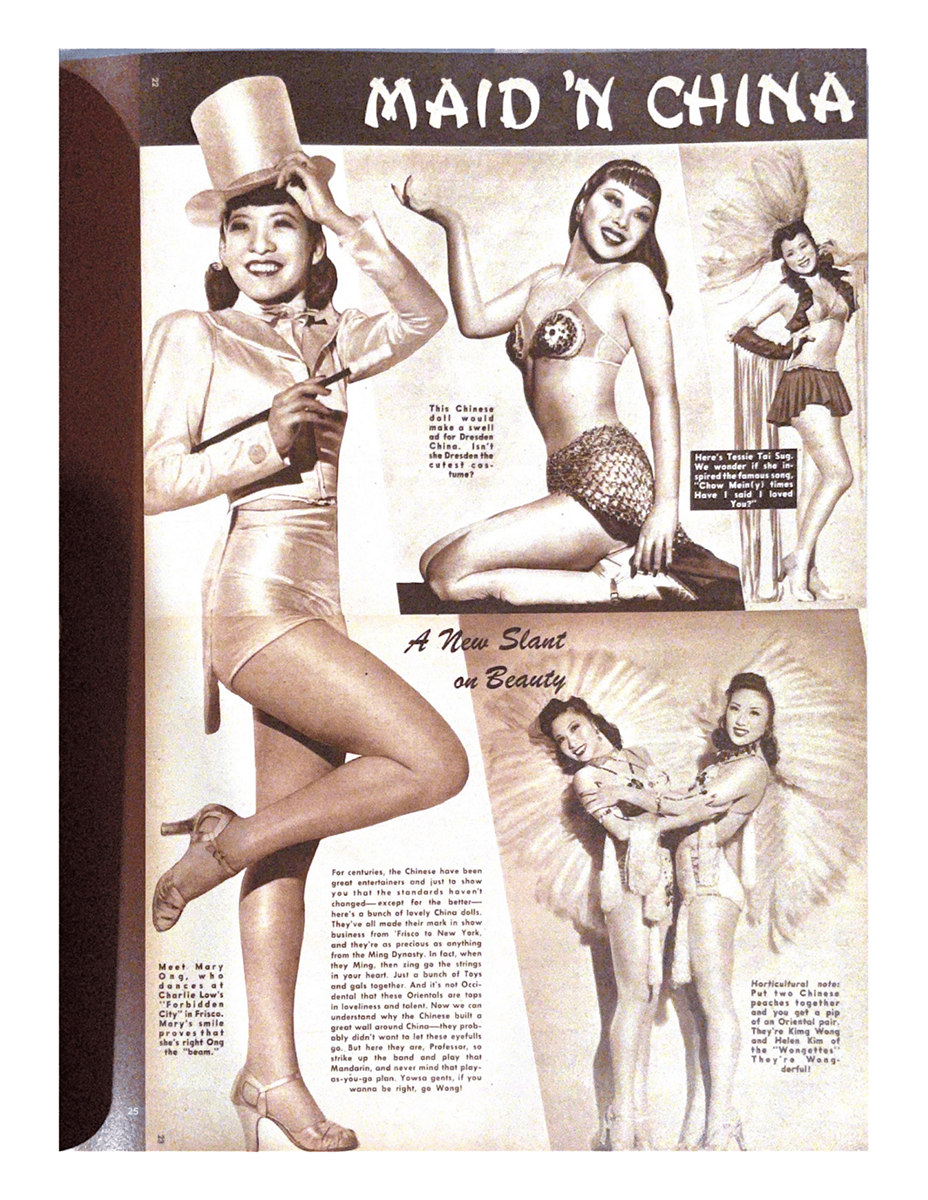

early 1940s. (DeepFocus Productions Inc.)

Patrons at Forbidden City had a choice of a Chinese or American dinner, along with drinks from a yard-long cocktail menu. There were three shows a night, each about 45 minutes long, consisting of singers, dancers, and variety acts. The floorshow typically began with a chorus line of girls in faux Asiatic robes, bowing and shuffling to gongs and flutes. The girls would then throw off their Orientalia to reveal spangly outfits showing lots of leg. From then on, everything in the show was American. The exotic, mysterious East was used to lure the largely white audience, but the Asian-American performers refused to perpetuate the stereotype. Singers sang the hits of the day. Dancers performed jazz, rumba, and the mambo. Burlesque performers were often decked out in exotica but they did the bump-and-grind just like their white and Black counterparts.

Business was slow at first and Charlie Low struggled to pay his employees. Then publicist Bill Steele suggested that Low hire a Chinese girl to mimic burlesque dancer Sally Rand, who was drawing huge crowds with her Nude Ranch at the 1939 World’s Fair in San Francisco. Low had no idea how to find an Asian-American girl who would be open to nudity, but then he met Chinese-American college student Noel Toy. She was employed at Candid Camera, another risqué World’s Fair attraction, making $35 per week posing nude as fairgoers took amateur photos of her.

Toy accepted Low’s offer of $50 a week to parade around his establishment with nothing but a giant balloon. Billed as the Chinese Sally Rand, advertisements suggestively sniggered, “Is it true what they say about Chinese girls?” Business started to hum with white patrons eager to confirm rumors about aberrant Asian genitalia. Noel Toy took this mix of racism and misogyny in stride, laughing in response to the lurid question, “Oh sure, it’s just like eating corn on the cob!”

Then there was the Life Magazine photo essay on December 9, 1940. The four-page spread called the Forbidden City “the No.1 all-Chinese night club in the U.S.” and featured a slinky photograph of Jadin Wong in an exotic costume, Li Tei Ming (Mrs. Charlie Low) warbling a song, and a chorus line of Asian-American girls in rumba outfits shaking their stuff. “Chinese girls have an extraordinary aptitude for Western dance forms,” proclaimed the magazine, “As singers, not many achieve success according to occidental standards. But slim of body, trim of leg, they dance to any tempo with a fragile charm distinctive to their race.”

Business tripled after the Life Magazine article and then quadrupled after the U.S. entered World War 2 in 1941. San Francisco was flooded with servicemen from all branches of the armed forces. Shipbuilding also brought hundreds of thousands of workers. Everyone flocked to exotic Chinatown nightclubs. They rubbed shoulders with celebrities like Errol Flynn, Ethel Waters, Ronald Reagan, Bing Crosby, Duke Ellington, and Frank Sinatra. Grey Line Tours sometimes dropped off five busloads of tourists for each show.

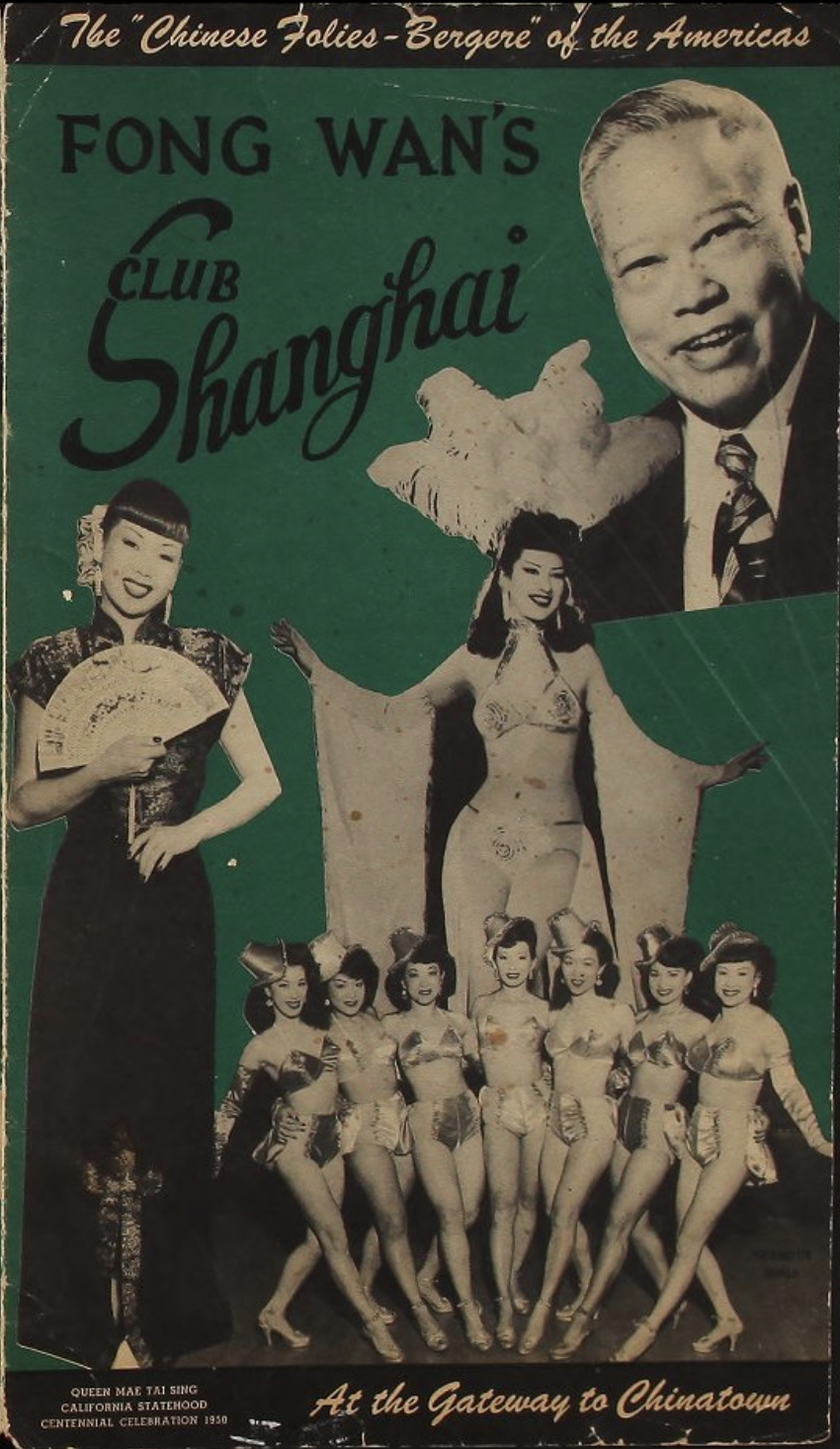

With business so good, other Chinese-themed nightclubs started to pop up. Asian-American entertainers suddenly found their slim work opportunities doubled with all these new nightclubs searching for Asian talent. It was soon called a chop suey circuit. In NYC, a white producer got in the game and opened the China Doll, which put on revues with racist names like Slant Eyed Scandals. There was also a club in Washington, DC. In San Francisco, there were eventually six clubs, all Asian-owned and primarily in Chinatown. Eddie Ponds opened the Dragon’s Lair, and then the Kubla Khan, a lavish-two story Chinese fantasia where he was known for playing maracas with the Latin house band. When wealthy Chinese herbalist Fong Wan took over the Club Shanghai in 1946, he and Charlie Low became legendary arch rivals. In 1949, Wan sued Low for $50,000 for poaching an acrobat from Club Shanghai. Wan even bought an empty building just to put up a giant neon sign redirecting patrons from Forbidden City to the his club around the corner.

Asian-American performers were so much in demand during World War 2, they toured for the U.S.O., the Stage Door Canteen, and the Red Cross. Jadin Wong purportedly parachuted into Germany and traveled secretly through the Black Forest to perform with Bob Hope at an undisclosed army base. If Asian-American performers faced danger in Europe, their experience of segregation in the South was unsettling. “I went to the Ladies Room,” remembered singer Frances Chun, “and I saw a sign that said Black and a sign that said White. So I stood there and I said now where should I go? Where do I belong?” Dancer Jackie Mei Ling remembered going to a diner in Louisville, “We waited and waited and waited and finally the hostess came by and said, ‘I have to ask you a terribly pertinent question: ‘Are you people black?’” Though they didn’t experience the outright hostility that Black performers encountered, they were not exactly accepted with open arms.

And there was the problem faced by Toy and Wing, one of the top Asian-American dance duos in America. Dorothy Toy performed athletic moves standing on her toes, while Paul Wing leapt in the air and landed in splits. They had danced in a Hollywood film, Happiness Ahead (1934), and they toured the RKO circuit of big-time theaters. In 1942, just as they were about to appear in a Marx Brother film, the Ed Sullivan Show outed Wing as Japanese. Sullivan got it wrong – it was really Toy who was Japanese. She had changed her real last name – Takahashi – because she thought it was too long. They fled to Chicago so she could avoid being sent to a detention camp and performed in lesser nightclubs to lay low. After Wing was drafted into the army in 1943, Toy continued performing with her sister during the War, but her parents were sent to a detention camp in Utah.

After the war’s end, the novelty of Chinese-American nightclubs started to fade, but there was still enough interest for C.Y. Lee to set part of his 1957 bestselling novel Flower Drum Song at the Forbidden City. Flower Drum Song became a hit Broadway musical by Rodgers and Hammerstein, and then an Academy Award winning film in 1961.

Charlie Low retired in 1962 and sold Forbidden City to feisty Coby Yee, who had been a headline act since the 1940s. Business, however, continued to plummet. The death knell was in 1964 when Carol Doda began dancing topless at the Condor Club in nearby North Beach. With the proliferation of topless and nude dancing, burlesque and variety clubs became passé. Forbidden City finally closed in 1970.

Many performers of the Chinatown nightclub circuit did end up in Hollywood films, Broadway, and television, but they were never able to break into the mainstream. With the racism of the period, they were always deemed ‘other’ and had to deal with heartbreaking statements like, “If it were not for their race, they would undoubtedly be headliners in New York’s Rainbow Room or some other first-line cabaret.” That’s what the Vancouver Herald printed after seeing Jadin Wong perform with an Asian-American dancer named Liang.

Most of the performers went on to other things after the end of the chop suey circuit. Larry Chin, the Sinatra crooner, became a truck driver. Noel Toy, the fan dancer, went into real estate. Many of the women retired from entertainment to raise a family. A few did remain in show business, most notably ballroom dancer Mai Tai Sing, who owned a nightclub in San Francisco for a while, and Jadin Wong, who became a manager for Asian-American talent.

Though the Chinatown nightclubs had to play up to a white audience looking for something exotic, they provided a first generation of Asian-American entertainers with a platform to show the world that they were more than just Oriental dolls or menial dishwashers. Seventy years later, it’s poignant to look at all these beautiful Asian-American faces in their glamorous gowns and svelte tuxedos, a window to a brief time when all these brilliant performers could shine.

About the Contributor