In Paris, there’s no lack of private art collections that have been transformed into museums, and even after more than a decade of living in this city, we’re still discovering under-the-radar cultural gems. The Musée Cognacq-Jay might be relatively small compared to, say, the Musée Nissim de Camondo, but the well-curated collection that awaits behind the doors of a 16th century townhouse on a quiet backstreet of the Marais allows visitors to step into the living room of two of the most important turn of the century art patrons.

Théodore-Ernest Cognacq and his wife Marie-Louise Jay were the founders of the Samaritan, the storied Parisian department store. (The two actually met while working as salespeople and climbed the economic ladder to eventually open their own store.) The two acquired most of their collection between 1885-1920. The current museum now boasts some 1,200 pieces of decorative items and fine art.

Cognacq bequeathed his acquisitions to the city of Paris upon his death in 1929. The collection was originally held in an annex building of the Samaritaine department store on Boulevard des Capucines, a design conceived by the couple. The collection moved to the Hôtel Donon (c. 1575) in 1990 and is now displayed across 20 panelled rooms in the styles of Louis XV and XVI.

The courtyard of the museum is worth a stop to rest before or after a visit to get a look at a structure that has had many uses in its almost 450-year history, including artisans workshops in the 19th century. The building was in ruin when the city acquired it in 1974. Classified as a historical monument in 1984, the exterior was renovated to its 16th-century glory, while features including the woodwork, flooring and fireplaces were brought from the original museum. Although it was not a totally smooth transition; the City of Paris decided to move the collection because the original Grandes Boulevards location was not considered part of Paris’s “cultural circuit,” but descendants of the Cognacq-Jay family disagreed, as they believed it went against their relatives’ wishes.

While some have complained that the new space is more cramped, the modest sized rooms are also ideal for showcasing the many small and household objects that make up the collection. Miniatures, boxes and sculptures are on display in staged rooms that have the intimacy of a salon.

Cognacq was inspired by the Intimist art movement that favoured domestic scenes and other everyday parts of life. The sorts of cabinets of curiosities include a perfume dispenser in the shape of a pistol, a musical box in the form of a harp and a “necessary box” filled with all the equipment to get through the day in the 18th century.

One can easily imagine going to sleep on the lush bed “à la Polonaise” (which was once housed in Versailles) or having a cocktail on a decorative canapé. Even if you can’t visit in person, you can take a virtual tour inside the intricate drawers of an 18th century mechanical table.

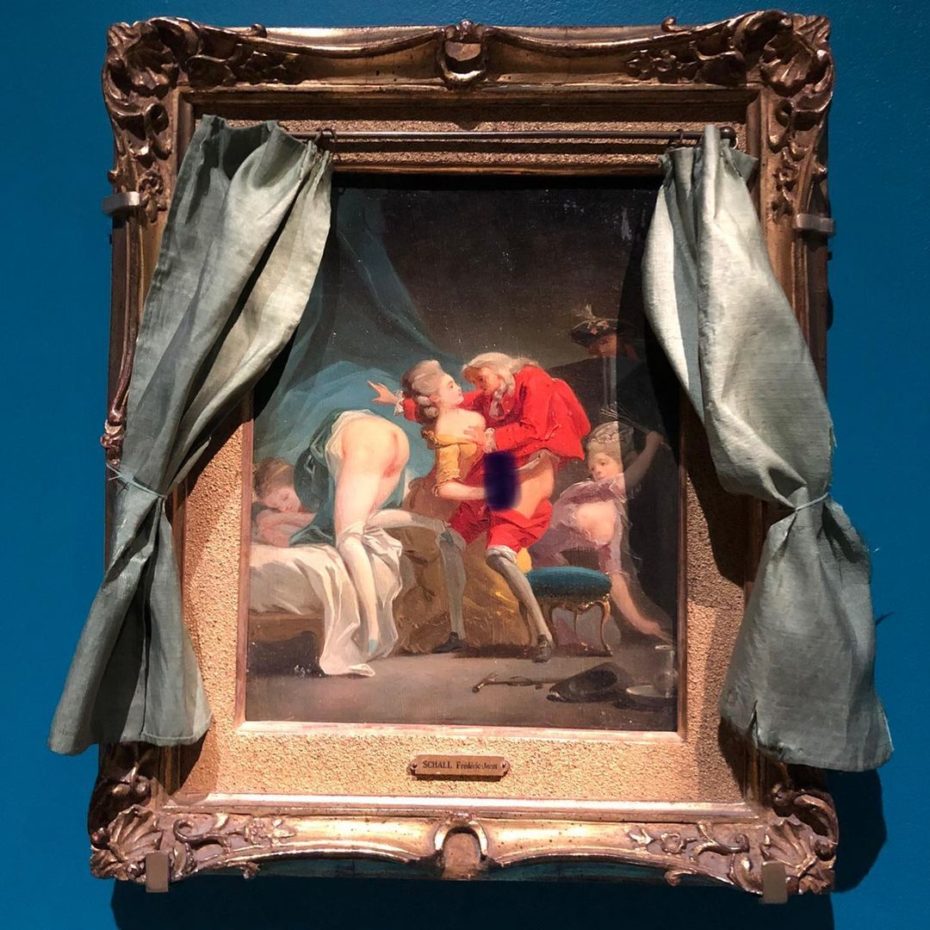

One painting that stands out among the collection is “Deux Jeunes Amies qui s’Embrassent” (“Two Young Female Friends Kissing”) by French painter Louis-Léopold Boilly. It’s a rare and early depiction of a lesbian encounter, but given the perspective from the painter, it comes off more voyeristic than Saphique. Last summer, the museum held an exposition dedicated to 18th century French eroticism in art.

The current temporary exhibit on Boilly includes many of the humorous trompe-l’œill techniques he pioneered. But given that Boilly arrived in Paris on the eve of the French Revolution, there’s also a certain political spirit to his paintings, as he explored the underbelly of society from a women’s prison to the rambunctious Boulevard du Crime.

The museum has also put an increased attention on the role of women during this period, as they have traditionally been overlooked. These include a painting by Élisabeth-Louise Vigée-Le Brun (she was Marie-Antoinette’s favorite portrait painter) and a portrait of British actress and singer Miss Frances Maria Kelly.

If you’re looking for household-name artists, the museum has got you covered too. Arguably the most notable painting in the collection is Rembrandt’s “Balaam and the Ass,” an early work by the Dutch master.

Outside of European pieces, the museum also includes notable examples of Chinese art, collected during a time of increased international trade and access to other cultures. Colourful bird statues including one of a phoenix bring liveliness to the dark wood-paneled rooms. Also don’t miss a turquoise porcelain cat that serves as a night lamp with the mouth and eyes being illuminated. The glazing technique, perfected by Chinese artisans and resulting in bright colors, was much admired by European collectors.

During the 18th century, there was also a revival of interest in Roman art after architectural digs discovered more artifacts from antiquity (most notably the identification of the towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum). This was also the era of the Grand Tour, when young, upper-class men traveled the continent to learn its history and cultures, as well as increased exchanges with the Ottoman Empire. The Musée Cognacq-Jay contains many contemporaneous interpretations of these classical styles, both in their own room and scattered around the museum. There are statues of Cybele, the mother of the gods in the ancient worlds, seated on a throne and of Venus by famed French sculptor François-Marie Poncet.

If you want to step inside a shrine to a Paris of the past, you can visit the Musée Cognacq-Jay from Tuesday to Sunday and the permanent collection is always free. It might not take you more than an hour or so to look through the collection, but be sure to take your time; there will definitely be more than meets the eye.

Written by Hannah Steinkopf-Frank