Never was there a weapon of more romance than poison. From the tragic double-suicide of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, back to the death of Socrates and even the more recent murky business surrounding the death of several Russian defectors under Putin’s reign, poison has fascinated everyone who has ever encountered it. For those mystified by its powers, curious about its history, or simply enthralled by its very existence, here’s a brief history of poisoning. Read on with caution…

Poison is a deadly tale as old as time. For as long as people have messed around with plants, poison has always been lurking below the surface, hidden within layers of curious chemical compounds. As Paracelsus, the father of toxicology once said, ‘poison is in everything, and no thing is without poison. The dosage makes it either a poison or a remedy’. So it really is a question of take your pick.

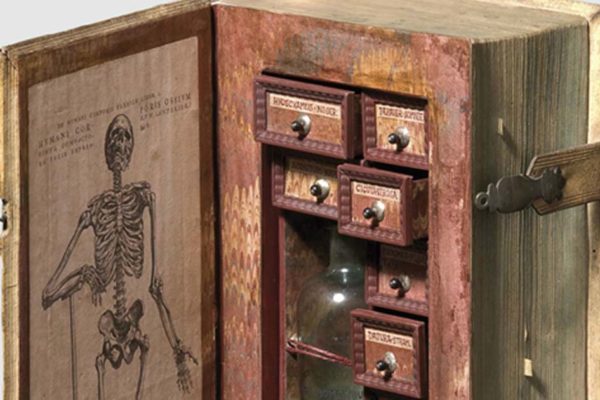

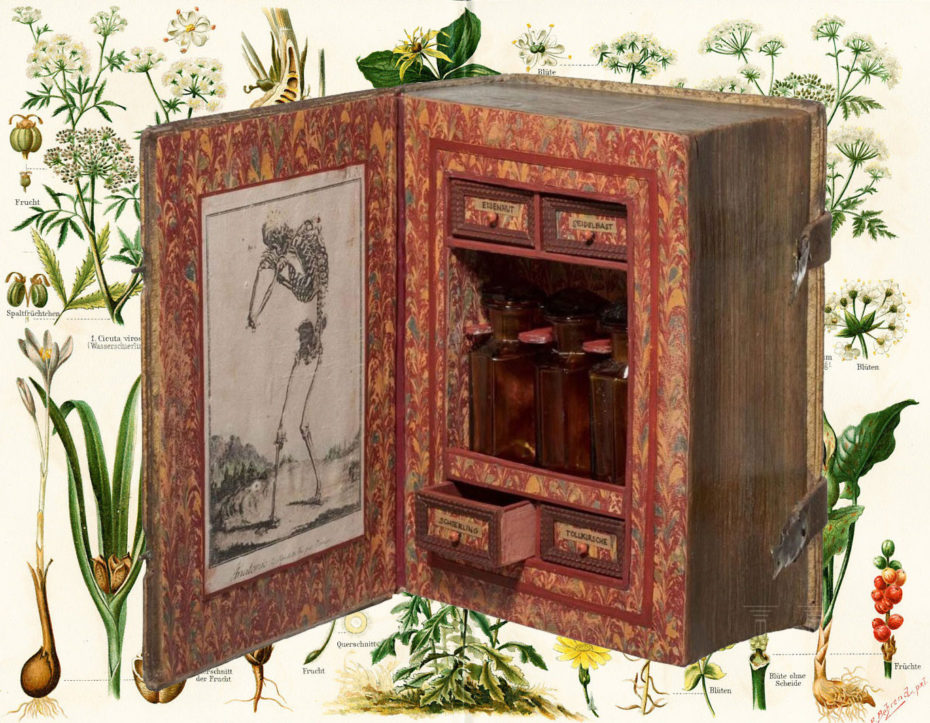

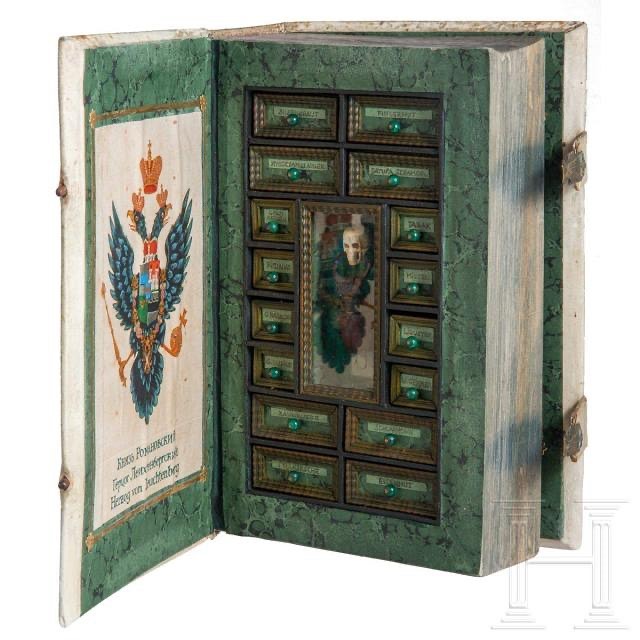

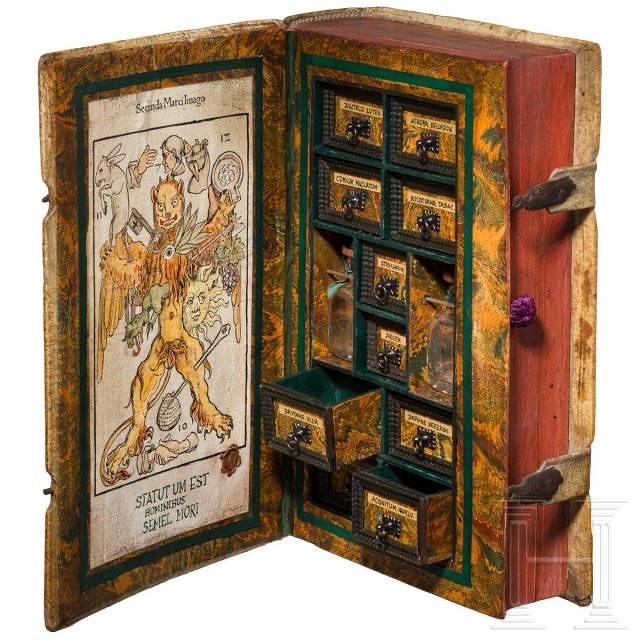

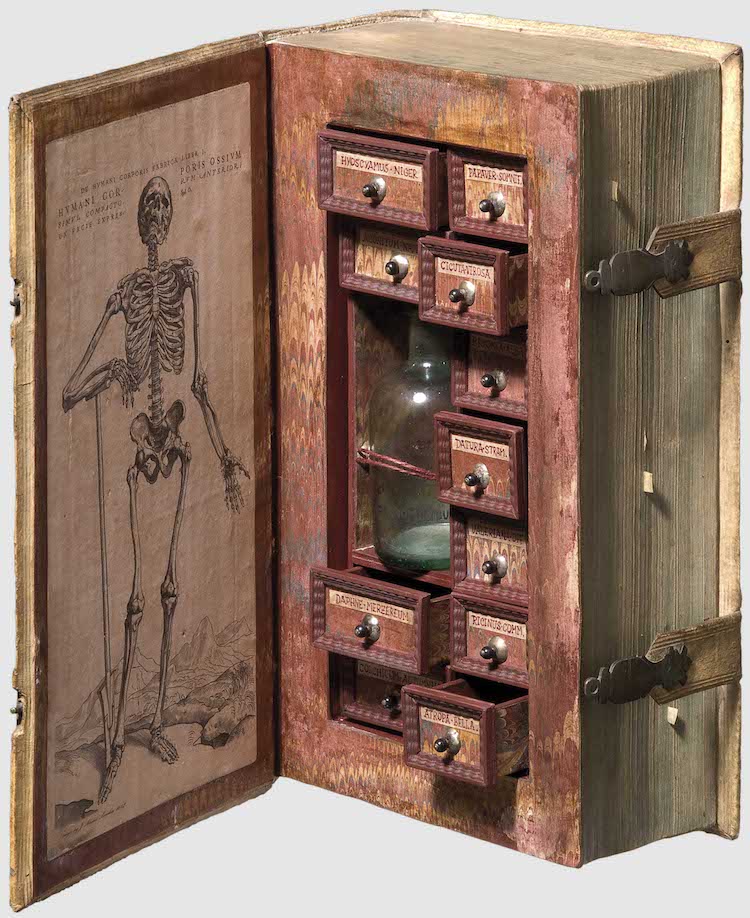

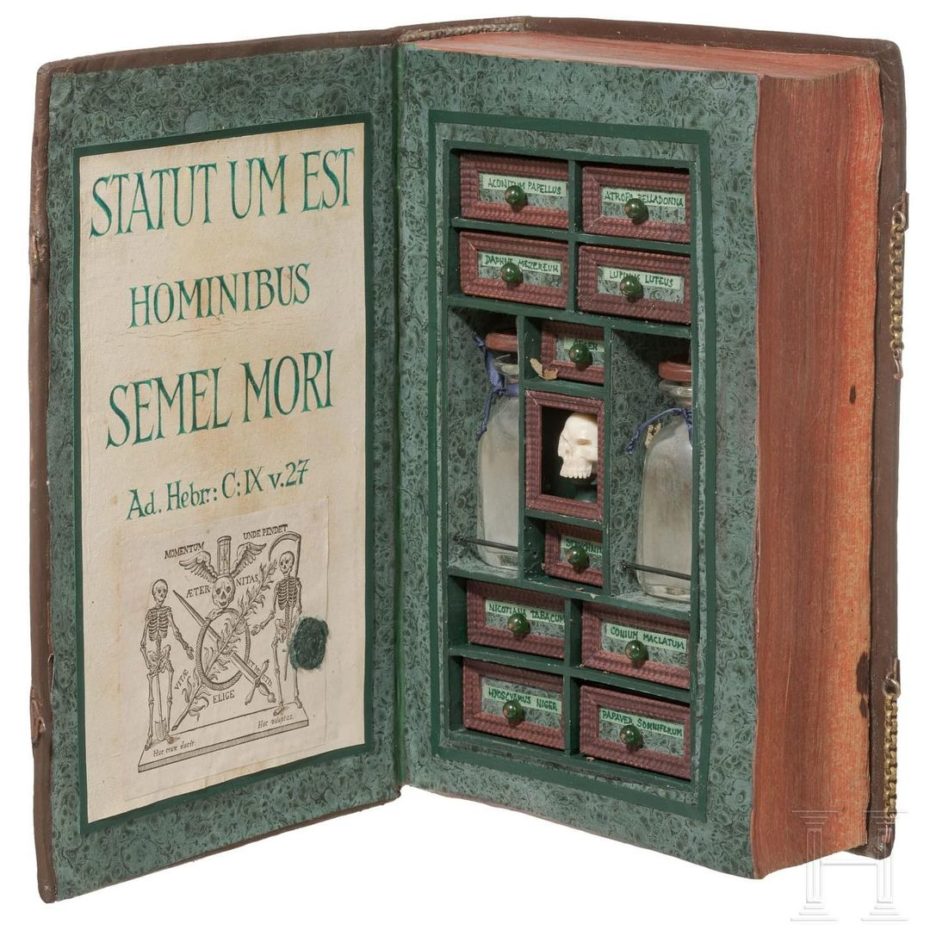

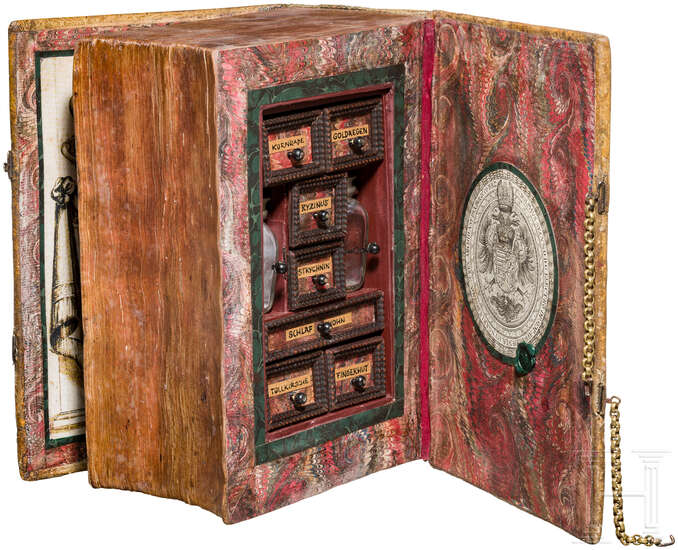

Perhaps secondary to administration and a killer plan, storage is an important factor to consider when it comes to managing your supply of the strong stuff. For example, precious necklaces and antique bijouterie require a proper jewellery box – you don’t want them getting all tangled up. The same goes for your prized collection of poisons, you know, the ones you bring out for special occasions. Folks with money love to have trinkets for incredibly specialised purposes, so why should the storage of poisons be exempt from this proclivity?

Back in the 1600s, poison cabinets were all the rage. Hollowed out books became secret hideaways for poisonous and medicinal plants. Complete with silver-knobbed drawers and meticulous labels, this particular cabinet (pictured above) that went to auction in 2008 would have contained everything from opium poppy, a well known narcotic which was previously used to cure upset stomachs, to belladonna, a poison responsible for killing several emperors’ wives during the Roman Empire, as well as warding off motion sickness. See, one man’s poison is another man’s medicine.

It’s unlikely that an assassin or habitual poisoner would own one of these alchemic art pieces. After all, when one’s poisons are so clearly labelled, and the memento mori skeleton is so ominously portrayed, due process would be a short order. Rather, these deceptive books are more so on the shelves of collectors from later generations who were so fascinated by the original contents that they added on a few extras over the years in homage to the picturesque history of poisoning.

For those who like to step beyond the dressing room table and bring out the bling, the pillbox ring is the perfect fit. Also known more unambiguously as the poison ring, behind the bezel is a tiny compartment for your toxic treasure, much like a locket. This type of jewellery originated in India, but soon made its way to Europe, and by the Middle Ages, they were used to hide relics of saints such as bone and teeth, while also being worn as a talisman for protection. Later, during the romantic Renaissance period, the jewellery was used to keep cologne, locks of hair and portraits of loved ones.

It didn’t take long for this type of ring to be used for more insidious purposes. A slight turn of hand could slip poison into an enemy’s food or drink, or facilitate the suicide of the wearer in order to preclude capture or torture. The Italian noblewoman Lucrezia Borgia was thought to be skilled at using poison rings to dispose of her political rivals, and, some say, her brother too.

In Italy to this day, pouring someone a drink whilst holding the bottle with the back of the hand facing downward, so as to let something drop from a ring bezel, is called versare alla traditora (“traitor’s way of pouring”) and is still considered offensive.

Mythical, fictional, deliberate or accidental, history has witnessed a whole host of notable poisonings, with the jury still out on some alleged incidents. In 1672, a rumour got around Versailles that a network of diviners, essentially early modern European pharmacists, had been supplying poison to thousands of citizens. Police were called to a break-in at the laboratory of a recently deceased army captain turned alchemist, Jean Baptiste Godin de Sainte-Croix. Presumed to have died as a result of exposure to his own lethal chemicals, he had left behind a number of clues that would launch an almighty witch hunt among the highest ranks of society. In a red leather trunk belonging to the army captain, a series of letters he had saved were found detailing dealings of poisonings that incriminated both himself and his lover, a married aristocrat by the name of Marie de Brinvilliers.

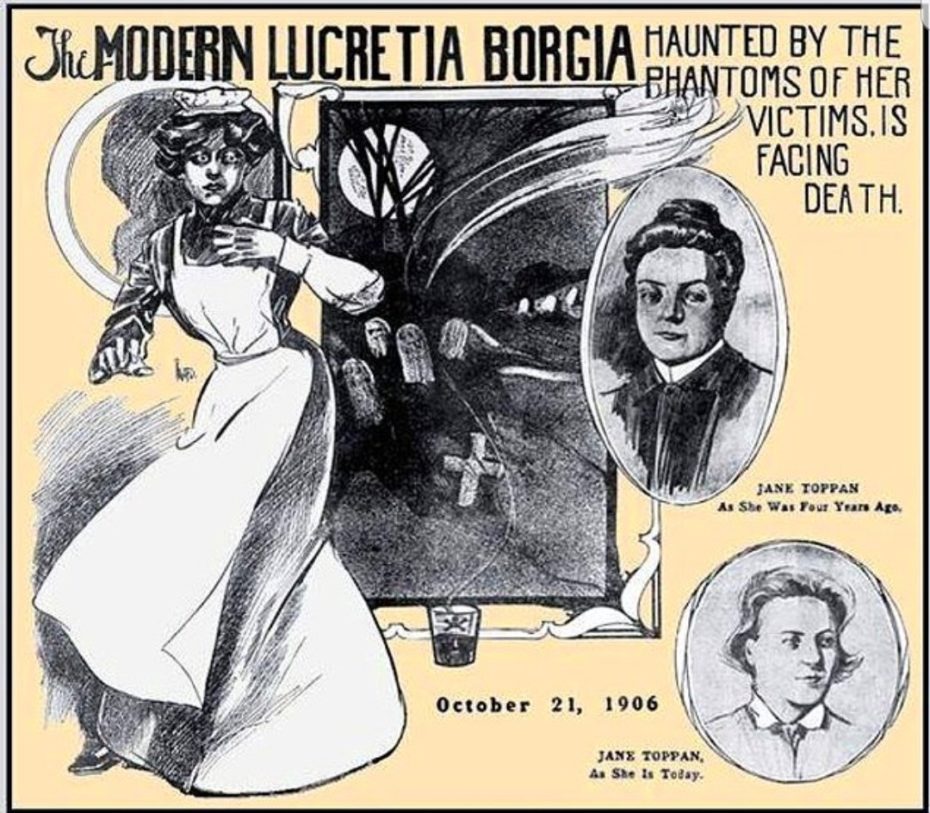

One of the simpler ways to hide poison in plain sight has been with a uniform. During the Gilded Age, Nurse Jane Toppan obtained morphine and atropine by legitimate means, and at first used it to ‘mercy-kill’ her severely ill victims. This power gradually escalated until she began using counteracting drugs to keep her favourite patients in the hospital with her, before morbid curiosity drove her to habitually experiment on helpless patients.

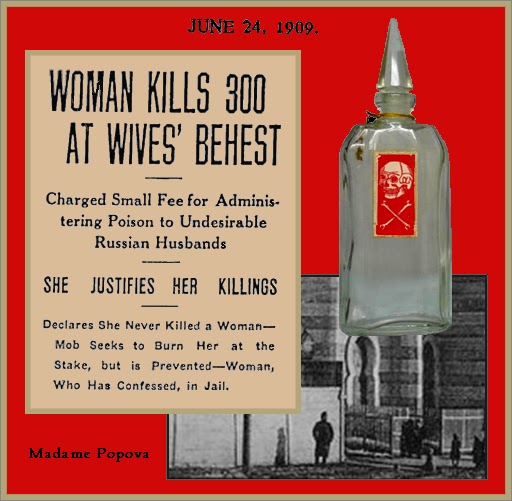

Also during the late 19th and early 20th century, Madame Popova operated a murder-for-hire service in Russia that specialized in liberating married women from their cruel husbands for a fee. She murdered over 300 men by making their acquaintance and then poisoning their food or drink. She was rescued from an angry mob and then put in front of a firing squad, where she stood unrepentant.

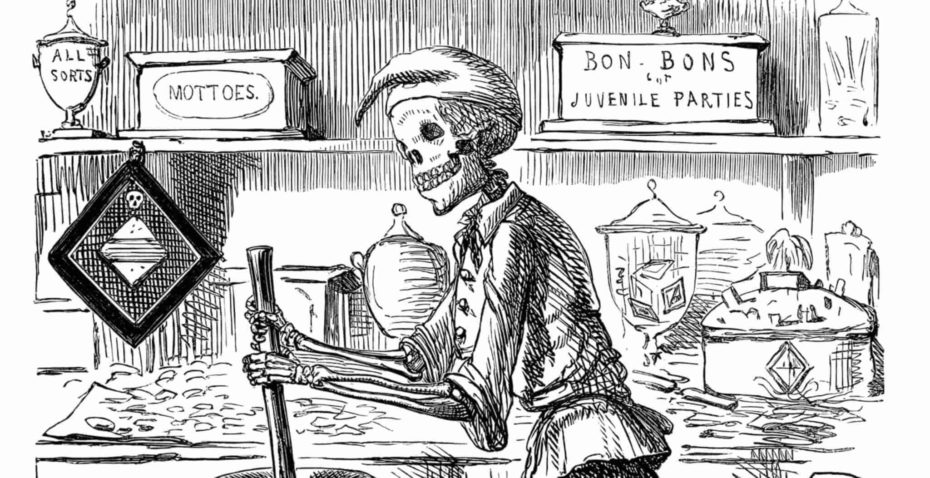

Sometimes, though, poisonings are tragically accidental. In 1858, more than 200 people were poisoned, and 21 killed, when a supplier accidentally sold the wrong cask of product to a candy vendor. Because sugar was expensive at the time, the vendor had taken to substituting some of the sugar for powdered gypsum. Only due to one fateful and careless exchange, a batch of peppermint humbugs were accidentally thinned with arsenic and promptly sold at the market stall. Of those who purchased and ate the sweets, 21 people died with a further 200 or so becoming severely ill with arsenic poisoning within a day. Known as the Bradford Sweets Poisoning, this accident eventually contributed to the regulatory Pharmacy Act in 1868 in the UK.

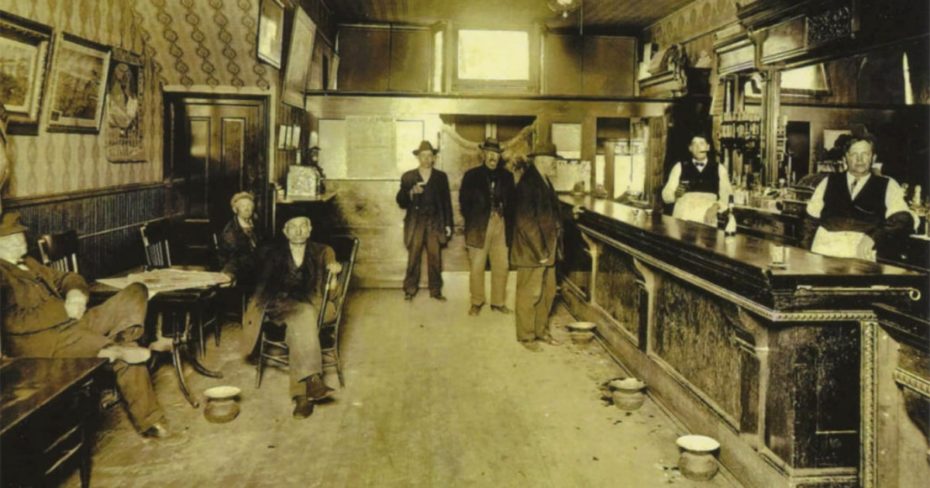

In the saloons of the Old West, unbeknownst to most, many whiskeys contained strychnine, a lethal poison most commonly used today as a pesticide, particularly for killing small vertebrates such as birds and rodents. However, diluted strychnine was thought to have curative effects, a belief reinforced by the fact that in many towns the poisoned whiskey was still safer to drink than the local available water. However, as historian C.W. Bayer writes, “when the pleasurable effects of the strychnine whiskey wore off, muscle spasms set in and the celebrant’s skin would crawl as if covered by dozens of baby tarantulas.” Or maybe that was just the hangover setting in. But get this – the highly toxic substance was also popularly used in small doses as an athletic performance enhancer and recreational stimulant in the late 19th century and early 20th century, due to its convulsant effects.

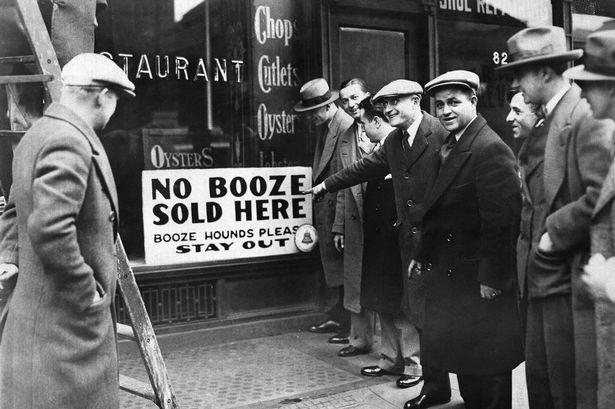

But it gets even worse. Remember that time the US Government intentionally poisoned alcohol in the 1920s? In an attempt to enforce Prohibition in 1920s America, the Prohibition Bureau deliberately spiked industrial alcohol with methanol, otherwise known as wood alcohol. With bootleggers turning to industrial alcohol to keep up with demand, suddenly, moonshine wasn’t just potent, it was deadly. On New Year’s Day in 1927, 41 people died at one hospital alone in NYC and it’s estimated the poisonings killed between 10,000 and 50,000 Americans. People like Wayne Wheeler, a US attorney and advocate of the temperance movement, attempted to justify the decision by arguing there was no obligation to protect the lives of citizens who broke the law by wanting to party.

During wartime, poison became one of the deadliest weapons. Although Roman Emperor Nero is believed to have used cyanide-containing cherry laurel water as a poison to dispose of unwanted family members, the chemical compound wasn’t formally discovered until 1782 by a Swedish compound who prepared it from the pigment Prussian blue. During the Franco-Prussian War in 1879, Napoleon III urged his troops to dip their bayonet tips in the poison and in 1915, German forces shocked Allied soldiers along the western front by firing more than 150 tons of lethal chlorine gas against two French colonial divisions at Ypres, Belgium. This was the first major gas attack by the Germans, and it devastated the Allied line.

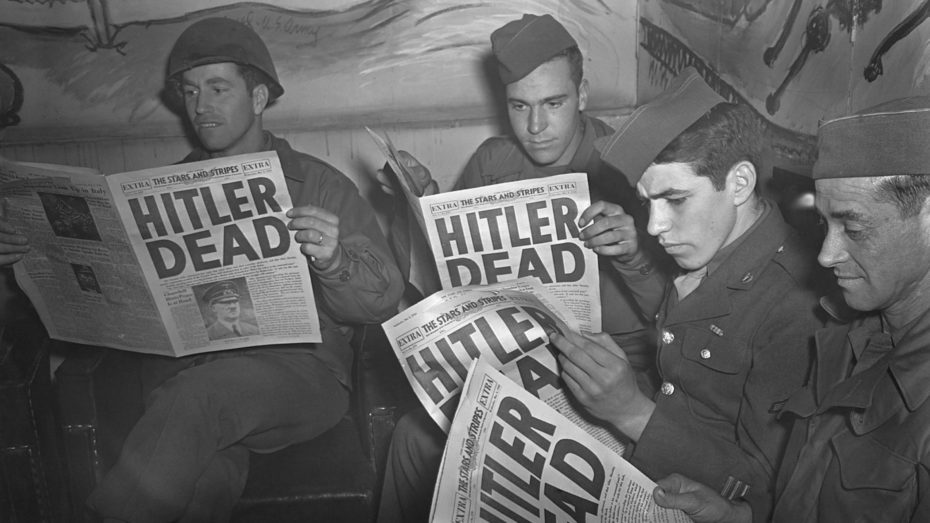

Then in World War II, unspeakable horrors were committed by the Nazis who used Zyklon B (cyanide) to commit mass murders in death camps. In the end, cyanide was used in mass suicides by the German people. Eva Braun bit into a cyanide capsule after her husband Adolf lost the second World War, and then shot himself in the head to avoid an inevitably gruesome death as the Red Army approached their safehouse. The Nazi propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels and his wife poisoned six of their children before biting into their own cyanide capsules shortly afterward.

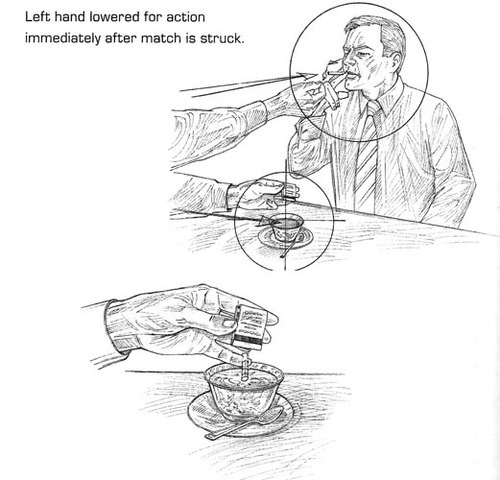

During the Cold War in the 1950s, the CIA hired a magician named John Mulholland to write a ‘magic book’ for spies; a manual on misdirection, concealment, and stagecraft. The highly classified document was thought lost after being destroyed in the 1970s, but recently, the manuals resurfaced when retired CIA officer Robert Wallace unearthed the extraordinary archived file in 2007 and made its contents available to the public. Complete with illustrations, the manual explained how spies could use skills like covert signalling and sleight of hand to poison an enemy’s drink and surreptitiously steal documents to complete their clandestine missions. The friendly gesture of lighting another person’s cigarette was ideal for covertly dropping a pill into the person’s drink. Mulholland’s work was commissioned as part of a larger secret CIA project called MkUltra to understand and counter claims that the Russians had mastered mind control and other unorthodox interrogation and surveillance techniques. In Robert Wallace’s own book, details how MkUltra chemists attempted to develop “invisible” inks and poisons derived from shellfish and cobra venom.

Caught in a sticky situation and looking for an antidote? Best to consult Mithridates the Great, I’m sure you’ve already got him on speed dial. Back in the 1st century BC, the Greek ruler concocted a semi-mythical remedy with no less than 65 ingredients to be used as an antidote for poisoning. It was one of the most complex and highly sought after drugs during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, particularly in Italy and France, where it was in continual use for centuries. So successful in fortifying bodies against poisons, that when Mithridates tried to kill himself, he could not find any poison that would have an effect, and, according to some legends, had to ask a soldier to run him through with a sword to finish the job. The recipe for the reputed antidote was found in his cabinet, written with his own hand.

No matter how greatly today’s poisonous history lesson has piqued your interest, we strongly suggest only getting involved with the pretty paraphernalia that housed poison, that and paracetamol.