Sarajevo might be quite unlike any other city in Europe. Nestled in a valley surrounded by the beautiful Dinaric Alps, it is a beguiling mix of old world cultures, where centuries of Ottoman Empire rule meet the grandeur and elegance of the Austro-Hungarian Hapsburgs. Wander through the maze of cobbled winding streets in the Old Town and you’ll discover crammed in amidst the ancient bazaars, synagogues, minarets and churches all within a stones throw of each other; Sarajevo is so breath taking you can see why it was named after the Turkish word for palace, ‘stray’.

The beauty of Sarajevo however, was put through the meat grinder of a civil war and the longest siege of any capital city in modern history. Orthodox Christian Serbs, Catholic Croats and Muslim Bosniaks, often friends and neighbours fought bitterly against each other following the break up of Yugoslavia. Between 1992 and 1995, Sarajevo became a city with no escape; wander through the city today and you will still come across bullet holes, bomb damage, abandoned ruins of a siege that lasted three times longer than the Battle of Stalingrad.

The main train station in Sarajevo, the željeznička stanica, is a hulking concrete remnant of the Communist era. Once luxurious steam trains passed through here en route from Vienna to Istanbul. Step outside and you’ll notice that the ‘Welcome to Sarajevo’ sign isn’t like most welcome signs you’ll find in a major European city. For a start it is stamped with the date ’84, but on closer inspection you’ll notice the rusting old sign is still pockmarked with bullet holes. The sign features a map of the city showing the Olympic venues and other points of interest, and it is easy to imagine people arriving at the train station and using the sign to plan out their day nearly forty years ago.

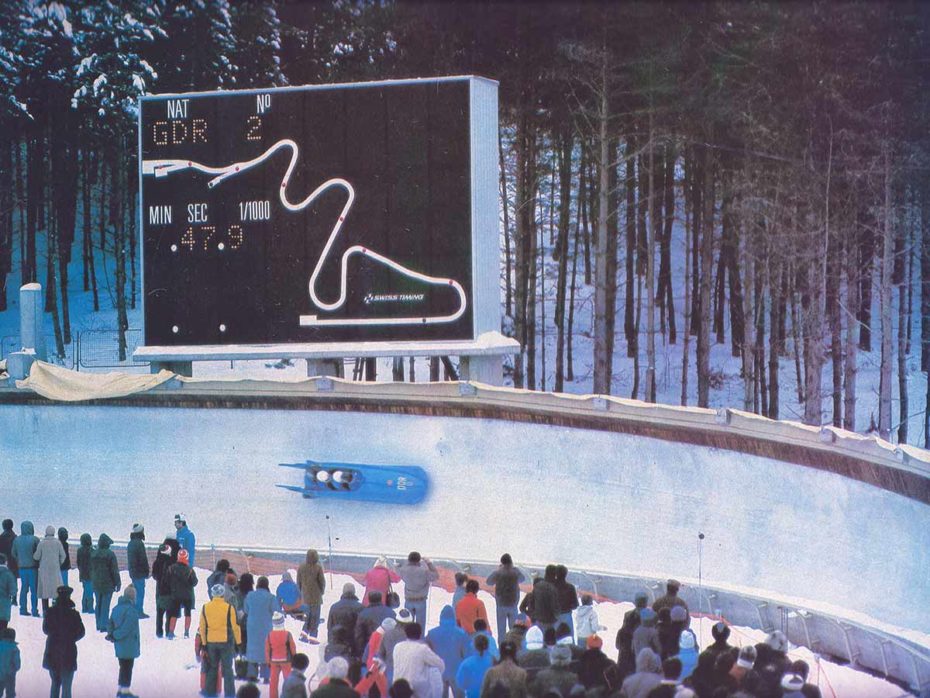

It is both a reminder of Sarajevo’s proudest moment; when they were the first Communist state to successfully host a Winter Olympics, and its most desperate; when the city was devastated by civil war just a few years later. To give a glimpse of what lay in store for Sarajevo, the skating arena where Jane Torvill and Christopher Dean’s ‘Balero’ routine would sweep the board with unprecedented 6.0s would soon be used as a morgue, the wooden seats torn up for coffins.

But this jewel of city in the Balkans has slowly been rebuilt – here is a guide to just some of the secrets of Sarajevo….

First pitstop in the morning is for coffee in Baščaršija, the old bazaar that dates back to the 16th century, and where the four centuries of Ottoman rule in Sarajevo is still most evident.

Bosnian coffee is fairly similar to Turkish coffee, but with a slight difference in when the water is added to the roasted grounds. It comes served in a small copper pot with a long handle, called a džezva, and placed on a copper tray, along with a glass of water, a handless small china cup, sugar cubes and a piece of rahat lokum; the Bosnian equivalent of Turkish delight. The local method is to break off a piece of sugar cube and place it on your tongue before each bitter sip.

Old coffee shops throng the ancient bazaar, which despite its tourist appeal, is still home to around 1,700 people who live in the cobbled streets that follow the natural slope down to the north bank of the Miljacka river.

Much of daily life in Baščaršija revolves around the leisurely outdoor seating in coffee houses such as Dibek, Divan Saraj and Caffee Divan. Explore the alleyways of this historic neighbourhood and you’ll discover traditional hand hammered metal work shops alongside the Sebilj ornate wooden fountain and the 16th century Gazi Hüsrev Bey Camii mosque.

Continue your wanderings south towards the river and you’ll come across perhaps the most important street corner in modern history. It was here, where the Latin Bridge meets the road Obala Kulina Bana, that Gavrilo Princip assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sofia on June 28th, 1914. Decades before, the German ‘Iron Chancellor’, Otto Von Bismarck made the prescient comment that,”If there is ever another war in Europe, it will come out of some damned silly thing in the Balkans.”

A Bosnian Serb, Gavrilo Princip was just nineteen years old when he triggered the chain of events that would lead to the outbreak of the First World War. He was part of a secret society that aimed to free Bosnia from Austrian rule. “I am a Yugoslav nationalist, aiming for the unification of all Yugoslavs, and I do not care what form of state, but it must be free from Austria,” claimed the teenager at his trial. The consequences would be staggering: not just the millions of lives lost in the Great War and the destruction of Europe’s old empires, but the aftermath of World War One would lead directly to the Second World War and the Cold War in a cataclysmic chain reaction that is marked by a simple plaque placed into a wall by the corner of the Latin Bridge.

Sarajevo is a city best explored by walking. But as you do, it is hard to escape the reminders of the siege. Many of the buildings are still beaten by the scars of modern warfare. When Bosnia and Herzegovina received international recognition as an independent nation on April 6th, 1992, the first Bosnian Serb shells fell on the city that same day. Surrounded by mountains, Sarajevo was swiftly cut off, and for 1,425 days Bosnian Serbs laid siege to the city with constant sniper fire and over three hundred artillery shells a day. Walk through the city and you will come across impact craters still in the pavement, which have since been painted bright red in memory of the 11,541 people killed, and due to their resemblance are known as Sarajevo Roses.

To get a powerful sense of what daily life was like as the incendiary shells rained down everyday, head toward the airport and a small suburban house in the Butmir neighbourhood. Descend down into the basement of a nondescript house and you’ll find part of an incredible tunnel that was the lifeblood of Sarajevo during the siege. The ‘Tunel Spasa’ was built painstakingly by hand in the spring of 1993 and led from a garage in the surrounded city, underneath the international airport runway and into the basement of a house in an area controlled by the United Nations troops.

Workers on the secret tunnel were paid one pack of cigarettes a day to build the underground lifeline that when it was finished, took two hours to get through. Food, medical supplies and ammunition would pass through here to the desperate citizens of Sarajevo. Germany installed communication lines so Sarajevo could stay connected to the outside world. The tunnel is tiny, lined with wooden boards and is a sobering reminder of life in Sarajevo as the lethal ring around the city began to tighten.

Look at photographs taken during the siege and images from the 1984 Winter Olympics taken just a few year before, and the contrast is staggering. Scottish photographer Jim Marshall is based in Bosnia and Herzegovina and took an incredible series of before and after photos of the city, which you can find in the excellent People’s Museum.

The 1984 Winter Olympics were the first to be held in a Communist State, and what was then still Yugoslavia, were exceptional hosts. But like other Olympic sites – Beijing, Berlin, Athens – many of the games’ sites lie in ruins. On the mountainside overlooking Sarajevo you can still explore the abandoned ruins of the ski jumps, podiums, and most impressively of all, the opportunity to walk along the decaying bobsleigh track.

And like much of Sarajevo, the memories of the war can still be found: the concrete track was used as a vantage point for Bosnian Serb snipers to fire on the city below, and you can still see the holes they made in the track to place their rifles. The best way to explore the Olympic ruins and other remnants of the siege is with the excellent local tour company Meet Bosnia.

After a long day’s exploring, there is nothing finer than a traditional Bosniak dinner in the old town. A particular favourite is ‘Galatasaray‘, owned by a legendary Bosnia and Herzegovina footballer Tarik Hodžić. Tucked away on Gazi Husrev-Begova, you’ll find the hearty welcome from the owner is matched by large plates of three types of meat, including the famous Bosnian Ćevapi sausages.

Bosnia is famous for its smoked meat and various veal recipes, which you’ll find in abundance at Dveri. Decorated in a rustic style, tucked away in an alley of the old town, it’s a charming place to sample traditional Bosnian cuisine and enjoy homemade bread and local wines.

In a quieter part of town off the beaten path, Avlija (meaning courtyard) is a bohemian family bistro enclosed within the home of the owner. We highly recommend their wings as well as dumplings with kajmak.

Sarajevo is also home to two of the most unusually decorated bars to be found in south eastern Europe. Caffee Tito on Zmaja od Bosna is a cafe and bar dedicated to President Josip Broz Tito, who led the Yugoslavian Partisan resistance during World War II, and ruled Yugoslavia until his death in 1980. Every inch of the walls of Caffee Tito are bizarrely decorated with weapons, portraits, flags and sculptures of the former national hero. The beer garden outside comes complete with abandoned tanks and other military vehicles.

Almost the polar opposite in terms of decor is the wonderful Zlatna Ribica on Kaptol, near the Vječna Vatra eternal flame war memorial. Step inside to discover an Art Nouveau treasure trove of antiques, chandeliers and cosy tables filled with an endless array of forgotten relics to explore over well made cocktails.

Bosnia and Herzegovina is rarely mentioned in the international news these days, the civil war all but forgotten except for those who had to live through the violent disintegration of the old Yugoslavia. We spoke to one bar tender in a tiny place in Sarajevo’s old town, who was a sniper during the siege at the age of just fourteen. Cross the Vrbanja Bridge in the middle of the city which thirty years ago, was no man’s land, and you’ll be standing on a spot which perhaps sums up the complex and troubled history of Sarajevo. It was here that Bosko Brkic, a Serb, was shot by a sniper alongside his Muslim girlfriend Admira Ismic as they tried to escape the city. American photojournalist Mark H. Milstein captured the moment the childhood sweethearts died locked in each others arms, as they became known as the ‘Romeo and Juliet in Sarajevo.’

Still today, tensions loom large, and Bosnia and Herzegovina might be the only country in the world that has three ruling Presidents at once, one from each of the three major ethnic groups. As far as historic European capital cities go, Sarajevo clearly doesn’t draw the same crowds as Paris, London and Rome, but despite its complicated recent history, it remains a unique mix of ancient Ottoman culture, old European aristocracy, with a veneer of Communist brutalism, that have led some people call Sarajevo the ‘Jerusalem of the Balkans’; or as Admira Ismic wrote in a letter to Bosko Brkic, “My dear love. Sarajevo at night is the most beautiful thing in the world.”