We have all heard of Amelia Earhart, breaking records as the first woman to fly across the Atlantic Ocean, but where did the inspiration for her aviation adventure come from? Two decades earlier, the lesser known but equally high-flying Harriet Quimby blazed the trail and proved cockpits aren’t just for men. In 1911, she became the first licensed American female pilot, and went on to be the first person to fly at night and cross the English Channel. All accomplished in style might we add, in a fiercely fashionable purple satin jumpsuit. Harriet spread her wings and enjoyed success in other male-dominated arenas outside of aviation too, albeit with a little turbulence along the way. Strap in for take off!

Harriet was born a farmer’s daughter in 1875, and later became a Cali teen when her family left the farm and relocated to San Francisco. Like many little girls, her first dream was to be an actress and after high school she set her sights on the stage. Harriet’s striking beauty landed her some modelling gigs as well as a small role in a film, but it was her quick wit and sharp mind that proved her true calling was behind the camera as a writer.

In the early 1900s, Harriet worked at local newspapers on the West Coast before moving to New York to be a theatre critic and photo journalist, at the time two very male-dominated professions. Born with a natural passion for new technologies, she was one of the first journalists to adopt the use of a typewriter. In New York, life was a whirlwind of social events and travel. While Harriet’s peers were financially dependent on husbands or relegated to the home, Harriet supported herself with her own apartment and was often seen smoking and zipping around town in her flamboyant yellow car.

It was during a chance work assignment covering an international aviation tournament in 1910 that Harriet’s fascination with flight began. It was here too where she first met her future best mate Matilde Moisant, a fellow adventurous, unmarried 30-something woman. Matilde’s family owned an aviation school in Long Island. Cogs started turning in the mind of the never off-duty outgoing journalist who thought flight lessons would make for an interesting article, so off she went, arm in arm with her newfound fearless friend.

Just four months and thirty-three lessons later, in 1911 Harriet became the first woman to receive a pilot’s license in America. Matilde soon followed and became the second.

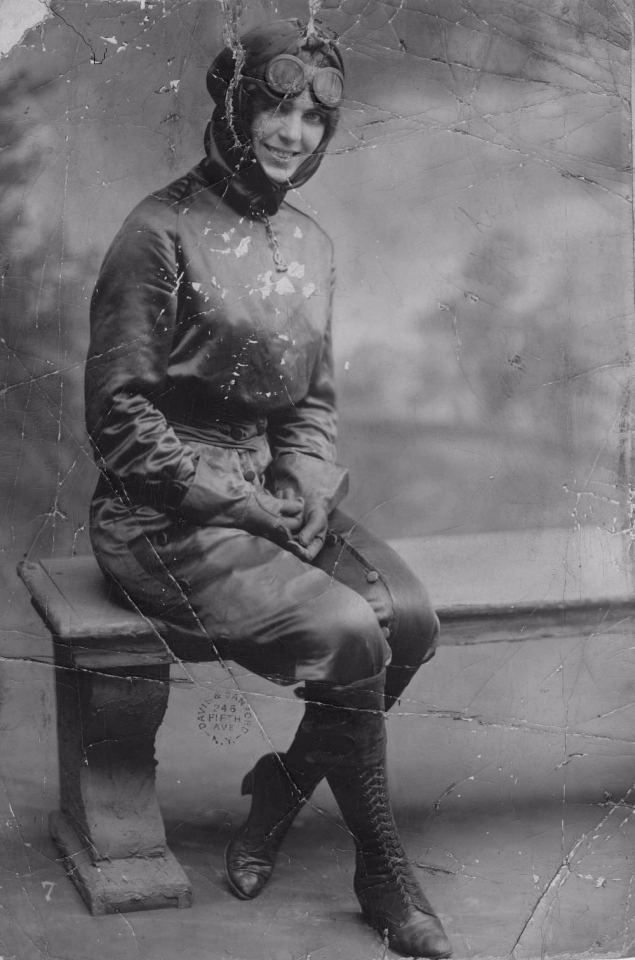

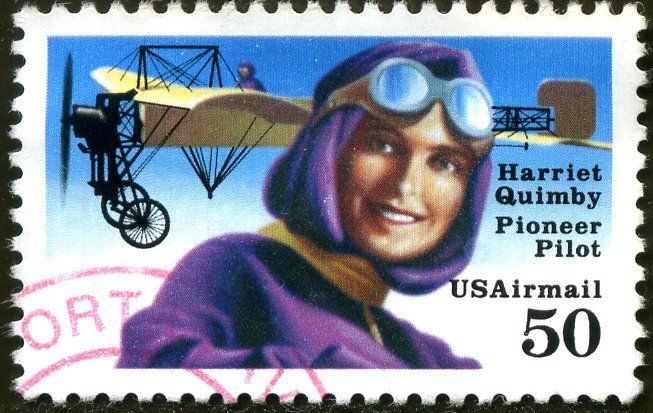

Immediately after receiving her license, Harriet would turn heads for a different reason. She ditched impractical petticoats and instead designed a suave purple satin aviation suit which she paired with antique jewellery and high laced boots. Her signature look. Helped by her connections in journalism, she became a media darling and was nicknamed the ‘China Doll’ by the press who focused on her slender stature, blue eyes and fair skin more than her flying. Although male pilots didn’t receive this type of objectification, she capitalised on her popularity and was often sought out for lucrative high profile spectator events.

Harriet used her newspaper column to encourage other women to take up this daredevil profession, describing it as a ‘fruitful occupation’. She said, ‘male flyers have given the impression that aeroplaning is very perilous work, something an ordinary mortal should not dream of attempting. But when I saw how easy [they] handle their machines, I said I could fly. Flying is a fine, dignified sport for women, healthy and stimulating for the mind, and there is no reason to be afraid so long as one is careful.’ If flying wasn’t for you, she also advocated for women to learn to drive and fix cars.

Harriet competed day and night in airplane races around the country, showcasing her talent and earning thousands of dollars at a time for each performance. At the end of 1911 she was asked to participate in President Madero’s inauguration in Mexico City. It was here that Harriet got the idea to fly across the English Channel.

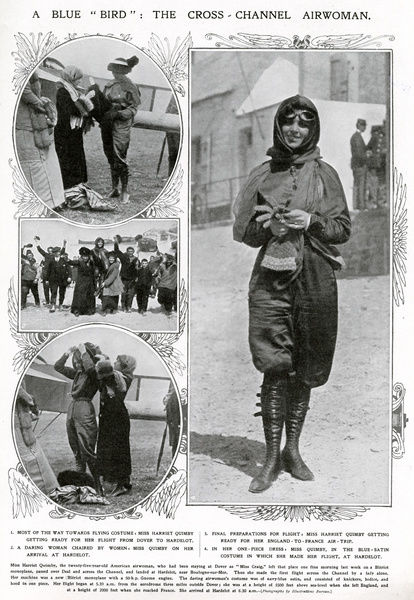

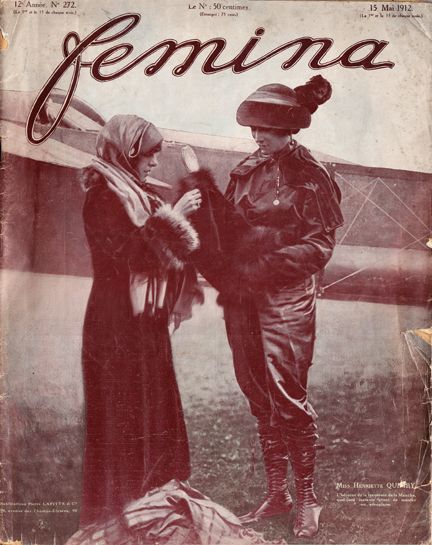

While the distance may not seem like much today, crossing the English Channel, or any large body of water, was a legitimate feat of aviation at that time; planes of that era were not known for being especially reliable or safe. There was no radar or GPS to track your position, communication with the ground was crude at best, navigational aids were non existent and the idea of possibly being thrown off course over an open ocean in the earliest of aircrafts was wildly dangerous. So much so that her friend and fellow pilot, Gustav Hamil, offered to make the flight in her place and even don her purple jumpsuit to fool journalists out of concern for her life. Never one to run from a challenge, Harriet turned down his offer, and made the flight without incident, becoming the first woman to successfully fly over the Channel in 1912. Despite this huge achievement, the feat was overshadowed by the sinking of the Titanic which happened the day before and dominated headlines.

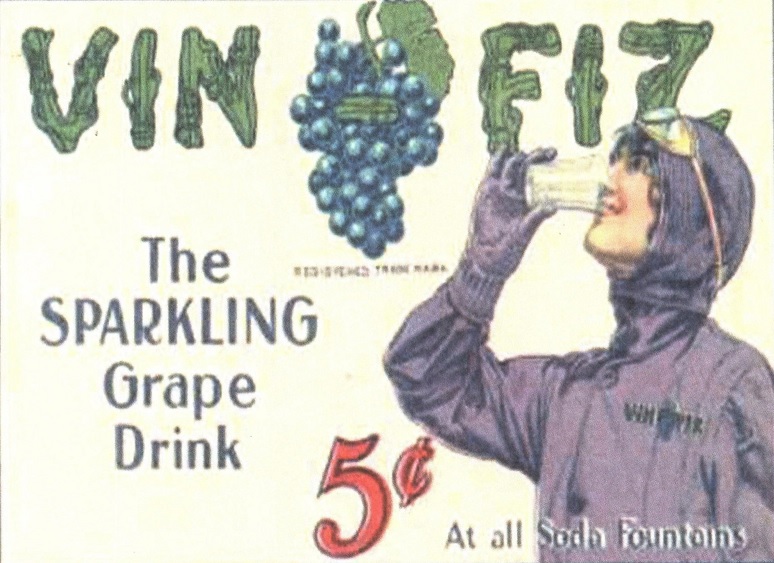

Harriet played the media game well and thanks to her writing skills and feminine touch, particularly that unforgettable jumpsuit, she penned seven screenplays that were made into silent film shorts and graced many a glossy magazine cover. As the queen of branding, she continued with her trademark purple reign and became the face of a new grape soda, Vin Fizz.

On July 1st 1912, Harriet’s whirlwind life and dazzling short-lived aviation career came to a grounding halt when she made her last flight at the Annual Boston Aviation Meet in Massachusetts. At 1000 feet high in the sky, the aircraft unexpectedly pitched forward, ejecting Harriet from her seat and to her death, aged 37. In a sealed secret note to her parents found afterwards, she had written, ‘if the worst happened, I will have met my fate rejoicing’.

Better known female pilots have come to dominate the narrative of women in aviation, but Harriet should be remembered as a pioneering aviatrix and a fearless modern woman who, well before the roaring twenties kicked in, was often found smoking cigars and drinking the boys under the table before running rings around them in the sky.