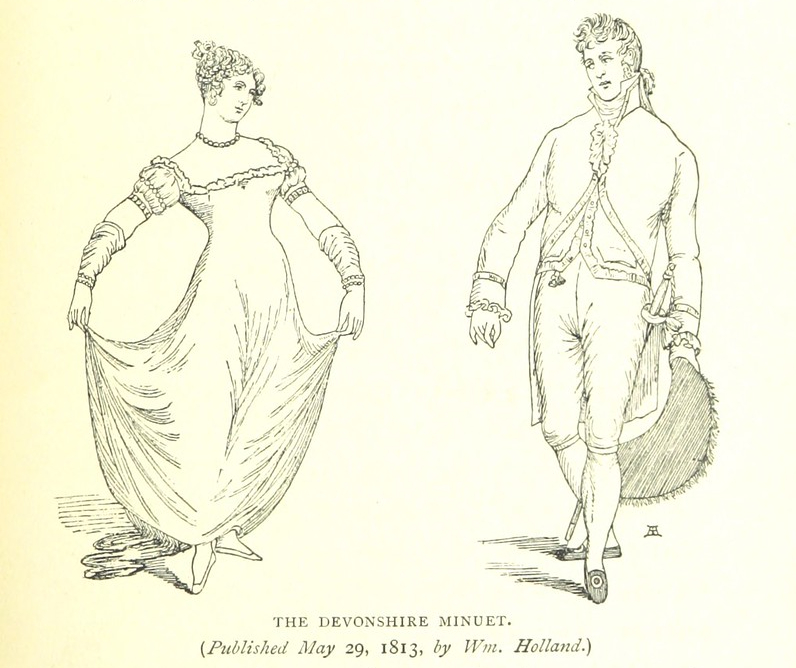

Just what the deuce do they mean with all their gadzooks and apoplexies, their barouches and barking irons? The language of the Regency – the period of time roughly earmarked as 1795 to 1820 in Britain when the reigning King George III was deemed unfit to rule and his son took over as Prince Regent – was as varied, sharp-witted, and creative as any of the slang being formed today. This was especially so amongst the uppercrust – the crème de la crème, one might say – of British society in the early 1800s, fondly known amongst its members, or anyone who has been watching Bridgerton, as the ton.

Ton is a shortened form of the French phrase le bon ton, meaning ‘good manners’ or ‘good form’ (for a definition of Bad Form, very much anti-Ton, see below), characteristics held as ideal amongst this very exclusive club of Earls and Ladies, Barons and Duchesses. Their social hierarchy was rigid and unforgiving, and to be a member was to play a very careful game, a game usually played at Almack’s, London’s most exclusive social club. Just as when playing the ‘change – the buying and selling of stocks – a misstep here could be painful.

The language of the ton could be just as complex as its dance of etiquette, so here’s a brief guide as to what exactly they’re all going on about to prepare you for this season of Bridgerton, your next Georgette Heyer, or your re-read of Austen. Allonsy!

Venetian Breakfast

We’ll start with a confusing one. A Venetian Breakfast did not, in fact, occur at breakfast. Instead, it was afternoon event that would often last long into the evening. The decadence of it may very well be how it received its name, as Venice was known for its excesses and debauchery, its determination to seek out and revel in pleasure.

Vowels

To give someone vowels was to give them an I.O.U. As today, these were not necessarily enforceable by law and were rather debts of honour. Despite this, many gambling clubs – or hells – had agents who would write out I.O.U’s, signed, witnessed and stamped, and these were considered as de facto legal debts – at least they were to the men of the ton, where to refuse to pay your vowels was to put your honour at stake.

Phaeton

This one will be familiar to those who have either read Pride and Prejudice or watched the 2005 adaptation, in which the infamous Mr Collins tells Elizabeth of how the daughter of the esteemed Lady Catherine De Bourgh often “condescends to drive by in her little Phaeton, and ponies.” But what, exactly, is a Phaeton? A carriage of some kind, we can deduce. But what type? How does it differ from say, a curricle (light, owner-driven, with two horses and wheels) or a gig (also light and owner-driven, with two wheels but only one horse – often to be found in Regency romances being driven at high speed across the Highlands by confirmed rakes)? There were various types of Phaetons, but they all had four wheels. The Phaeton Mr Collins speaks of is one driven by two ponies, often lightweight, pretty things that were used by young ladies in parks, and not for journeys of any considerable distance. As for curricle gigs and gig curricles, we’ll leave that for another day…

Dowager

Now, we’ve all heard this one at some point. It’s usually used in a mildly pejorative sort of way to describe an elderly woman with wealth or strong dignity, but what are the actual prerequisites to be officially termed a dowager? In short, a dowager is a widow who holds a title or property derived from her deceased husband. If she held a title, such as Countess, it was common for her to continue using it after her husband’s death, provided that she prefix it with ‘dowager’, such as Dowager Countess of Loamshire.

So, it seems, not all dowagers are made equal.

On Dit

From the French, meaning “It is said.” Usually used in the phrase, “the latest on dit.” In short: gossip. The Regency equivalent of saying, “And that’s the tea.”

The Cut

The Cut is about renouncing one’s acquaintance, but really it needs its own subcategories – just as in the butchers, you’ll find that there is more than one type of cut to be had. There is the Cut Direct, the most brutal of the Four Cardinal Cuts – or so I call them – which is to stare someone in the face and pretend not to know them, and then there is the Cut Indirect, which is to look away and pretend not to have seen. My favourite, the sweet-sounding Cut Sublime, is to admire some far away thing – the clouds, say – until the offender has passed by. To deliver the Cut Infernal, on the other hand, is to lean down and adjust your shoes until the meeting has been avoided.

Blazes, the Regency heroine cries, these knives are sharp.

Bad Form

In early 19th century England, to accuse someone of having bad form could be in jest, as when something is considered a #fail today, or it could be more serious, as when implying that something was below the belt.

“I say, Billingsby, that was bad form.”

A true gentleman would never!

At Sixes and Sevens

This means to be confused, but why? Like many etymological wonders, no one is entirely sure. Its most likely origin is thought to be the game Hazard, where to set on the numbers six and seven was considered the most risky, and therefore to do so one must be in a careless or confused state. Makes sense, I like it.

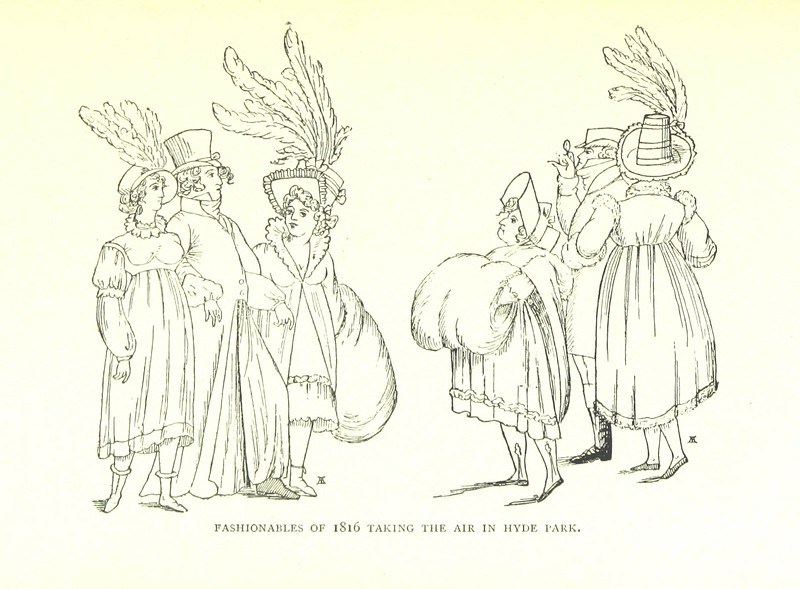

Corinthian

The epitome of the well-dressed sporting gentleman, of either the turf or the ring. So called because of their resemblance, I suppose, to that fine order of architecture. A Corinthian didn’t do any sporting endeavour by half, whereas a dandy, when riding to hounds, would not pass the first field for fear of muddying his boots.

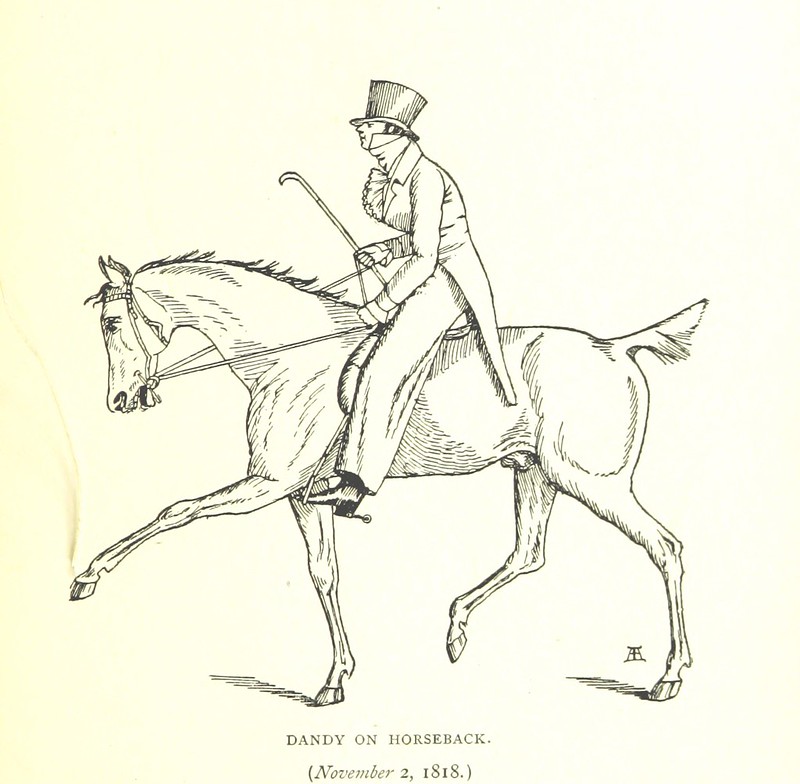

Dandy

Though Thomas Carlyle once wrote that “others dress to live,” whereas a dandy “lives to dress”, there’s more to being a dandy than caring about your appearance. Charles Baudelaire defined it as being someone who “elevates aesthetics to a living religion”, and that “these beings have no other status, but that of cultivating the idea of beauty in their own persons, of satisfying their passions, of feeling and thinking…Dandyism is a form of Romanticism.” Being a dandy wasn’t relegated to the upper-classes, either. George Brummell, a famous dandy, was of the fake-it-til-you-make-it set, with no aristocratic background. His greatness, it is said, was “based on nothing at all.” A precursor to the celebrity, Brummell was famous for being famous. And what kind of pleasure does a dandy derive from his dandyism? “Solely,” Carlyle says, “that you would recognise his existence; would admit him to be a living object; or even failing this, a visual object, or thing that will reflect rays of light…”

Chatelaine

As covered by MessyNessyChic in this article, a chatelaine was essentially a wearable What’s in My Bag video by Vogue. A kind of tool belt, the chatelaine held an array of both useful household appendages and fanciful items on a series of chains. A châtelaine was originally the mistress of a chateau, who would typically keep all the keys to the household’s many locked doors, cabinets, pantries, desks and drawers. A more everyday version of this would be the reticule, a small bag kept on a women’s person, also known by some as a ‘ridicule’ due to its occasionally gaudy nature, as of that carried by the vulgar Mrs. Eton in Austen’s Emma.

Cheltenham Tragedy*

To make a big deal out of something is to make a Cheltenham Tragedy out of it.

*This is a phrase used time and time again in Regency romances but is not, in fact, authentic to the era. It is widely believed to be a Heyerism, words and phrases co-opted by the original Regency romance author Georgette Heyer in her many, many novels of the genre, from The Reluctant Widow to The Nonesuch. It’s thought she did this as a means to prevent and easily prove plagiarisms of her work – not dissimilar to the use of ‘trap streets’ by cartographers. Some researchers even think she went so far as to take genuine Regency terms from dictionaries, like Grose’s 1811 Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, and then used them for opposite meanings.

Nonesuch

Speaking of Heyer’s novel, The Nonesuch, what, I hear you ask, is it? If you’ve been watching Bridgerton, you’ll be familiar with the terms ‘diamond of the first water’ and the ‘incomparable’ of the season. The Nonesuch – sometimes also a Nonpareil – is the male equivalent. He excels at most things in life, and is often the victim, like the Duke of Hastings, of the mamas of the ton when they go out hunting.

Deuce

We’ll draw this odyssey of education to a close with a word you’ll find plastered all over any Regency romance, and a word you’ll have often found yourself muttering before having read this guide. A late 17th century alternative to swearing, similar in meaning to ‘devil’, ‘damn’, or ‘cursed’, deuce (or deuced) comes from rolling a two in dice, the lowest possible score, and refers to less-than-ideal things, or a sense of frustration in something.

“What the deuce does it mean?!” said no-one, having now been brought up to speed on how to tattle like the ton.

It was our pleasure.