You’re looking at a very rare portrait from 1650 depicting a Black woman and a White woman, both appearing to hold equal status, some 183 years before the abolition of slavery act. Curiously, rather than commenting on the race debate in 17th century Britain via the uncommon pairing, the anonymous artist chose to write an inscription (see the faint black script above the two women) declaring that wearing beauty patches is “a sin of pride”. The cosmetic trend peaked in the 18th century, but not before it turned precedent on its head. Two centuries earlier, any kind of distinctive mole or facial marking – far less a face covered in esoteric beauty patches – would’ve been considered ‘the work of the devil’ and elicited accusations of witchcraft followed by a burning at the stake. Suddenly, cosmetics were being explored with abandon and beauty patches became an essential fashion accessory of the landed aristocracy and the politically powerful. As with most fashion trends throughout history, not everyone was a fan. In fact, the very same year the “Allegorical Painting of Two Ladies” was made, the English and Puritan parliament went as far as to legislate against the use of beauty patches, which they condemned as an ‘immoral vice’.

Also referred to as a mouche or fly (insect) by the French, the beauty spot was a very small, often distinctively shaped fabric patch that was applied to the face or exposed upper body, and was solely applied for the purpose of inviting attention. An essential and required part of high society dress, mouches were worn by both sexes, but women seem to have indulged in the trend rather more than men. The display of pale, marble-white, if not anaemic skin was essential for the 18th century upper classes in society to demonstrate they had never been exposed to a harsh environment, let alone engaged in manual labour. This idle culture created the fashion (and need) for thick, intense whitening make-up for both sexes. Ironically, the obsession to convey a life of leisure was a near-suicidal endeavour due to the deadly lead-and-arsenic based whitening compounds.

So why flies on the face? The origins of mouche fashion are a bit of a mystery. Some suggest they were adopted to cover pox marks – although to disguise the damage wrought by a smallpox or syphilis attack would’ve required far more than two or three fly-sized patches. For the elite, they ultimately became a means of sending clandestine messages by means of a familiar design and placement code. Think of them like the social media emojis of the day. At high society gatherings, getting noticed was essential and appearance was the be-all and end-all.

This was the era of ‘pride and prejudice’, every detail in a person’s appearance relayed information about one’s status; from the fabric, pattern, line, weave and colour to the cut and curl of their dress said something about them. Outrageously tall, elaborate and powdered wigs, bejewelled shoes and embellished purses signalled your station in the societal hierarchy. The centre-piece of this public broadcast was of course the face, the emotional display screen and communications hub to which all attentions would gravitate. No doubt then, this was the prime spot for adding additional messaging to broadcast your position

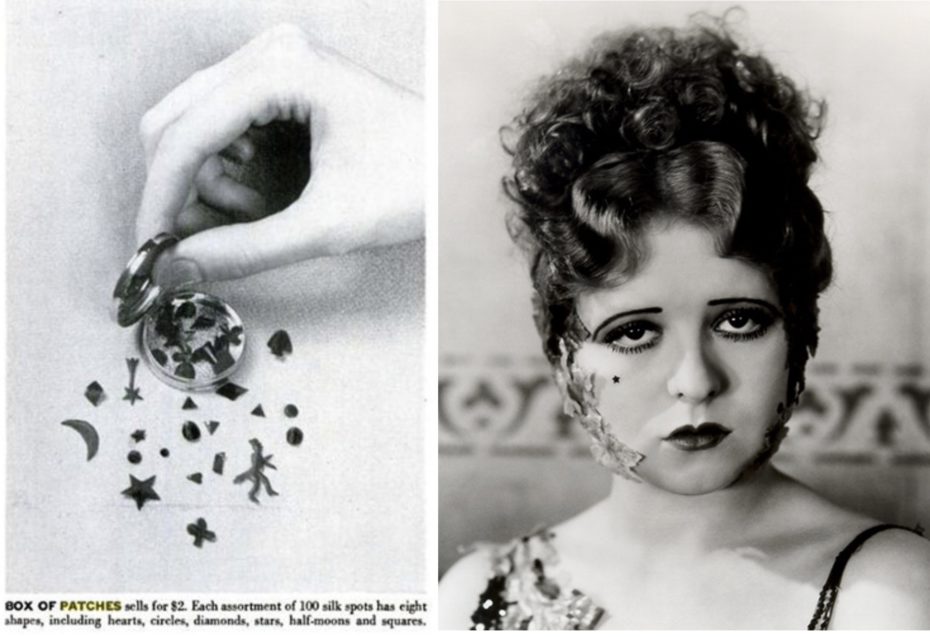

A mouche would have been crafted from satin, velvet, leather and even mouse fur and applied with glue. The shapes were fantastic and infinite: moons, stars, hearts, squares, dots, flowers and ships, even an elaborate horse-drawn carriage had been reported. However, despite these artistic renditions, the placement (rather than the shape of a mouche) was more important and they could be swapped and shuffled around the face as the occasion demanded. Mouches were kept in exotic, petite, finely-crafted and lavishly decorated gold and ivory carriers called boîtes à mouche (‘fly boxes’ in English) and these little boxes were often true works of art in their own right, not unlike a snuff box or cigar case. The production of mouches and their boîtes was a booming industry.

The artistry of placement of mooches and your decision on the quantity required skill and taste: too many looked desperate, too few; passé, and a poor arrangement may have distracted or even compromised one’s natural beauty. A French commentator (anonymous) of the day wrote,

“Women who wanted to create the impression of impishness stuck them near the corner of the mouth; those who wanted to flirt chose the cheek; those in love put a beauty spot beside the eye; a spot on the chin indicated roguishness or playfulness, a patch on the nose cheekiness; the lip was preferred by the coquettish lady, and the forehead was reserved for the proud.”

Not only did the mouches display personal charms and preferences (positioned on the breast, for example, relayed generosity), in Britain one placed on the right-hand side of the face would denote a political affiliation to the Tories whilst a Whig would wear one on the left. In time, their placement became very useful in courtship to convey a lady’s mood or status. An engaged woman wore a heart patch on the left cheek, indicating she was spoken for and once married, wore the patch to the right. One placed by the corner of the eye indicated the wearer was passionate. The position of the mouche was also attributed suggestive names, for example, if she had one placed on the forehead, she was la majesteuse, and la coquette (flirtatious) if worn on the lips. On the nose was l’impudent and if worn on the temple, he or she was deemed l’assassin and considered to be more dignified. La galante placed a patch on the cheek, and la discrete under the lower lip while l’enjouée wore one on the lower cheek fold to indicate playfulness.

Mouches were of course, extremely popular in France, the most powerful, fashionable and extravagant nation of the day. Inevitably, these patches grew physically larger, prompting an 18th century French writer (anonymous) to pen…

“Though I have seen with patience the cap diminishing to the size of patch, I have not with the same unconcern observed the patch enlarging itself to the size of a cap. It is with great sorrow that I already see it in the possession of that beautiful mass of blue which borders upon the eye. Should it increase on the side of that exquisite feature, what an eclipse have we to dread! but surely it is to be hoped the ladies will not give up that place to a plaster, which the brightest jewel in the universe would want lustre to supply … All young ladies, who find it difficult to wean themselves from patches all at once, shall be allowed to wear them in whatever number, size, or figure they please, on such parts of the body as are, or should be, most covered from sight.”

The fashion became so popular and widespread across Europe that some folk wore one or two discreetly whilst some wore so many they appeared to be covered in flies! Henri Mission, another Frenchman, shockingly reported in 1719,

“The Use of Patches is not unknown to the French ladies; but she that wears them must be young and handsome. In England, young, old, handsome, ugly all are bepatch’d until Bed-rid. I have often counted fifteen Patches, or more upon the swarthy wrinkled face of an old Hag threescore and ten, and upwards.”

The fashion for the whitening of the skin continued well into the 19th century, particularly for women. As the trend filtered down through the ranks of society, the skin-whitening agents may have been less toxic, less expensive and less effective, but the disease and violence scars they obscured more abundant. The liberal use of patches by prostitutes, rakes and the like, seems to have turned high society away from the application of mooches, but they stuck to their expensive poisonous skin whitening potions and treatments. Face whitening requiring the use of lead and arsenic compounds finally fell away in the later 19th century when the toxic effects of these poisoning compounds started to be understood.

Despite being all the rage for almost two centuries, the mouche made little or no appearance in the grand aristocratic portraits of the 18th century. It wasn’t until “It Girl” Clara Bow was famously photographed with a star on her cheek that mouches returned as a fleeting fad in the 1920s, and again in the 1940s and 1950s when Marilyn Monroe and her natural beauty spot took Hollywood by storm. Then there was Cindy Crawford’s beauty spot in the 90s of course, but in the 2020’s we appeared to have come full circle with cute emoji-style pimple patches to not only hide blemishes, but treat them Salicylic Acid to help break up congestion in pores.

We love a 400 year-old fashion comeback.