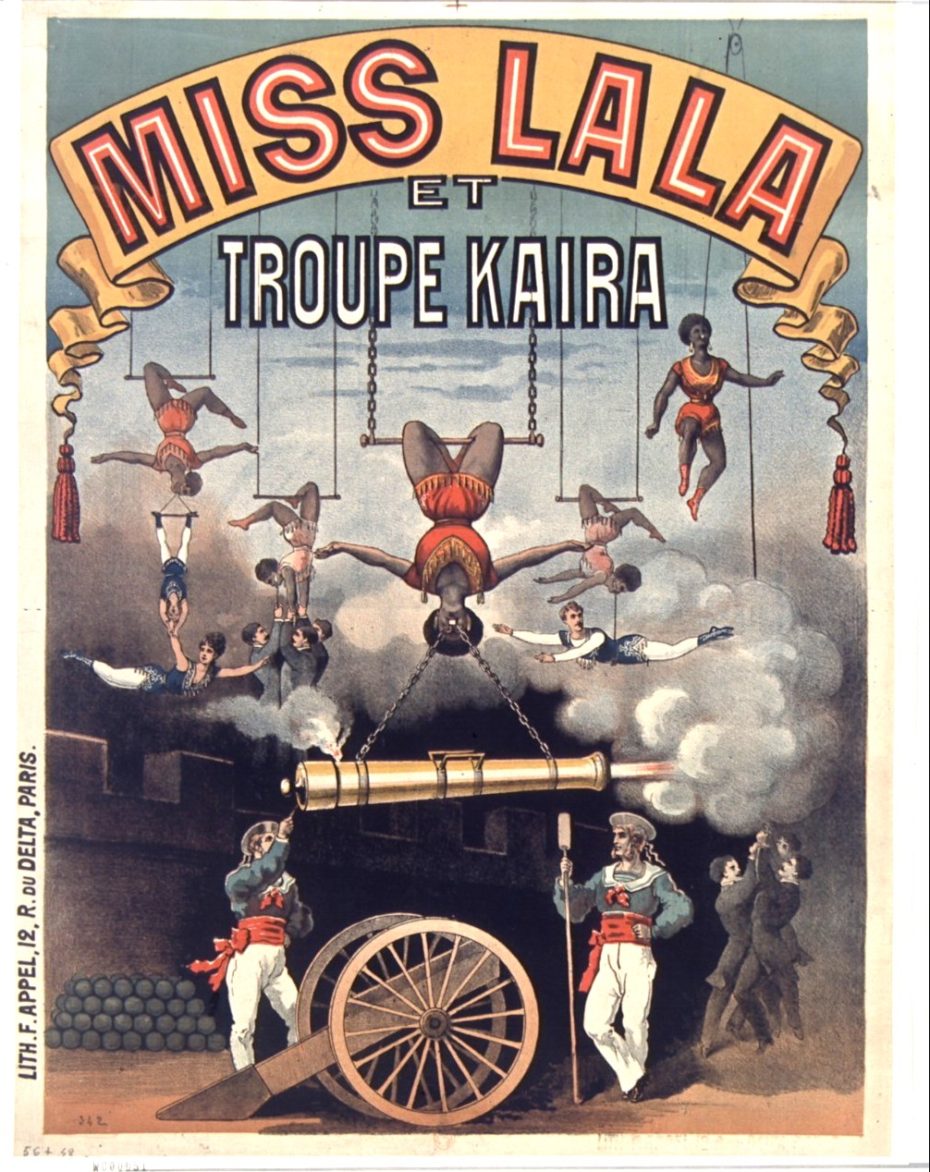

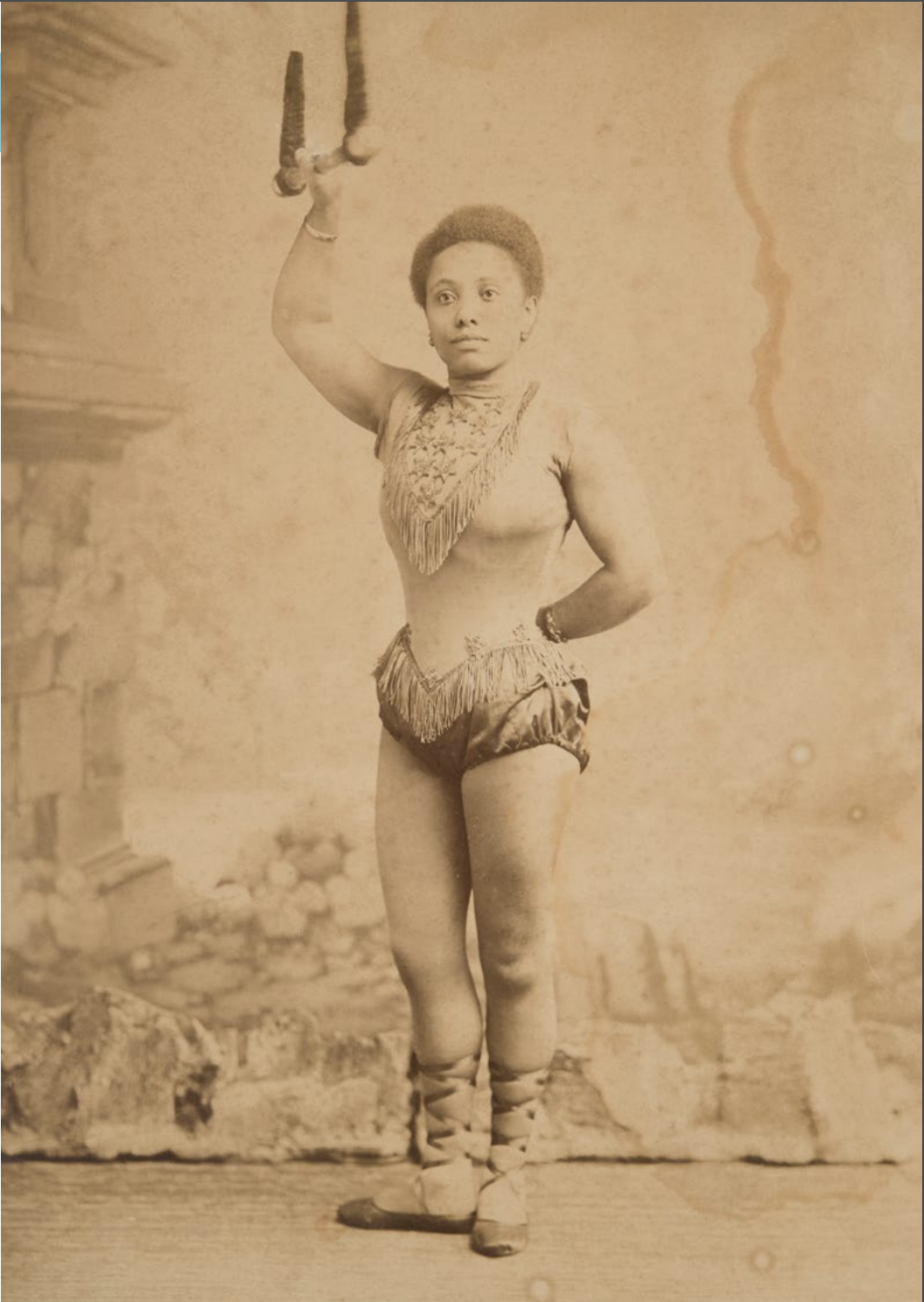

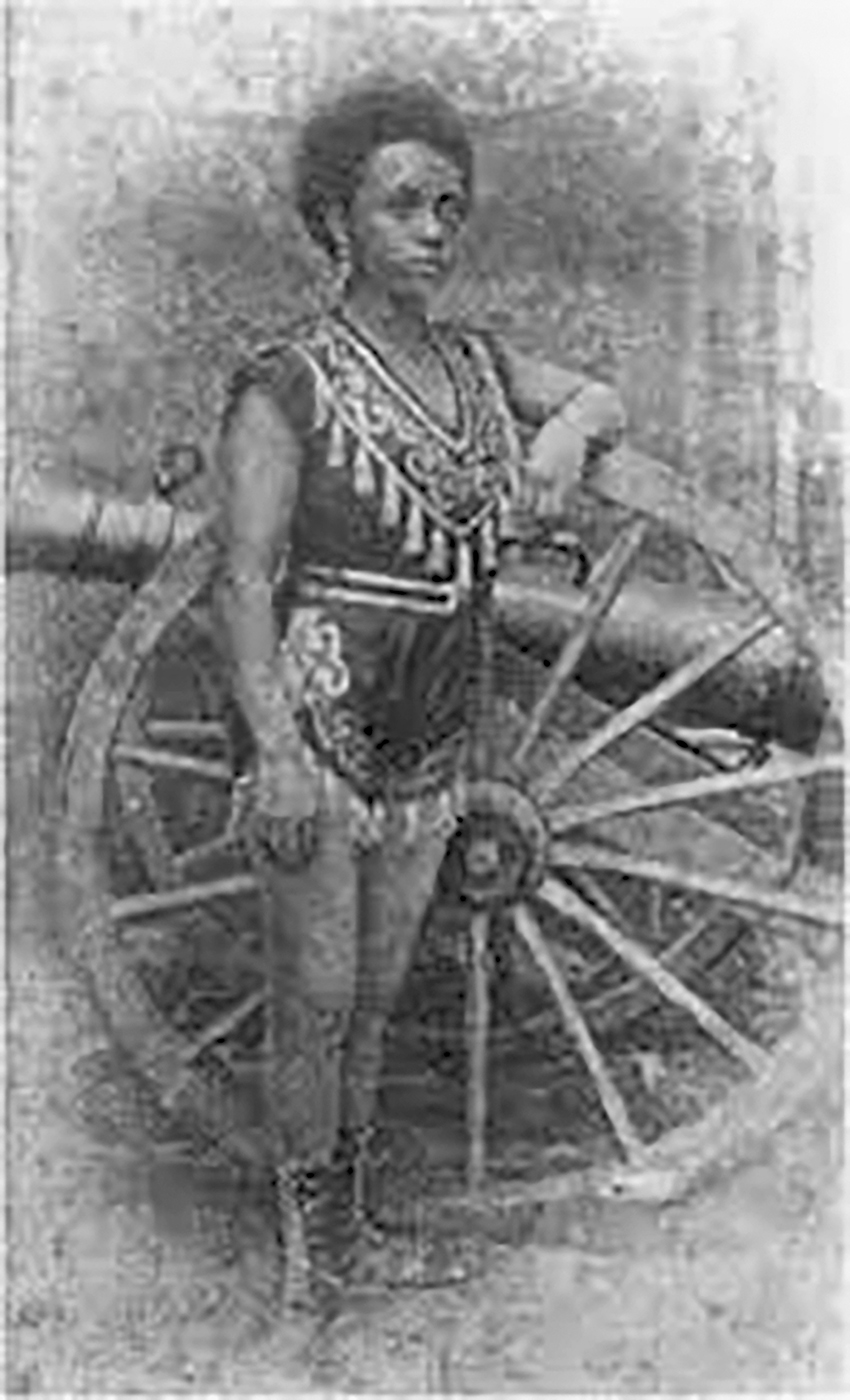

A diminutive Black woman hung upside down from a trapeze as two men pushed and shoved a 200 pound cannon to the center of the circus ring. She grasped a chain on the cannon and hung it on a hook held between her teeth. At a signal, she was hoisted aloft. The audience watched with bated breath as the chain on the cannon tightened. Inch by inch the cannon was hauled up from its wheeled mount, until it was dangling from the woman’s mouth like a colossal pendant, two metres above the ground. The two men crouched down and with a warning shout, one of them pulled the lanyard on the cannon. It exploded with an enormous blast that caused the crowd to jump in their seats. When the smoke cleared, Miss Lala was swinging wildly from the massive recoil, the cannon still tenaciously gripped between her jaws of steel.

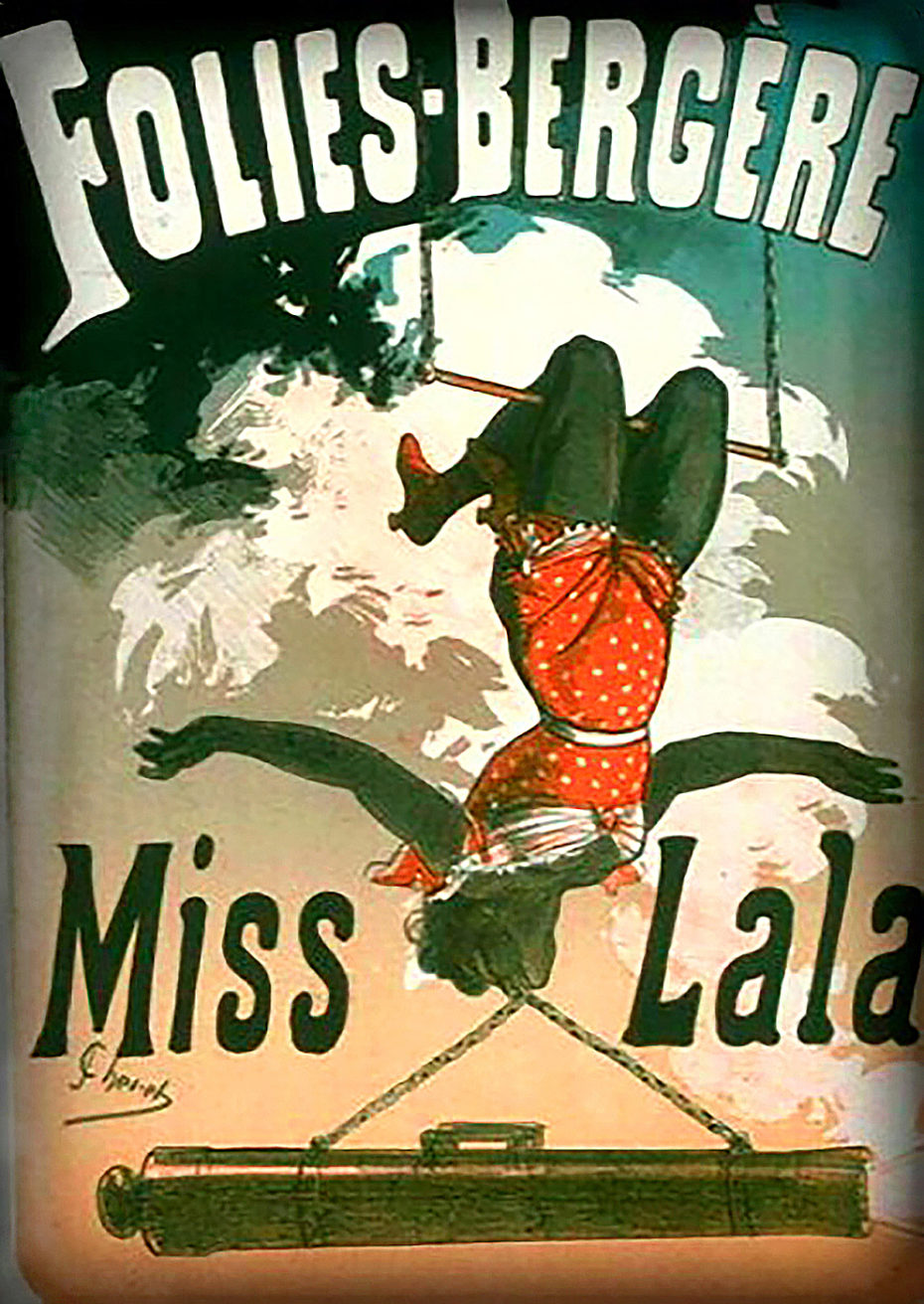

Gilded Age Paris had never seen anything like Miss Lala. There were plenty of graceful aerialists and muscular men performing prodigious feats of strength, but here was a small Black woman carrying a massive cannon between her teeth. Miss Lala was the sensation of Paris during her troupe’s month-long engagement at the Cirque Fernando from December 1878 to January 1879.

One of her fans was Edgar Degas, who spent several evenings that January peering through binoculars trying to sketch the swaying figure above him. He created numerous drawings of her ascending to the top of the building gripping a swivel between her teeth. These studies formed the basis of his most unusual work, Miss Lala at the Cirque Fernando, which debuted at the Fourth Impressionist Exhibition in Paris that year.

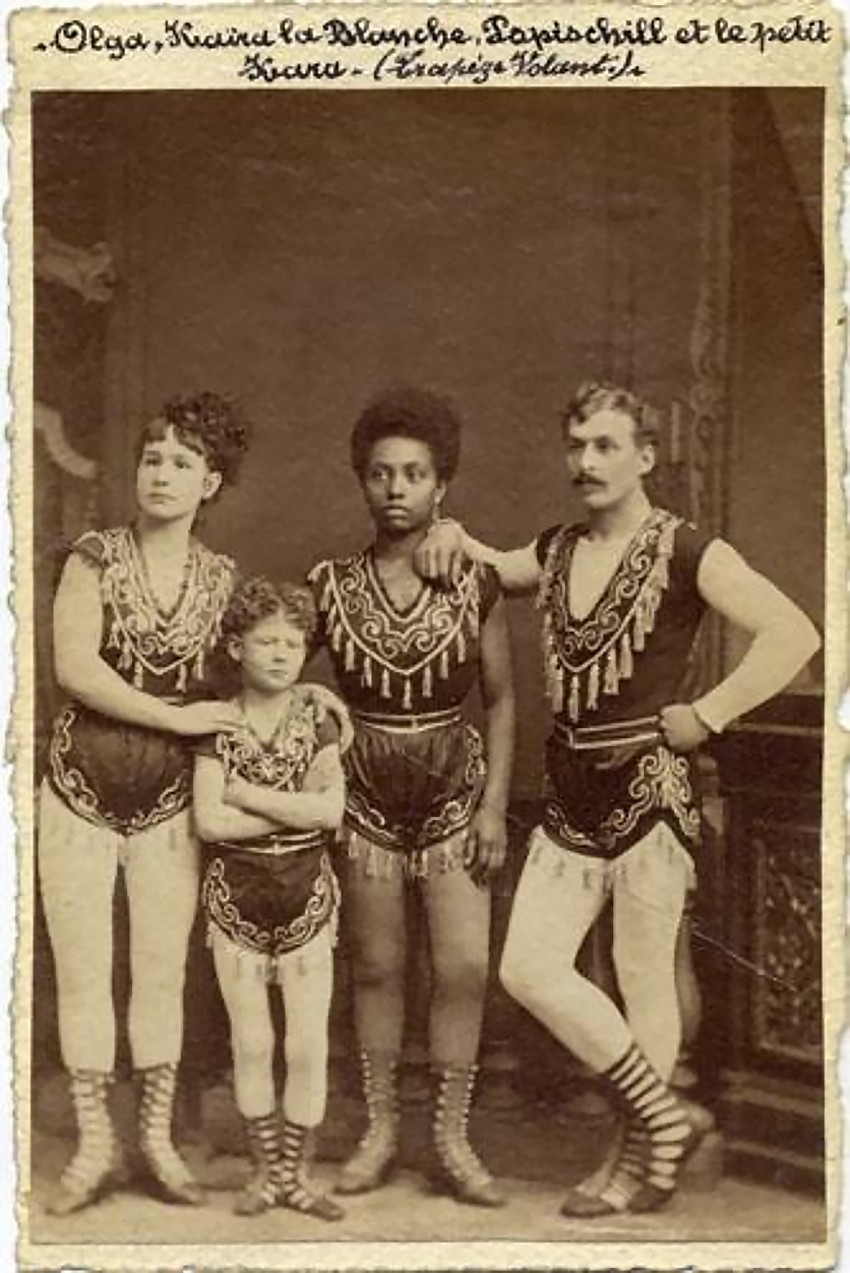

After that month in Paris, Miss Lala and Troupe Kaira left for London, where newspaper articles continued to marvel at her act. She was called the Black Venus, La Mulâtresse-Canon, Venus of the Tropics, the Black Pearl. All kinds of exotic stories circulated about her. A London newspaper claimed that she was an African princess who was sold into slavery and ended up in France.

It was not until 1911 that the public learned that Miss Lala was not from Africa or anywhere tropical at all. That year, early fitness trainer Edmond Desbonnet published Rois de la Force (Kings of Strength), a colorful history of the strongmen and strongwomen of his time. Desbonnet interviewed Miss Lala for a lengthy passage in the book, including a profile of her professional accomplishments and a biography. He also confessed to being jealous of her biceps, which he measured at 15 1/8 inches (38.5 centimeters).

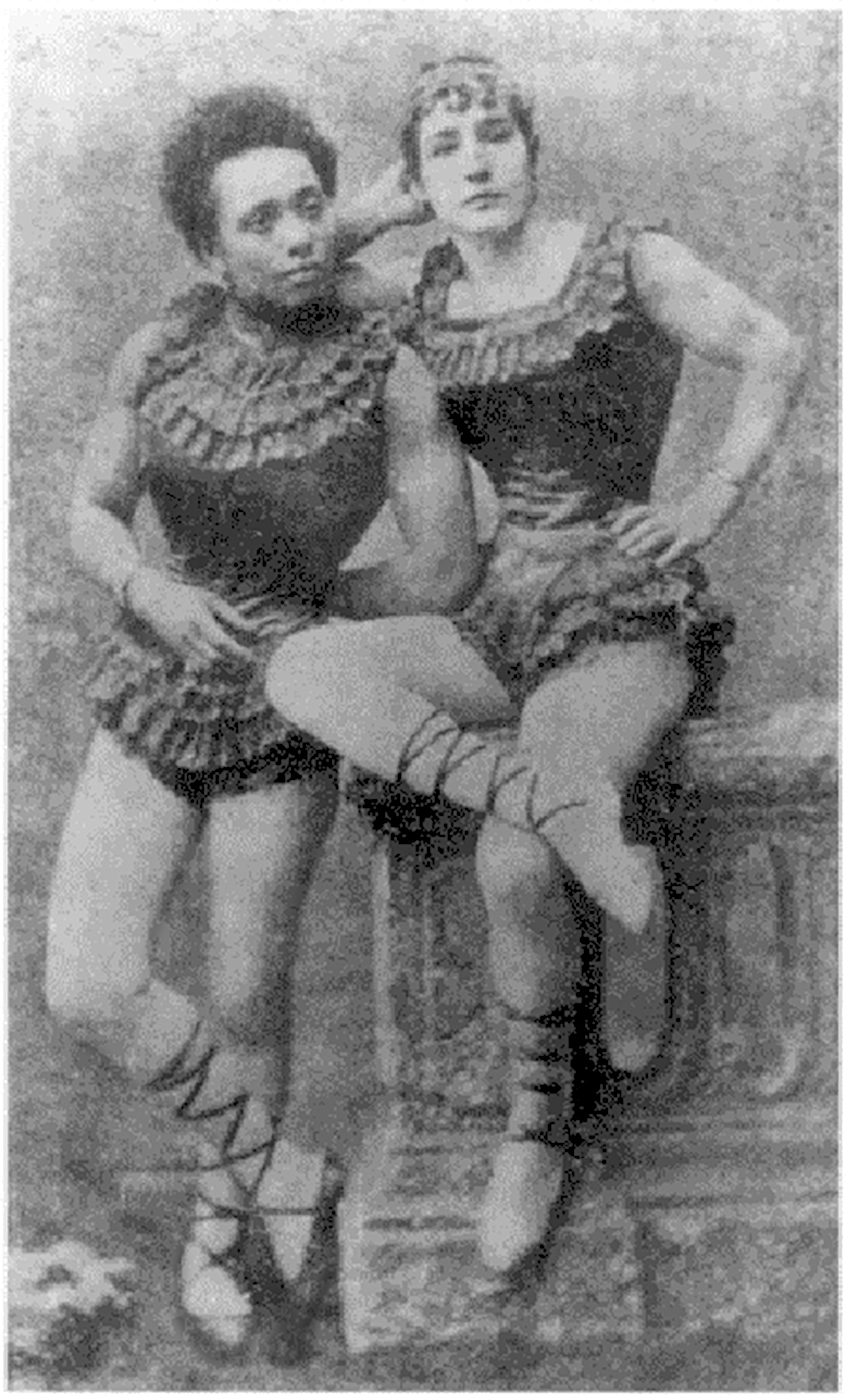

According to Desbonnet, Miss Lala was born Anna Albertine Olga Brown on April 21, 1858, in Prussia. Her father, Wilhelm Brown, was a Black German, and her mother, Marie Christine Borchardt, was a white Prussian. She began performing at the age of nine and became proficient in the high wire, the flying trapeze, and the iron jaw act.

While the high wire or tightrope dates to Ancient Greece, the flying trapeze and the iron jaw act were both quite new when Miss Lala was performing. In 1859, astonished audiences at the Cirque Napoleon in Paris first witnessed Jules Leotard’s flying trapeze act, a 12-minute routine in which he leapt from trapeze to another and did a somersault in mid-air. Leotard is also the inventor of the form-fitting one-piece garment that bears his name. The iron jaw was developed not long after as an innovation to the flying trapeze.

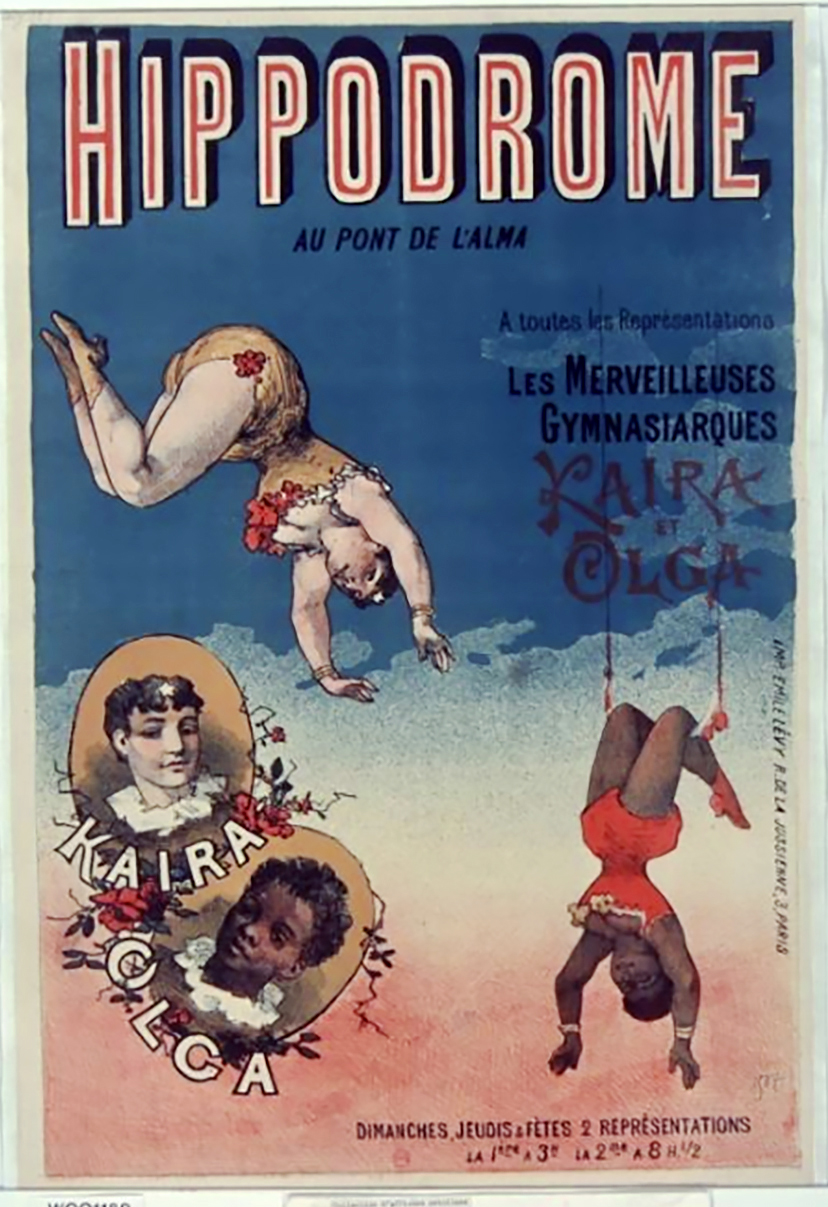

After wowing London in the spring of 1879, Miss Lala and Troupe Kaira returned to Paris to open the new season for Cirque Fernando. Le Figaro reported that Miss Lala’s trapeze partner, Kaira Blanche, was injured in a fall. Nevertheless, they continued performing at the Follies Bergère and the Hippodrome Au Pont De L’Alma.

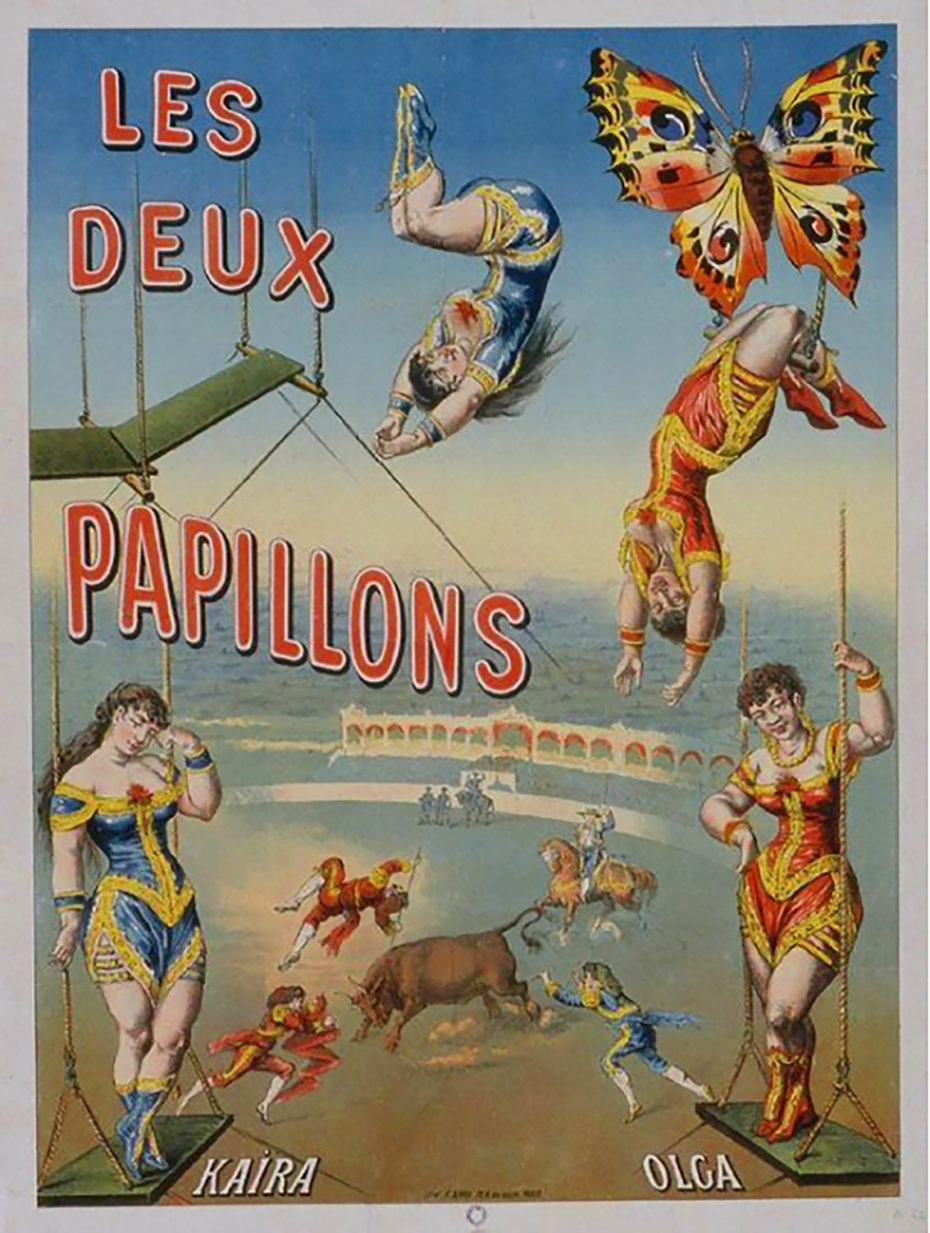

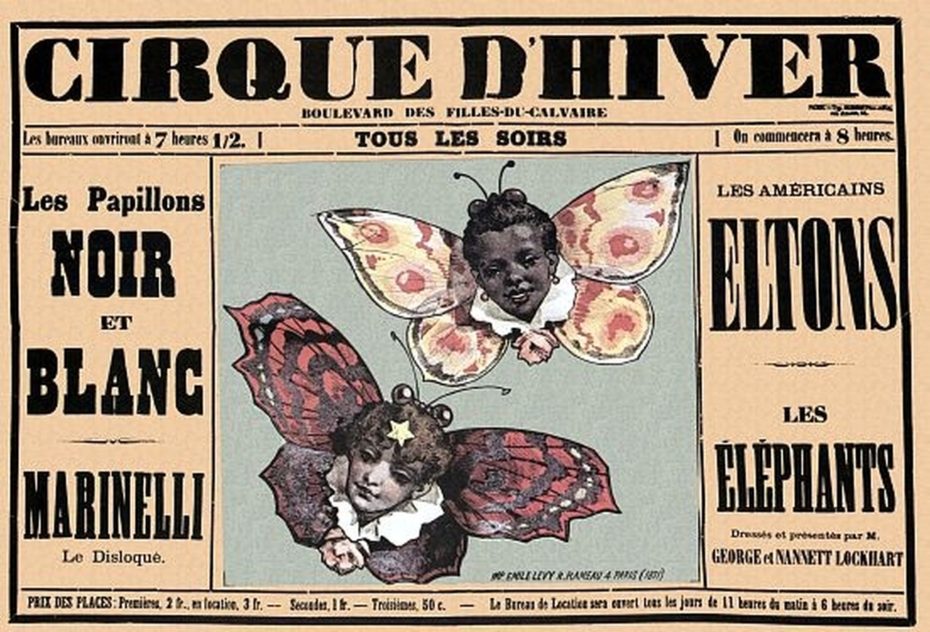

Miss Lala retired the cannon act in the early 1880s and from then on called herself Olga. She and Kaira Blanche split from the troupe and formed their own flying trapeze act. Now billed as the “Black and White Butterflies – Olga and Kaira,” they dazzled France and Spain before arriving in London, where their appearance at the Royal Aquarium excited a flurry of newspaper reports.

Returning to Paris in August 1884 for an engagement at the Cirque d’Ete, they were described as “exceeding in daring anything accomplished by the renowned Leotard.” Tragically, in 1888, after performing their flying trapeze act for more than five years, Kaira fell to her death.

Olga seems to have found comfort in the arms of a handsome Black American contortionist, Emmanuel Woodman. They were married in October that year. In the 1890s, Olga created a ladder acrobatics act with two new partners. Calling themselves the Three Keziahs, they performed internationally with Olga’s husband, traveling as far as Sydney and New Zealand.

Woodman got a job managing the luxurious Palais d’Eté in Brussels and they settled there in the early 1900s. By then, he and Olga had three daughters. The Palais d’Eté was part of the Centrale Halles, an opulent market in the old fishing port comprised of two pavilions. One of the pavilions was dedicated solely to entertainment in 1893, with an ice skating rink in the winter called the North Pole and a grand theatre in the summer called the Palais d’Eté. Mata Hari performed at the Palais d’Eté in 1912 and during World War I, the hall was taken over by the Germans.

Woodman died in 1915 and four years later, Olga applied for a visa to the United States to visit his family in St. Louis, Missouri. Here the trail runs cold. It’s not known if the visa was granted or what happened to Olga after 1919.

The story of Olga and her husband provides an alternative to the narratives we more often hear about Black people in the late 1800s. In an era where it was not uncommon to see Africans displayed in dime museums, Olga was hailed as a performer with exceptional ability and imagination. The painting of her by Degas can be seen at the National Gallery in London, a free Black woman who created her own life and legend, soaring up the heavens with her iron jaw.

About the Contributor