Throughout the latter half of the twentieth century and well into the beginning of the next, it’s easy to track our fascination with young women attempting to figure out life – they are witty, tenacious, and often keenly perceptive of the world in which they exist and their place within it. Their names have become household, pop-culture gospel: Holly, Carrie, and now (for better or worse) Emily. But there is one name on that list that often fails to come up: Sally Jay Gorce.

Now, let’s go back for a moment. In November of 1958, Esquire magazine began serialising a novella that told the story of a young woman living in New York. She was a bit of a party girl, and she was looking for a rich man to make all her dreams come true. What those dreams were, exactly, no-one was really sure. Its author, Truman Capote, had originally sent the story to Harper’s Bazaar, who later backed out on the basis that it was just a bit too risque. As well as being serialised in Esquire, the novella was published in full by Random House. It was called Breakfast at Tiffany’s. By 1961, it had been adapted for the screen into what would become one of the all time greats, Audrey Hepburn stepping into the OG little black dress in a performance that would both irk (one person, Capote, who wanted Marilyn Monroe) and bewitch (everyone else, who, as the saying goes, either wanted to be her or be with her.)

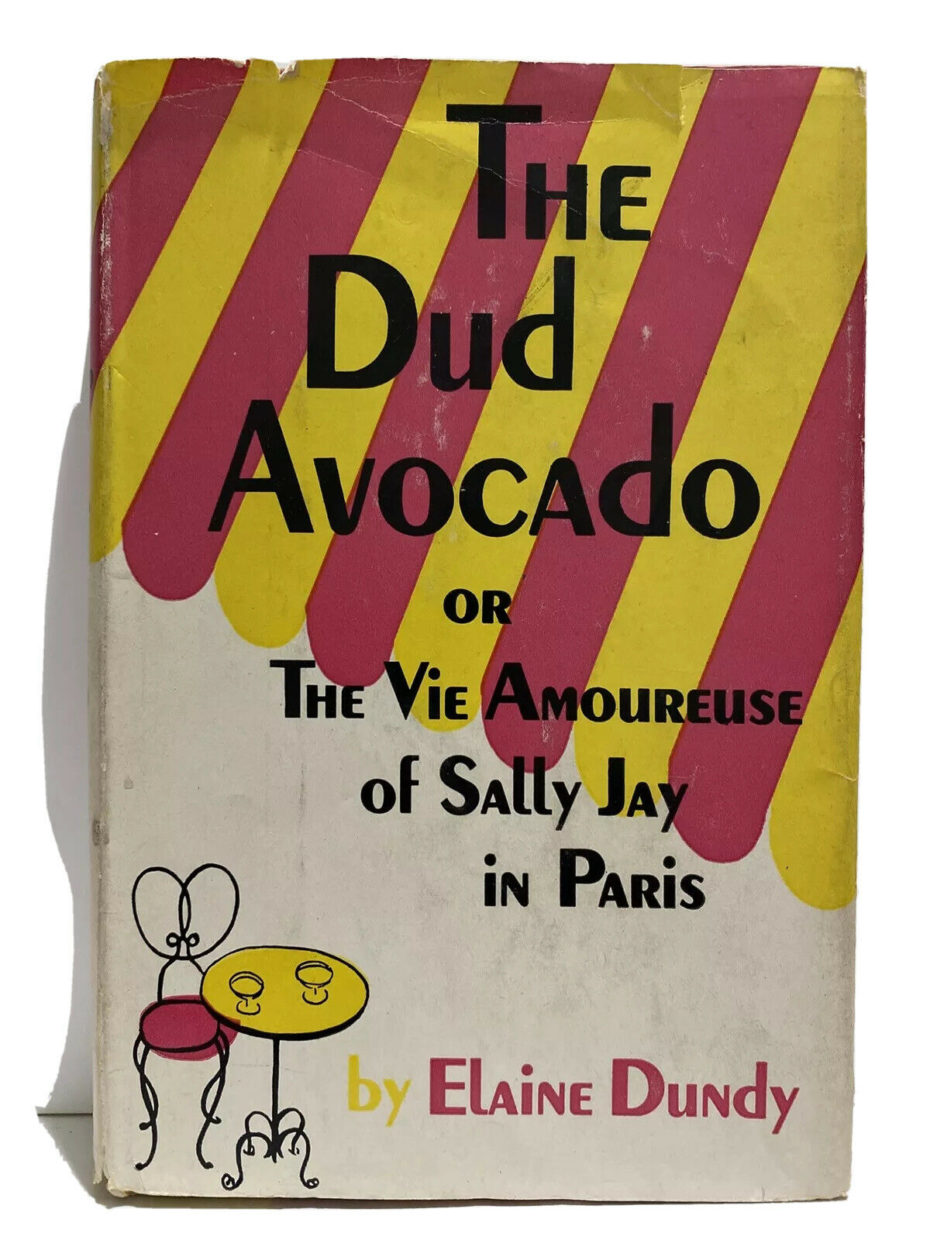

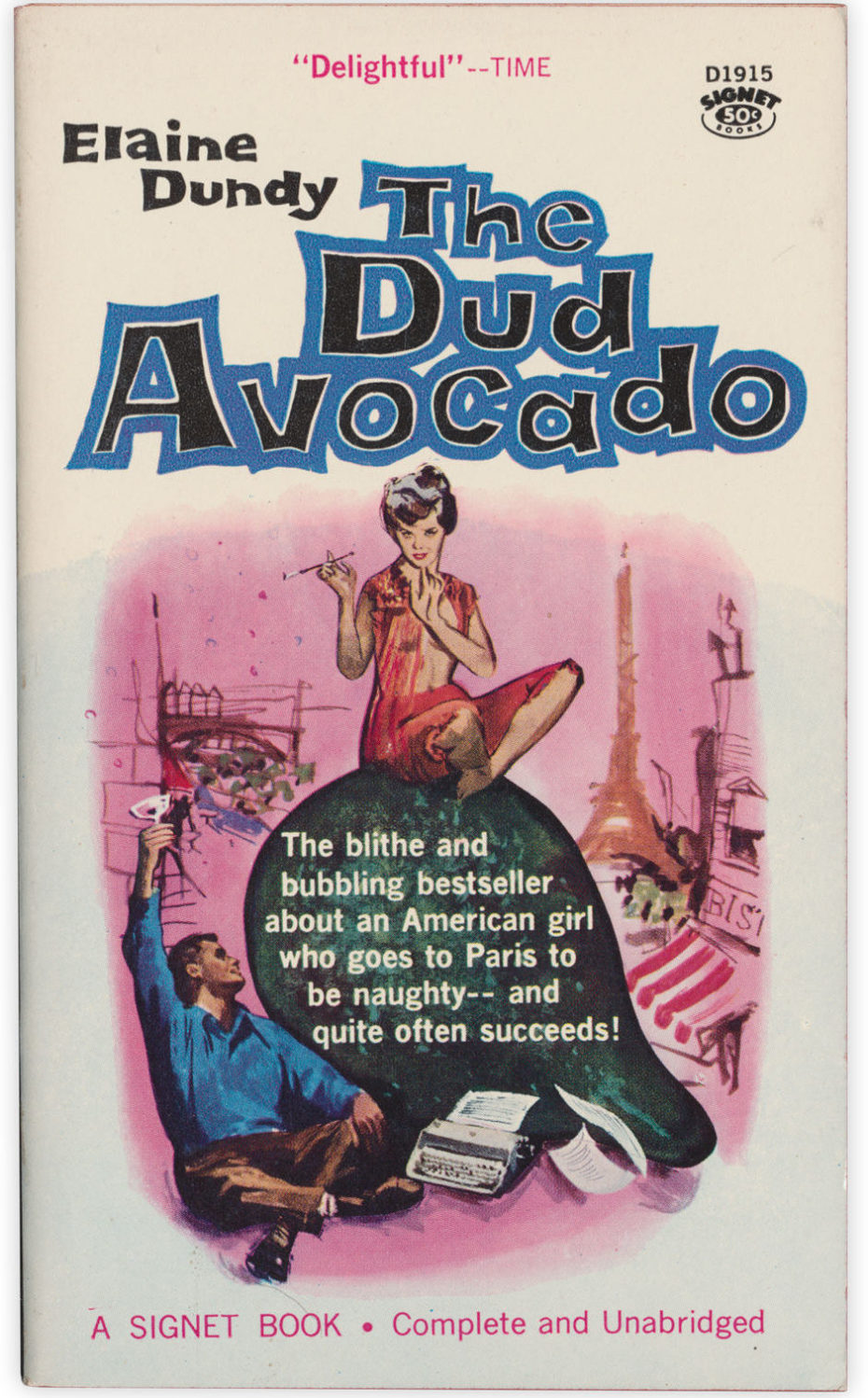

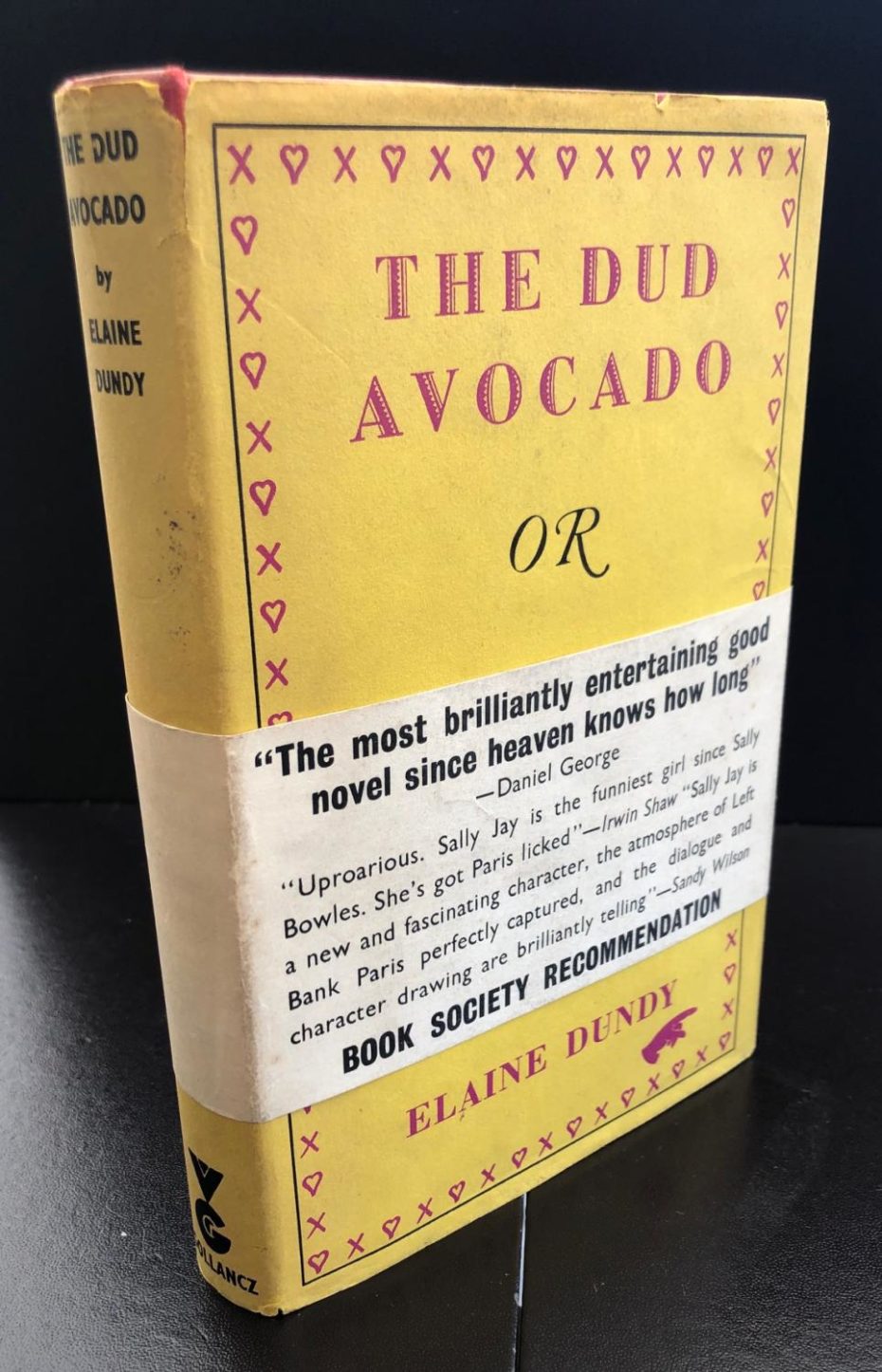

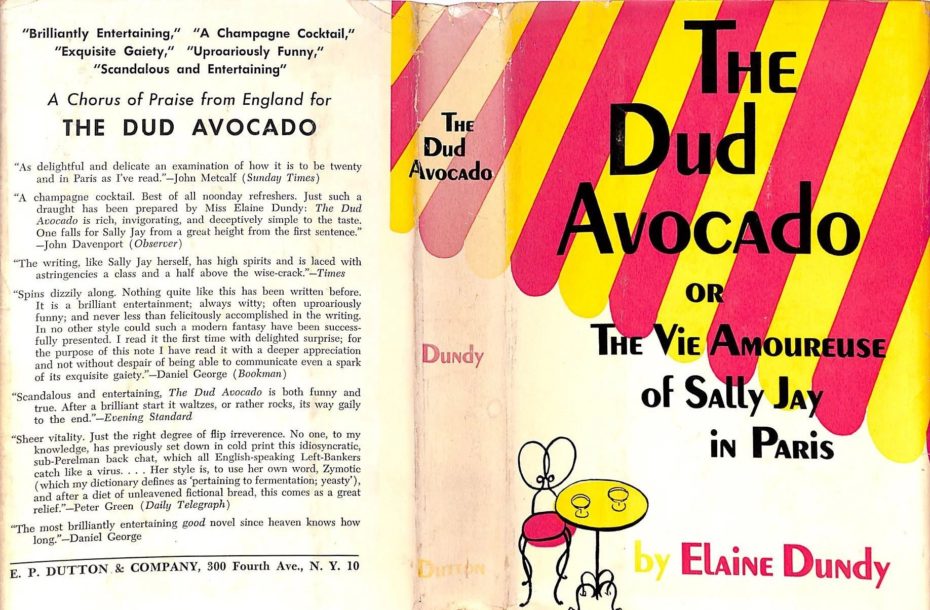

But also in 1958, some nine months before Breakfast at Tiffany’s was published, there was another novel making the rounds, already on its way to becoming a cult favourite. In January of that year, the writer Elaine Dundy – previously an actress in Paris and London, now married to the theatre critic Kenneth Tynan and a new mother – had released her first novel into the world. She called it, rather coyly, The Dud Avocado.

The Dud Avocado tells the story of Sally Jay Gorce, a young woman, so she says, “hellbent for living.” It’s the fifties, and Sally – Gorce to those who know her – is in Paris. An American and sometimes actress living off of the benevolence of star-gazing old Uncle Roger back in the States, whose only stipulation is that when she comes back she tells him all about it (the dream!), Gorce spends her days stalking the Left Bank, looking for adventure, fame, and – well, aren’t we all, when in Paris – love. And if she can’t find love, she’ll take a rendez-vous at the Ritz with an Italian diplomat who always shows up late (it’s tough, after all, balancing a wife, a mistress and another mistress) and leaves her waiting at the bar, knocking back “sazaracs and slings and heaven knows what else”.

It’s all par for the course for Gorce, though, when Larry, a boy from back home whom she bumps into in Paris, scolds her for all her ‘drifting’ and for wasting her time ‘bumming around with a tourist-trap Casanova’, she says, warily, “Well, but living you know…”

Unbeknownst to Larry, all this drifting is not wasted time. Gorce is a woman with a plan, and that plan is to sharpen her wits: “It takes a lot of training. You have to start very young. I want them to be so sharp that I’m always able to guess right.” She hates when people refer to her as a child, and when they do she has a desperate desire to blurt out the most lurid thing she can think of. She is a young woman in search of what it means to be a woman, to be seen as a woman. It’s a familiar tale, often told in a familiar locale; in Paris, anything can happen, in Paris, you’re always the main character. And boy, is Gorce a loveable one. She shares a lot of things with her contemporary. Like Holly Golightly, who has her mean “reds”, very different, she’s keen to point out, from the usual blues, Gorce has her midnight-black moods; excited and deeply dreading, and her midnight-blue ones; calm but deeply excited. Like Holly, she has an almost disinterest in her own body when it comes to sex and men. And like Holly, despite her attempts to adopt a new demeanour, the old her continues to slip out. But she also, happily, differs from Holly. Her story is not quite so bleak, not so midnight-black. There is a lightness to The Dud Avocado, a champagne fizziness that leaves you giddy.

Elaine Dundy based the novel on her own exploits when she lived in Paris for a year before heading to London to act. “All the outrageous things my heroine does, “ Dundy has stated in interviews, “like wearing an evening dress in the middle of the day, are autobiographical. All the sensible things she does are not.” Groucho Marx, who loved the book, sent her a note: “If this was actually your life, I don’t see how the hell you ever got through it.” And as Gorce’s life mirrored Dundy’s, in some ways so did Dundy’s mirror Gorce’s. Once she arrived in London, there was a whirlwind romance with Kenneth Tynan who reportedly told her on their first date: “I am the illegitimate son of the late Sir Peter Peacock. I have an annual income, I’m 23, and will either die or kill myself when I reach 30 because by then I will have said everything I have to say. Will you marry me?” She said no, and then she said yes. The telegram to her family read: “Have married Englishman. Letter follows.”

But their marriage proved to be an unhappy one, with Tynan eventually confessing to her some years in that he wished to return to his ‘Oxford practices’, which involved books on sado-masochism and a schoolmaster’s cane. Yikes. It continued to deteriorate, and appeals by Tynan to their mutual friend Gore Vidal for help yielded only one comment: “Elaine wants something that neither you nor anybody can give her. She wants herself.”

Dundy’s method of using her own life as a springboard is similar to that of another woman several decades later, who in November of 1994 began writing a column for the New York Observer detailing the exploits of her and friends as young women making a life – “Well, but living you know…” – in the Big Apple. She called the column Sex and the City. Written in the first-person, Candace Bushnell detailed her real experiences, with the inaugural edition recounting the story of her visit to La Trapeze, a swingers club: “When the eggheads at the University of Chicago released their 750-page sex survey in October, with its finding that Americans are happy to do it with the same person in the same position for years and years, New Yorkers took one look at the newspaper and said, “I don’t think so.””

Later on, Bushnell would switch to an alter ego – you guessed it, Carrie – so her parents wouldn’t connect the sex scenes with herself. In 1998 it was adapted by HBO into a show of the same title, followed by two feature films and now, in 2022, the widely discoursed spin-off, And Just Like That… Like Holly before her, Carrie is also a bit of a party girl, who likes nice clothes and rich men – this time the rich men are not necessarily the means by which her dreams come true, but they are a nice addition. Theirs is a story still being told over and over, and we are still fascinated by it.

Gorce might be doing it across a big pond, and then a smaller pond, but her story is the same, and nothing is more perennial than the story of the questing American woman in Paris. Its most recent interprétation can be seen in a Netflix offering – this time the girl is from Chicago, she less seeks out rich men than is sought out by them, but she really likes nice clothes and has big dreams of her own. Her name is Emily and she’s just been transferred to Paris. Hugely popular on its release – which may be in part due to its timing, smack-bang in the heart of a pandemic when those outside of the City of Light had probably never felt so far from it. Emily in Paris also attracted a large wave of criticism. Emily is a new, younger version of Carrie, tapped into our Instagrammable present. And the show’s aesthetic neatly follows the rhythms of the algorithm, favouring scenarios and visuals that have no basis in reality – Emily’s only problem when it comes to locating her new living arrangements in Paris, a rather lovely Haussmannian abode that is slightly too big to be a real chambre de bonne, is that she gets the flooring numbers mixed up by following American conventions and not European ones. Quelle horreur! There are endless selfies with croissants as if to shout: I am here! This is Paris! And this is the plight of the city, to be endlessly buried under our imagined ideas of it.

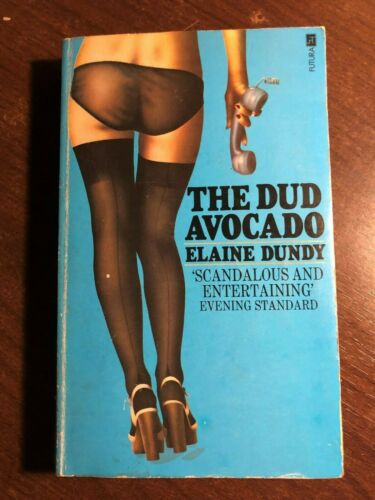

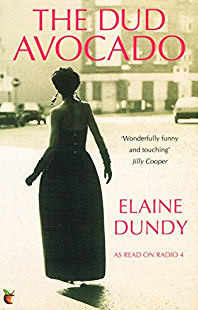

So if the questing woman who comes to Paris for answers has always been an audience favourite, why is it that Sally Jay Gorce, arguably the most funny and loveable of the lot, has slipped off the radar? The Dud Avocado has been in and out of print since its publication. Virago released a new edition with a cover redolent of the opening scene of Breakfast at Tiffany’s in 1993. This was followed by NYRB’s edition in 2007. Most recently, in 2018, it was included in Virago Modern Classics’ 40th anniversary collection with a trippy new cover bedecked in a Martini motif. Despite being instantly popular on release in 1958, with the film rights snapped up, it never made it to the big screen, and has never done so since. Perhaps this is where Gorce’s injustice lies, for whilst Audrey Hepburn’s Holly has long been cemented as one of the all time great performances, Truman Capote’s Holly, and the novella from which she hails, has remained somewhat in its shadow. And, unlike Holly, Carrie, and now Emily, Gorce never did get the screen treatment and, as a result, never quite dug into the public’s cultural consciousness. This is a shame, for while Gorce comes on the back of figures like Henry James’ Daisy Miller, is Holly’s contemporary, and the predecessor for Carrie and Emily, of all these women, which one would you most want to be friends with? As journalist Rachel Cooke says in the introduction to the 2018 edition, “Gorce, of course!”

Pick yourself up a vintage copy on Ebay.

By Freya Bainbridge