French fashion designers have long been at the forefront of avant-garde style and Paris has long been considered the birth city of fashion – the ultimate fountain of sophistication, glamorous muses and endless inspiration. But let’s turn back the clocks and leave the capital for the villages of provincial France where a part of French fashion history has been largely overlooked. From giant bows to statement hats to elaborate lace and embroidery, it’s high time that France’s many folk traditions get the nod they deserve from the world of haute couture – n’est ce pas?!

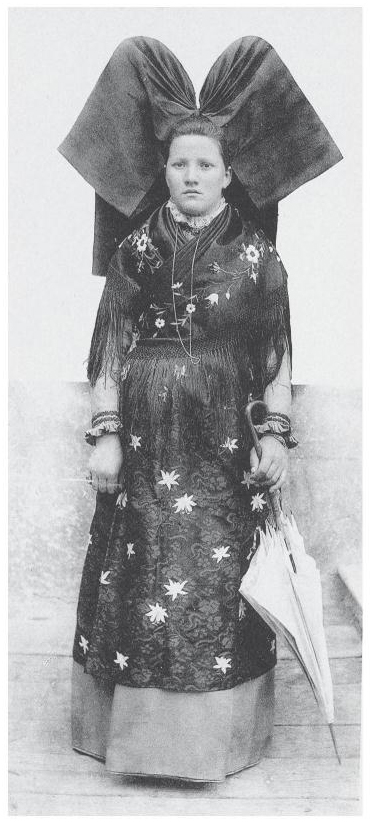

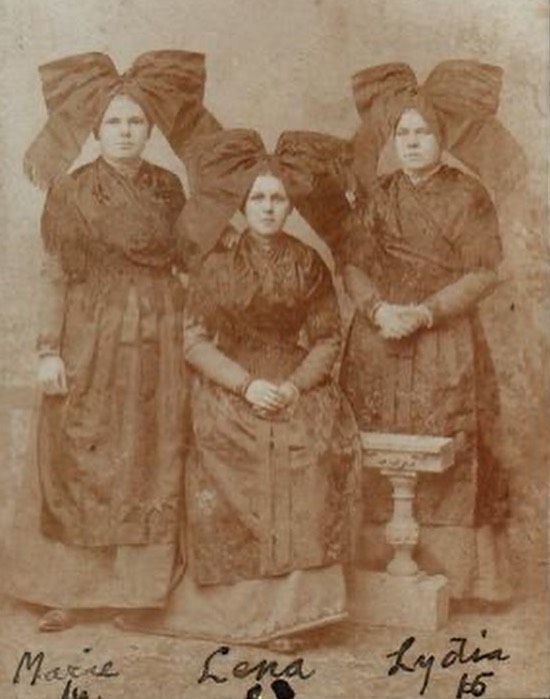

First we head East to Alsace-Lorraine where the schlupfkapp, or “the bow cap,” was popular in the early 19th century. Fashion publications have long lamented the rise and fall of “the big bow.” Noting the bow’s presence on the Spring 2022 runway shows (from Moschinto to Batsheva to Comme des Garçons), Kristen Bateman wrote in Harper’s Bazaar that “perhaps no other motif in fashion is as divisive as the bow. Some bows suggest saccharine girlishness, some prim prep style, but regardless of the implications, the bow is a silhouette that carries reams of symbolism and always inspires a strong reaction.” The traditional bows of Alsace actually began at a much more modest size, with a bow of just a few centimetres wide tied with a ribbon. Technical advances led to bigger and bigger bows, eventually reaching 35 centimeters.

Religion divided schlupfkapp wearers. Both Catholic and Protestant women — married and unmarried — adopted the style, but the Protestants were more reserved, with a somber black bow that fell to the shoulders. Catholics, on the other hand, had more liberty in terms of color, fabric and embroidery, often wearing bows that went down to the waist.

Given Alsace-Lorraine’s complicated history (changing hands between France and Germany before finally reuniting with France after the Second World War), the region’s heritage, especially expressed through fashion, has always been political. In 1793, Jacobin leader Saint-Just banned the coiffe à bec, a traditional cap, because it was considered “too German” during the era of national reunification following the French revolution. After its disappearance sometime around World War II, the bow saw an unlikely renaissance as a symbol of identity in 2014, during the proposed fusion of the Lorraine and Champagne-Ardennes regions. Those supporting the “Unified Alsaciennes” protested against the breaking apart of historic Alsace by proudly wearing schlupfkapp.

Until the late 1920s when a new era of fashion consumption was born, just south of Alsace, one would find the local folk in la mode Bressane. Of very ancient origin, the “chimney” hat is the centrepiece of the costumes of the Bressane…

Ladies were expected to conceal most of the hair under the impressive headdresses which served as an indicator of status and age, depending how the woman styled it.

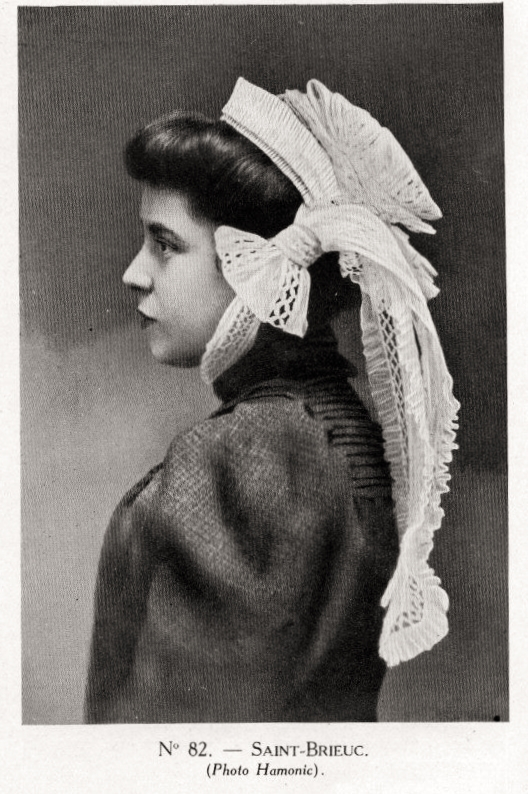

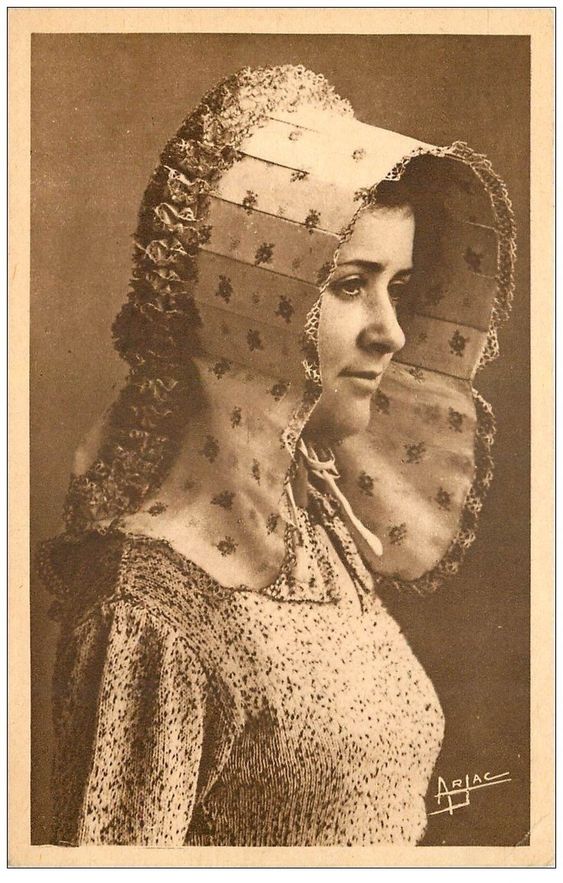

Let’s now head in the opposite direction to the Atlantic coast of France, where a different sort of headwear became popular in the 19th century: the Bigouden headdress…

Like the schlupfkapp, it had modest origins, descending from the religiously-inspired headgear of the Middle Ages. Over a bun, Breton women known as the bigoudènes would wear a basic black bonnet, covered with a red band. This Bigouden headdress continued to get taller and by the 20th century, had also changed design: the color changed to white, decorated with fine embroidery (normally in flower patterns) that took the place of the ribbons. And it continued to grow — from 5 centimeters to 10 to 20 and finally 30 centimeters by the 1960s. The headpiece became symbolic of a region with a unique cultural heritage, with the area even becoming known as Bigouden, thanks to the recognisable coiffe. Famed painter Paul Gauguin included the hat in his paintings of bigoudènes. The headwear even inspired the Bigoudène briochée pastry, which comes in both sweet and savory varieties.

The unique style fell out of popularity by the second half of the 20th century. Some of the reason might be practicality. It took upwards of 30 minutes to put on the hat, with the use of many pins to make sure it would stay upright all day. Still, in 1977, some 31% of Breton women over 46 years old regularly wore Bigoudens, but by the early 1990s, there were only around 500 bigoudènes continuing the tradition. From the 1990s, the French food company Tipiak invited them into French living rooms across the country when they featured some of the last bigoudènes in their TV advertising campaigns, including Maria Lambour. She continued to be featured in the ads until died in 2011. Another locally famous bigoudène, Marie Pochat, told a television host in 2016 that she began wearing the headdress at 12 years old: “Without this headdress, I feel that I miss something”. She died at the age of 102 in 2018.

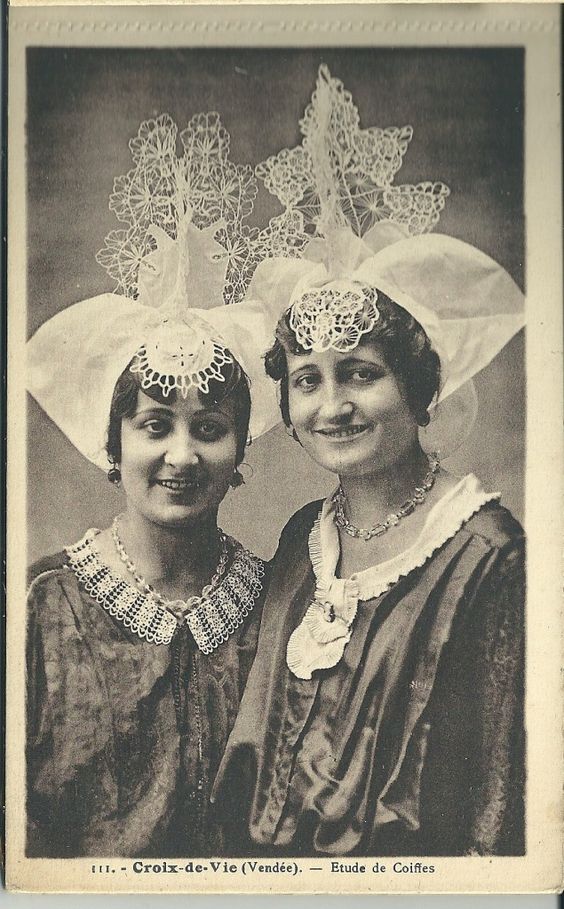

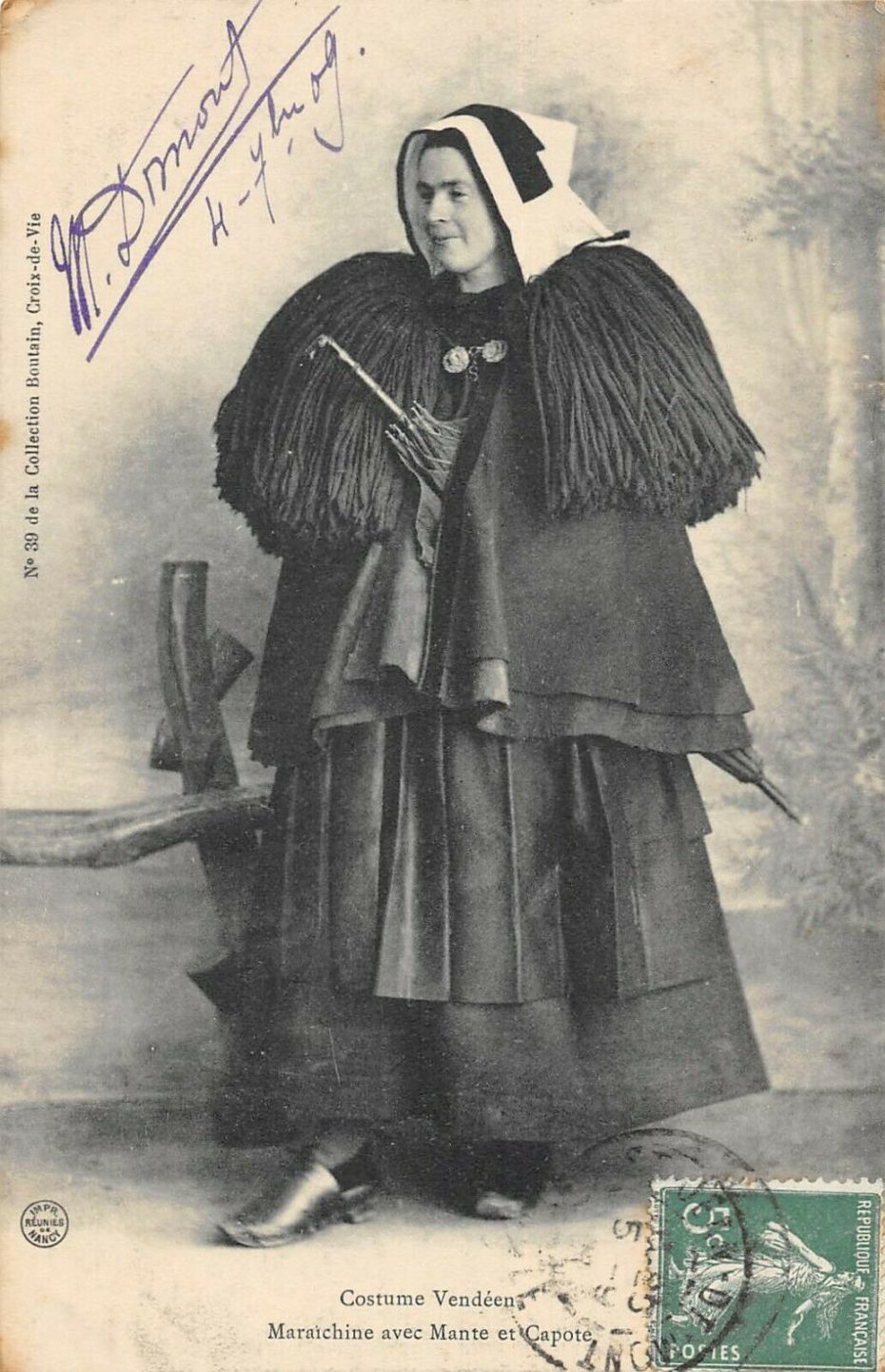

Headdresses across Brittany differed depending on which parish you were in – seemingly competing with neighbouring territories by creating more and more outlandish style. Some designs look straight out of the future or a sci-fi film….

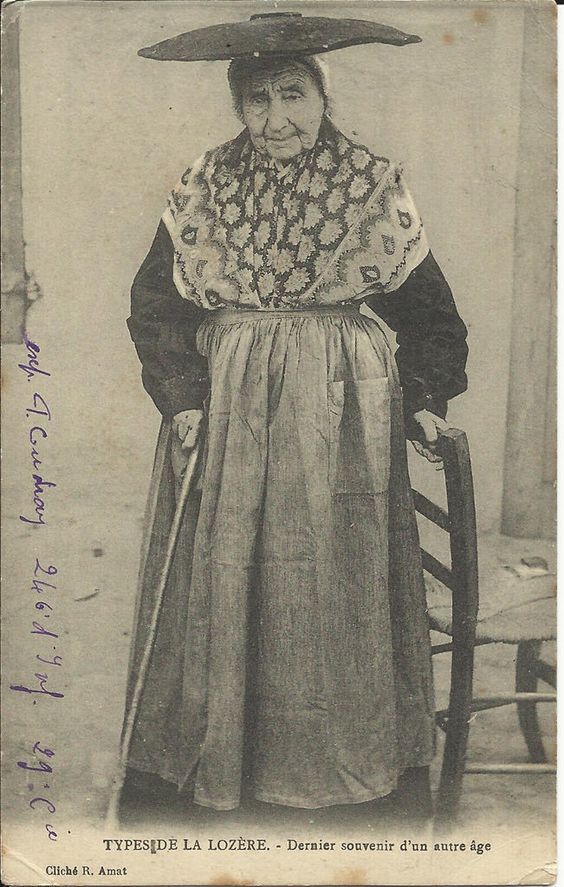

France is, like most nations, multiethnic and multilingual and as a result, every administrative region has a style of folk costume, varying by department. The five corners of the nation have territories in which unrelated languages are spoken; Breton in Brittany, German in Alsace, Dutch in French Flanders, Breton in Brittany, Catalonian in Rousillon, and across the country, various Romance dialects were traditionally spoken. Folk costume is essentially an indicator of identity through dress, and following the rise of romantic nationalism, the peasantry of Europe came to serve as models for all that appeared genuine and desirable.

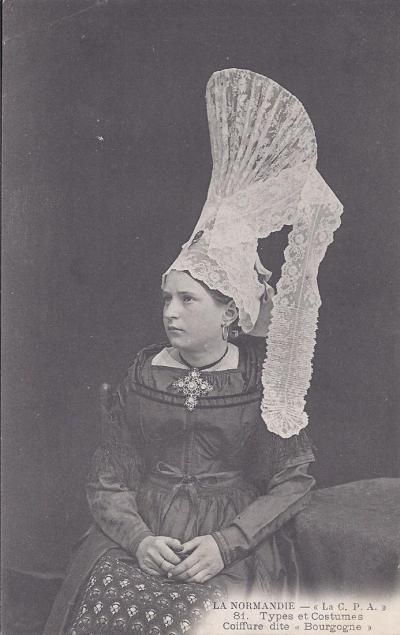

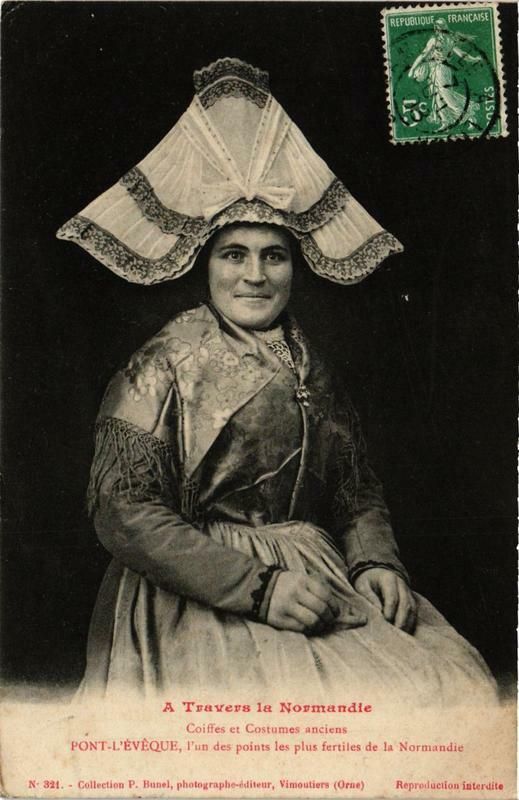

The costumes of Normandy are very famous for their elaborate and gravity-defying giant lace and linen headdresses, made around a simple form of card and wire, secured under the chin with ribbons. They were traditionally made with Normandy lace and handed down, mother to daughter.

While Flanders, Genoa and Venice were the first lace capitals of the world, when the complicated process began to industrialize, France became a leading producer. In particular, the northern region of Calais, the first to have a power loom, has developed a rich heritage of providing lace to luxury designers in France and beyond. Leavers looms, which had been invented in Nottingham, England, during the early 1800s, were smuggled (in pieces) out of the country and to France during the industrial revolution.

By the mid-1800s, Calais (already a hub for linen weavers) hosted more than 100 lace-making companies. Since then, the trade has been carried down through generations by brands like Jean Bracq and Hallette family, which has provided lace for garments worn by the likes of Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor and now Kate Middleton, including for her wedding dress.

The town of Alençon in Normandy is also a hub for its unique lace tradition, totally done by hand. This form of lace-making, which relies on a needle, dates back to the reign of King Louis XIV. (His finance minister realized the country could save a lot of money by producing its own lace instead of importing). Alençon was picked for its already existing lace industry and this new point de France lace became the hottest trend in the royal court.

Lacework was all about how you flaunted your individuality. The art is kept alive today, with artisans spending seven hours per square centimeter of design. A full mastery takes seven to 10 years of training, largely through practice and oral transmission. While the approximately 40 new lace patterns are released every year by Sophie Halette, a French house of tulle and lace since 1887, they are directly connected to the company’s heritage, pulling from its archive of 2,000 patterns, many of which end up on runways like Alexander McQueen, Valentino and Lanvin.

All too often either dismissed as a cultural gimmick to entertain tourists, or discretely referenced in the footnotes of couture collections, folk costume is arguably one of the most underrated sources of inspiration for the fashion industry. So when we credit the Parisian fashion houses as the inventors of true avant-garde style, spare a thought for the “provincial folk” who were doing haute couture before it was cool.