There are so many grand Gilded Age homes in New York’s Hudson River Valley, it led one 19th century wit to comment that ‘one couldn’t throw a stone without hitting a millionaire’s mansion’. Walk along the always fascinating Croton Aqueduct Trail and you can catch glimpses of these luxurious mansions that were once homes to oil barons, railway tycoons, and in the case of the Rockefellers and Goulds, two of the wealthiest families in American history.

But halfway between the picturesque villages of Tarrytown and Irvington, you will find a splendid thirty room Italianate mansion, whose red tiled roof wouldn’t look out of place along the Amalfi Coast. It was once home to perhaps the most incredible and inspiring woman that your history class forgot : Madam C.J. Walker. The blue and yellow New York State Historical Marker placed outside tells you that she was the ‘First African-American Millionairess and a Great Philanthropist.’

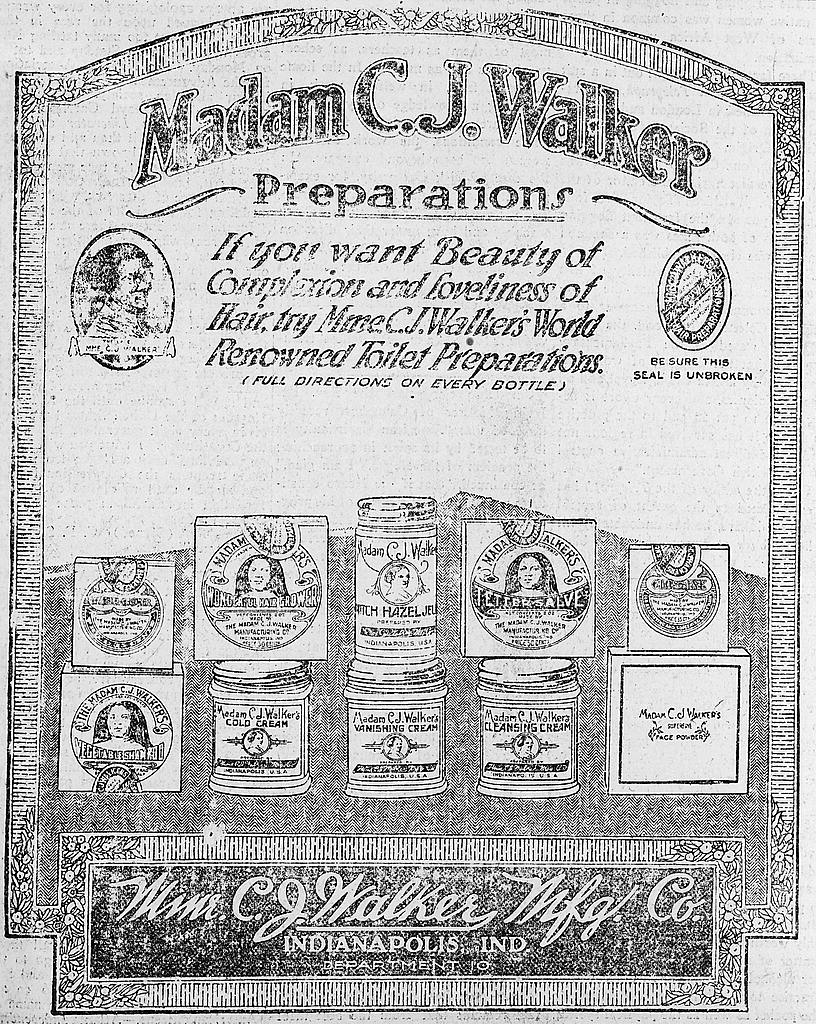

She made her fortune in developing and marketing beauty and hair products specifically for black women. Bur rather than live in wealthy seclusion in her elegant mansion, Madam C.J. Walker created a philanthropic empire to help other African-American women secure financial independence. This is the inspiring story of America’s first self-made female millionaire, which takes place before women had the vote, and nearly half a century before the Civil Rights Act.

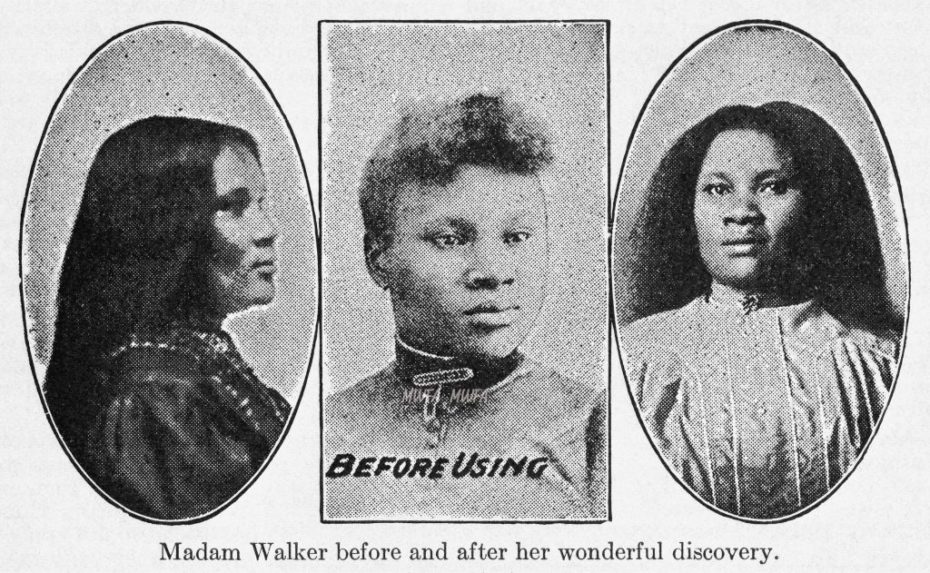

In one of the more remarkable ‘rags-to-riches’ stories in American history, Madam Walker started life in abject poverty with the name Sarah Breedlove. She was born in 1867, just a year after the Emancipation Proclamation. Both her parents and all five siblings had been slaves on the Madison Parish plantation in Delta, Louisiana. After her parents died in the 1870s, Sarah Breedlove was left an orphan at the age of just seven. Moving to St. Louis, she worked as a washerwoman for just over a dollar a day. But the harsh chemical products she worked with to clean clothes began to have an upsetting side effect: Sarah Breedlove started to lose her hair. Suffering from severe dandruff and scalp ailments, she also noticed that the bad plumbing and lack of fresh water in the poorer parts of the city, were causing other Black women to have problems with their hair.

She would later say that a man appeared in one of her dreams, whispering a secret formula to create a scalp conditioner and hair growth product. “Some of the remedy was grown in Africa,” she explained, “but I sent for it, put in on my scalp, and in a few weeks my hair was coming in faster than it had ever fallen out.” It was around this time that she met and married Charles Joseph Walker, a newspaper advertising salesman in St. Louis. Taking the name C.J. Walker and adding a ‘Madam’ to give it some French flair, she called her miracle product ‘Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower’. A naturally brilliant business woman, Madam Walker noticed a vast gap in the cosmetics industry – no one was making or selling specifically to Black women. She proudly put her photograph on the tins of her “Wonderful Hair Grower” and began selling the product door to door.

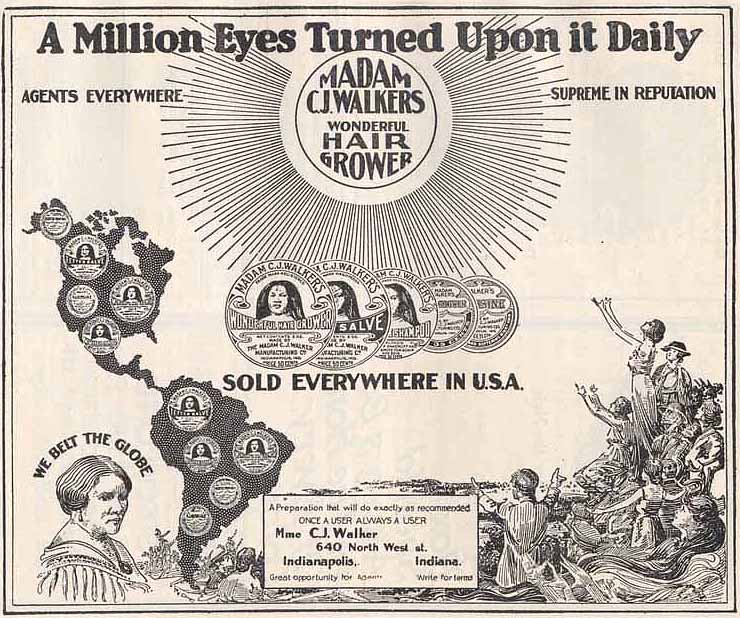

From her initial investment of just $1.50 for the ingredients, Madam Walker’s business blossomed. Using her husband’s experience in the newspaper industry, Madam Walker began advertising heavily in African-American magazines. Soon Black women all over America were using Madam Walker’s line of shampoos, pomades and combs, reviving hair made brittle by poor living conditions. “I made house-to-house canvases among people of my race,” she would tell the New York Times, “And after a while I got going pretty well, though I naturally encountered many obstacles and discouragements before I finally met with real success.”

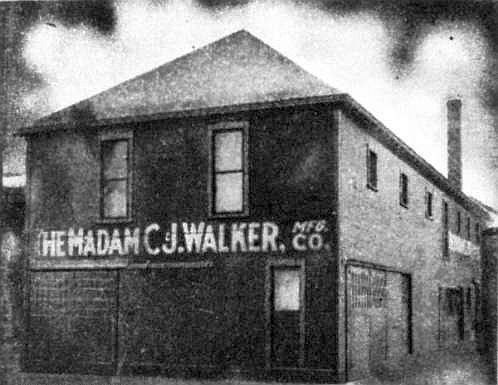

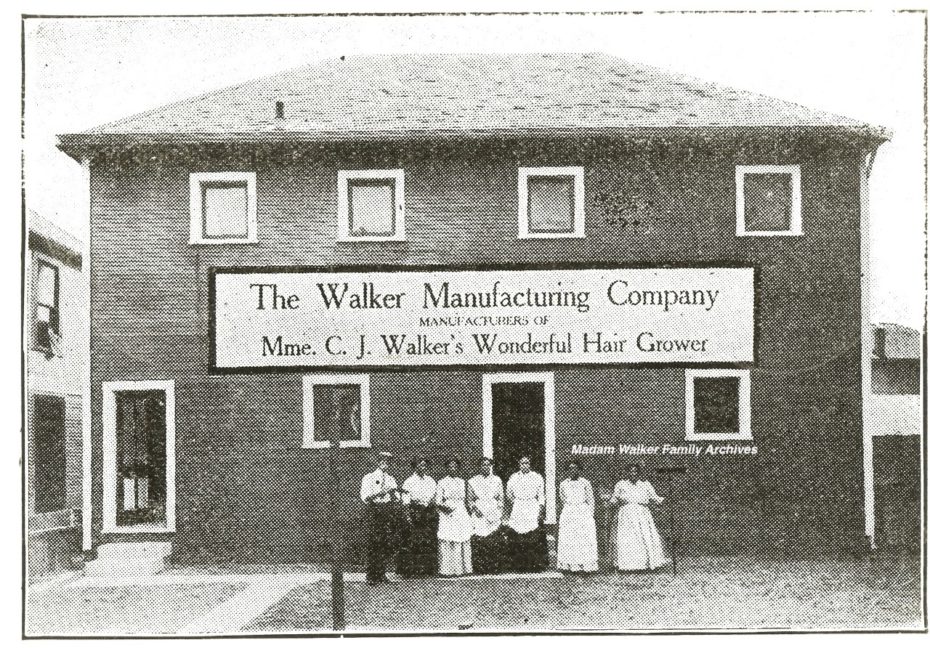

Madam Walker’s success saw her begin to train thousands of other African-American women, who, smartly dressed in a uniform of white shirts, black skirts and black satchels carrying samples of Wonderful Hair Grower, went door to door throughout America. Walker would train her agents not just in grooming and beauty techniques, but in finance and business acumen, enabling thousands of Black women to become financially independent. By early 1910, she had settled in Indianapolis, where she owned her own factory, hair salon and training school.

As this remarkable lady put it, “I am a woman who came from the cotton fields of the South. From there I was promoted to the washtub. And from there I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations….I have built my own factory on my own ground.”

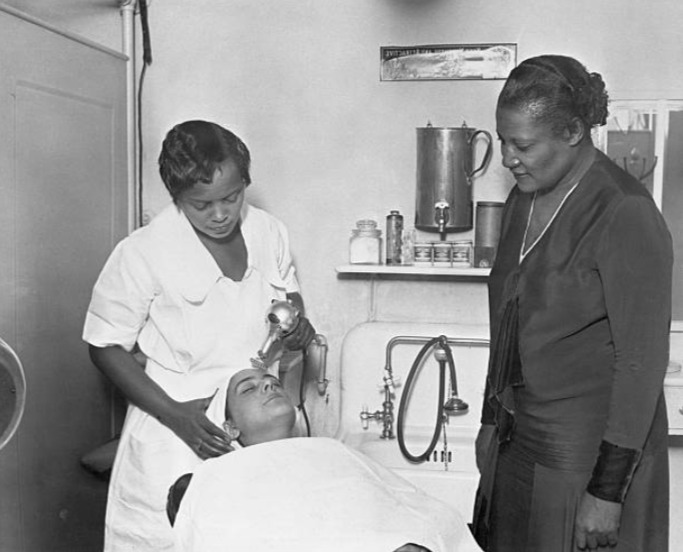

In 1913, her daughter A’Leila Walker Robinson, suggested that Madam Walker should open a beauty school and office in Harlem. They commissioned the first licensed African-American architect in New York State, Vertner Tandy to convert two townhouses into a beautiful Neo-Georgian headquarters. The double-wide townhouse at 108, West 136th Street would lead Walker to comment that, “there is nothing equal to it, not even on Fifth Avenue.”

The grand home was sadly torn down in the 1940s, replaced with a branch of the New York Public Library. Period photographs show an imposing yet elegant red brick town house, complete with a curved facade, balcony with a beauty salon and store on the ground floor. Today the only reminder is a street sign where West 136th meets Lenox Avenue, that was recently renamed ‘Madam C.J. & A’Lelia Walker Place.’

By 1916, at the height of her company’s success, Madam Walker had trained an incredible army of 20,000 women. At a time when wages for African-American women would be just a few dollars a day for often menial work, employees in Madam Walker’s cosmetics empire could earn up to $50-100 a week. The same year she hired Vertner Tandy to build a home even more magnificent than her Harlem townhouse, the mansion in the Hudson River Valley.

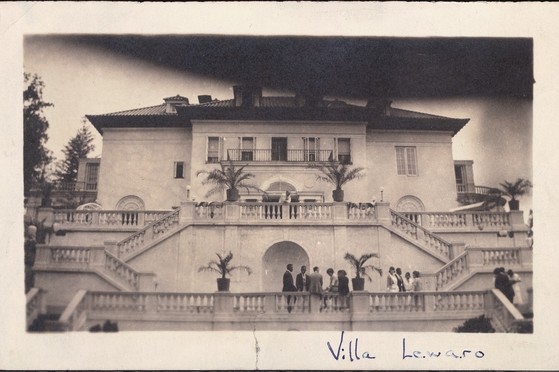

The thirty-four room house cost $250,000, was furnished luxuriously and given the name Villa Lewaro for the first two letters in each of her daughters’ names, Leila Walker Robinson. Madam Walker pronounced it her “dream of dreams” and The New York Times called it “a place fit for a fairy princess.”

A Christmas card printed by the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company showed the staggering change in her hard earned fortune; it featured an image of her Louisiana birthplace alongside Villa Lewaro, or as the company literature put it, “from cabin to castle.”

Madam Walker’s story endures in no small part thanks to the sterling work of her great-great-granddaughter, A’Lelia Bundles, an award winning journalist and author, who founded the Walker archives and has written multiple books about her illustrious ancestor, one of which would loosely inspire the recent Netflix series, “Self Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C.J.Walker.” Bundles explains that, “Walker wished for Villa Lewaro to serve as an inspiration to African-Americans at a time when racist and discriminatory Jim Crow laws denied their basic civil rights and excluded them from educational opportunities and economic prosperity.”

We were fortunate to be able to speak with A’Lelia Bundles about her remarkable ancestor. “The original hair treatment was an ointment a lot like vaseline,” she explains. Back then, working African-American women, “didn’t wash their hair often due to lack of plumbing. Scalp hygiene was very different.” The group breaking formula created by Madam Walker would be based on, “Healthy hair and high quality ingredients.”

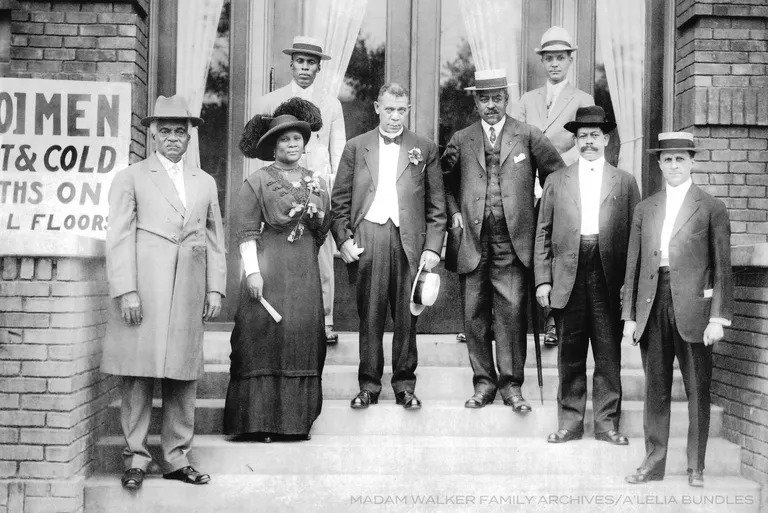

Rather than build her home in seclusion, Walker placed Villa Lewaro prominently on North Broadway, the principle road from New York City to Albany. “The fact that she built her house on North Broadway says a lot. She wanted people to be able to see it,” notes Bundles. “She wanted people to stop saying that Black people cannot achieve.” Walker would create the Madam C.J. Walker Benevolent Association, later the Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Culturists Union of America. “The goal was to bring together all Walker Agents into unions so they could participate in philanthropic and educational events in their communities.”

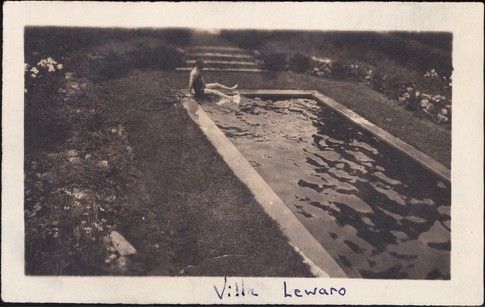

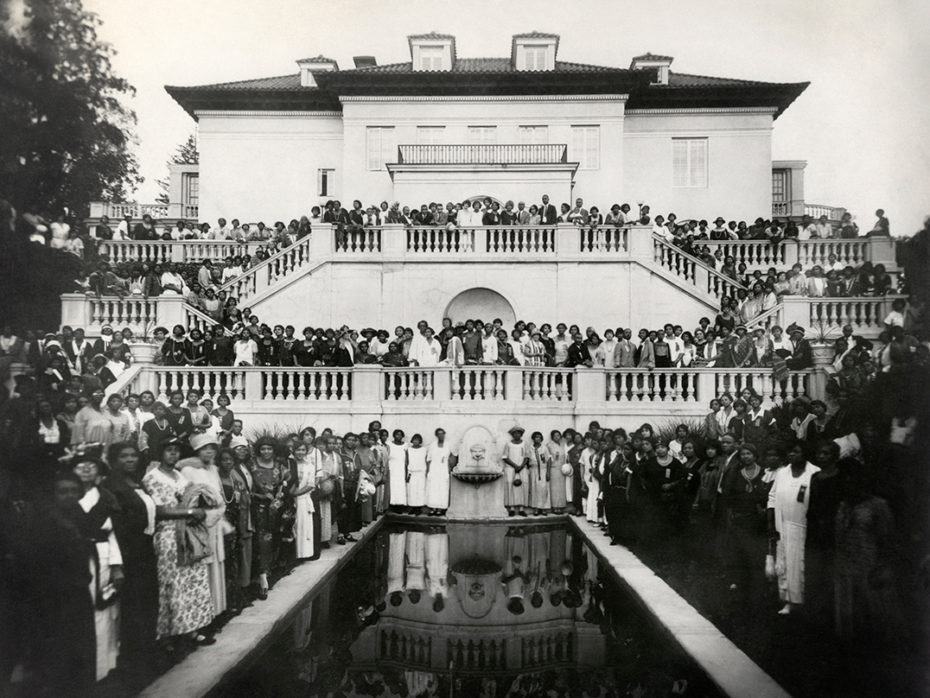

One incredible photograph shows a group shot of Madam Walker’s employees, lining the grand steps overlooking the pool at Villa Lewaro. It shows hundreds of Black women who were given well paying jobs, training and financial security at a time when they couldn’t even vote, and all thanks to the orphaned washerwoman. “I got my start by giving myself a start,” Madam Walker told the New York Times in 1917, by which time she was America’s most successful, self-made female entrepreneur. “They were farm workers and household domestics from Chicago, Dallas, Kansas City,” explains Bundles, “Her business allowed them to have an independent income not dependent on white employers, but give them economic empowerment.”

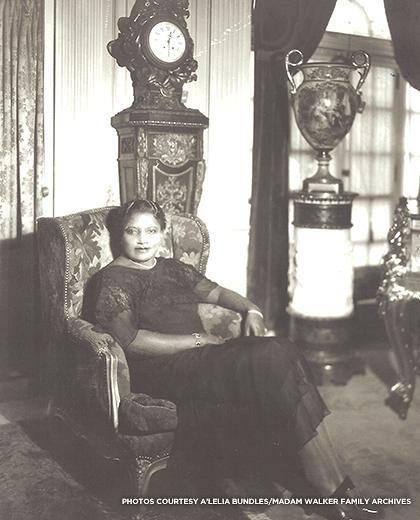

Villa Lewaro’s grandeur would be a testament to what was possible through hard work. As Bundles explains, “visitors would enter through a porte-cochere…..the herringbone hardwood floor was covered by a Tabriz carpet. Italian tapestries hung from the walls. In the center of the room, a Cartier bronze sculpture of a jaguar sat atop a large oak table.” But the mansion was to be more than just the lap of luxury: Madam Walker intended Villa Lewaro to become a gathering place for other African-Americans to meet and “pursue their dreams.”

Amidst the privilege and wealth of one of New York’s grandest neighbourhoods, one likes to imagine the stir Madam Walker caused. “Impossible!”, exclaimed the headline in the New York Times in November, 1917, “No woman of her race could afford such a place.” One of the few surviving photographs of this incredible woman is fantastic: it shows her and her daughter with some friends, also African-American women, in a state of the art, high powered car, driving around town. “She owned a Model T Waverley,” explains Bundles, “it was state of the art, driving today she would now be in a Tesla.”

Madam Walker passed away in 1919, one of the wealthiest African-American women in America. She bequeathed Villa Lewaro to the NAACP, but the toll of the Great Depression would see the magnificent mansion pass through several owners’ hands,. Today it’s protected by the National Trust for Historic Preservation and while the home is not open to the public, you can tour the decadent mansion online.

As director Brent Leggs says, “Villa Lewaro continues to live up to its role in inspiring all of us to reach our highest potential. This place is truly a ‘dream of dreams,’ as Madam Walker called it — and we must not forget that such an unprecedented achievement took place in an era when neither women nor African-Americans were considered full citizens.”

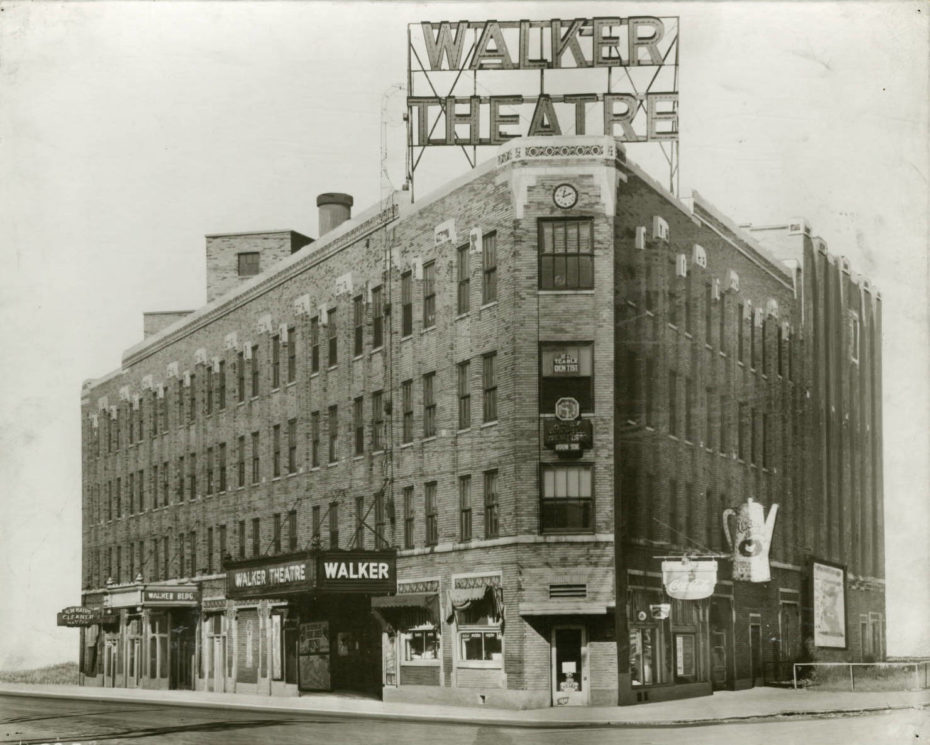

Madam Walker’s Indianapolis headquarters and manufacturing plant still exists today as a magnificently restored Art Deco theatre and cultural centre. Her former grand home, Villa Lewaro has also been expertly restored and preserved amongst the other mansions that line the Hudson River Valley. But both are much more than just buildings.

As A’Leila Bundles explains, “every time I walk through the doors of Villa Lewaro, I always take a moment to imagine the ancestors and the magic they must have felt in these rooms. Villa Lewaro is one of the few remaining tangible symbols of the astonishing progress made by the first generation after Emancipation.” Of that generation, surely no one was as remarkable or inspiring as Madam Walker, who said she built the house, “to convince members of my race…what a lone woman accomplished and to inspire them to do big things.”