Full disclosure, we never gave the Periodic Table much thought – it remains in our memory as a clunky patchwork of confusing titled squares taped to the back of our school chemistry folder that our teachers would occasionally torture us with for a pop quiz on the elements. Walter Russell however, a 1920s Renaissance man, did give the Periodic Table a lot of thought, so much so, that he was inspired to reimagine it in a dramatically different and artistic form, adding two missing elements that would later lead to the development of the atom bomb. This, coming from a guy who never advanced beyond a grade 4 education. But there was something about Walter. The great Serbian-American inventor, Nikola Tesla was an admirer, and was so awed by Russell’s philosophy on cosmology and the nature of the universe that he told him to lock his findings in a sepulcher for a thousand years, because in his opinion, mankind was not ready for it. Keeping up with the many lives of Walter Russell is as dizzying as attempting to understand his extensive archive of mesmerising New Age diagrams. He was an eccentric scientific philosopher, renowned sculptor and impressionist painter, an author, musician, equestrian, an architectural developer – and, perhaps the cherry on the cake – he is credited with introducing figure skating to America. So without further ado, it’s time to get better acquainted with this under-the-radar 20th century visionary.

In 1871, when Walter Russell was born in Boston, Massachusetts, astronomy and nuclear physics were only just in their infancy. Ernest Rutherford was born in the same year and Marie Curie four years earlier. A young Walter left school at age 9 and went to work to later put himself through public college and travel to Belle Époque Paris where he attended a private art school. When he returned to New York in 1894, he was an accomplished painter and received much praise for his The Might of Ages in 1900, a large heroic landscape painting depicting some of America’s national achievements which represented the USA at the Turin International Exhibition. By 1903, he had illustrated and published three children’s books and was a member of the prestigious Author’s Club. He was not just a remarkably successful and prolific young artist, but also a facilitator for his fellow artists and was involved in designing a series of New York artist’s hostels and cooperative developments. These were large grand urban buildings with around 15 floors of studio space, such as the gothic pile Hotel des Artistes at 1 West 67th Street where Russell can also allegedly be credited with creating the modern-day concept of the duplex and penthouse apartment. But Walter wasn’t one to often concern himself with credit, and subsequently much of his architectural work, among other achievements, went undocumented and were ultimately forgotten despite reportedly having designed and built twenty million dollars worth of real estate in New York City (including the first Hotel Pierre and Alwyn Court, one of the city’s most ornate buildings to date).

The making of Walter Russell was perhaps not so much of a flowering than a rumbling eruption. His upbringing and learnings were far from the conventional, they were a roller-coaster ride of bizarre events. He had had his first ‘illumination’ experience at the age of 7, an event of personal introspection and out-of-body experience. At 14 years old he was reportedly pronounced ‘dead’ after an of attack of Black Diphtheria, but claimed ‘was asked to return’ during another out-of-body experience. He claimed at some point to have been struck by lightning.

Much later, at age 50, the year 1921 would be a milestone for Walter: he commenced his self-study of the sciences and was the first to coin the phrase ‘Electromagnetic Wave Universe”. In the same year he met with Nikola Tesla, the electrical engineering genius, who famously suggested the world was not ready for Walter. Whether Tesla was concerned for mankind, personally envious or utterly bemused, we shall never know, but there are various works, inventions and discoveries by Tesla that remain unpublished and untested to this day for reasons unknown.

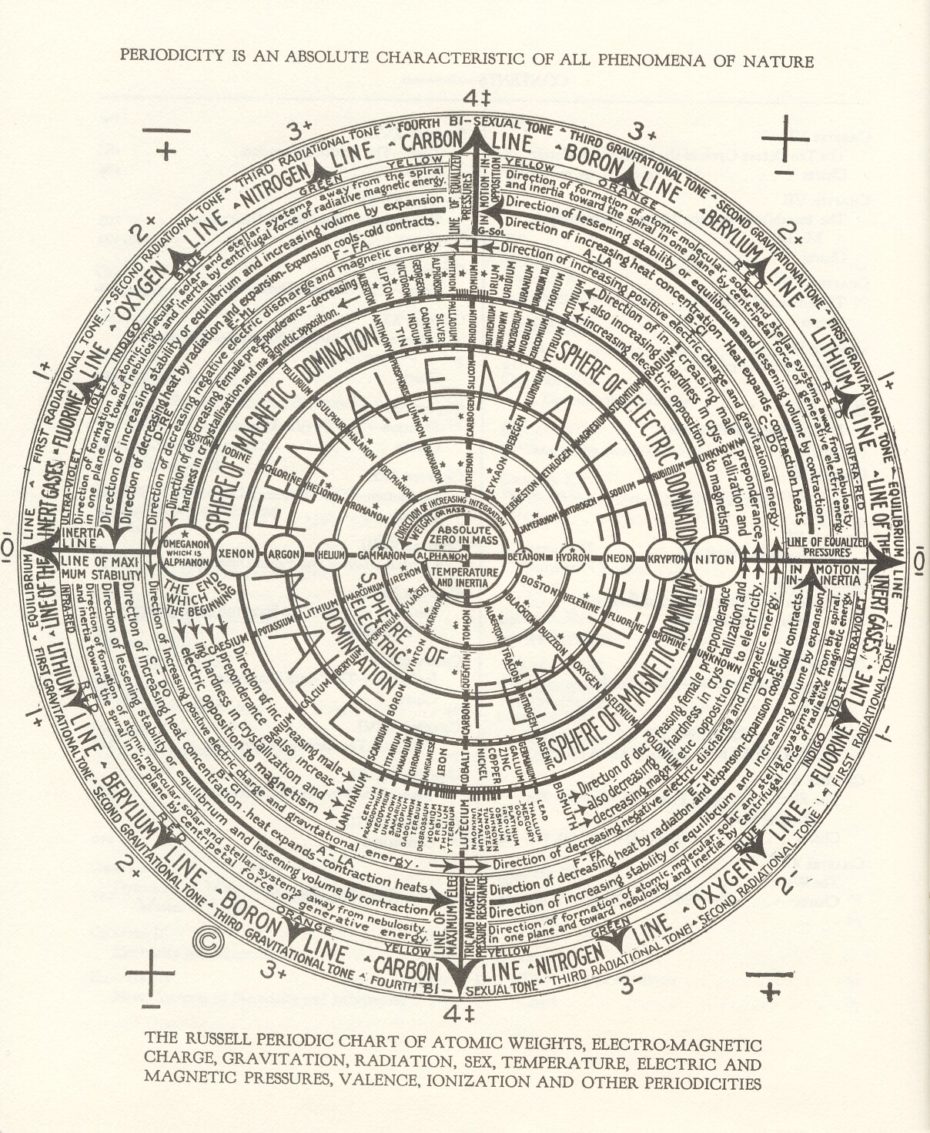

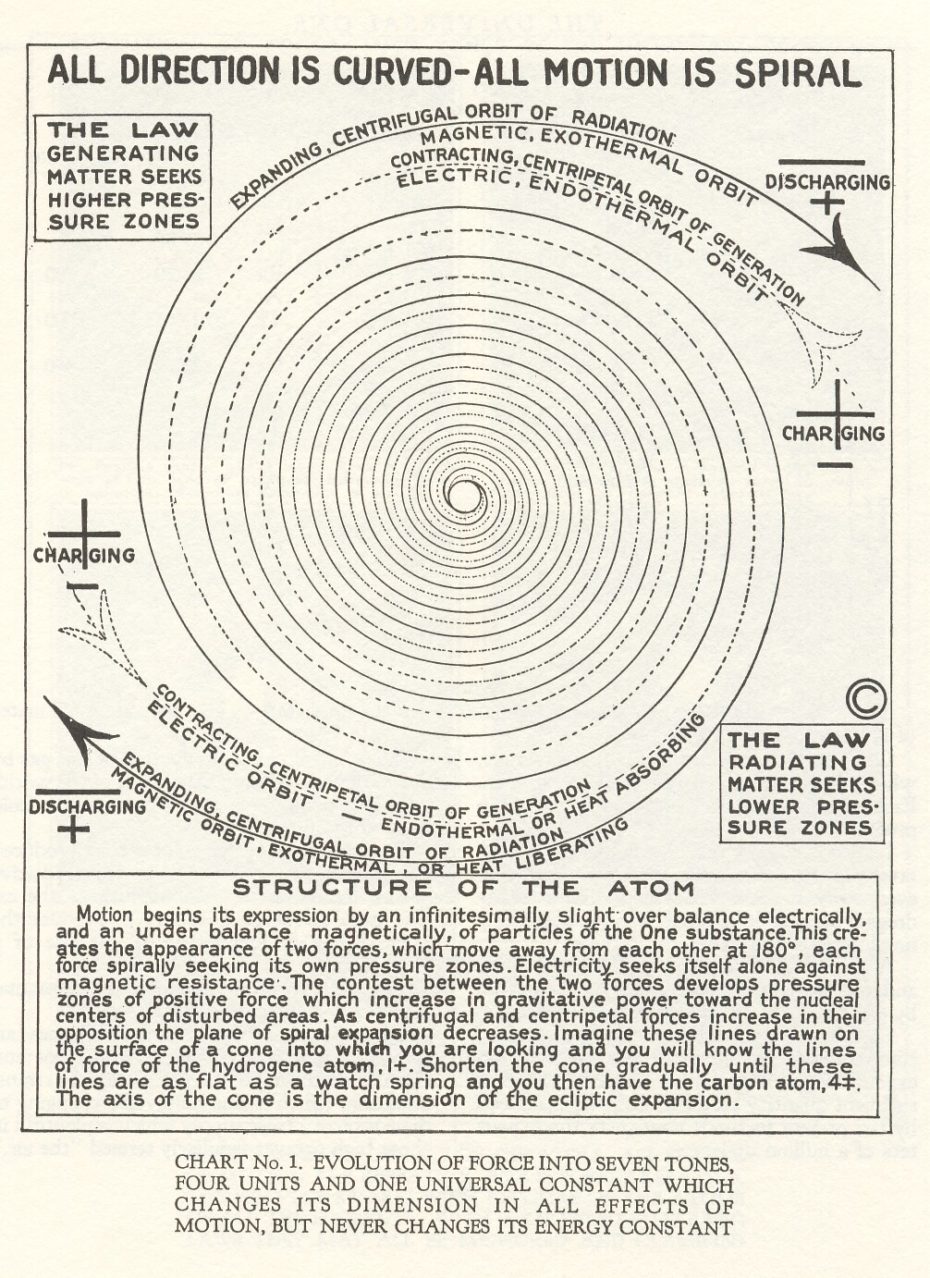

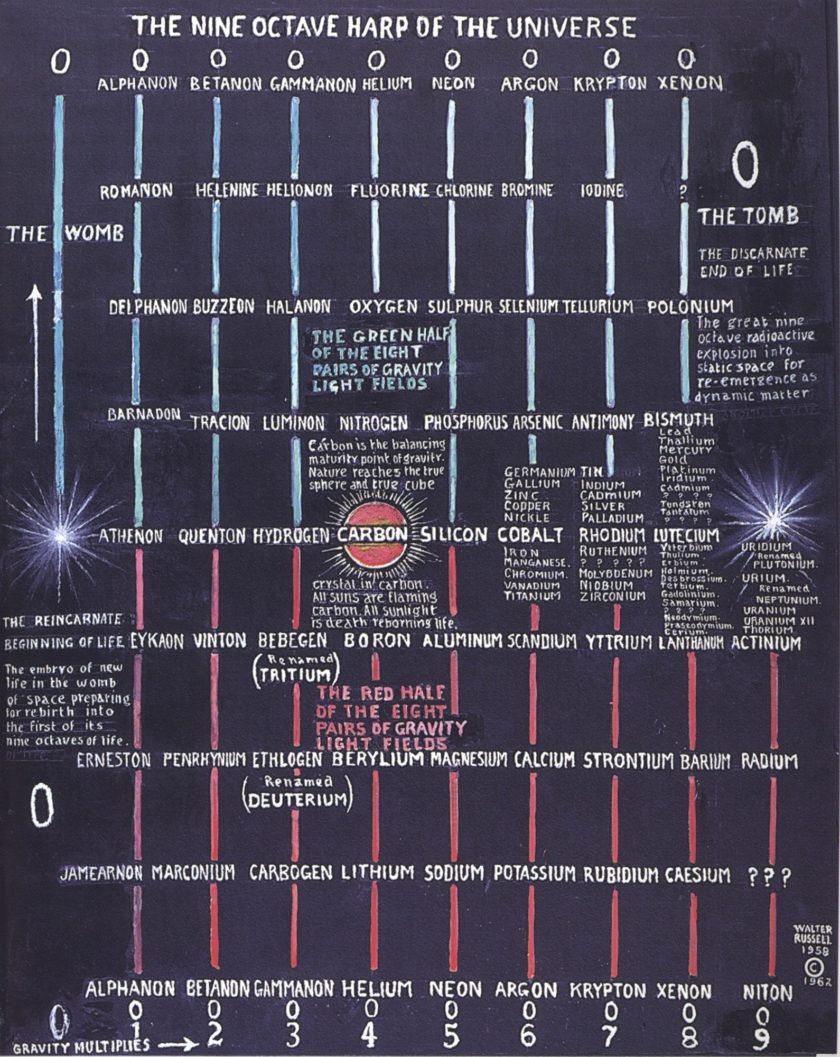

Five years later, Walter published and copyrighted his revolutionary spiral shaped Periodic Chart of the Elements. This dramatically different and artistic representation predicted new elements and shocked the scientific world by claiming there were in fact atomic conditions below Hydrogen and additionally, many more heavy radio-active elements to be discovered. This was not only a brilliant rational analysis, but also graphically rich and convincing. Walter saw the spiral form, now so familiar to us, as the primary arrangement for the atomic and molecular assemblies of the universe. His reward came in 1927 when he was elected president of the Society of Arts and Sciences.

The year 1929 brought another illumination: this time he locked himself in isolation for 39 days and became aware of a “greater colour wave’. He went on to write; “It will be remembered that no one who has ever had [the experience of illumination] has been able to explain it. I deem it my duty to the world to tell of it.” Walter believed he could now “perceive all motion’ and ‘was aware of all things”.

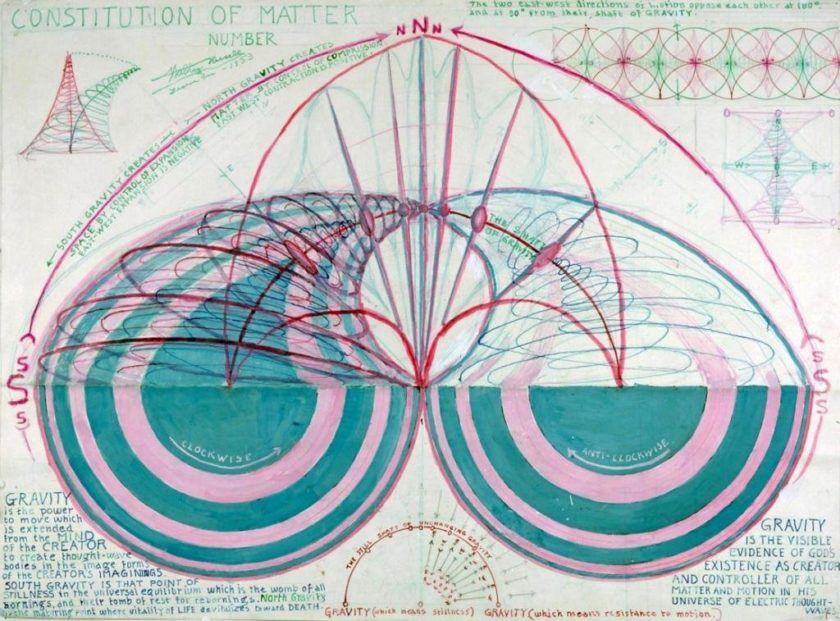

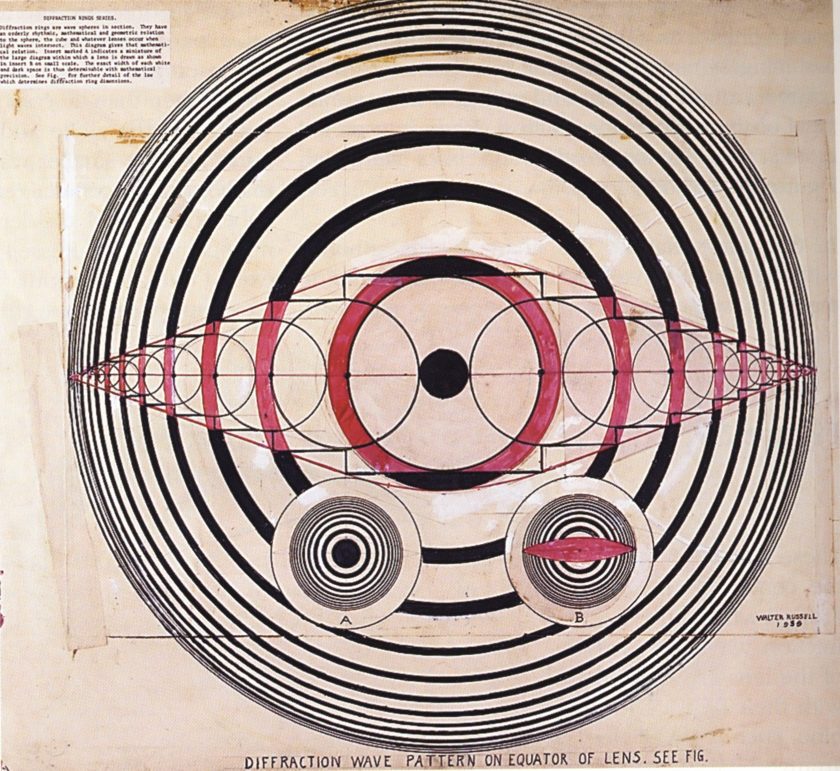

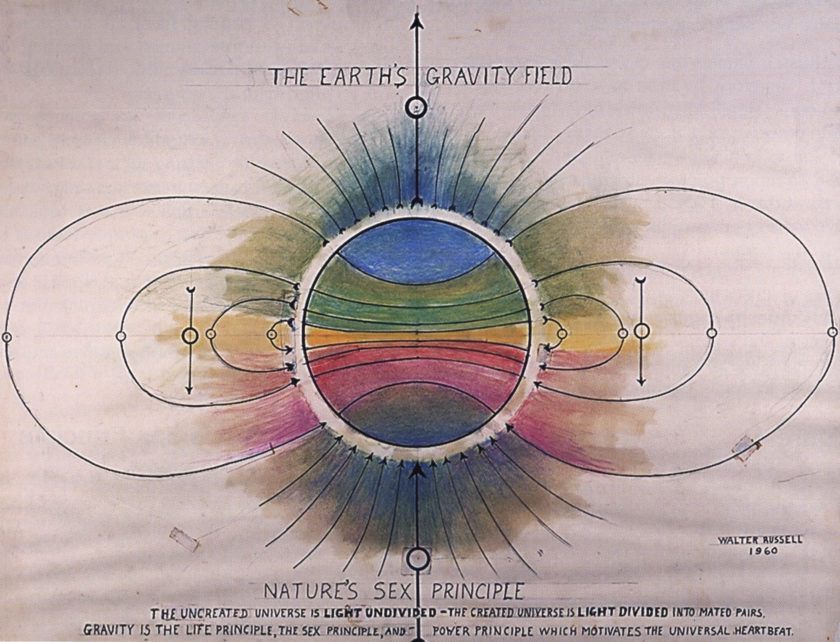

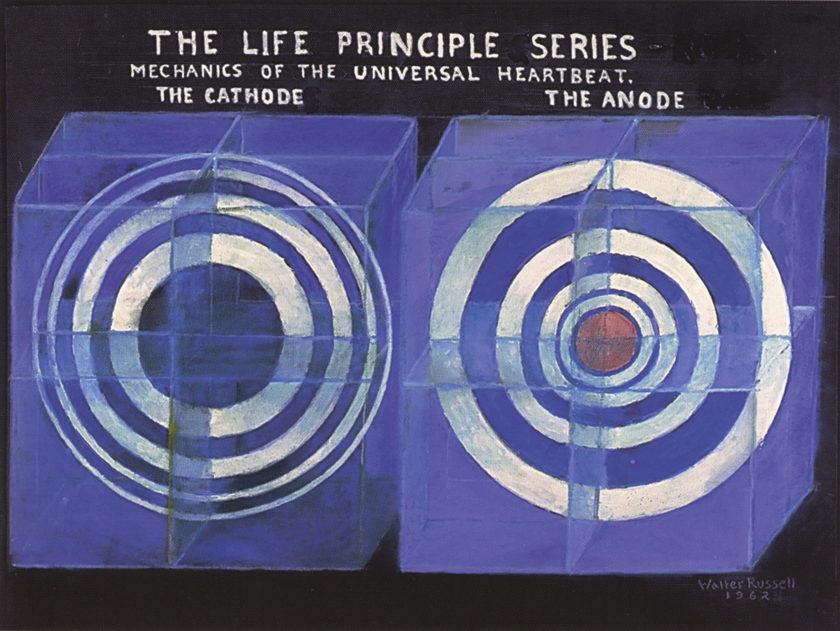

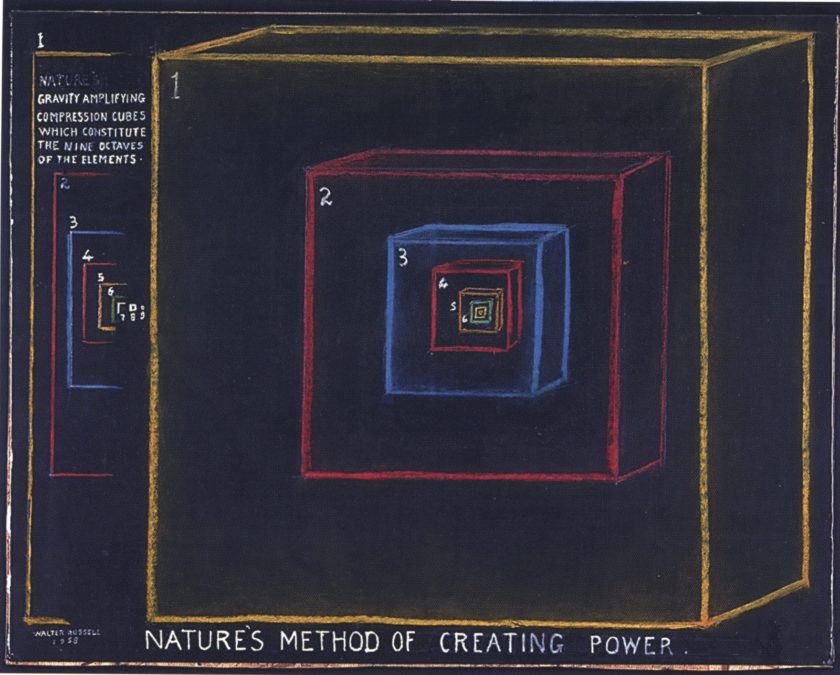

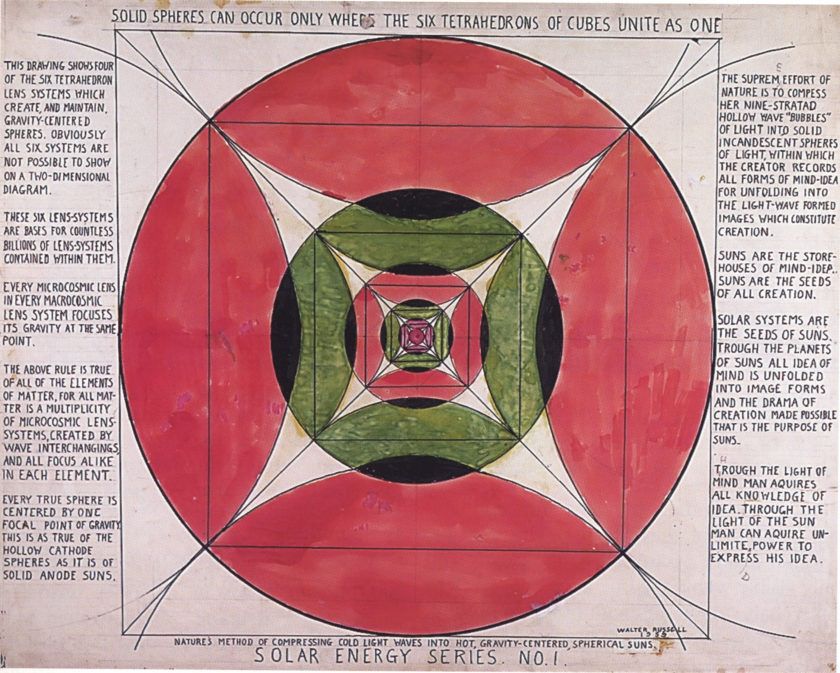

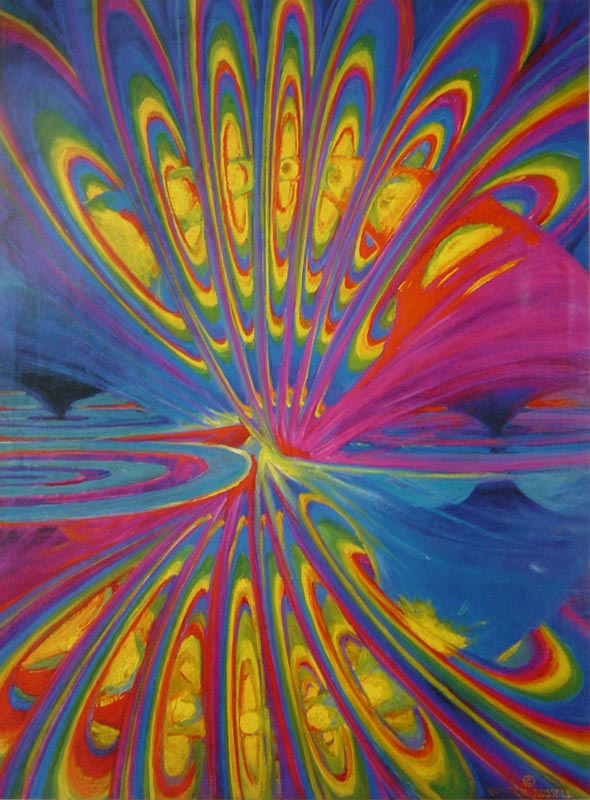

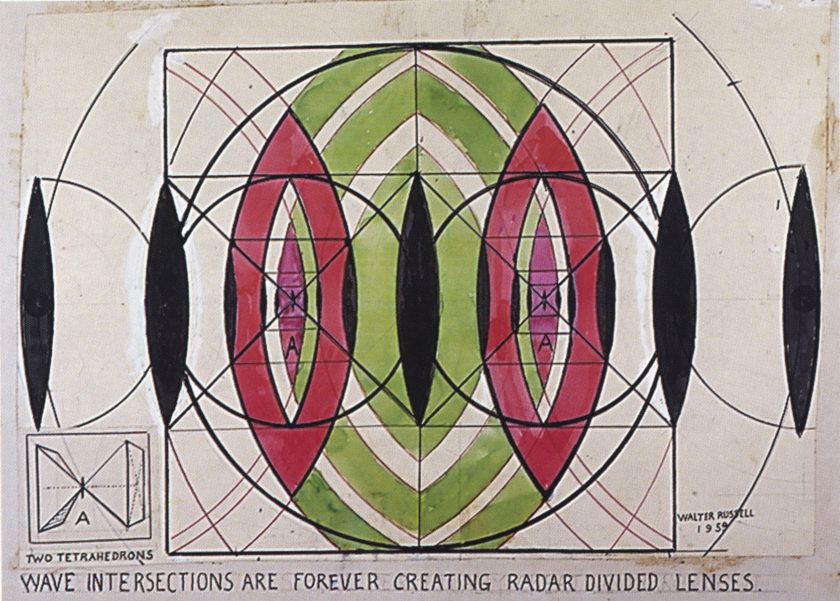

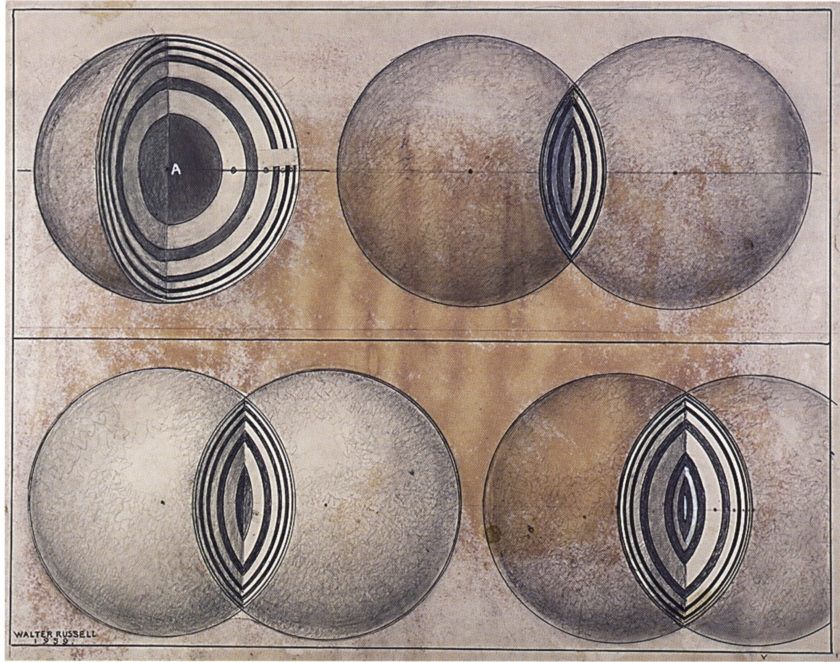

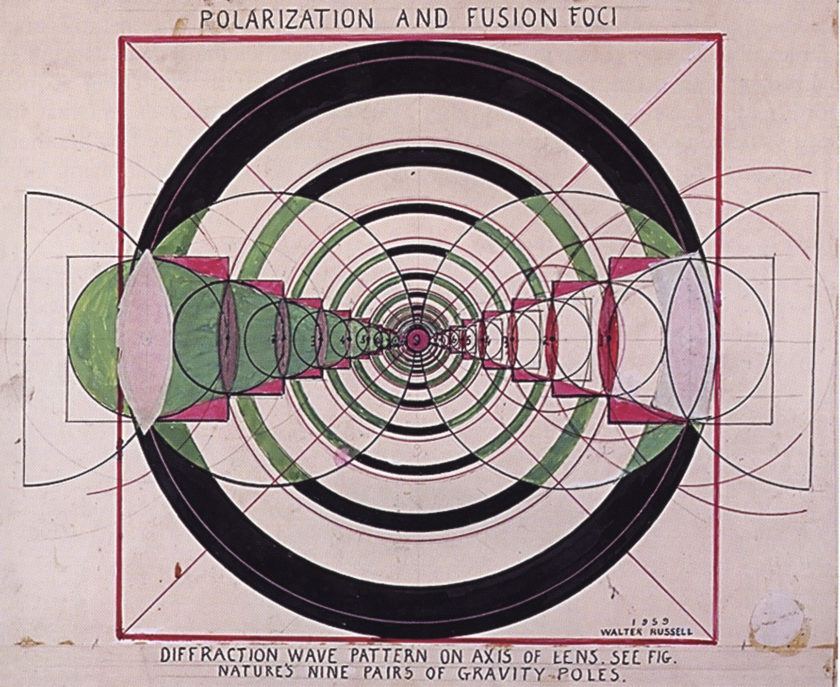

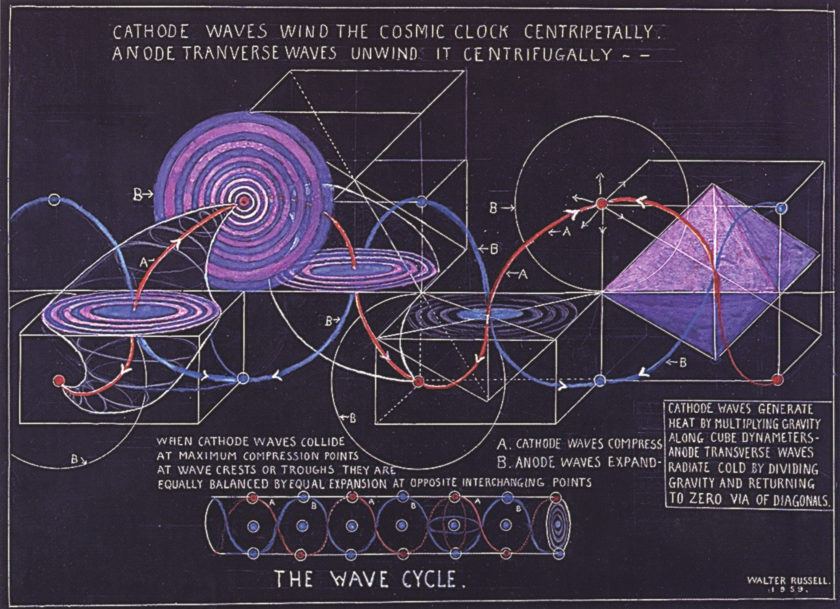

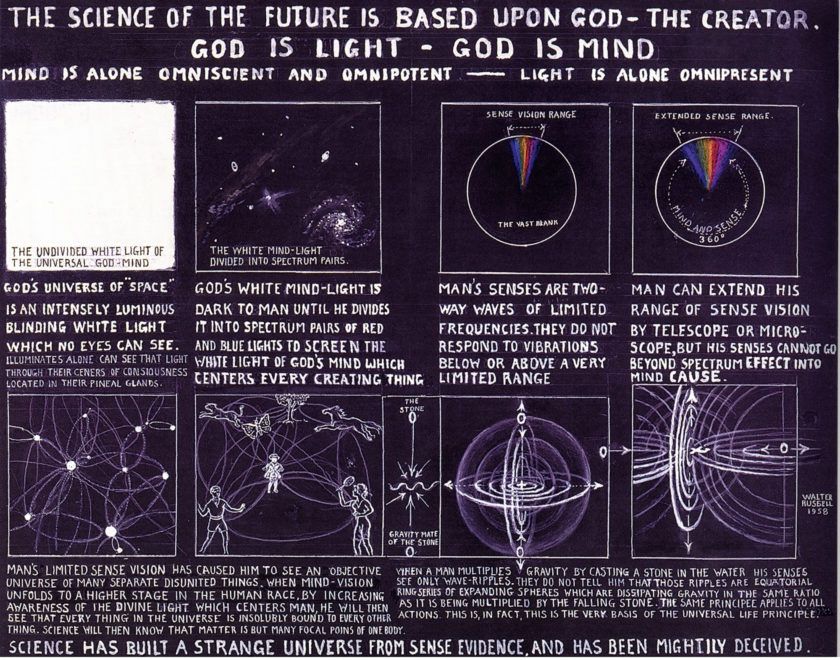

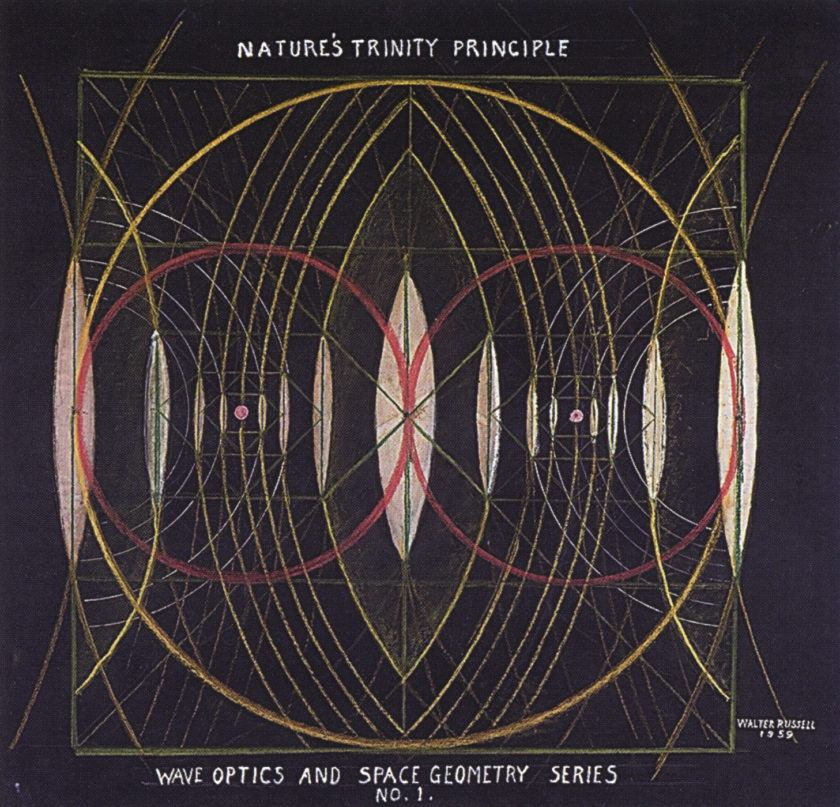

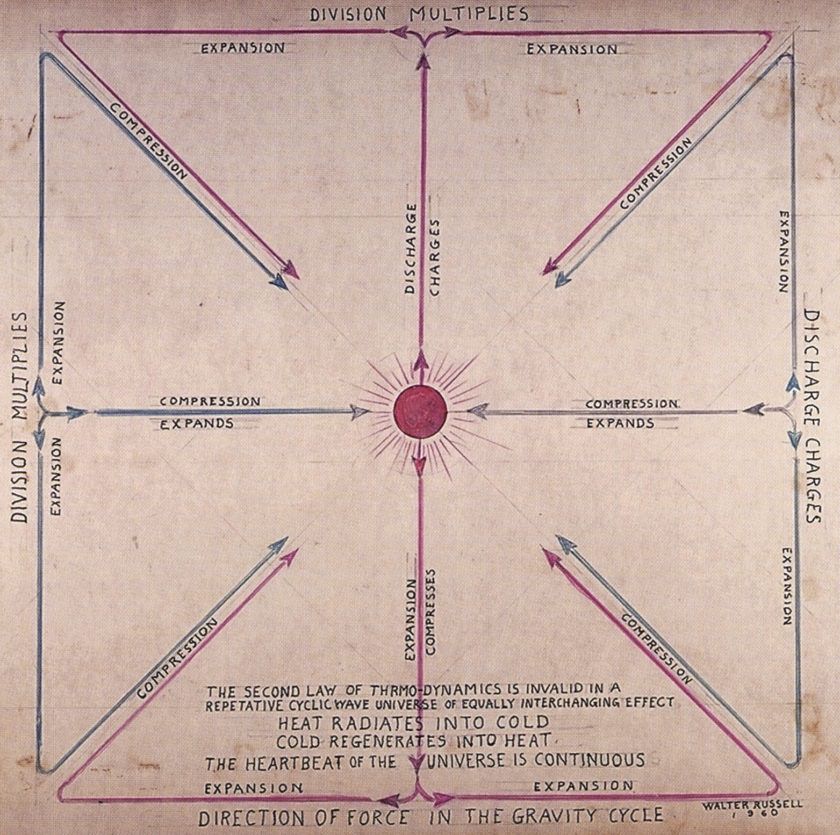

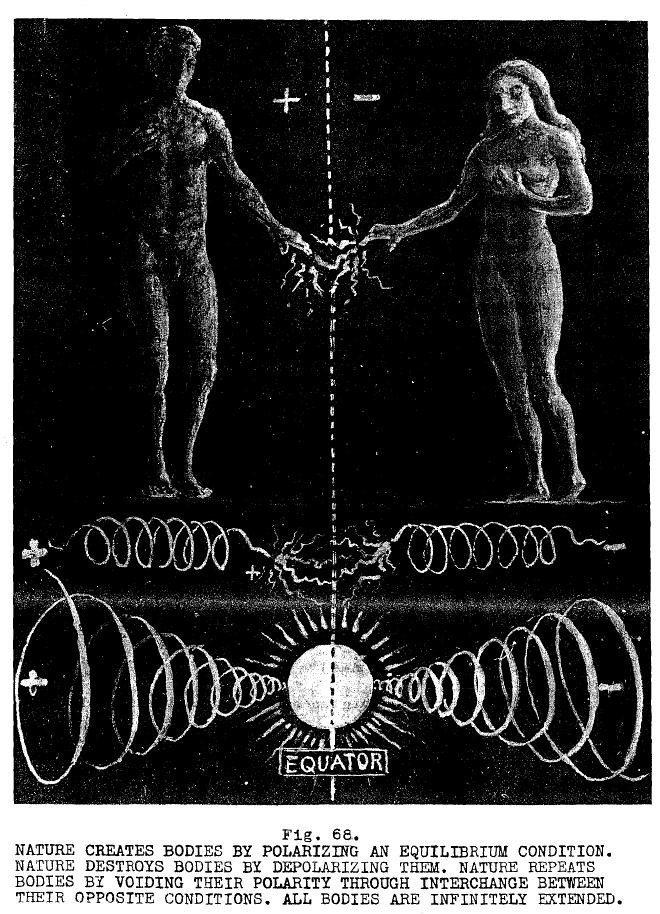

Walter’s artistic ability let him illustrate his three-dimensional universe as a two-dimensionlal graphic, but almost always drawn in his typical confusing style on a single sheet of overlaid diagrams and populated with cryptic notes, so complex that only Walter ever understood what was going on. (If only Walter had had a 3-D drawing programme to build his models). He would go on to produce dozens of these puzzling and artistic graphic representations of his theories of space, time, motion and the cosmos – a mystery to most mortals to this day.

Obsessed with his view of the physics of light, he was a pioneer of ‘new world thought’ and pumped out over a dozen books around the subject, such as The Universal One (1926), The Book of Early Whisperings (1949), A New Concept of The Universe (1953) and The Electrifying Power of Man-Woman Balance (1960). In what was perhaps his most profound publication, The Secret of Light (1947), he stated, “Man lives in a bewildering complex world of EFFECT of which he knows not the CAUSE. Because of its seemingly infinite multiplicity and complexity, he fails to vision the simple underlying principle of Balance in all things. He, therefore, complexes Truth until its many angles, sides and facets have lost balance with each other and with him.”

Walter Russell would develop his atomic theories to encompass all of creation, from the invisible subatomic particles to the vast spinning galaxies where he saw the patterns of nature repeating themselves time and time again. He believed that all matter was a manifestation of light, that everything was related, relative, paired and in balance.

His diagrams to support his theories are artworks in themselves, complex intersecting hoops, coloured and pulsating radiation illustrations, twisting pyramids and polygons – all rather reminiscent of abstract geometric art of the period and even of modernist Kandinsky’s works or his 19th century female predecessor, Hilma af Klint.

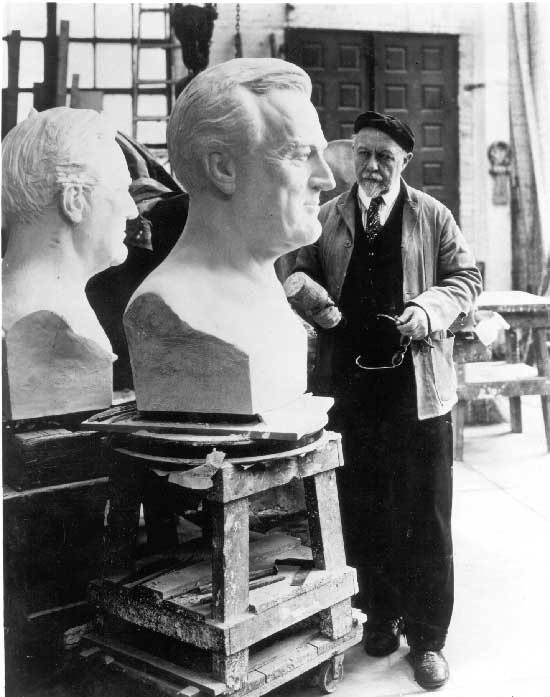

Whilst never recognised as a truly great painter, he would continue to explore his artistic ability as a nationally celebrated sculptor. His output included numerous larger-than-life size busts of the great American heroes such as General MacArthur, Thomas Edison, Mark Twain and George Gershwin, and is recorded as a guest at the White House, as both an official painter and official sculptor.

Walter, an established figure in society at the time, was able to engage with the leading scientific minds of the day, notably Nikola Tesla, Thomas Edison and the famous physics experimenter Dr Robert Millikan. In the 1930s, he was employed as a motivational speaker by IBM (founded in 1911) which was at the forefront of emerging technologies and new age machines. Russell was also a member of the Twilight Club, named after the evening gatherings of the great and the good from New York society, whose members famously included John Burroughs, Mark Twain and Andrew Carnegie.

Figure skating, as briefly mentioned earlier, was one of Russell’s more “leisurely” passions. He founded the New York Skating Club and organised an annual skating carnival at Madison Square Gardens. He invited the world’s most prestigious instructors to his club to help see the art of figure skating take root in America, all while winning competitions well into his late sixties. And did we mention he was an accomplished equestrian and horse breeder? Where did he find the time?!

At the age of 77, he left his wife of fifty years in 1946 after receiving a mysterious phone call from a Daisy Stebbing, an English immigrant, model and business woman who had also just happened to have read Glenn Clark’s biography of Walter, The man who trapped the Secrets of the Universe (1946). Walter married the youthful and admiring Daisy, aged 44, in 1948 amid a scandal. The new couple took to the road, travelling the USA to find a home for the Walter Russell Foundation, eventually finding their new base in an abandoned summer palace of a former railroad magnate. The neglected mountaintop Italian Renaissance Revival villa in Waynesboro, Virginia, known as Swannanoa, became a foundation and museum for his work (now the University of Science and Philosophy). At Swannanoa, the couple continued to publish their theories, and at this point they were particularly concerned with the radiation legacy from nuclear fuels, which they warned against in their book Atomic Suicide? (1957).

Daisy, who changed her name to ‘Lao’ after a Chinese illuminate, died in 1988, while her soulmate Walter had by then long since departed the earth (1963) for the wider cosmos. Upon his death in the USA, CBS Television had described him as ‘the Leonardo da Vinci of our time’.

Despite having written extensively on scientific topics, the eccentric polymath has often been dismissed as an outsider pseudoscientist and his ideology is rarely accepted by any mainstream scientific circles today. But as Paul Prudence of Data is Nature points out, “As Art-Brut is to Art, so characters like Russell and Lao are to traditional mainstream science, and so they are essential. It might just be the case that Walter Russell’s genius, and his diagrams, can only be decoded at a later moment in time”.

Walter Russell may indeed have been way ahead of his time, as Tesla suggested. He firmly believed he had the ability to see the very essence of the creation, and also believed that every man has consummate genius within him. “Mediocrity is self-inflicted and genius is self-bestowed”, he said. But if all else fails, the good news is, there’s always figure skating.