Unless you are Taiwanese, you probably don’t know that Taiwan is inhabited by indigenous Pacific Islanders. Currently, there are 16 recognized tribes on the island, comprising 2.4% of Taiwan’s population of 23 million people, comparable to the native population in the United States (2%). Archeological evidence shows that indigenous people have been on Taiwan for at least 8,000 years. At some point between 3,000 and 1,500 BCE, groups of indigenous people set sail from Taiwan and settled all the Austronesian islands, from Madagascar all the way to Hawaii. The indigenous people of Taiwan are the ancestors of the Maori.

For the past five hundred years, Taiwan’s indigenous people have had to put up with successive waves of colonizers. First came the Dutch in 1623. They brought the first Chinese over to the island because the indigenous people flat out refused to work for them. When the Qing Dynasty took over the arable Western half of the island in the late 1600s, the indigenous people continued to resist, leading to a Qing dynasty saying about Taiwan, “Every three years an uprising; every five years a rebellion.”

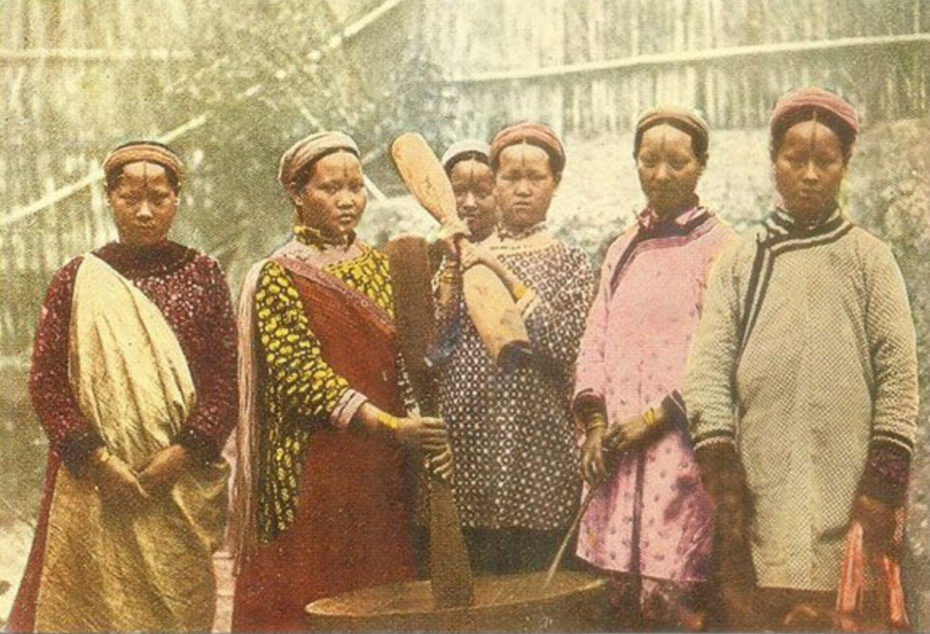

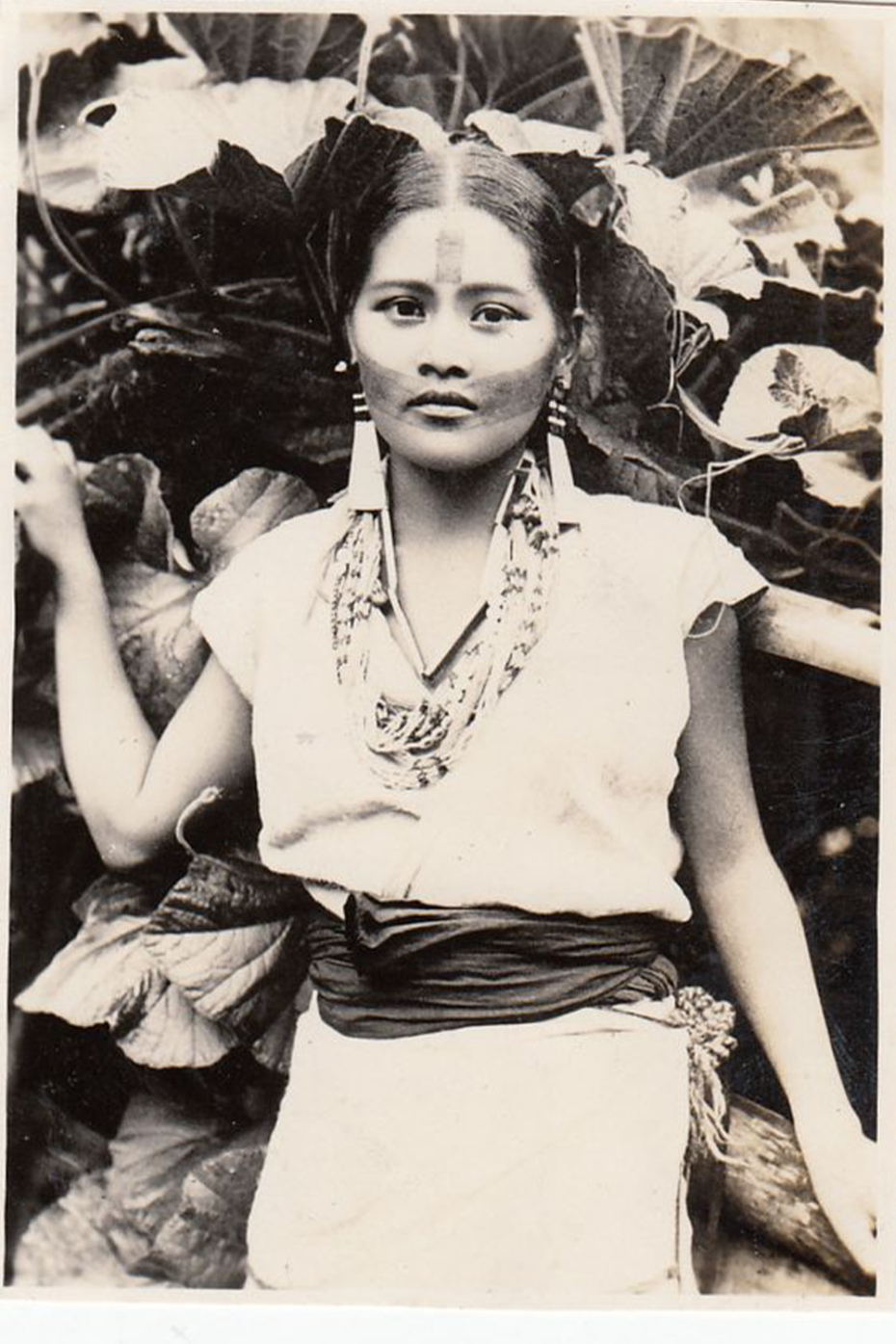

The indigenous people are also matriarchal. Indigenous men are absorbed into their wives’ family and inheritance is matrilineal. Many of the indigenous tribes have female chiefs. It’s the opposite of Confucian patriarchy and astonished early Chinese travelers called Taiwan the Kingdom of Women – the Chinese equivalent of the Land of the Amazons.

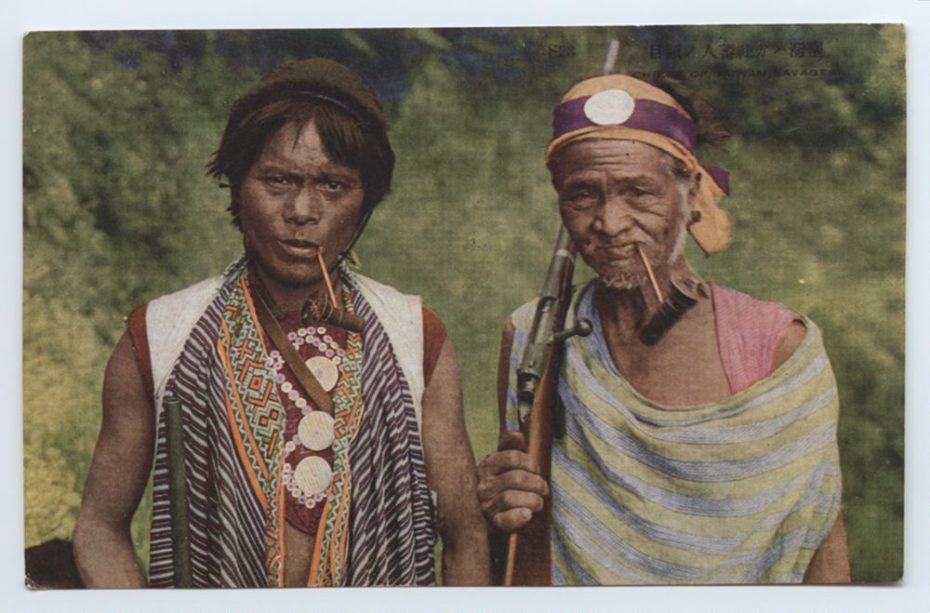

Did we also mention that they were headhunters?

In 1895, the Qing Dynasty lost the Sino-Japanese War and they were super happy to cede Taiwan and all its trouble-making natives to Japan. It was the Meiji Era, and Japan had just started following in the footsteps of European super-powers. To be a super-power in those days, you needed colonies. Japan was ecstatic to receive its first colony and start flexing its muscles.

Like all colonizers, Japan sought to establish dominance over its subjugated peoples. Most of the Taiwanese people of Chinese descent shrugged at a different set of masters. As long as they could keep farming, they didn’t care. The indigenous people, however, resisted being “civilized” and put up a prolonged fight. To quell the natives, the Japanese employed a variety of the usual tactics: outright military suppression, forced assimilation into Japanese culture, and land grabbing. They also discovered that postcards could be a deceptively innocent means of colonial propaganda.

Mass-produced postcards were very new at the turn of the 20th century. The Japanese government produced hundreds of thousands of postcards of their new colony, showing the marvelous ways that they were modernizing the cities and developing trade. With photography pretty much non-existent on Taiwan before the 1920s, the picture postcard was the dominant source of photographic imagery of the island.

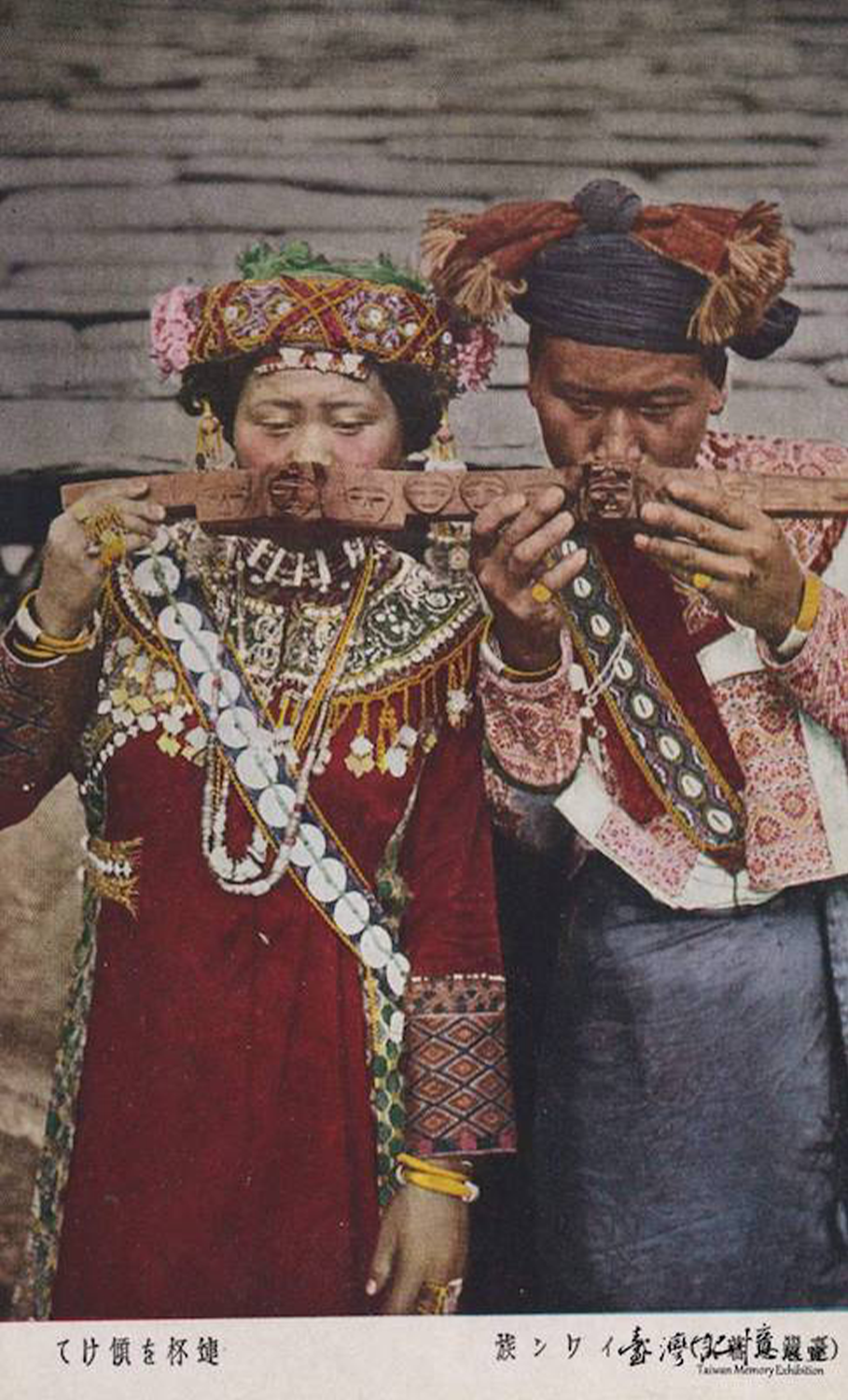

Most of the postcards that the Japanese produced featured the indigenous people on Taiwan. Under influence from Western anthropology, Japanese scholars were sent out to study and photograph indigenous people. These photographs were used to produce thousands of postcards. By then, the majority of the population was Chinese, but you would never know this from Japanese postcards. The postcards promote a colonist legend of Taiwan as an isolated island of savages benefiting from the civilizing effect of Japanese rule.

Knowing all of this doesn’t make the postcards less marvellous. They’re a source of nostalgia for both indigenous people and Taiwanese people of Chinese descent, who long for a once-upon-a-time before industrialization on the island. The postcards also provide iconography for indigenous pride and evidentiary support for indigenous land recovery. In other words, though they are relics of a colonial past, the postcards have been reclaimed by the Taiwanese to affirm their unique history and culture.

A glance at even a few of these postcards show the richness of indigenous culture in Taiwan. A hundred years later, they still convey indigenous defiance and pride.

About the Contributor