At less than a fifth of a square mile, The Vatican City is officially the world’s tiniest country. As the seat of the Catholic church, it’s also a cultural institution and a major museum that was welcoming nearly 7 million visitors a year before the pandemic. Unbeknownst to most of the tourists however, is the Pope’s personal botanical garden of Eden that has been maintained for over 700 years and covers more than half of the country – and only those is the know will make it into the heavenly oasis away. So let’s step away from the crowds so we can let you on in this divine secret…

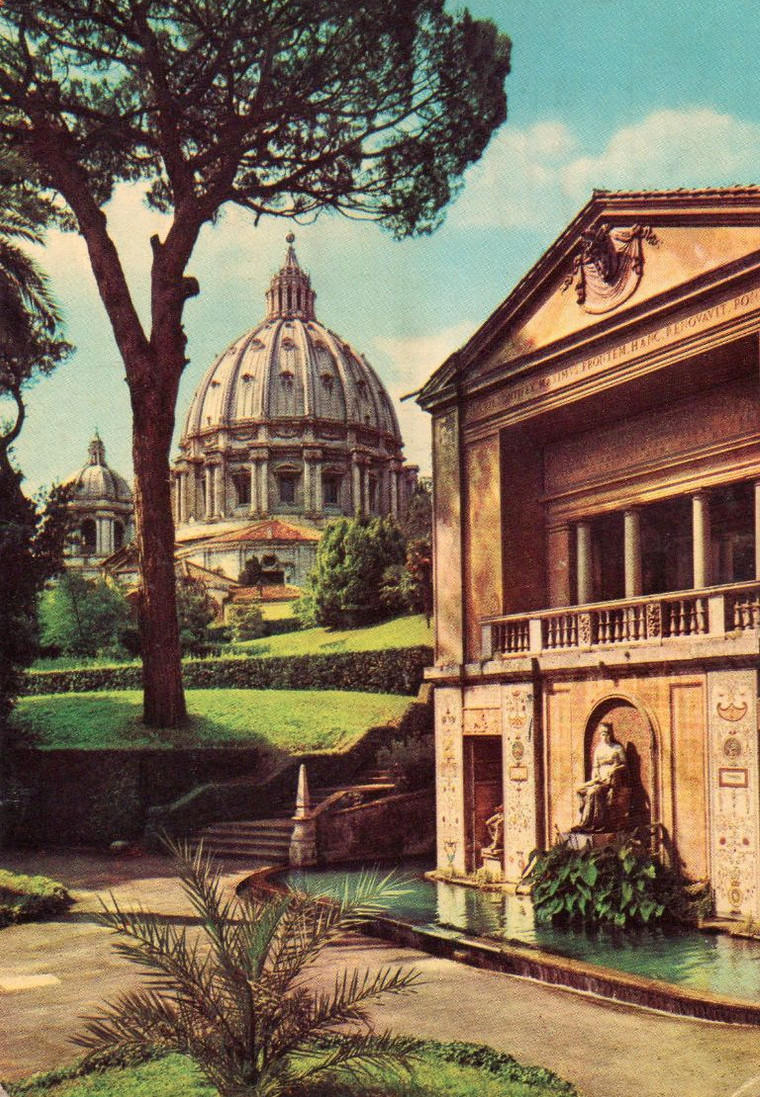

The Vatican enclave is split between buildings and gardens: the Basilica, the Sistine Chapel, other chapels, the galleries, the palaces, the courts and courtyards fill the eastern side. The gardens, occupying more than half of the hillside site spill out to the west, tumbling down to the perimeter bastioned walls. The lush and lavish gardens are peppered with gazebos, pavilions and sculpture, the most endearing and memorable being the heavenly oval-shaped piazza at the Casino of Pius IV, designed by the architect Pirro Ligorio. The gardens are also home to the Vatican’s radio station, from which it broadcasts papal news (the independent city-state also has its own newspaper).

Now a glorious Garden of Eden and essential respite for weary popes, the Vatican and its gardens were off to a rather sticky and ignominious start as a mosquito-infested marsh and the execution yard of despotic Roman emperors. It would take over 20 centuries for this sacred patch of land to be drained, seeded, germinated, grown and for it to blossom into an almost biblically impossible embodiment of perfect nature. Over the centuries this earthly paradise would serve as a refuge for popes and cardinals, artists and academics alike. Like all great gardens, its eventual flowering would be rooted in the many eons of endless patience and expert green-fingered work of nurserymen to bring it to maturity for that perfectly idyllic, golden Italian summer afternoon’s moment of divine contemplation.

Back down to earth and the ancient Roman Republic didn’t conceive of this patch of marshy ground to the west of the river Tiber as a true part of their great city. History books tell us that in the early days of the Empire, Germanic and Gaul factions of the armies had encamped on the western bank (named the Ager Vaticanus) but had suffered and died not only from the unhealthy hot, damp and mosquito-infested environment, but allegedly also from the poor grapes grown in infertile soil and the resultant bad wine.

With the expansion of both the Empire and the city of Rome, more land was required and the settlement mushroomed across the river to the west. The infamous, merciless and tyrannical emperor Nero, wanting to plant his legacy ‘monument’, allegedly arranged a fire to clear the newly built-up area for his greater stadium, an expanded long circus started by his nasty predecessor Caligula.

Nero’s arena is regarded as the crucifixion ground of Saint Peter, in 64 AD. Saint Peter was the first ‘pope’ and aptly titled ‘the Rock’, referring to him being the foundation of the Roman Catholic Church. Saint Peter’s presence commences the transformation of what was a pagan Roman swamp into a sacred Catholic garden. The first ground breaking of a Saint Peter’s Basilica or church appeared in 326, planted directly over the grave of its namesake. Not just a church, but a religious heart for the western world, this enclave grew: chapels, guesthouses, halls, stables and kitchens, all that a great spiritual site required, including a palace for Pope Symmachus by the end of the 5th century. Almost 10 centuries later, the relatively modest original piecemeal buildings of the old St Peter’s Basilica were replaced by the present-day colossal, classically-inspired domed cathedral, over which the greatest Renaissance artists and architects such as Michelangelo, Bramante and Bernini toiled.

From the moment of St Peter’s execution the ground was considered sacred and legend has it this holy ground was spread with sacred soil by the emperor Constantine, taken from Mount Calvary. The garden grew through the Dark Ages. By the late 13th Century, Pope Nicholas III decided the political climate had improved such that time was ripe for the planting of a ‘Pleasance’ for meditation and contemplation within the protective enclosure of the old Leonine walls. This pope was also intrigued by the medicinal qualities of plants and under his guidance, the first certified botanical garden in recorded history was started to explore herbal remedies and their healing properties. The succeeding pope Nicolas IV and his physician Simon of Genova developed the garden to be the first great cultivation for medicinal purposes in Europe. The gardens didn’t only supply potions and pastes, but attracted lectures, demonstrations and captured the scientific attentions of the then newly founded University of Sapienza. Not yet a completed garden of Eden, but well on its way: safe, secure and spiritual, the following centuries would prove to bear even more fruits in this fertile setting.

In pursuit of this Garden of Eden, Popes Paul IV and Pius IV employed Pirro Ligorio (1512-1583), an Italian architect, painter and landscaper to work as their papal architect. Ligorio had excelled with his spectacular villa and water garden designs at the Vila d’Este for Cardinal Ippolfo. Here the garden was an intense and immense parade of everything to do with water: cascades, waterfalls, fountains, wells, sprays, plumes, ripples, streams, ponds, baths … it was all there, l’acqua pouring down the hillside from the lofty villa terraces above. Each level, terrace and platform had a vista and an allegorical overtone. Perfect pavilions and summerhouses punctuated the crafted hillside. Villa d’Este was indeed a landscape for the gods.

Pirro Ligorio’s task was to elevate the gardens in the Vatican to that of an Eden. The centrepiece would be an exquisite, meticulously crafted grouping of summerhouses arranged around an oval courtyard. Ligorio’s keynote piece at the Villa d’Este was the ostentatious oval fountain with its gigantic overflowing bath floating above an oval pool. Ligorio would repeat the sensuous and divine oval theme in the heart of the Vatican garden, this time as a sparkling marble-inlayed courtyard with four fantastic and intricately decorated pavilions at the four poles of the oval. Originally called the Casina del Boschetto (Cottage in the Woods), Ligorio created an exquisite grouping of miniature candy carved palaces with all surfaces both inside and out lavishly encrusted with ornamental foliage, flowers and frolicking figures. The Swiss historian Jacob Burckhart would later describe it as ’the most beautiful afternoon retreat that modern architecture has created’.

Ligorio was one of three distinguished artists who was rewarded with an honourary citizenship of Rome in the 16th century, the others being Michelangelo, Titian and Guglielmo della Porta. Renaissance Italy and Rome had seen the proliferation of many intellectual ‘academies’ that started as private meetings and clubs but that would in later centuries become learned institutions. One such academy was the Notti Vaticane (or Vatican Nights), an intellectual society that congregated after dark in the Vatican gardens to discuss the arts, faith, science, spirituality and all intriguing matters of the universe under the protective canopy of this new Eden.

The Vatican garden was established and the trees would grow tall over the coming centuries. Like an Eden, the garden needed fauna as well as flora. Single animals had been introduced from time to time, a leopard in 13th century and an elephant in 1514. The 19th century would see the final act for an Eden, when Pope Leo XIII introduced a menagerie of exotic animals including gazelles and ostriches gifted to him by the Bishop of Carthage. Unfortunately, the keeping of animals didn’t last, but the garden’s cedar trees are home to a tribe of bright green parrots that have invaded the Vatican City over the last few years.

Today, the gardens, Rome’s least crowded tourist attraction, are a secluded and semi-private realm, protected by their complete enclosed circuit of walls, libraries and churches. They can only be visited as part of a guided visit run by the Vatican, which also includes a skip-the-lines entrance to the Vatican Museums and Sistine Chapel. The planting is divided into three distinct styles: an informal English garden of trees and winding paths, a French section of rigid boulevards and allées and an Italian labyrinth of perfectly-cut hedges and wispy cypresses. The vestiges of Pope Nicolas III’s 13th century botanic plantings can still be seen if you know what to look for, while Pirro Ligori’s magnificent oval summerhouse still has pride of place in the heart of this sacred spiritual garden.