In 1912, Aida Overton Walker stood at the top of the stairs at the Victoria Theater about to make her entrance as the titular role in the play Salomé. By then, the Salomé craze was mostly over, but the role still had plenty of allure. At a time when women had few rights and little power – and when leading roles were mostly virginal damsels in distress – the Biblical temptress provided an exotic guise that gave actresses the license to be dangerous, sexy, commanding. Every actress worth her salt had given Salomé a whirl and Walker had done so herself three years previously, but never before at a predominantly white theater in New York…

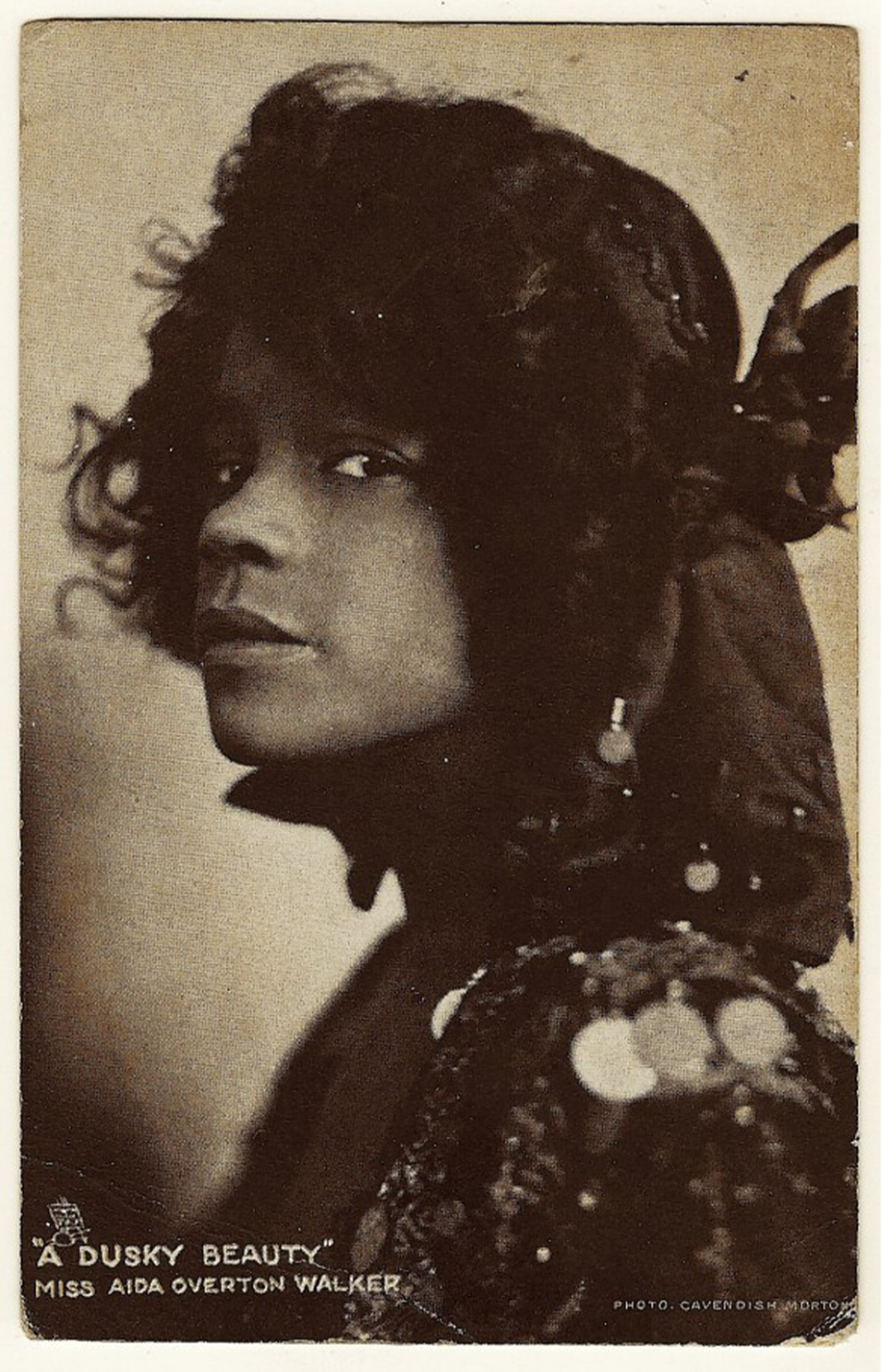

Aida Overton Walker, the most famous Black vaudeville soubrette, had co-starred in the first all-Black Broadway musical, danced before royalty, and performed in drag to critical acclaim. Now she was about to headline one of New York’s most prominent vaudeville houses – not as a maid or a saucy high yella gal or a tragic Octoroon – but as a powerful seductress who could demand a saint’s head in return for a glimpse of her body.

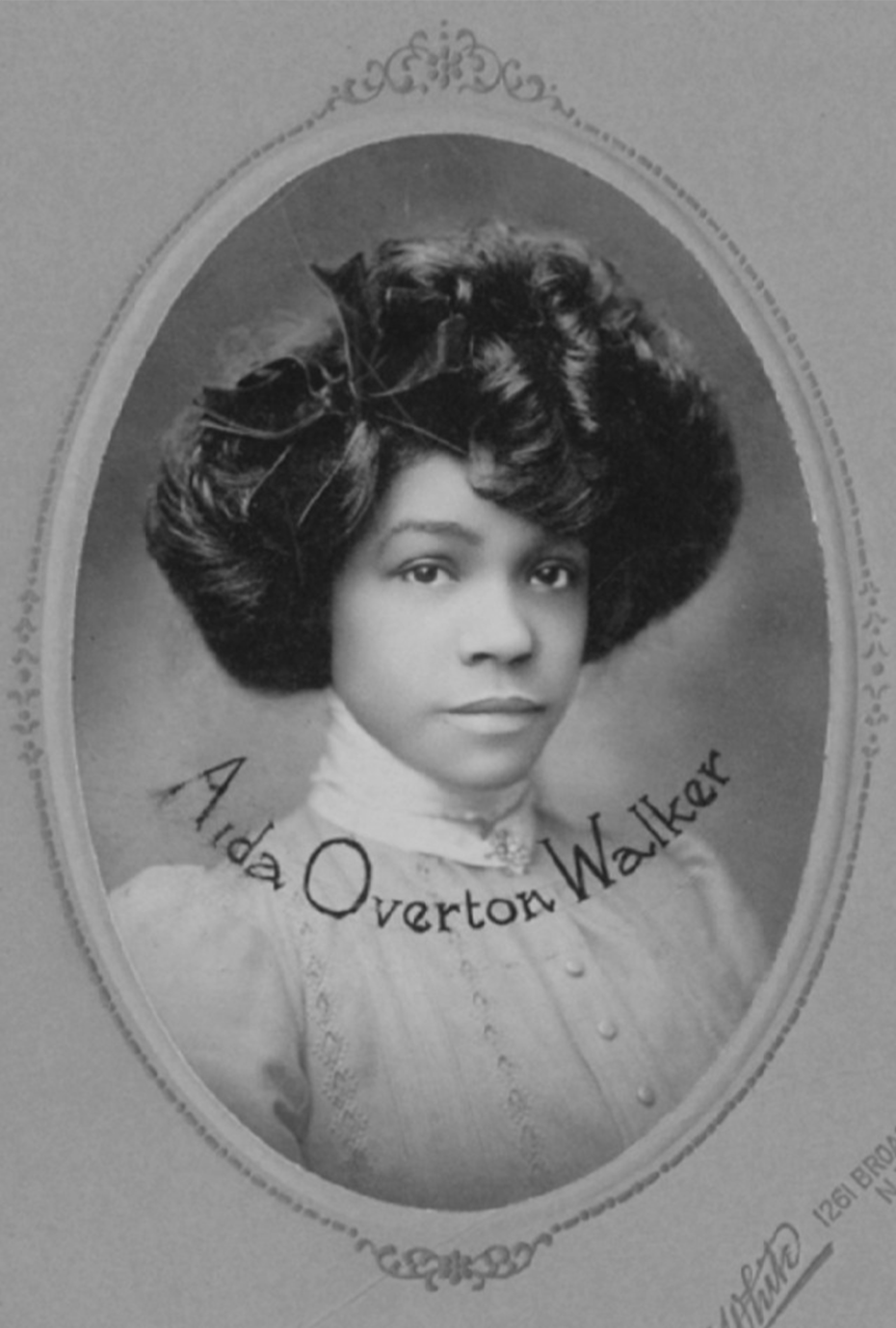

Born on Valentine’s Day 1880 in New York City, Ada Overton started performing professionally as a teenager. In 1896, she was listed in the chorus of Black Patti’s Troubadours, an all-Black show led by concert singer Madame Sissieretta Jones, called “The Black Patti” after Adelina Patti, the most famous soprano of the time. Overton appeared in two numbers in the first act, a comedic song about playing the lottery and a cakewalk.

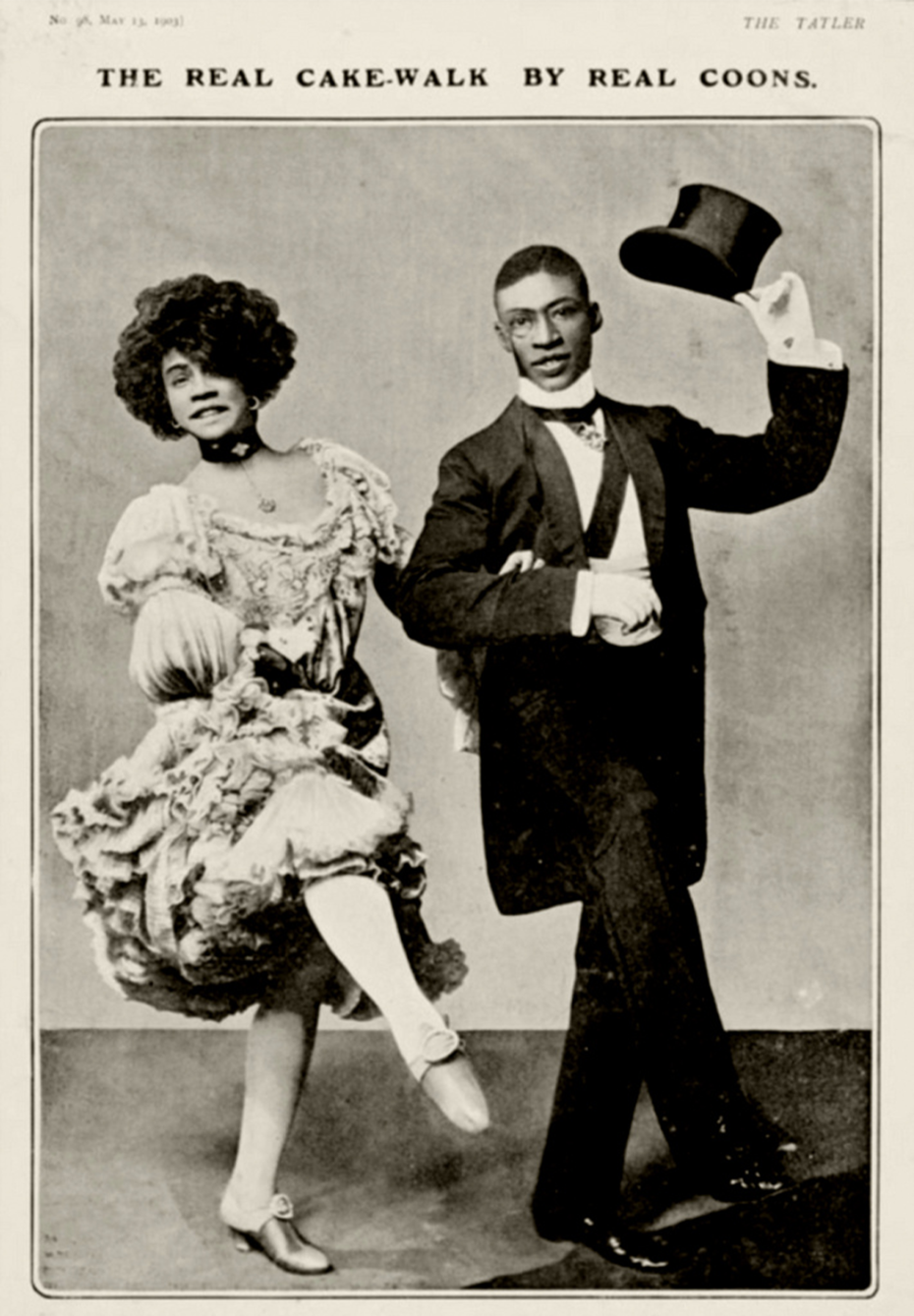

The cakewalk was the first American-born popular dance. Originating on plantations in the 1840s, the cakewalk started with slaves satirizing the cotillons and formal European dances of their masters. Throwing their shoulders back and tilting their heads haughtily, they linked arms and promenaded side by side down a chalk-line. Soon, it became a contest. Whoever could comport themselves most gracefully and pivot with the greatest ease at the end of the chalk-line would win a cake.

After the Civil War, Philadelphia’s Centennial Exposition of 1876 featured a romanticized recreation of antebellum plantation life that included a cakewalk contest. White minstrel performers in blackface were inspired and began reproducing the cakewalk onstage. The cakewalk seemed to fulfill a post-Reconstruction zeitgeist and soon everyone was high-stepping in formation, including Black people, who were echoing White people satirizing Black people satirizing White people. The Grand Cakewalk was held at Madison Square Garden in 1892 and cakewalk contests popped up all over the country. Not long afterwards, the cakewalk was exported to London and Paris.

The Black community had mixed feelings about the cakewalk. It reached backwards to slave days and perpetuated racist tropes, but the popularity of the dance also gave Black performers opportunities that they never had. A decade after the slim gains of the Reconstruction era, Black singers and dancers were finally able to infiltrate white theaters, but they were forced to inhabit racist stereotypes. “Nothing seemed more absurd,” Aida’s husband George Walker later said, “than to see a colored man making himself ridiculous in order to portray himself.”

Aida and George Walker met in 1898 when her Troubadours friend Stella Wiley invited her to pose as one of four cakewalk dancers for an American Tobacco Company trade-card. At the photo shoot, they were coupled with George Walker and Bert Williams, new to New York and about to hit the big time.

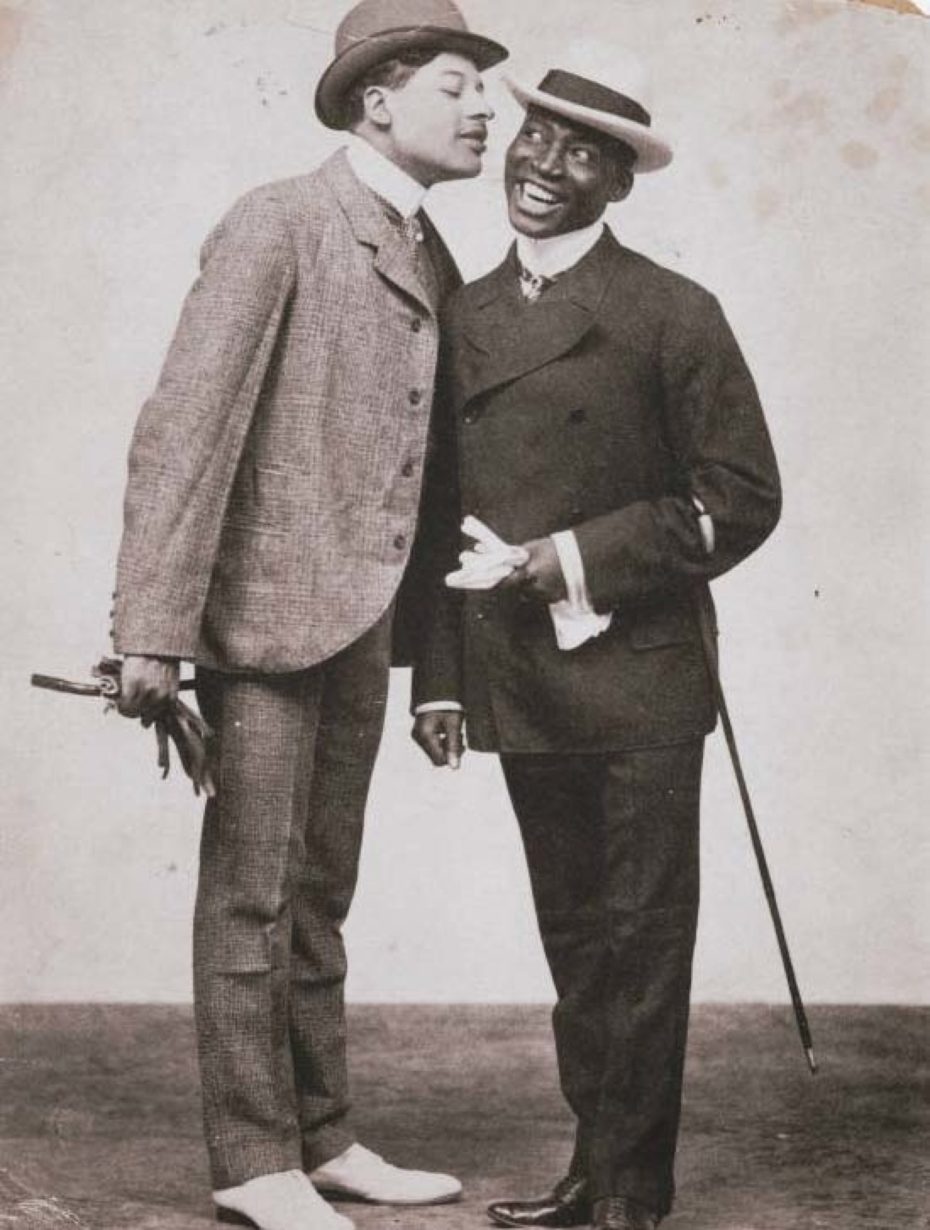

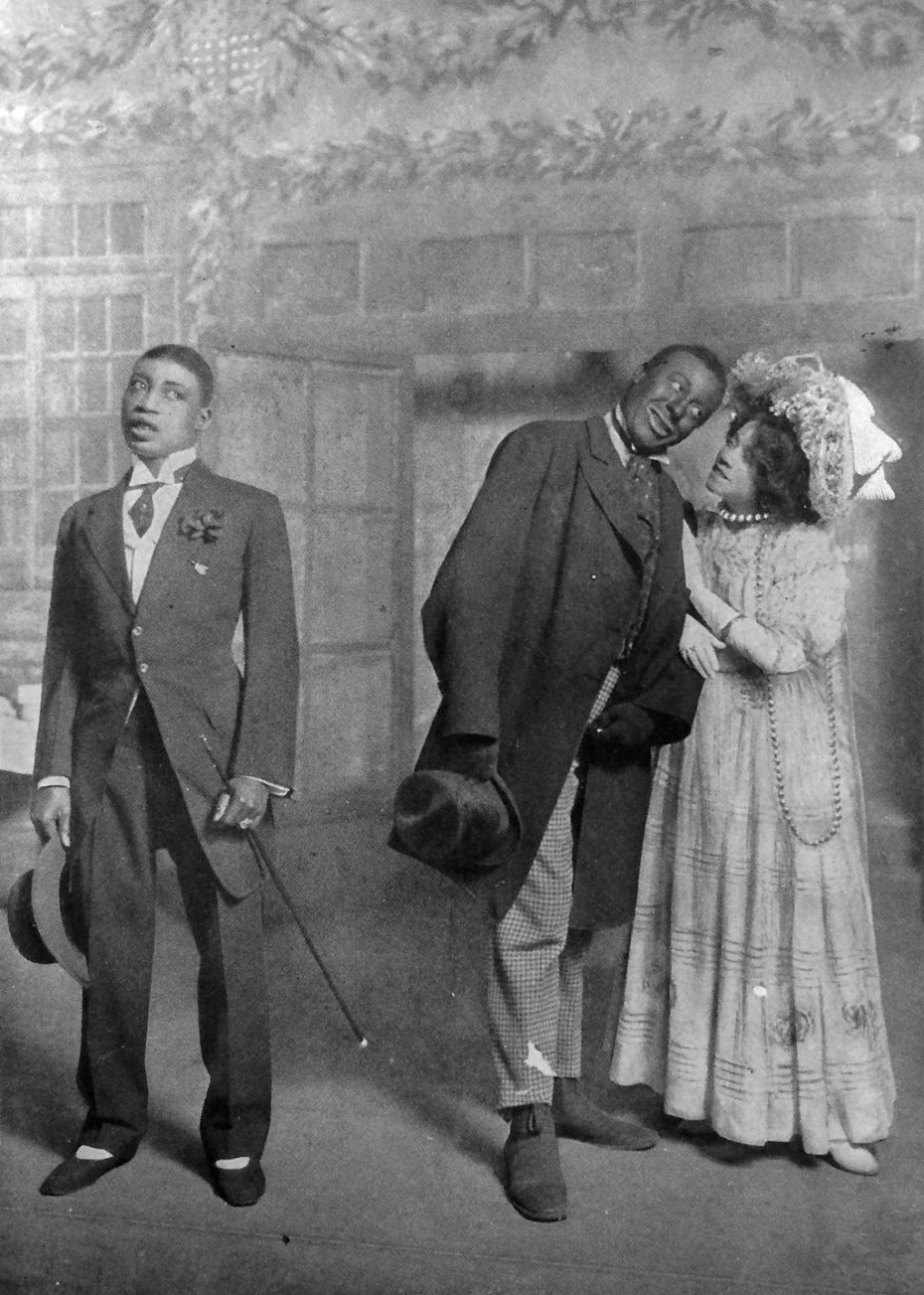

Like all great comedic duos, Walker and Williams were opposites. George Walker was a small, dark-skinned, sharply-dressed, flashy lady killer. His partner Bert Williams was tall, light-skinned and introspective. They teamed up in San Francisco and struggled to make it in vaudeville until Williams finally gave in to blackface. To his surprise, the grotesque mask of burnt cork freed him from his inhibitions and released his genius for finding comedy in pathos. Williams became a star playing a bumbling, sad sack, pessimistic, everyman dubious of the wild schemes concocted by the fast-talking, ever-optimistic Walker.

By the time they hit New York, they were calling themselves “The Two Real Coons,” archly suggesting that two Black men might be better at portraying themselves than all those white impersonators. Aida Overton became their leading lady, their creative director, and the primary choreographer for their revues. She and George Walker married within a year.

Weeks after their meeting, the three were on tour in Senegambian Carnival. It was an expansion of William Marion Cook’s Clorindy, or the Origins of the Cakewalk, the first all-Black ragtime musical, which had played to enthusiastic audiences all summer on the roof garden of the Casino Theater. Williams and Walker played the lead roles, while Overton Walker choreographed the show and led a chorus of dancers.

Senegambian Carnival was followed by a string of other musicals with much of the same all-Black team. Cook wrote the music, Jesse A. Shipp wrote the book, Walker and Williams starred, Overton Walker choreographed and played the leading lady. The success of The Policy Players (1899) and Sons of Ham (1900) proved that Black musical comedies could be viable enterprises, even as they moved slowly away from minstrelsy. Additionally, all of Overton Walker’s hit musical numbers – I Don’t Want No Cheap Man, I Want to Be a Leading Lady, and Miss Hannah from Savannah – were defiant proclamations of self-reliance and self-worth. This was one Black woman who wouldn’t sweep your floors or make you hotcakes.

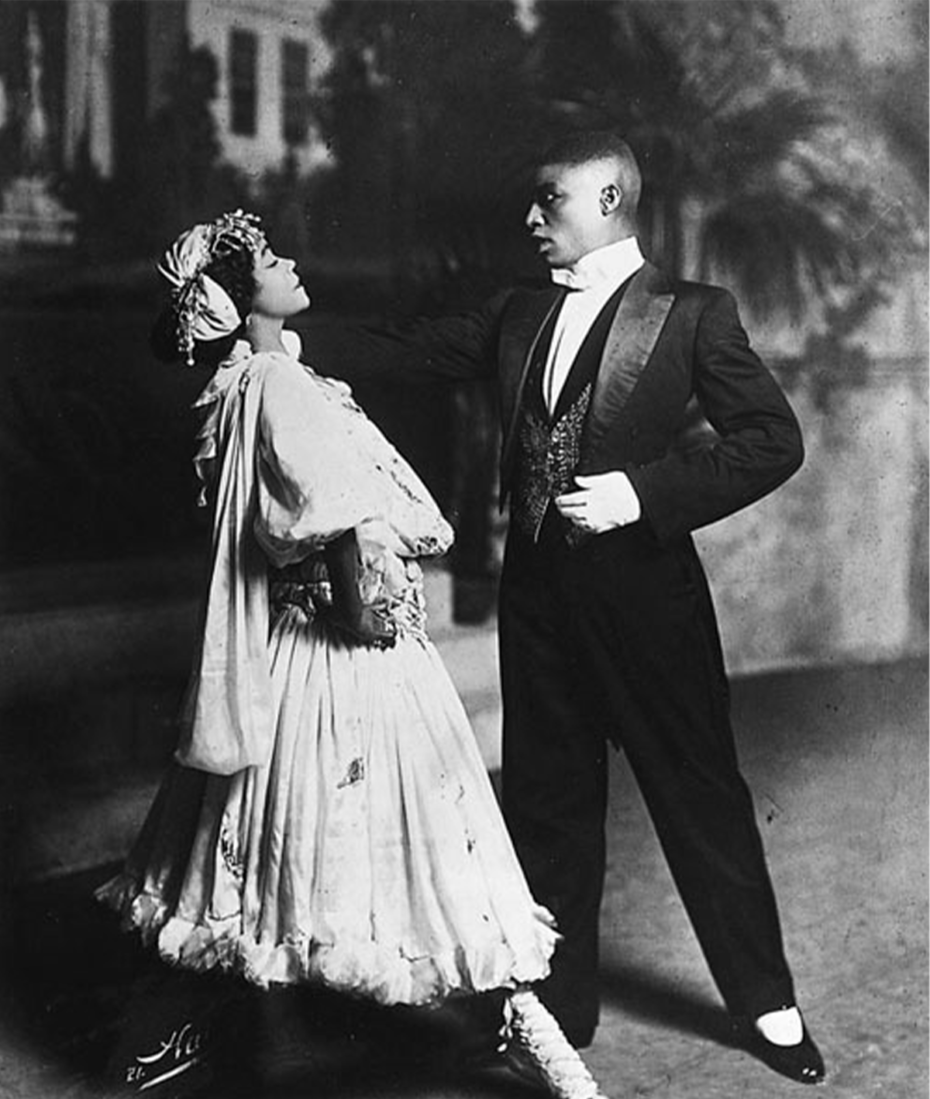

Through these productions, Overton Walker came to be known as the Queen of the Cakewalk. Anyone who ever saw her dance never forgot it. The writer and photographer Carl van Vechten, who saw Ada and George Walker cakewalk in Chicago in 1900, called the performance “one of the great memories of the theatre,” remembering “the line, the grace, the assured ecstasy of these dancers, who bend over backward until their heads almost touch the floor, a feat demanding an incredible amount of strength, their enthusiastic prancing, almost in slow motion, have never been equaled in this particular revel, let alone surpassed.”

In 1903, the Williams and Walker Company scored their greatest triumph with In Dahomey, the first musical written, composed, and performed by African-Americans at a major Broadway house. There were those who worried that an all-Black show on Broadway would trigger a race riot, but In Dahomey played to appreciative audiences of all colors, although Black audiences were confined to the upper balconies. The show was a smash hit, featuring Williams and Walker as two Boston detectives in search of missing treasure in Benin (then called Dahomey). Aida choreographed the show and played Rosetta Lightfoot, “a troublesome young thing.”

In Dahomey was so successful in New York, the entire production was transferred to the Shaftsbury Theatre in London. At first, it received only moderate attention, but then came a royal command for an afternoon lawn-party performance at Buckingham Palace to celebrate the ninth birthday of the Prince of Wales. Aida sang and performed a solo dance on a parquet floor that had been laid on the grass and received a diamond brooch from Edward VII.

The cakewalk was not in the Broadway production of In Dahomey, but audiences in London expected to see it. They also expected the women to be wearing “plantation feathers” and were surprised that Overton Walker had clothed them in the latest Parisian fashion. After the royal family asked George and Aida Walker to demonstrate the cakewalk, they decided to add a grand cakewalk finale to In Dahomey, which became the hit of the show. Soon, Overton Walker was teaching British high society how to cakewalk. Between royal patronage and cakewalk fever, the show was held over in London and then toured England and Scotland. In Dahomey returned to Broadway with the new cakewalk finale and then traveled the United States for two years. By the end of the run, Bert Williams, George Walker, and Aida Overton Walker were household names.

Their next show Abyssinia (1906) continued the Back to Africa theme, reminding Black Americans during a time of lynchings and open racism that they had come from greatness. Abyssinia was a lavish production with a huge cast of Black performers and live camels. It was another smash hit, with Williams debuting “Nobody,” the signature song that he became associated with for the rest of his life.

Abyssinia was followed by Bandanna Land (1908), in which a pair of real estate scammers build a Black amusement park called Bandanna Land. Overton Walker sang two songs and presided over a ragtime parody of The Merry Widow. After four months on Broadway, Bandanna Land went on tour, continually refreshing itself along the way. Overton Walker added a song, A Sheath Gown in Darktown, appearing with a chorus of un-corseted women in the latest style from Paris. In the last months of 1908, Bandanna Land began including a special feature – “Aida Overton Walker in The Vision of Salomé.” Possibly to mitigate white anxiety over a Black woman performing a serious artistic dance, Bert Williams went on afterwards as a burlesque Salomé, in which John the Baptist’s head was replaced by a watermelon.

While Bandanna Land was in Chicago, the company began noticing that George Walker was slurring his words and couldn’t remember his lines. At the next stop in Dayton, Ohio, it was clear that something was very wrong. Walker was forced to drop out of the show to seek treatment. It turned out that he was in the last stages of syphilis, which was incurable at the time. He never recovered and died in 1911 at the age of 38. Rather than cancel the remainder of their engagement, Overton Walker performed in drag as her husband. Wearing his flashy clothes and doing his famous cakewalk strut, she sang his hit song Bon Bon Buddy to great acclaim.

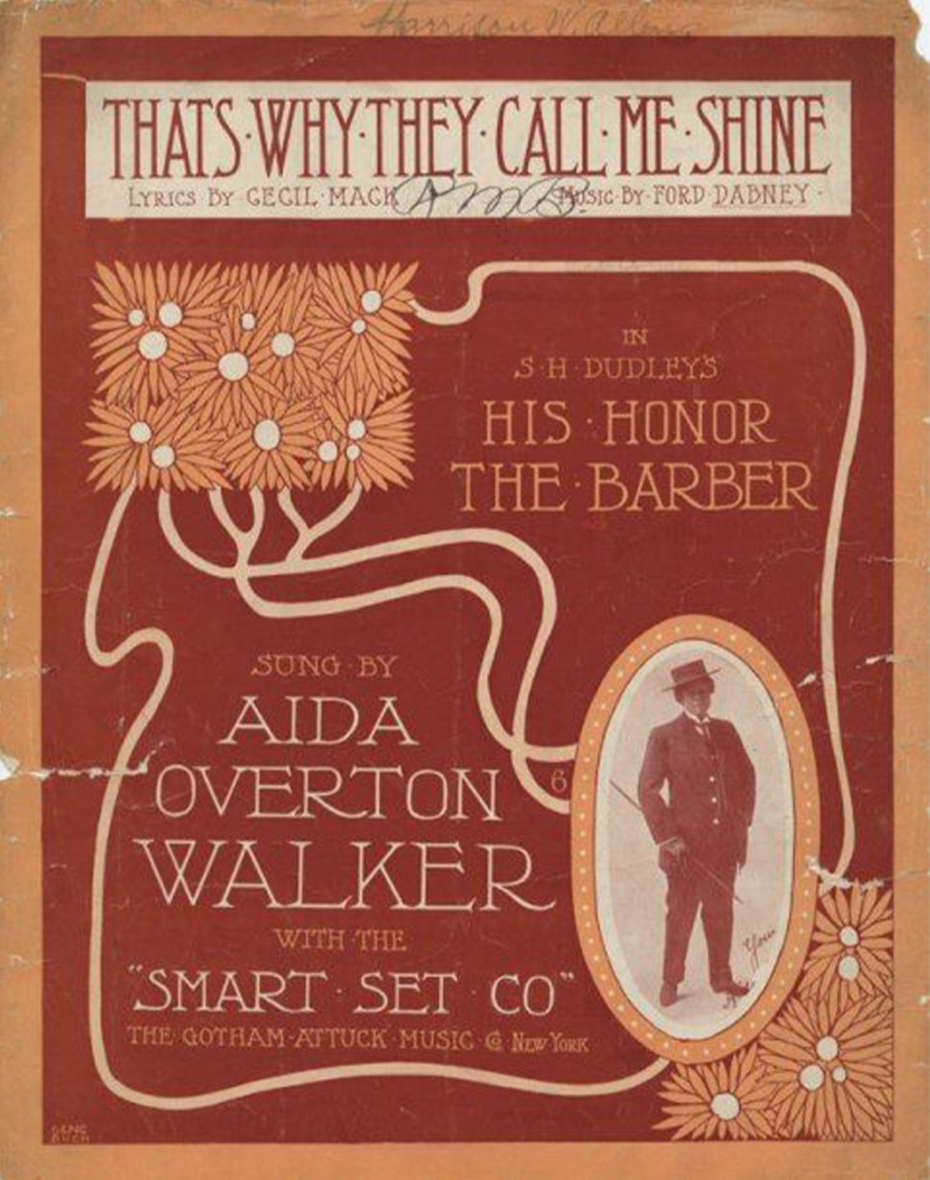

With Walker gone, both Bert Williams and Aida were on their own. Many thought they should team up and create a new Walker and Williams, but Aida demurred. After a year at loose ends, Williams accepted an unprecedented offer from Flo Ziegfeld to star in the Ziegfeld Follies. Aida went on to perform on Broadway in Bob Cole and J. Rosamund Johnson’s The Red Moon and then toured in His Honor: the Barber. In both these productions, she was acclaimed for performing in male drag, channeling her late husband.

For several weeks in 1912, producer William Hammerstein made a big secret out of who was going to play Salomé at the Victoria Theater. Speculation centered a number of white dancers including Ruth St. Denis and Isadora Duncan. When it was finally announced that the seven veils would be donned by Aida Overton Walker, theatergoers reacted with pleasant surprise.

Overton Walker had to walk a fine line as Salomé. In addition to being tasked with racial uplift, she was scrutinized for her respectability as a woman. In 1905, she felt obliged to state in The Colored American Magazine, “I am aware of the fact that many well-meaning people dislike stage life, especially our women. On this point, I would say, a woman does not lose her dignity today – as used to be the case – when she enters stage life.”

Through Salomé, Overton Walker challenged how Black women were viewed and demanded to be recognized as an artist of the same caliber as Maud Allen, Gertrude Hoffman, and La Sylphe. The production featured lavish scenery, a 36-piece symphony orchestra, and music by acclaimed Black bandleader and composer James Reece Europe. Subverting audience expectations, Overton Walker’s Salomé received praised for its modesty and artistry rather than its eroticism. Even so, Variety proclaimed, “It was some Salomé boys, and catch it while it’s going.”

By this time, Overton Walker had started two vaudeville troupes to mentor young Black women, the Porto Rico Girls and Happy Girls. In 1913, she directed and choreographed several shows for these troupes that were performed throughout the United States. She was acclaimed for donning male drag during these shows, playing the jaunty dandy surrounded by women. Seeing the end of the cakewalk fad, she expanded her dance repertoire to include tango and rumba. She also reunited with Bert Williams for an all-star gala to benefit The Frogs, a union for Black performers founded by her late husband.

Then in 1914, all of this creative fire was suddenly extinguished. After just two weeks of illness, Overton Walker died of kidney failure. Her death was reported on the front page of the New York Age, which lamented, “No colored woman was better known or had a more brilliant number of accomplishments in her particular sphere, and her death came as a tremendous shock.” Hundreds of people came to her home in hopes that the report of her death was untrue. She was just 34 years old.

About the Contributor