One of the most popular questions in ethics is what would happen in a real Lord of the Flies in which a group of children were left to fend for themselves. In 2007, one reality TV show decided to find out, letting 40 kids loose on a movie ranch set with no adult supervision — what could go wrong? Well just about everything. The irresistible disaster that was CBS’s “Kid Nation” only lasted one season, but 15 years later, it remains a cautionary tale for the real world consequences of reality TV.

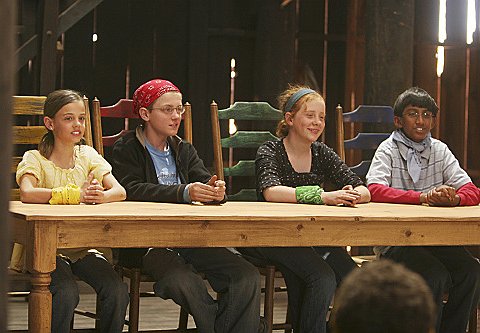

The idea behind “Kid Nation” was to see if children could create a functioning society from scratch, setting up economic, governmental and social systems on their own. There were no adults present, except for film staff and child psychologists waiting in the wings. The show was filmed on location at the Bonanza Creek Movie Ranch, a privately owned town built on the ruins of Bonanza City, New Mexico – the very same western set where Alec Baldwin fatally shot the cinematographer Halyna Hutchins with a prop gun in 2021. The co-ed participants (ages 8 to 15) were taken out of school, not allowed to contact their parents and had to do all the physical labor to keep the town running. During periodical “town meetings,” the kids met and could choose to stay or leave. Each episode, a Gold Star (valued at $20,000) was awarded by the elected Town Council to an outstanding participant.

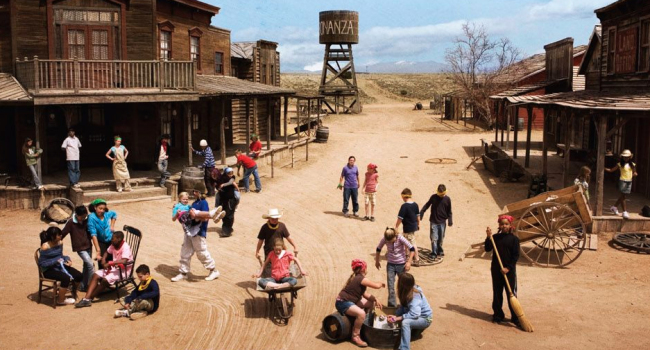

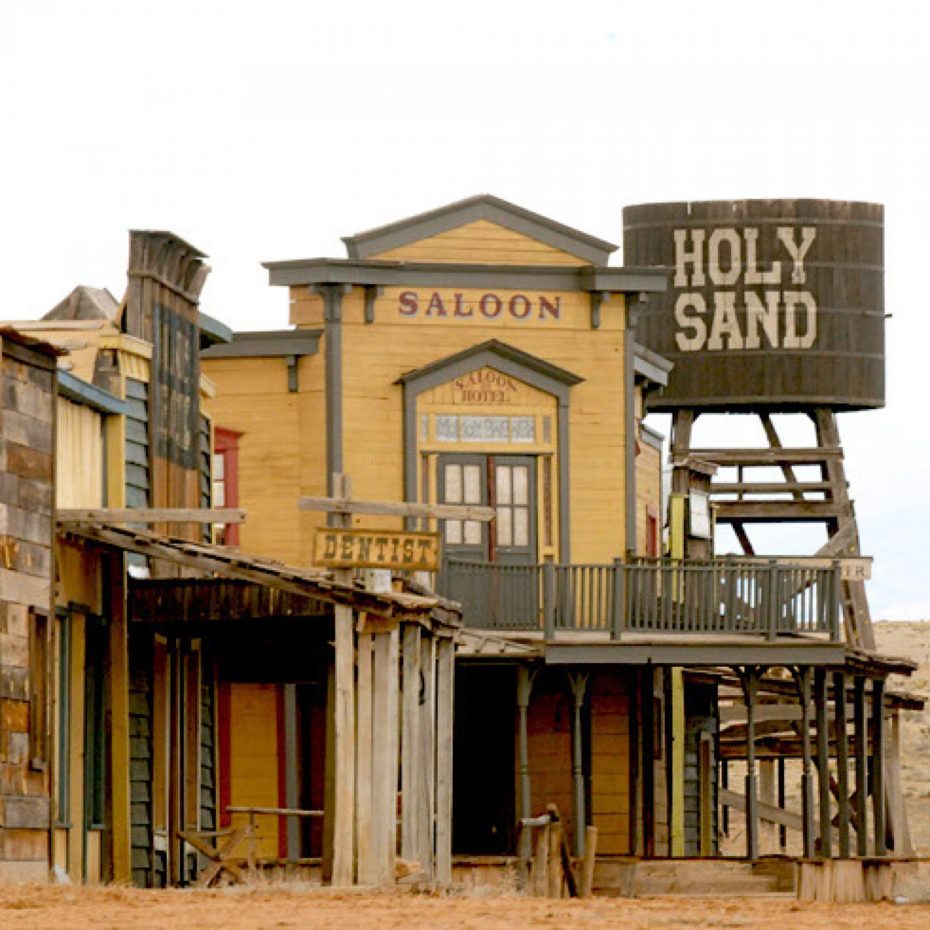

“Kid Nation” began with the kids being taken on a school bus to the middle of nowhere to meet the host Jonathan Karsh. Participants ranged from wanna-be child stars to kids who grew up on farms and had experience with a more rustic lifestyle. Their resilience was tested from the beginning as they were tasked with carrying all their supplies on wagons a few miles to the town of Bonanza. There, the “pioneers” found houses to bunk in, a canteen and multiple shops including a candy emporium, dry goods store and saloon (just serving soda, of course). Early on, the show divided the participants into four groups, and each episode they competed in various challenges to place at a certain level on Bonanza’s economic ladder.

The “upper class” that got paid the most had no job duties while the “laborers”, who got paid the least, were in charge of cleaning up after everyone. In the middle were cooks and merchants who manned the businesses. Unsurprisingly, this created tension amongst the groups, which the producers clearly played up in reality TV fashion. A diary “tasked” the Town Council in methods to facilitate a successful community. This included killing their chickens in order to have a protein source (the animal lovers locked themselves in the coop to protest) and holding an interfaith religious service to bring everyone together (of course no one actually attended).

What’s surprising though is how well the children were able to function without adults; many of the older members served as de facto leaders, helping the younger members when they felt homesick or struggled with their work. Every town meeting, they also had the opportunity to hold their Town Council accountable by deciding to elect new members if they felt misrepresented. during weekly challenges — usually some sort of physical activity or scavenger hunt — the Town Council was given the option of accepting a practical prize like a microwave, multiple outhouses (as the show started with only one) and toothbrushes and toothpaste, or a fun prize like a television, barbecue or pizzas. Almost every time, they chose the more practical option. In the last episode, the sign laying out specific job roles was destroyed by producers, leading the children to riot, stealing all the goods from the stores and leaving a mess. But the next day, they woke up and realized that even without enforced professional roles, they benefitted from a functioning society and spent the day cleaning.

While this might have proved that a “kid nation” could exist, the fact that the show deprived participants of these necessary resources (like enough bathrooms and hygiene products) raises the question of how ethical it was. The $20,000 weekly prize also hung over the heads of many, encouraging them to stay on the show (and put in the work to impress the Town Council). One kid who won even said he was happy to now have the money to pay for college. After it wrapped, the show was formally investigated for child abuse, neglect and exploitation. One child got sick after accidentally drinking bleach and another had burnt themselves while cooking, explained Jimmy Flynn, who was the first contestant to leave, in a 2020 interview.

“I was expecting it to be more like an adventure,” said Flynn, who was one of the youngest participants at 8 years old. “I thought it was going to be fun. No parents. Let’s drink root beer until midnight and no one can tell us our bedtime kind of thing. It will be great. And I got there and it was horrible.”

Others look back more positively. Laurel McGoff, who was a Town Council member, told the A.V. Club that “My experience on the show was the ultimate best experience of my life. It was really the most memorable part of my childhood.”

Anjay Ajodha, another Town Council member interviewed by the A.V. Club, fell somewhere in the middle: “We weren’t abused. We weren’t hurt in any way. But it was definitely a lot more exploitative than I remember it being back then. The thing is, we weren’t fully formed people. We were kids.”

It was this controversy (including a call to boycott “Kid Nation”) combined with a slew of negative reviews that led the show to be canceled. But in recent years, it’s experienced a revival online. Many contests have used YouTube as well as other platforms like TikTok to reflect on their experience as adults. While kid-centered reality TV has switched focus to highly talented young chefs and fashion designers, “Kid Nation” proves that as hard these shows try to mimic reality, they are heavily constructed, often to the detriment of those involved. We will never really know if a kid nation could be successful, and that’s probably a good thing.

In a 2014 Reddit AMA, participant Michael Thot — who said he was typecast as a “long-haired-hippie-kid-from-the-NW” — wrote that “the people that cast these shows, and the cast members themselves, are exploiting specific imagery and archetypes. In this manner, I think that reality TV says an enormous amount about what we want to look like, and how we want other people to act for our entertainment.”