Here’s the myth: alcoholic brooding genius Jackson Pollock assesses a virgin canvas as it lays prone on the ground. Then he flings, hurls, splashes, and drips paint all over it, creating a vigorous new language of art – the drip technique. Life Magazine swooned, “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” The real story? Pollack’s first drip painting, Full Fathom Five, was completed in 1947. Four years earlier a Ukrainian housewife with no formal art training stunned the art world with her all-over drip paintings and primitivist surreal dreamscapes. Her name was Janet Sobel and her art career spanned just three years from 1943 to 1946. As she faded into obscurity, Pollock rose to fame, credited for the technique that she pioneered.

Sobel was born Jennie Olechovsky in 1893 in Ekaterinoslav, an industrial city in eastern Ukraine. In the wake of the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, Jews were blamed for Russia’s bitter defeat. Sobel’s father was murdered in the ensuing pogrom. Her mother took the rest of the family and fled Eastern Europe. They arrived on Ellis Island in 1908, where a clerk changed the family surname to Wilson. Jennie decided to call herself Janet.

Two years later, at the age of 16, she married Max Sobel, who had trained as an engraver in the Ukraine. For the next three decades, as Max struggled to establish a costume jewelry business, she raised five children in the Russian-Jewish enclave of Brighton Beach. During the Depression, they were so poor, she made potato knishes for her eldest children to sell on the boardwalk.

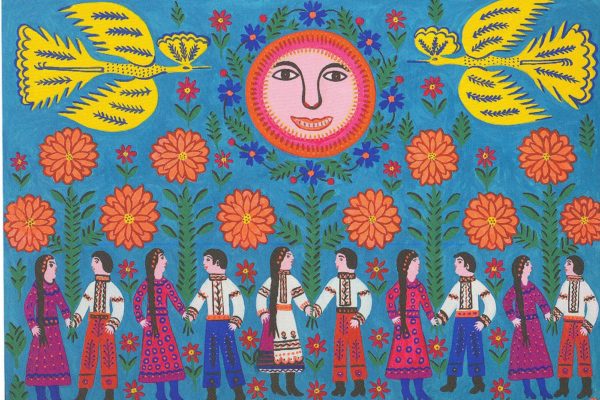

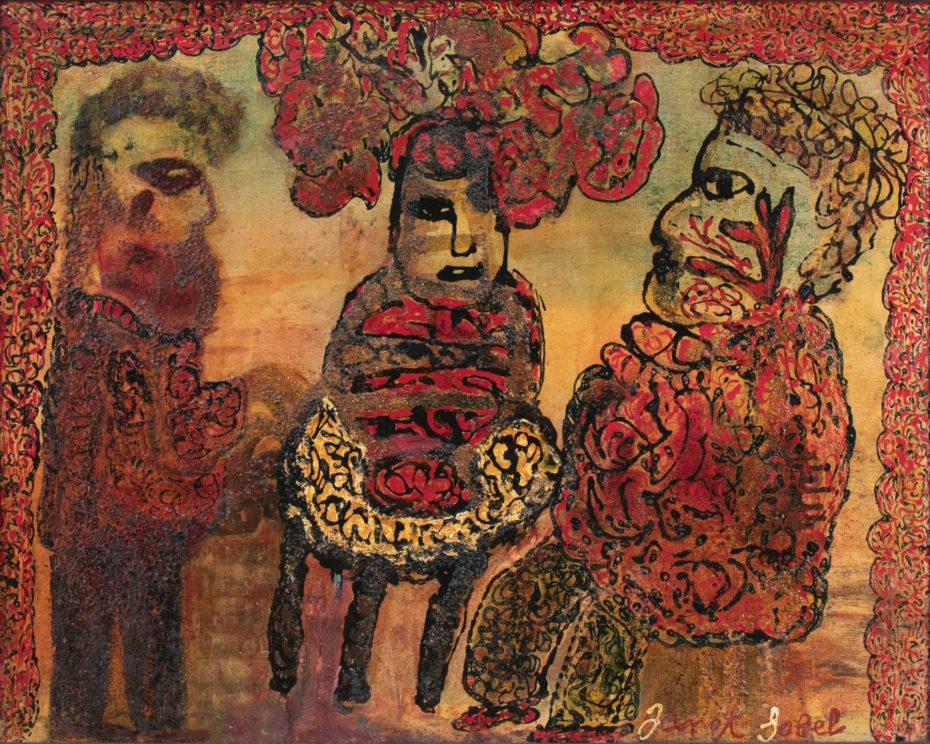

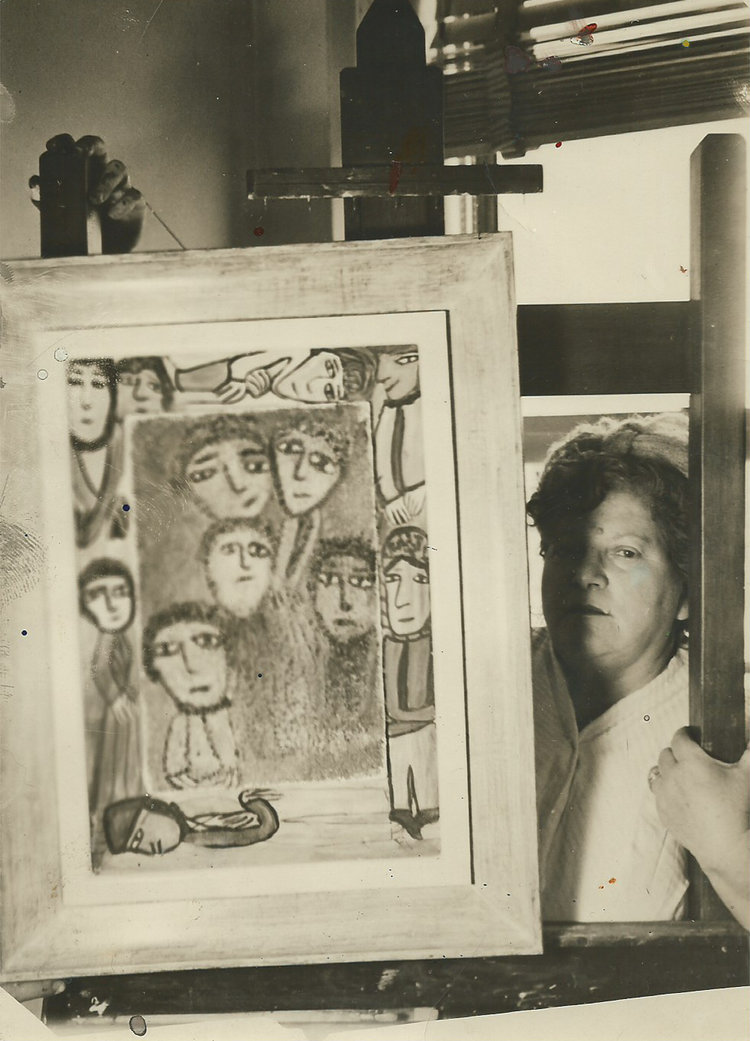

Sobel began experimenting with art in 1937 after her 19-year old son Sol took up painting. Picking up his unattended brushes and paints, she began covering discarded envelopes, cardboard boxes, and the margins of magazine pages with dreamlike, floating faces emerging from a tangle of leaves and flowers that recall Ukrainian folk art.

Impressed, Sol became his mother’s biggest champion. He reached out to prominent surrealist André Breton and fellow Russian-Jewish artist Marc Chagall. He wrote to influential gallerist Sidney Janis, who was known for championing “primitive” and “outsider” art. Five years after she began painting, Sobel was attracting major attention. Janis sold her first painting in 1942 and included her work in an exhibit at the Arts Club of Chicago. This was quickly followed by an exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum.

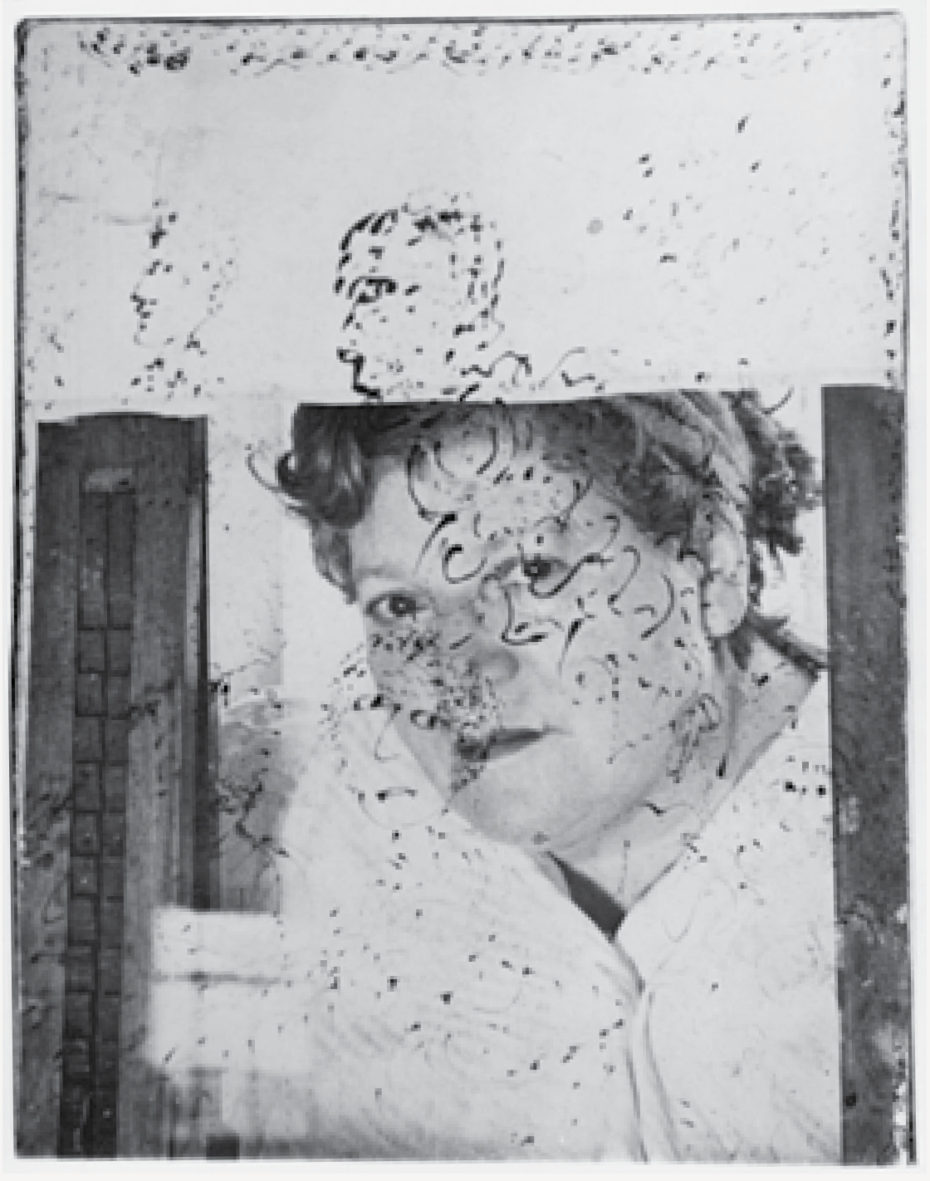

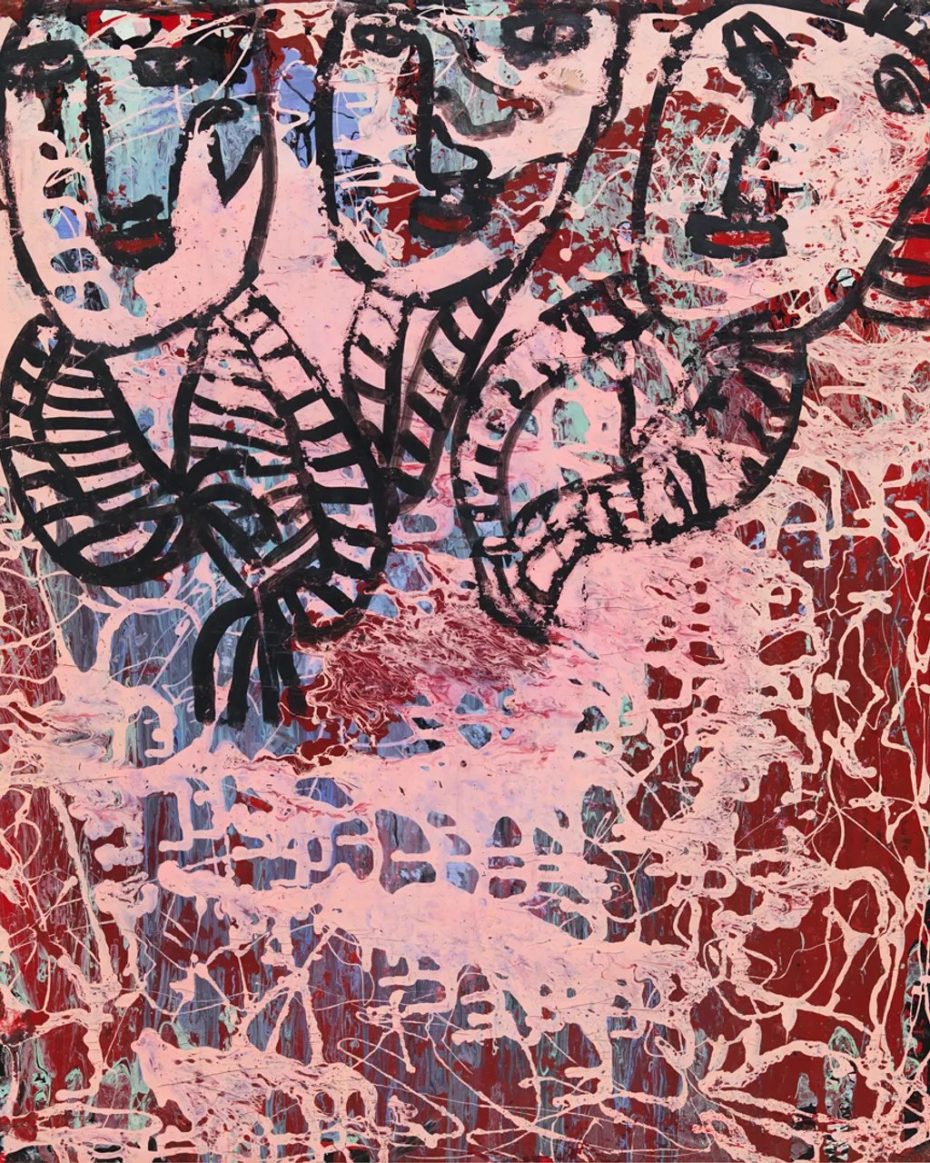

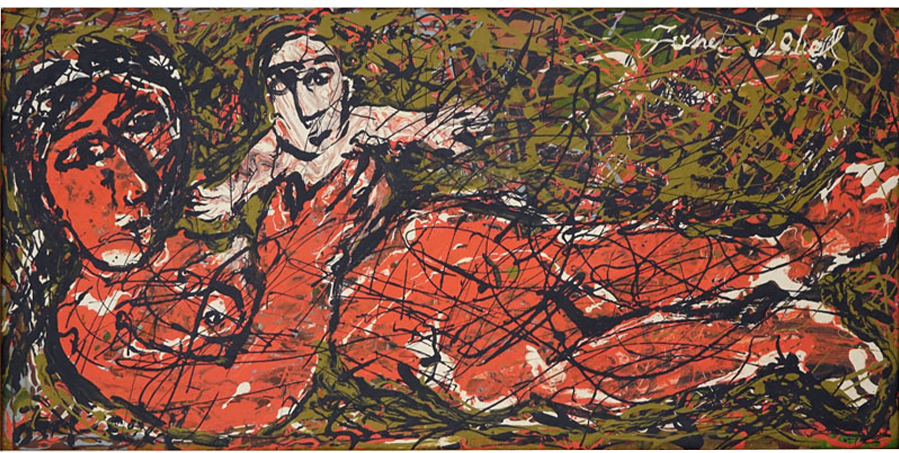

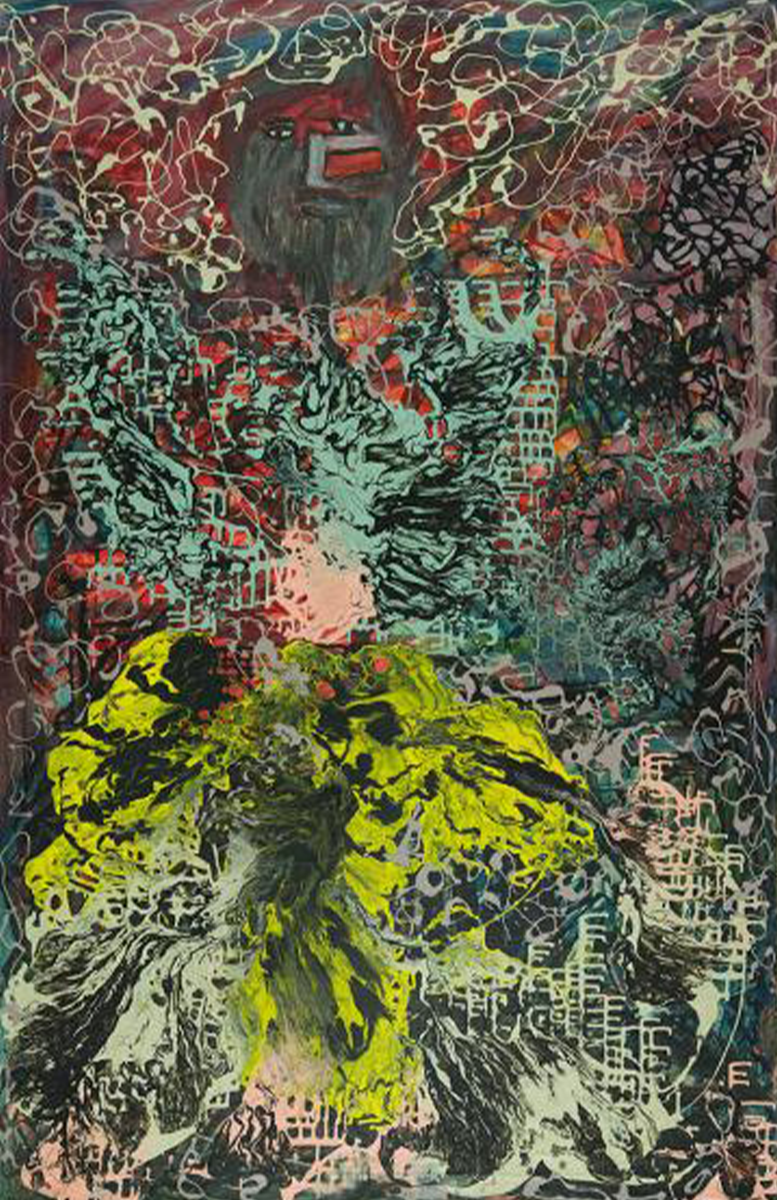

By 1944, Sobel’s art had evolved from folkloric to figurative-abstract. Then she began making bold all-abstract paintscapes. Working with the canvas on the ground, she seized implements laying around her house and improvised new ways of laying color on canvas. A vacuum cleaner was used to blow paint into whorls. Sand from the beach was added to create texture. Sobel even borrowed from her husband’s jewelry making supplies – a glass pipette became the means to drip glossy enamel paint into delicate spidery patterns. “I’m a surrealist,” she declared, “I paint what I feel.”

In 1944, Sobel was part of an art show at the Norlyst Gallery. This upstart new space was run by artist Eleanor Lust and her boyfriend, Jimmy Ernst, who happened to be the son of renowned surrealist Max Ernst, then married to Peggy Guggenheim. Presumably, this is how Sobel ended up in The Women, Guggenheim’s legendary all-women art exhibition of 1945.

The next year, Guggenheim singled out Sobel for a solo show at the Art of the Century gallery. The exhibition catalogue featured an essay by her art curator supporter Sidney Janis, who extolled Sobel for her “self-invented methods for applying pigment.” Janis predicted, “Janet Sobel probably will be eventually known as the most important surrealist painter in this country.”

But just as quickly as Sobel appeared in the art world, she suddenly vanished.

In 1946, her husband decided to move the family to Plainsfield, New Jersey to be closer to his factory. Unable to drive, Sobel was cut off from the artists and galleries of New York City. The following year, she lost her most important patron when Peggy Guggenheim closed the Art of the Century gallery and relocated to Europe. In addition, Sobel developed a mysterious allergy to something in the paint.

Her granddaughter, Ashley Shapiro, wryly surmised, “My grandmother…was squashed by the way men thought about women and the way she thought of her duties as a woman.… People thought she had allergies to paint… She had allergies to suburbia.”

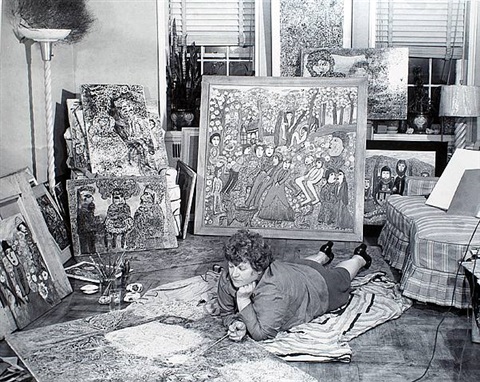

Sobel continued to create art, but after 1946, her work never hung in another gallery in her lifetime. She eventually took over her husband’s jewelry business and was largely forgotten by the art world.

Then in 1955, Jackson Pollock’s friend, the prominent art critic Clement Greenberg, confessed in his influential essay American-Type Painting:

Back in 1944…he [Jackson Pollock] had noticed one or two curious paintings shown at Peggy Guggenheim’s by a primitive painter Janet Sobel (who was, and still is, a housewife living in Brooklyn). Pollock (and I myself) admired these pictures rather furtively… it was the first really all-over one that I had ever seen… Later Pollock admitted that these pictures had made an impression on him.

Mention of Sobel’s influence on Pollock should’ve restored her name, but the compliment was so backhanded that she remained a footnote. However, in 1968, when the Museum of Modern Art was mounting a Jackson Pollock retrospective, they paid homage to Sobel’s innovation by acquiring one of her best drip paintings, Milky Way, and an untitled piece that was another remarkable example of her drip technique. Sobel passed later that year, never seeing the paintings exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in 1970.

Since then, Sobel has slowly regained some of her former prominence. Many publications now acknowledge her as the pioneer of the drip technique. The hundreds of paintings she left behind are now included in landmark exhibits, most recently Women in Abstraction, a 2021 exhibit that traveled from Le Centre Pompidou to the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. A supremely gifted artist whose work spans folk traditions, surrealism, and abstract expressionism, Sobel deserves wider recognition for revolutionizing 20th century art during a meteoritic career that was cut short by the patriarchy of her time.

About the Contributor