©Van Vechten Trust | Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

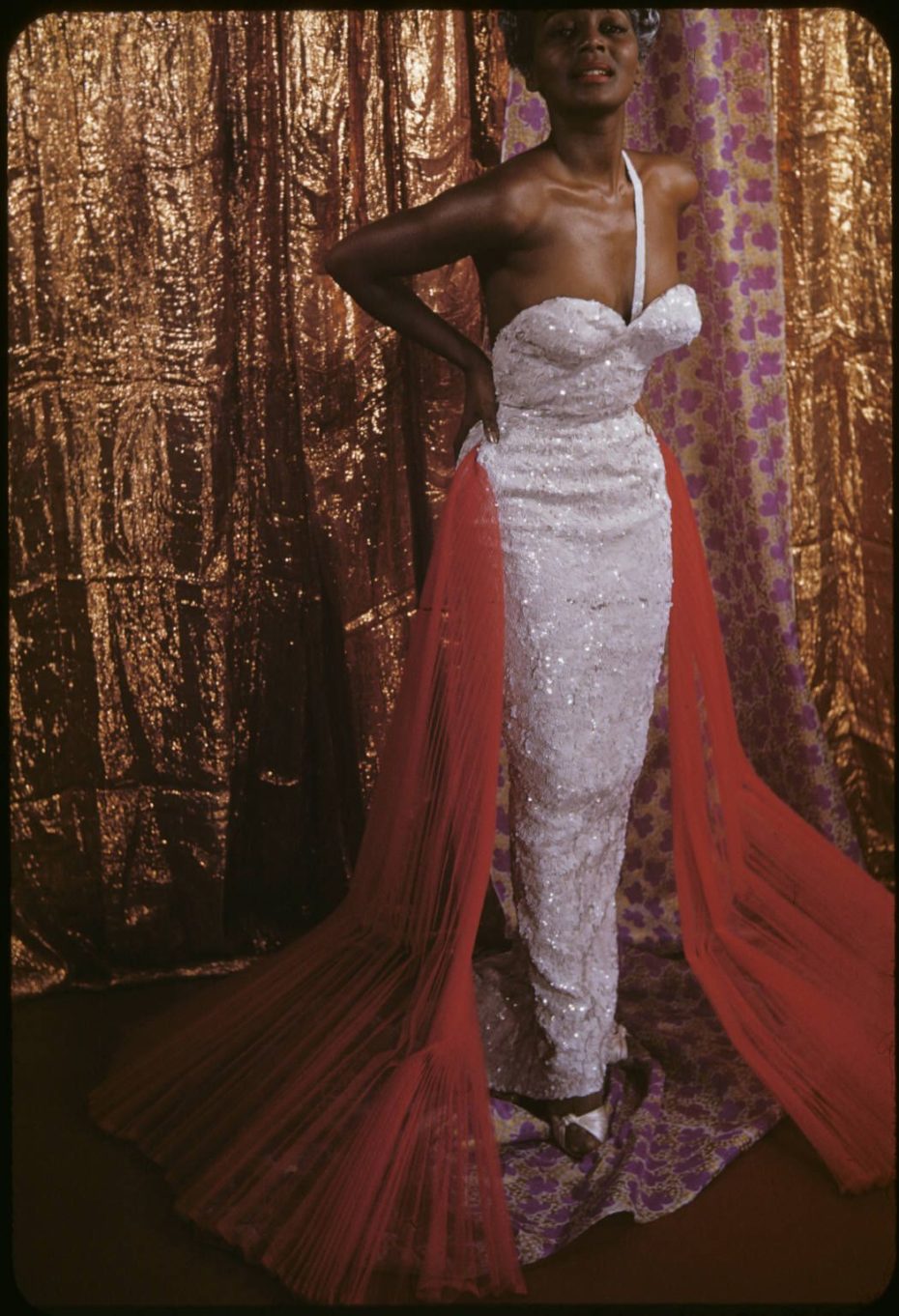

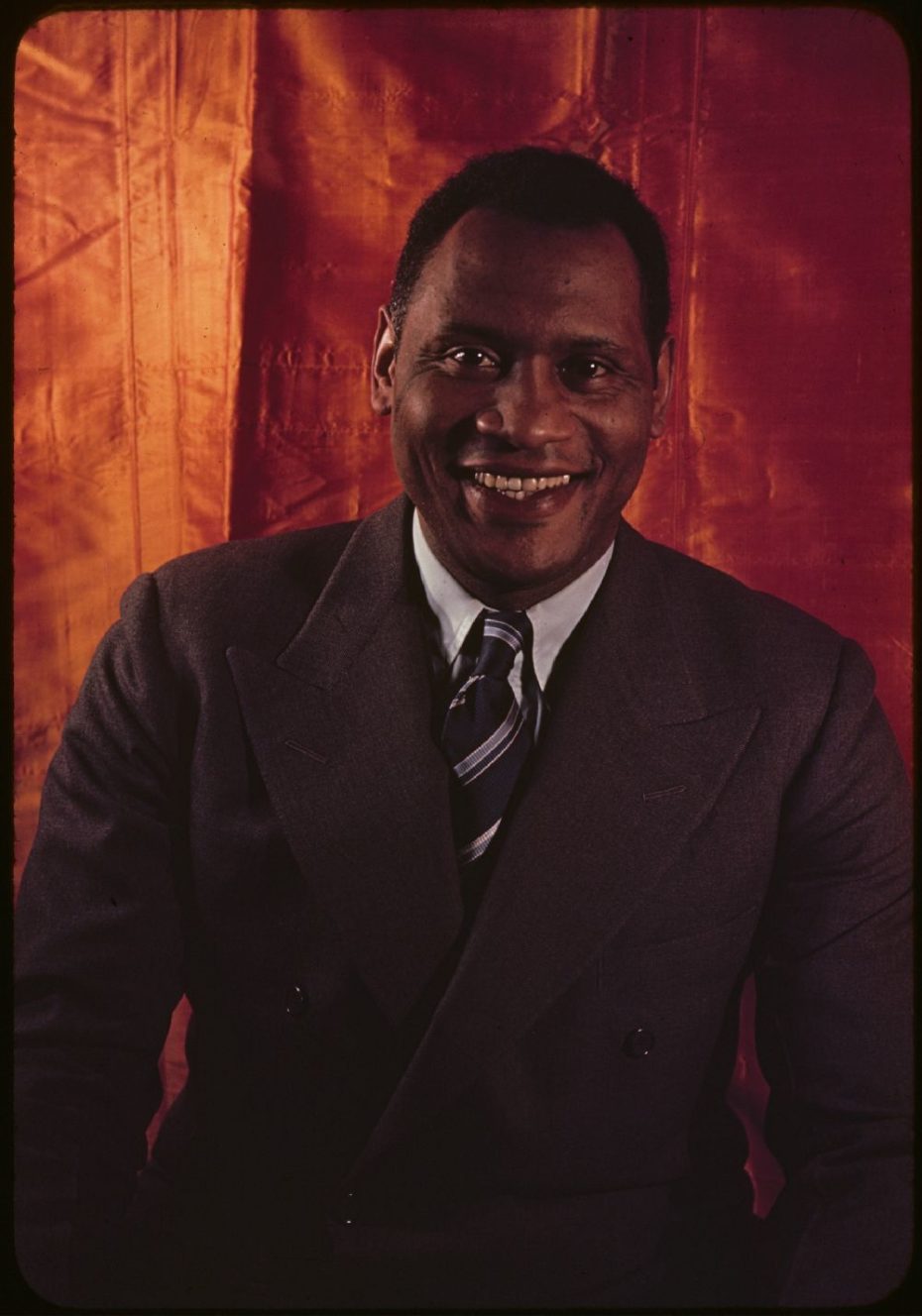

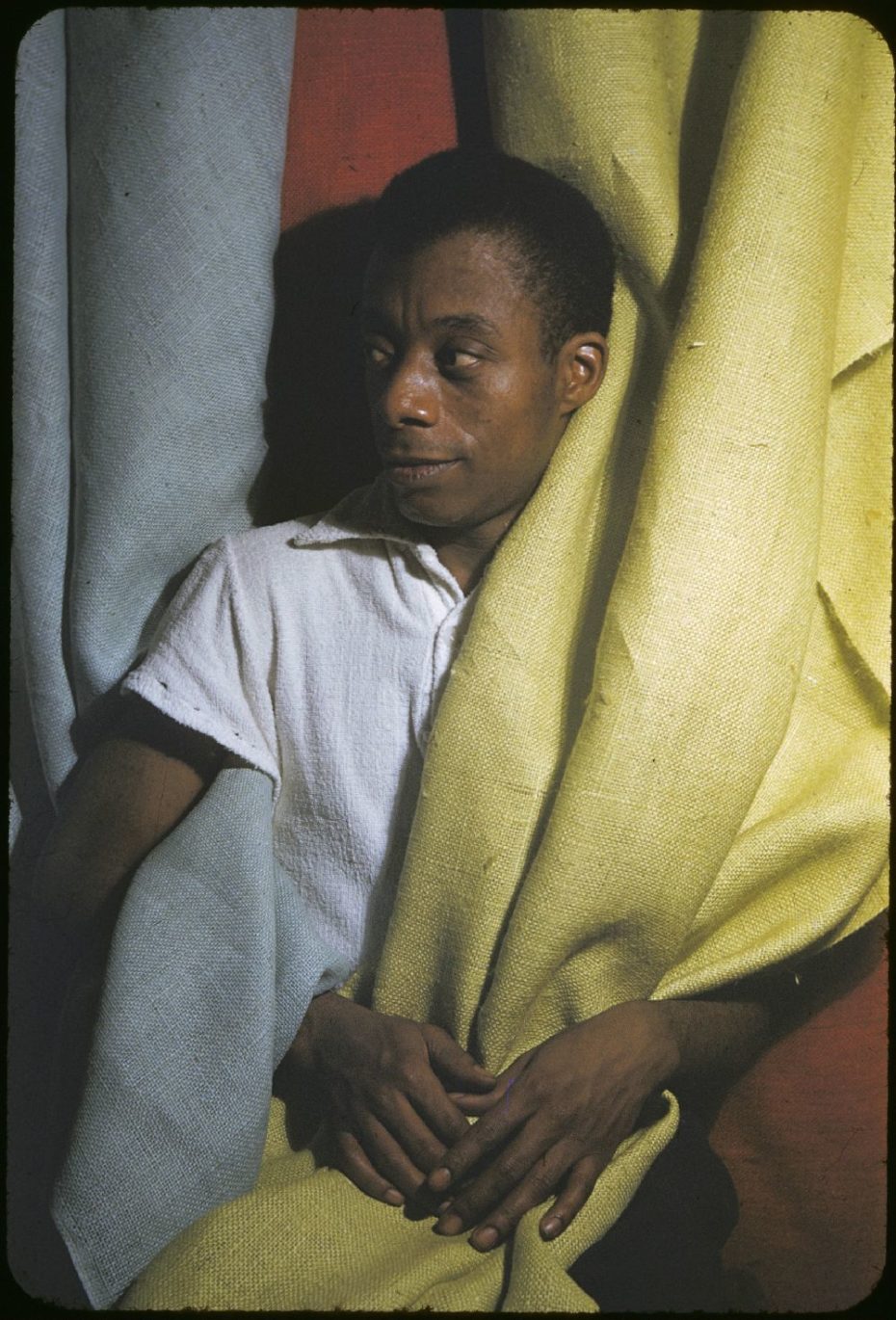

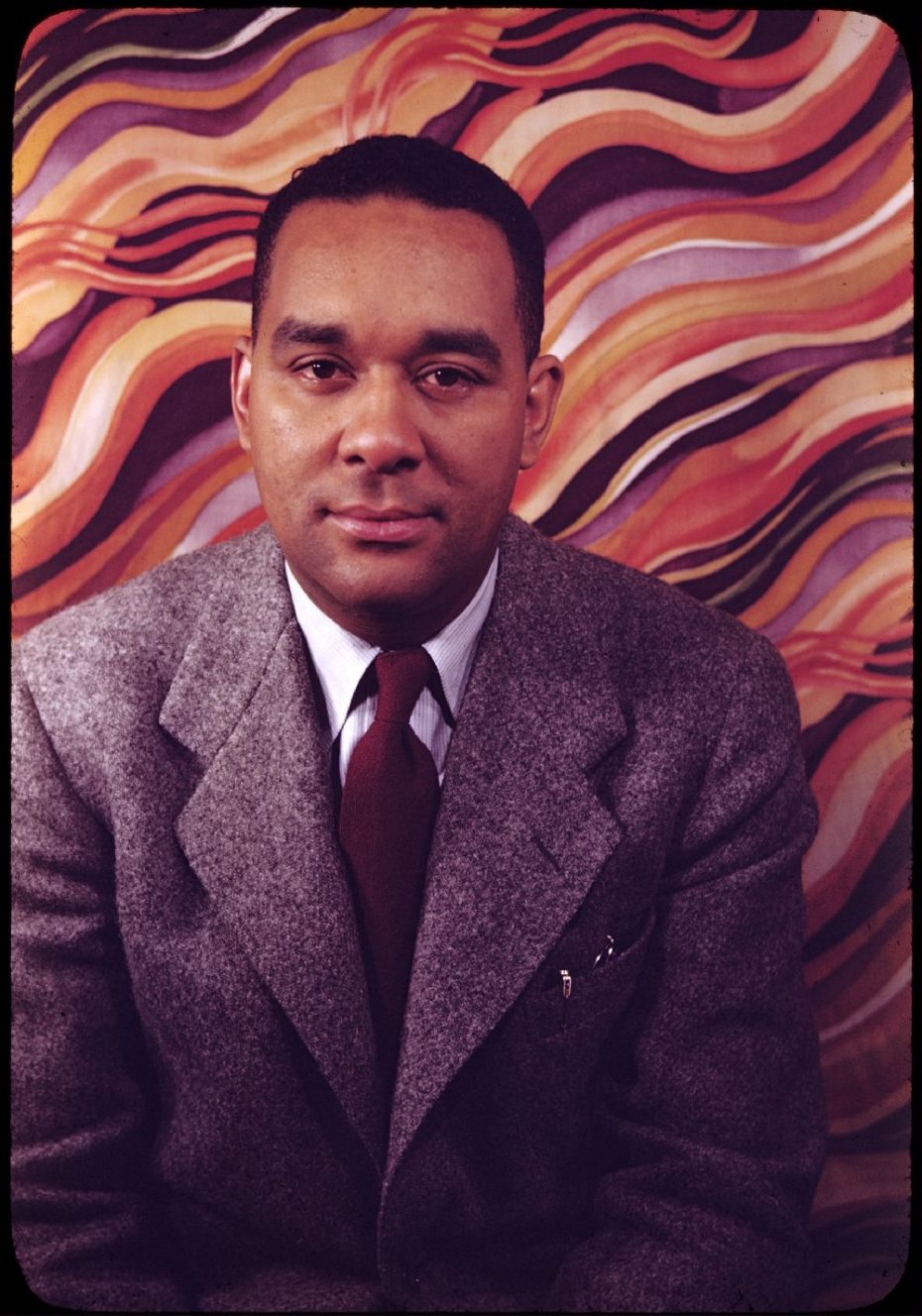

Thanks to Carl Van Vechten, we have glorious colour photographs of all the leading Black intellectuals and artists of the 1930s to the 1960s. A wealthy white patron of Black art, Van Vechten was a controversial figure during his lifetime and remains so today. There is no denying, however, that he helped to bring world attention to the Harlem Renaissance and catapulted the careers of several Black writers and artists, among them Langston Hughes, Paul Robeson, and Zora Neale Hurston.

©Van Vechten Trust | Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

©Van Vechten Trust | Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

Van Vechten was born in 1880 to a wealthy and progressive family in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. He studied at the University of Chicago, where he became acquainted with the first generation of Black performers who were starting to emerge through ragtime and the cakewalk. In 1906, he made his way to New York City and was soon employed by the New York Times as a music and dance critic. Though his homosexuality was an open secret, he married twice, first to a childhood friend, and then to actress Fania Marinoff.

A bon vivant who thrived off provocateurs, Van Vechten became obsessed with Dadaist writer Gertrude Stein after becoming acquainted with her through the heiress Mabel Dodge. Van Vechten was the first to sing Stein’s praises in The New York Times, calling her a “cubist of letters.” He penned “How to Read Gertrude Stein” for the arts magazine The Trend in 1914 and persuaded his friend Donald Evans to publish Tender Buttons, which turned Stein from a remote cult figure into an avant-garde celebrity. After Stein’s death in 1946, he became her literary executor.

In 1924, Van Vechten read Walter White’s novel The Fire in the Flint about race riots in Atlanta. Captivated, he asked the publisher, his friend Alfred A. Knopf, to introduce him to White. Within weeks, he was a “professional Negrotarian” as his friend Zora Neal Hurston later dubbed him. The Harlem Renaissance was just getting into swing and Van Vechten became its biggest cheerleader.

Ignoring both Prohibition and segregation, Van Vechten and his wife invited leading Black intellectuals and artists to their apartment for boozy parties that were written up in the society pages of leading Black paper The Amsterdam News. He legitimized and promoted the work of Black artists through writing about them in major periodicals like The New York Times and Vanity Fair. And then in the early 1930s, Mexican painter Miguel Covarrubias introduced him to the Leica camera. Vechten became obsessed with what he called the “magical act” of photography.

©Van Vechten Trust | Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

©Van Vechten Trust | Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

©Van Vechten Trust | Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

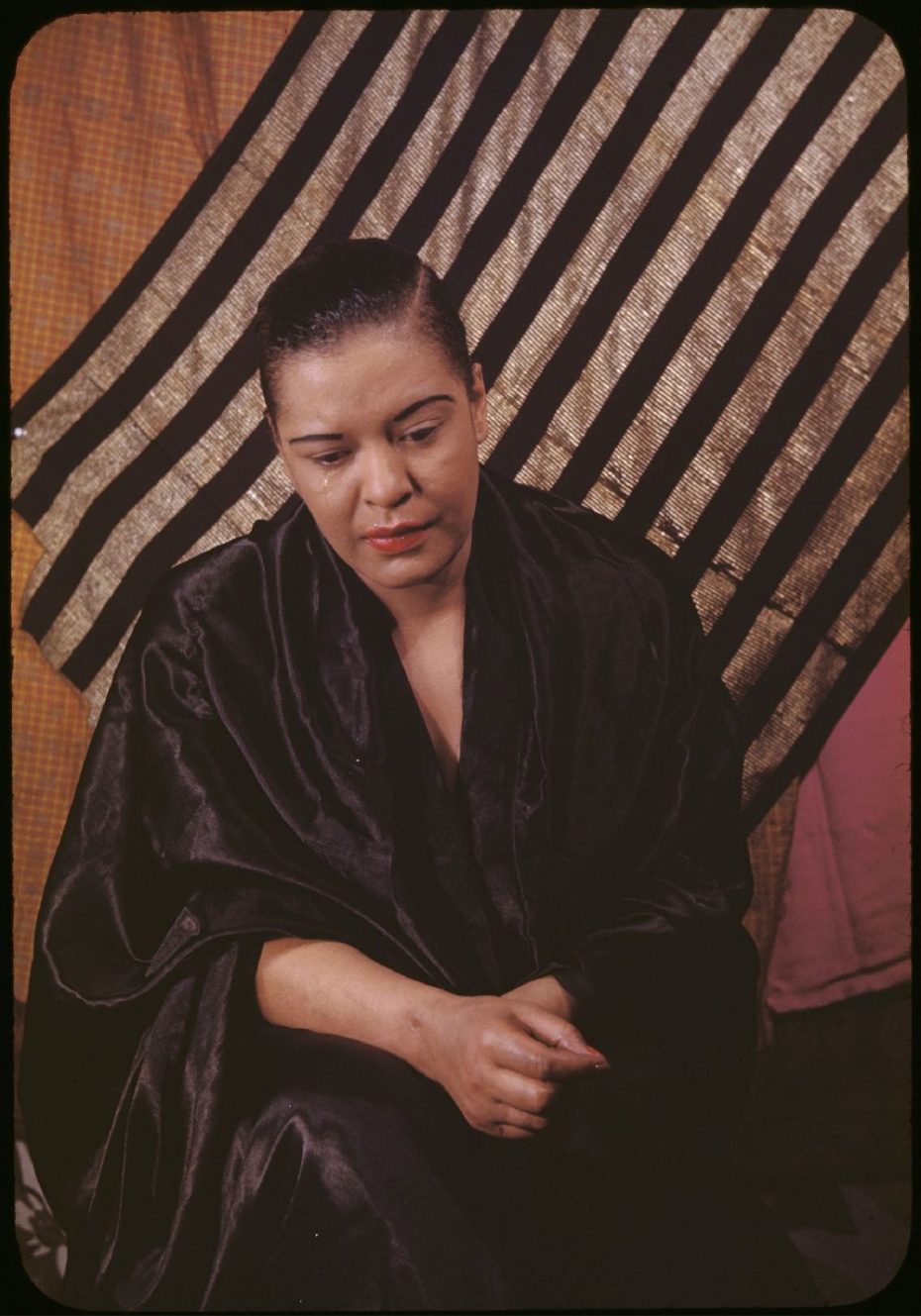

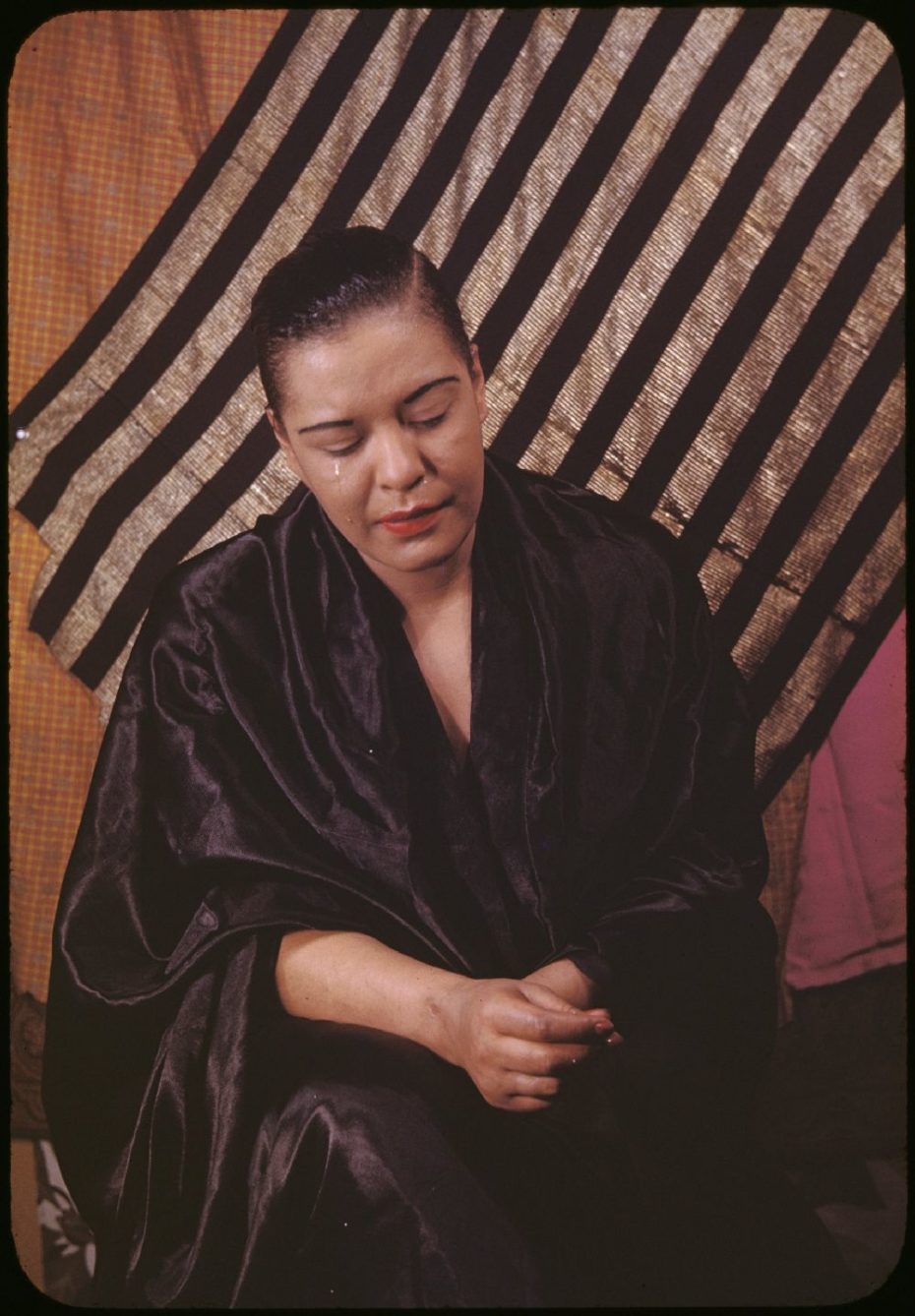

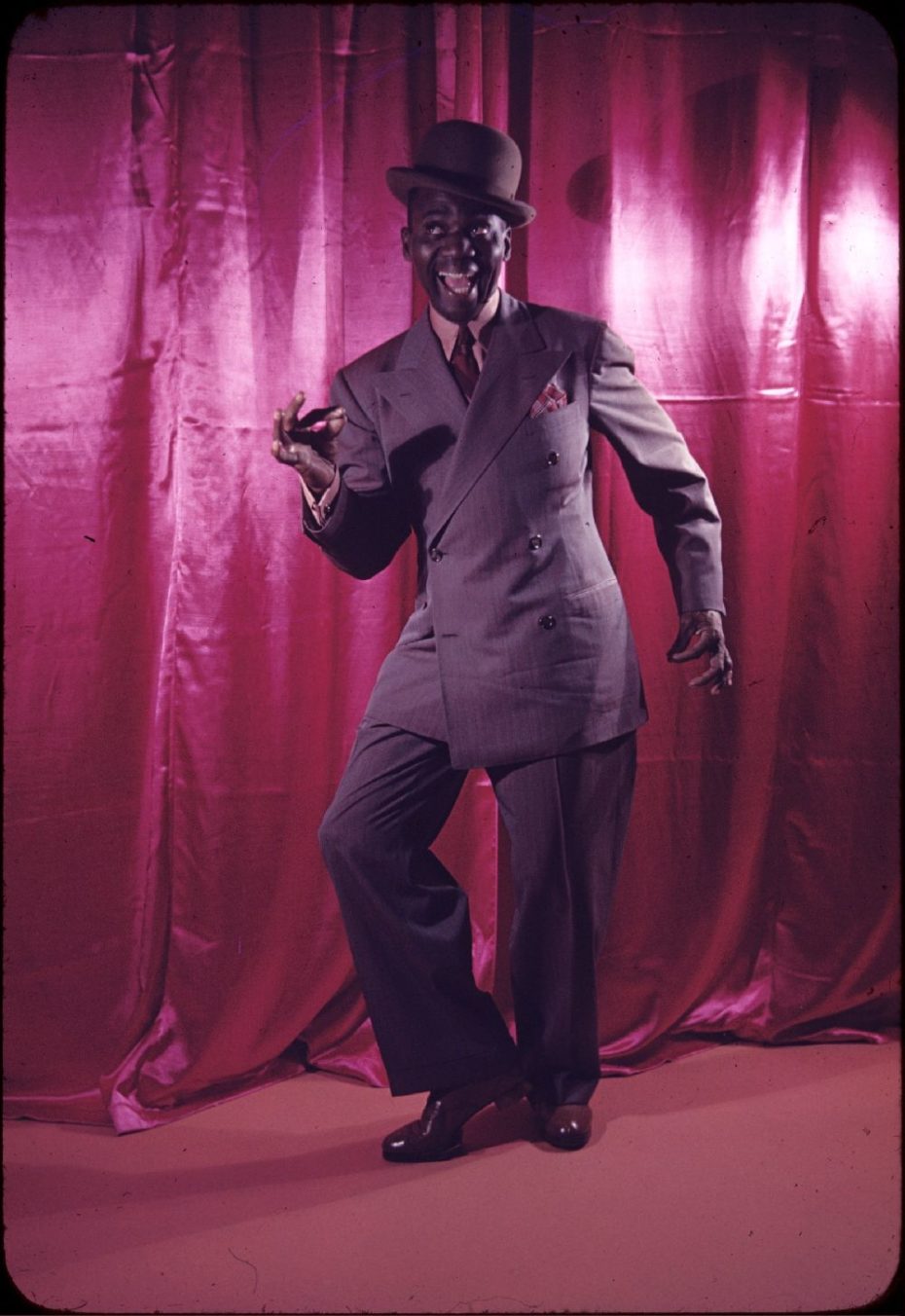

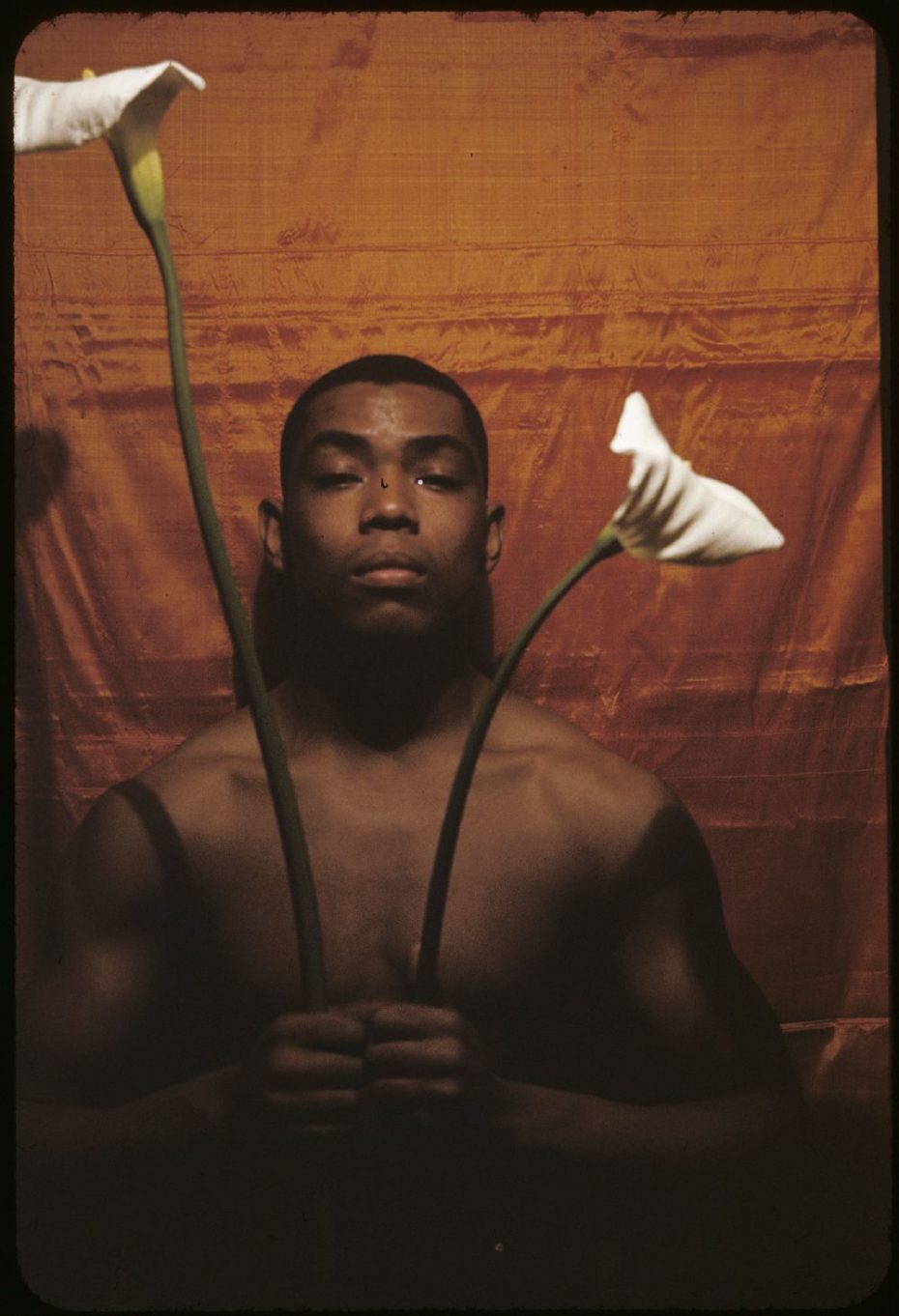

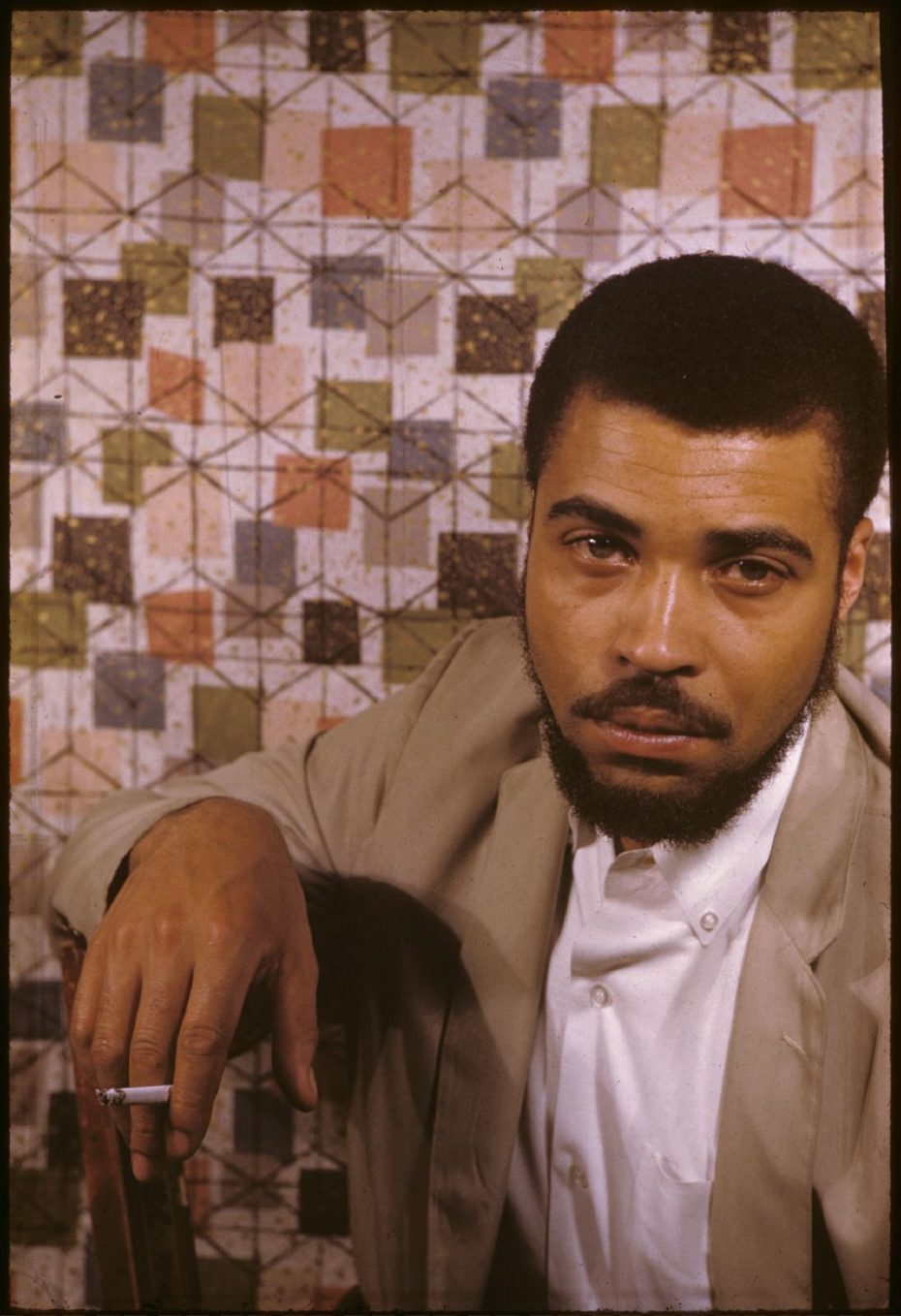

Van Vechten photographed everyone he knew, but he especially sought out Black artists and writers. “I am certain that my first interest in making photographs was documentary,” he later stated, “I wanted to show young people of all races how many distinguished Negroes there are in the world.” Van Vechten eventually gave up writing to devote himself to photography. In 1939, he switched to color film, after discovering the vibrancy of Kodachrome.

Van Vechten’s portraits are more endearingly intimate than technically adroit. He persuaded the greatest African-American talents to come to the cramped studio in his apartment, where he posed them in front of boldly patterned fabrics. His greatest gift was his ability to get his subjects to open up. He’d offer them a glass of champagne and they would begin talking. Once they were suitably loose, he would photograph quickly “in about a twentieth of a second.”

©Van Vechten Trust | Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

©Van Vechten Trust | Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

Occasionally, it took more than a few glasses of champagne. When Billie Holiday came for a shoot in 1949, he allegedly struggled for two hours to break through her sullenness. It was only when Van Vechten retrieved a photograph of Bessie Smith that Holiday let her guard down. “She began to cry,” he recalled, “and I took photographs of her crying, which nobody else had done.”

©Van Vechten Trust | Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

©Van Vechten Trust | Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

Financially secure, Van Vechten never sold his photographs, nor were his photographs published in periodicals. He did, however, exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York and at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. He continued photographing until he died in 1964, creating nearly 2,000 photographs that are available for viewing at the Library of Congress and at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University.

©Van Vechten Trust | Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

©Van Vechten Trust | Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

©Van Vechten Trust | Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

©Van Vechten Trust | Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University