Strasbourg is famous for its massive Christmas markets, white wines and fairytale architecture, but this city also has a unexpected cultural treasure – hidden in a 17th century water tower. The Chateau Vodou is home to the largest collection of Voodoo artifacts (Vodou is the French spelling) in the world. It includes over 1,200 pieces, including a “living” fetiche, a sacred object named Kéléssi that until recently, was regularly offered alcohol and the blood of sacrificed chickens.

© Claude Truong-Ngoc

Benin is believed to be Vodou’s place of origin, where it has been recognised as an official religion since 1989. Today, France is home to around 30,000 Beninese people, 30,000 Nigerians and 62,000 Haitians (the religion was also made official in Haiti in 2003), as well as 12,000 Togolese and 10,000 Ghanaians, the majority of which live in Alsace. While the museum serves as a rare educational landmark and dedication to African culture, particularly for the region of Alsace, in 2022, it begs the question: how did the largest collection of West African Voodoo objects end up in Eastern France, owned and exhibited by White curators?

The story begins with a sorcerer just outside Strasbourg, near the French and German border…

The Chateau Vodou museum is the lifetime work of Marc and Marie Luce Arbogast. As a teenager, Marc became fascinated by a witch in his village in the Vosges region. This local conjurer would heal animals with plants and potions. While witches in wine country might not fit neatly in our stereotypes, unexplained oddities, such as the dancing plague of 1518, have been known to happen in Alsace, where spiritual folklore remains a part of the culture.

©M. Wittmer

In the 1960s, Marc and Marie Luce traveled to West Africa for the first time, and as they moved from one village to the next with a large suitcase of medical supplies for locals, they encountered a rich tradition of pharmacopeia administered by “Bokonos” (voodoo healer and priest). This started the couple’s lifelong enchantment with Voodoo and they began collecting the foundational pieces of the museum.

Although there are some artifacts from dealers and other museums, the majority of the pieces come from the couple’s personal collection. Marc and Marie Luce acquired their pieces directly from the Bokonos in West Africa. Over the years, they collected so many objects that they had to get a second apartment just to store them all. They said it was like their “secret garden,” but they felt a calling to share it with the public.

In 2014, they were able to open a museum in an historically preserved water tower (“chateau d’eau” in French). The unique building thus earned itself the name “Chateau Vodou.”

©Ji-Elle

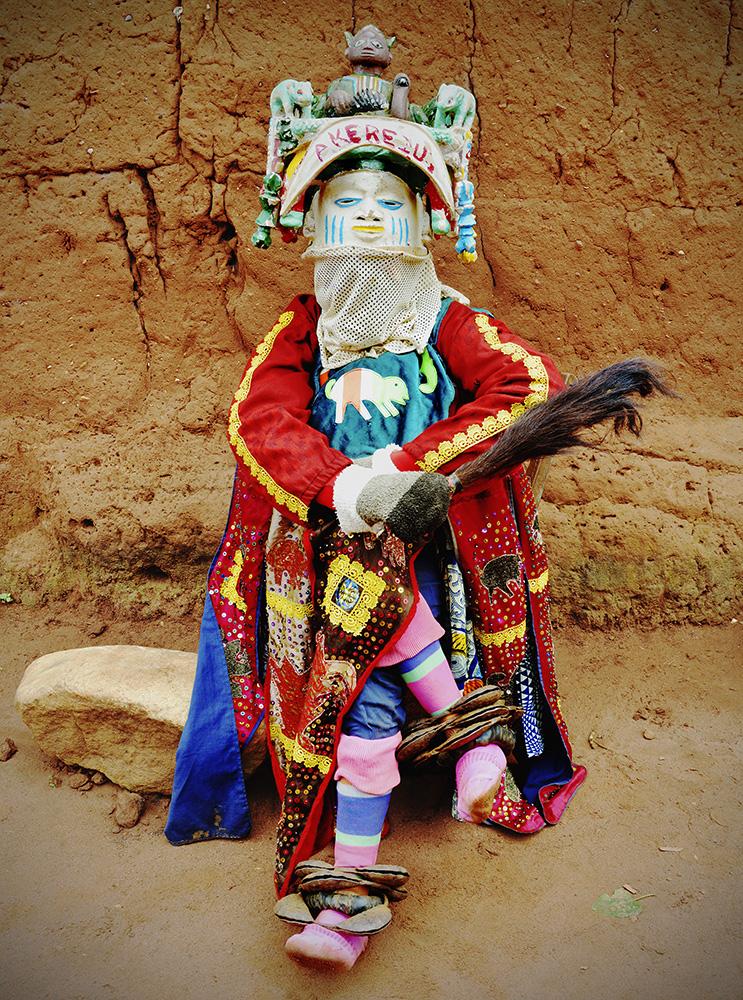

During the height of Black Lives Matter protests in 2021, a photograph from the museum’s Facebook page showing two White women handling Egunguns (large traditional costumes which represent the ancestors in West Africa), went viral online for all the wrong reasons, and the museum found itself at the centre of accusations of cultural appropriation. In response, the museum’s representative first acknowledged that there “may have been a communication problem … We may have gone too far and may have lacked tact”. The director of Chateau Vodou, Adeline Beck, went on to outline why the photograph had caused such a stir….

“Voodoo is a religion that is still very much practiced and alive. Showing sacred objects as part of an exhibition as an art object can represent a form of disrespect for them,” said Beck. She also pointed out the fact that the objects were handled by women (traditionally forbidden, although over the years the exclusion of women from this cultural practice has generated heated arguments from human rights activists and feminists). “In order to preserve and protect the objects that make up this collection, it is necessary to maintain them, to clean them,” Beck explained, noting that the museum’s team includes several West African practitioners of the religion. “This is why we allow ourselves with great care to touch them: we know their history and their specificities … These formerly sacred objects have become, because of their museum context, desacralized. However, we remain fully aware of their spiritual charge and that is why we seek to preserve them, protect them, treating them with the greatest respect.”

It appears that the collections only “active” fetiche has since been removed from exhibition and is no longer ceremoniously offered nourishment by the museum. There is no mention of the fetiche known as “Kéléssi” on the website either, which was made by a Togolese priest as an offering to protect the museum and its collection.

Most glaringly, the question of the restitution of objects looted or stolen during French colonization had been raised. In suggesting that there might be “a lack of knowledge [about] our establishment”, the director added that it was a non-profit association and that the objects in the museum come from a private collection, which were acquired or donated. “None of them have been looted or stolen”.

© Claude Truong-Ngoc

While Voodoo originated in West Africa, it took root in the Americas via the slave trade. Beck affirmed that “our work also consists of addressing these horrors of the past to preserve a duty of memory.”

Much of our understanding of Voodoo today are still shaped by colonial attitudes, and more recently, by Hollywood. The Chateau Vodou attempts to combat clichés by decodifying the religion.

©M. Wittmer

Like many religions, Voodoo holds that the visible world is created by events in an invisible, spiritual world. Conduits, like ancestors and plants, can be used to access the secrets of the invisible world. Practitioners use different vehicles, like music, dance, rituals, seances, trances, costumes and fetiches to communicate with an estimated 300 different gods and goddesses. Chateau Vodou seeks to showcase the similarities in Western-European and West-African mystical experiences – just as Marc found with both the sorcerers in the Vosges and Bokonos in Benin.

©M. Wittmer

If you’re looking to understand the cosmic connection between the visible and invisible worlds, the Chateau Vodou has an incredible collection full of profound histories, objects and experiences for you to explore. The question of whether its current location is entirely appropriate, remains open for debate.