When Nellie Bly got bored of writing about fashion and gardening, she went undercover as a patient in a mental asylum and faked insanity to expose the institutional abuse. When she read Jules Verne’s book Around the world in 80 Days, she attempted the fictional journey herself, and did it in 72 days, 6 hours, and 11 minutes, setting a world record as the first person to do so. When she married and was expected to become a housewife, she patented two designs for steel cans and became the boss of a million-dollar iron manufacturing business instead. This was all before the age of 40, and before women had the right to vote.

Nelly Bly was a daredevil writer and pioneering investigative ‘stunt’ journalist on a mission. Ahead of her time as she was hell-bent on promoting social change, she felt compelled to champion the cause of neglected and exploited women in the rising industrial world of the late 19th century.

She was born Elizabeth Jane Cochran in 1864 at Burrell Township, Pennsylvania USA, and one of 15 children from an impoverished and extended family. Her father died when she was six, and although having been a successful local businessman owning the local mill, this seems to have had little benefit to Nellie. In 1880, Cochran enrolled at Indiana Normal School (now Indiana University of Pennsylvania) but after a year, had had to drop out due to lack of funds.

Her first skirmish within the world of journalism occurred in her early teens when she wrote a strong and feminist letter to an editor objecting to an article that had appeared in the “What Girls are Good For” column of her local Pittsburg paper, The Dispatch. The article claimed that women were ‘only good for giving birth and doing housework’.

The paper’s editor, George Madden, was so bowled over by Nellie’s response that he asked her to write an official reaction article under the pen name ‘Lonely Orphan Girl’. In her first Dispatch article, ‘The Girl Puzzle’, she passionately penned how divorce adversely affected women and appealed for change to the divorce laws of the day. Madden offered her a full-time position using the pen-name Nellie Bly, based on a popular Afro-American song character from 1850. The name stuck.

Writing for The Dispatch provided the foundation for her future journalist exploits. Nellie was determined to advance her exposé of the unsavoury and unfair working practices for women and promote legislative change, but inevitably, her articles attracted complaints from factory owners. She was ‘demoted’ to the women’s section of the paper to cover the ‘safer’ and less contentious subjects of fashion and gardening. Frustrated and determined, she vowed “to do something no girl has done before” and insisted on being given an assignment to Mexico as foreign correspondent for The Dispatch. Her subsequent writing explored and exposed the lives and customs of the Mexican people, including the horrors of employment in some local factories. Whilst in Mexico Nellie stuck her neck out even further and reported on the cause of persecuted local journalists, covering the brutal dictatorial regime of the then President Diaz, whose threats of arrest then sent her fleeing the country. Nellie’s sojourn to Mexico was later published as a book ‘6 Months in Mexico’.

Nellie returned to The Dispatch in Pittsburg, this time reporting on the Arts. Unsatisfied, she left the paper and Pittsburg for New York in 1887, hoping her reputation would land her a high profile journalistic position. But she could only secure an offer for undercover work for the New York paper, The World. It turned out to be a blessing in disguise, as one undercover assignments would be Nellie’s calling. It was dangerous and dastardly and required her to fake insanity to get herself inside the Women’s Lunatic Asylum on Roosevelt Island and to pen a report on the rumoured brutal and neglectful residential conditions for the publication.

Nellie’s impetuous, daring and perhaps reckless nature was perfect for this quest. For starters, she had to get herself classified as ‘insane’ by a doctor, policeman and judge. To look the part of a haggard and drawn ‘madwoman’ she purposefully deprived herself of sleep for nights. She then joined a woman’s refuge where she deliberately instigated chaos by behaving badly and making false accusations regarding the sanity of other residents. Nellie succeeded in her covert social psychology experiment: she got her certification and was promptly transported to the notorious Roosevelt Island facility. The World obtained her release ten days later and her reports of the deplorable conditions she had witnessed and endured first-hand, were published for all to see. The article and later the book ‘Ten Days in a Mad-House’ captivated the public and the outcry ushered in reforms in social care, not just at Roosevelt Island, but across the USA.

“My only regret,” said Nellie, “is not poisoning more nurses”.

By now she was adored by the press and public alike and was dubbed the first ‘stunt-girl’ reporter. The event had ushered in an age of couverte journalism or ‘detective’ reporting (rampant, yet frowned upon today for obvious ethical reasons) championed and exploited by the owner of The World, Joseph Pulitzer.

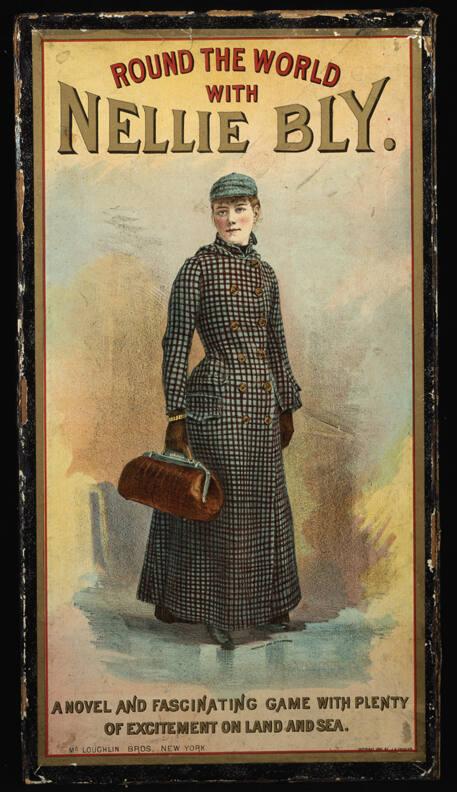

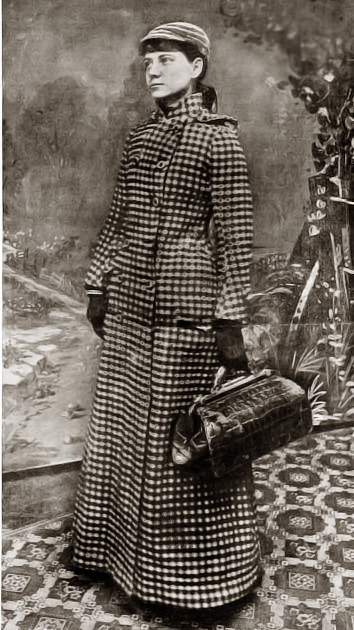

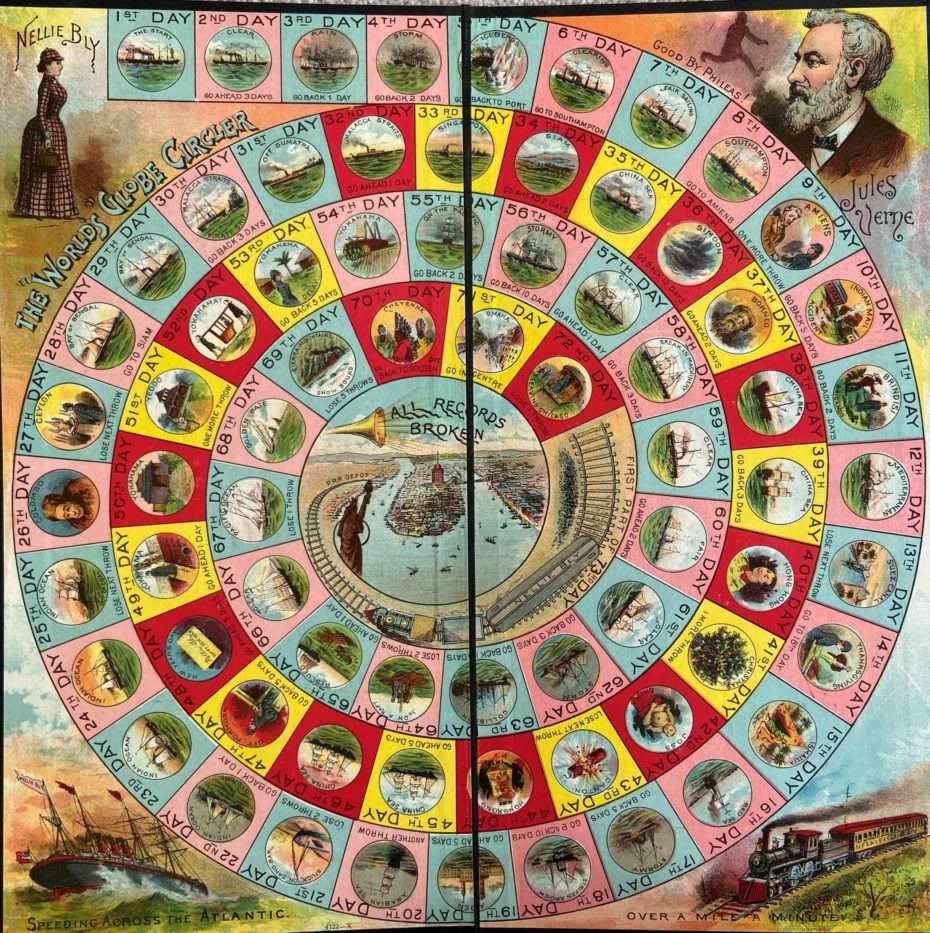

Forever restless and somewhat of a madcap, Nellie was hungry for yet another epic journalistic exploit. In 1888, following the described itinerary of Jules Verne’s now legendary novel Around the World in 80 days, Nellie proposed to beat the fictitious journey time and establish her own record, write about it on the way, and of course, attract more public attention. The World agreed and one year later on November 14th 1889, she embarked on the steamer Augusta Victoria for Europe. With the clothes on her back, an overcoat, bag of toiletries, two hundred British pounds, some dollars and a little gold for emergencies, she set off on her quest. The journey became even more interactive in engaging the public when the paper decided to run a concurrent competition for guessing when Nellie would arrive home. A rival paper The New York Cosmopolitan put up their own traveller, also a woman, Elizabeth Bisland, in competition. A board game with swirling graphic representations of the journey and depictions of all Nellie’s travel modes, was sold as a novelty.

When she returned on January 26th 1890, Nellie had traversed England, France, (where she met and interviewed Jules Verne), Italy, Africa’s Suez Canal, Ceylon, Singapore, Hong Kong, Japan and back to the USA. Very much a maritime endeavour, the short land crossings were undertaken by rail over mainland Europe and back across the USA, where The World had laid on a private train for her return to New York. The newly-laid subsea cables and the invention of the electric telegraph gave Nellie the ability to send short progress reports supported by longer overland and oversea mail. When delayed by travel arrangements, Nellie allegedly made the most of her time, visiting a leper colony in China and buying a monkey in Singapore. She arrived back in New York seventy two days, six hours and 11 minutes after her departure from Hoboken, New Jersey, beating her ‘opponent’ to the first place in the race. Nellie was a national treasure.

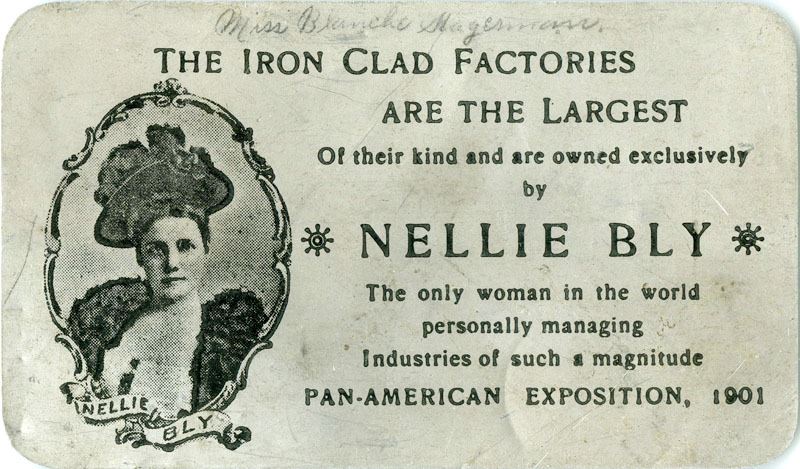

At age 31, in 1895, she embarked on another life and career change by marrying ageing millionaire Robert Seaman, 62 years her senior and in failing health. As if the age difference wasn’t challenging enough, Nellie abandoned her tried-and-tested career of journalism to run Robert’s steel container business, the ‘Iron Clad Manufacturing Co’. Robert died in 1904, leaving Bly, determined the factory should be run as a model employer incorporating all the best labour welfare and employment practices, at the helm.

In parallel with the day-to-day running of the business, she also dabbled in design and patented a new metal milk can. For a period she was a highly regarded industrialist in USA manufacturing circles. Well intentioned, but perhaps naive, a hapless Elizabeth lacked the necessary business finance acumen, and at the same time, was taken for a ride by the fraudulent accounting of her works’ manager. Both factors soon drove the business to a costly bankruptcy.

With the outbreak of World War 1, Nellie was back in the journalism saddle, this time risking it all as a war correspondent on the European Eastern Front. She was arguably the first female and foreign correspondent to visit and report from the Austro-Serbian conflict. Unfortunately, she was mistaken for a British spy and arrested (which, one would imagine, gave her the perfect opportunity to report on such an incident). During the war years, Nellie kept writing about women’s rights, focussing on women’s suffrage, which was eventually granted in America in 1920.

Elizabeth Jane Cochran, also known as Nellie Bly, died from pneumonia in New York on January 22nd 1922. Nellie’s legacy is that of a restless spirit determined to draw attention to the inequalities suffered by women in society. Perhaps a relentless self-publicist through her crazy escapades, she had her own recipe for putting the spotlight on the need for social and legal change. Moreover, she never shied away from risking her life in the process. Nellie Bly will undoubtedly be remembered as a contributor to women’s suffrage and welfare improvement, an entrepreneur and humanist, but it is her role as the first ‘stunt-journalist’ – perhaps even the first female pioneer of modern investigative journalism – that has immortalised her in the psyche of future generations.

If you think Nellie deserves a more prominent place in our school’s history books as a role model to more young women, do them a favour and share her story.