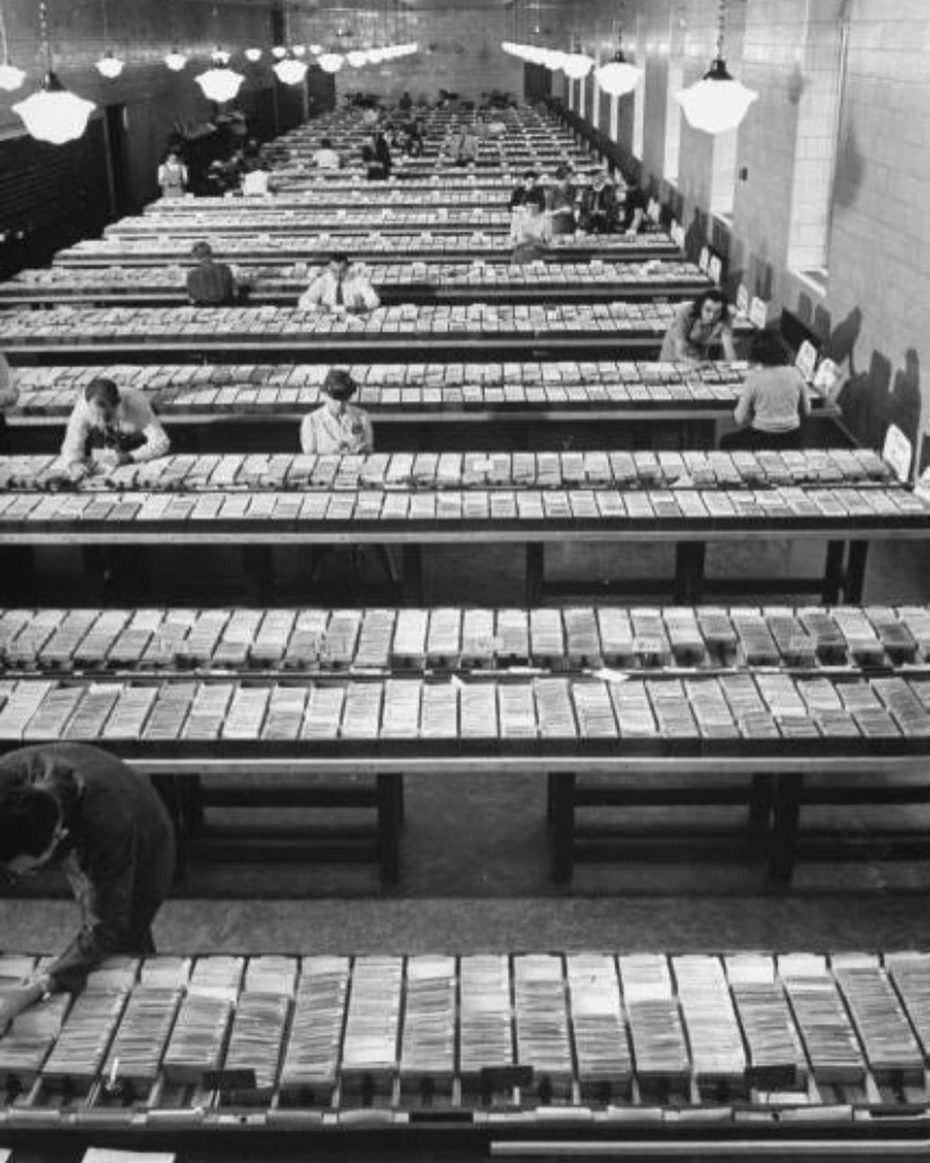

Before books were easily printed and accessible to nearly everyone, before they even took the form of books specifically, there was a different story. Information was scarce in its written form, and so scribes and scholars developed a meticulous system for organizing libraries of tablets. That’s right: the oldest known form of organizing books predates the books themselves. We have, of course, come a long way since then. Depending on your age, you might remember the tiny envelope with the stamp card in the back of your library book. That, friends, is a remnant of the Dewey Decimal System, a relic of the card catalog used in libraries for 200 years. In the age of the internet, one would think that the obsolete card catalogs have disappeared, but true to form, collectors dedicated to organizing written volumes have turned to collecting the organisation forms themselves.

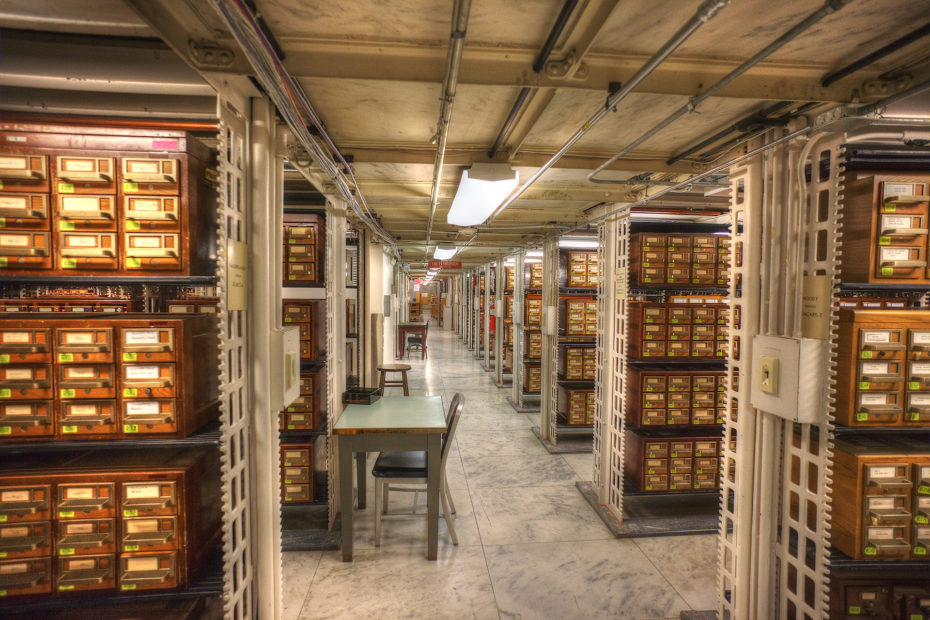

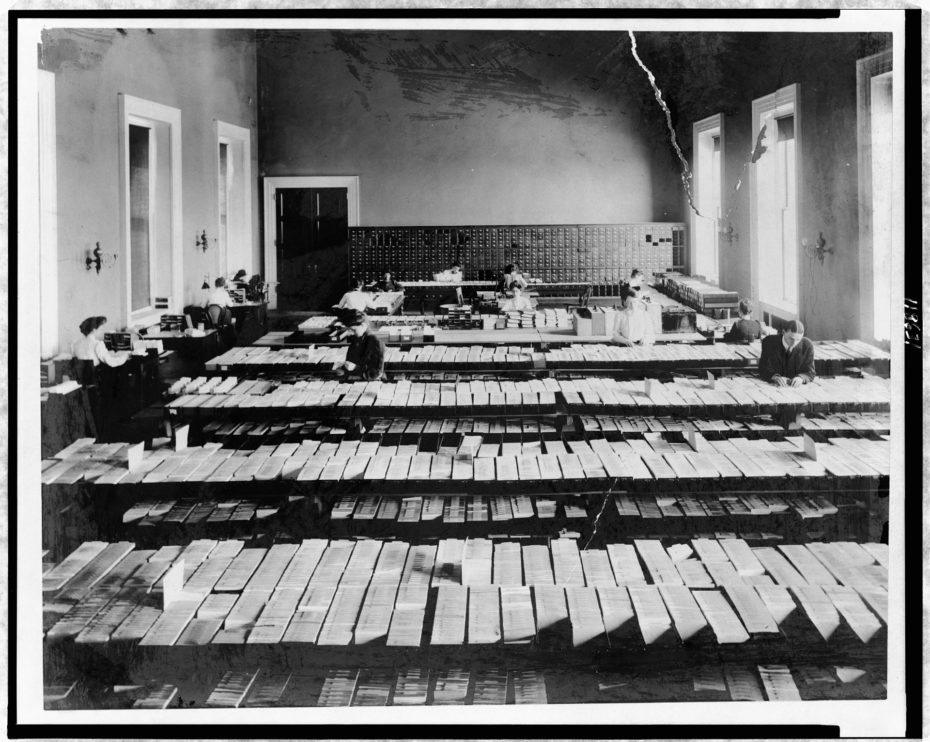

The Library of Congress still holds its entire (paper) card catalog, which is currently gathering dust in the basement, essentially a relic abandoned by modern society. Supposedly, they keep it there for older patrons who occasionally use it, but the catalog remains an important historical archive.

As of 2015, the Library of Congress site says, “You might be surprised to learn that we still sometimes use card catalogs in the Prints and Photographs Reading Room, where our cards typically lead to photographs, drawings and other visual materials, rather than books. While much of the content on the cards has been converted and added to our online catalog, some unique indices are still in use today by librarians and researchers alike.”

If you’re interested, you can still visit the Library of Congress Card Catalog (while it’s still there).

Similarly, you can visit the California Historical Society Headquarters in San Francisco. It’s a former hardware store, but now it’s the official home of California’s history, complete with a catalog of its contents.

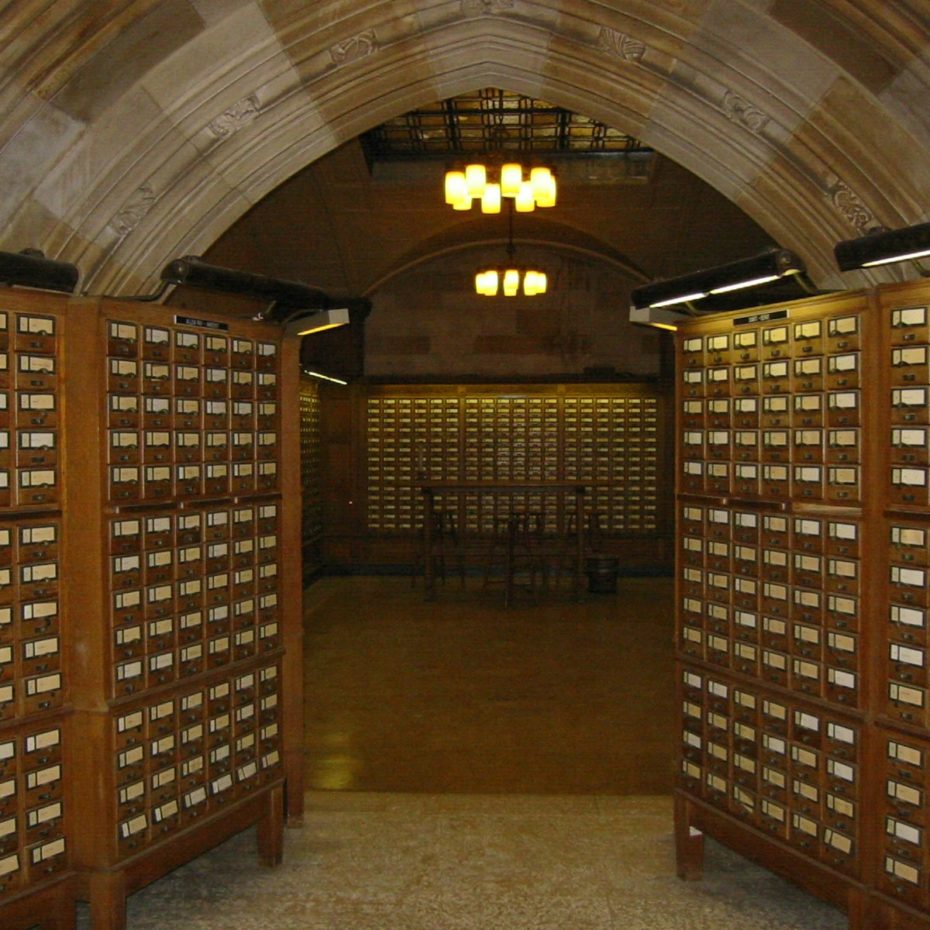

The Young Men’s Institute Library in New Haven, Connecticut is one of America’s oldest private membership libraries. It has a unique card catalogue with its own organisational scheme and a rather eccentric catalog system invented by librarian William Borden. One source says, “Under Borden’s scheme, fiction is categorized by its subject matter, and books on nihilism and socialism share a common call number.”

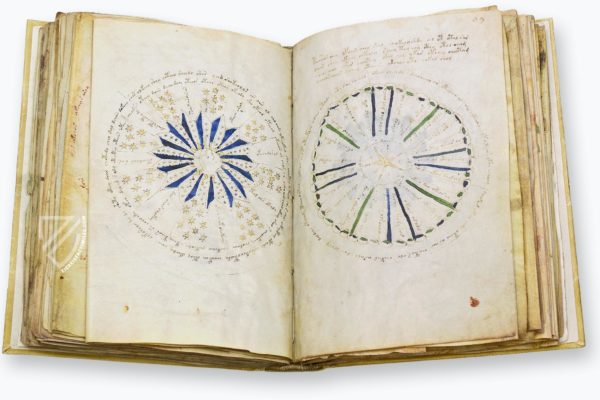

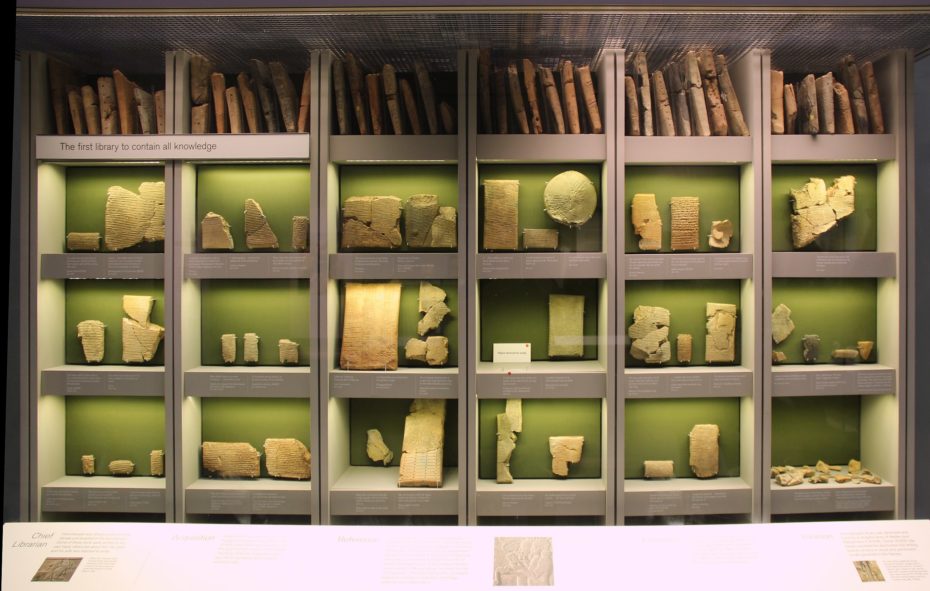

The first known library catalog dates back to 2000 B.C. in the Sumerian city of Nippur, where a tiny 2.5 x 2.5″ clay tablet that listed 62 literary works. To put this in historical relief, The Epic of Gilgamesh is included in this list. Library cataloging has been around almost since writing has been around (and scholars think that happened around 3500 BCE).

Moving on, 1300 years later, in 7th century BCE, the royal library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh (upper Mesopotamia, present-day Iraq), housed 30,000 clay tablets. The scholars there organised the tablets in two ways, by shape and by content. After all, they were storing big, flat rocks, so efficiency necessitated practicality.

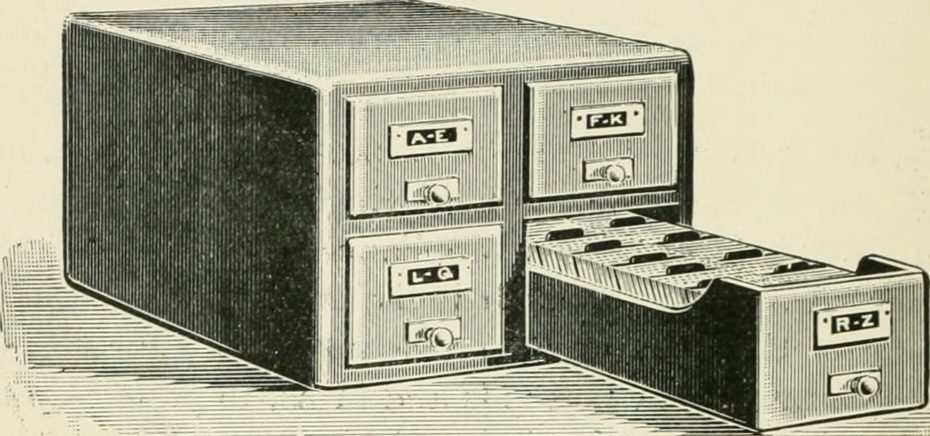

The more modern system that was used in libraries up until about the end of the 2000s, started with a catalog of cards to manage the personal book collection of Francis Ronalds, a 19th century English scientist and inventor, who pioneered the first practical use of this system. The mid 1800s saw the Italian publisher, Natale Battezzati develop a similar card system for booksellers wherein cards represented authors, titles, and subjects.

Most historians credit the most major step of the evolution to a name some of us may recognise, even if we don’t know why. American librarian and educator, Melvil Dewey championed the card catalog because it was so easily expandable. Weirdly, during the late 1800s, libraries were still cataloguing based on the size of the book (even though they were working with actual books now, and not tablets), whereas some libraries organised only by the author’s name. Dewey standardised the system; he organised the books first by subject, and then alphabetised them based on the author’s name. Each book got assigned a call number to identify the subject and location. The number on the card matched the number on the spine of every book.

Within the first year of development, 35,762 catalog cards, measuring 2.5 x 5″ (not much bigger than the original Sumerian one!) were hand written. In 1908, the size was standardised, making manufacture of the cards and their cabinets uniform. In 1876, Charles Ammi Cutter solidified the objectives of a bibliographic system:

1. to enable a person to find a book of which any of the following is known (Identifying objective):

- the author

- the title

- the subject

- the date of publication

2. to show what the library has (Collocating objective)

- by a given author

- on a given subject

- in a given kind of literature

3. to assist in the choice of a book (Evaluating objective)

- as to its edition (bibliographically)

- as to its character (literary or topical)

That’s way easier than walking into the ancient Assyrian library and saying, “I remember it was about this big.” Or the contemporary equivalent: “I remember the cover is red.”

A more recent attempt to describe a library catalog’s functions was made in 1998 with Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR), which defines four user tasks: find, identify, select, and obtain.

Still, good things come to an end. The major supplier of catalog cards, OCLC, printed the very last one in October 2015. Card catalogs and their cabinets were so bulky that the librarians knew they were looming on an inevitable storage crisis, so with the invention of the computer, most libraries converted their systems. Still, like true scholars, librarians wax nostalgic over the catalog systems.

Though a few card catalogs remain accessible, there’s a rumour that the US government might try to auction off the one gathering dust in the basement of the Library of Congress. It wouldn’t be the first time the library’s collection is under threat. The British destroyed much of the LOC’s first collection during the War of 1812; they used it as kindling when they set fire to the White House and the Capitol. Thomas Jefferson offered his immense personal library (6,487 book) as replacement, along with his own personal classification system which the library used for a while.

If the LOC is now looking to offload their outmoded system, it’s probably because they’ve recognised that there’s a huge market for ordinary card catalogs for collectors. Today, cards alone can reach a minimum of 4 figures when sold at antique stores or auction. Artist Thomas Johnston acquired the card catalog from one of Harvard’s libraries. As artifacts,” he says, “they continue to be exciting to look through, to realize the creative activity, research, and information that each card represents, and further, how each card has played a role in advancing knowledge.”

Another artist, Matthew Passmore purchased some ephemera from a library outside of Deming, New Mexico in 2004. The idea was to “make it look like the [card] cabinet grew naturally out of the landscape; as if, in Cabinetlandia, cabinets are naturally occurring elements of the ecosystem.” He stocked the top drawer with a library card catalog, a guestbook, a pillow to sit on while you read, and an umbrella for shade.

To come full circle, the internet now has websites that offer ways to Re-use a Card Catalog. On Amazon, you can purchase a reproduction of a nostalgic library box tray, complete with 30 notecards and tabbed dividers. The aptly-named brand, Out of Print, has an entire Library collection including tote bags, socks and drink sleeves inspired by the card catalog to express your love of the stacks.

A Washington Post journalist described the Card Catalog as “a heady antidote to the technophilia threatening our culture” and quoted Peter Devereaux in declaring the catalogue “one of the most versatile and durable technologies in history.” You may find it comforting that indeed, you are not alone in your nostalgia.

The Library of Congress a fascinating book on card catalogs, available here.