The 18th century saw a decadent sexual revolution for the privileged, where the old-world pressures of church and state behaviour waned and the floodgates to libertine perversity opened. And Rococo art was this era’s erotic entertainment. Sexually charged painting and erotic literature were abundant, encouraged and consumed en-masse by all: from tacky prints and scratchy etchings to sensuous oils on canvas. A rather thin gloss of innocent love concealed an institutionalised frenzy for fleshy frolicking. What had remained unspoken and discreet in the bedroom could now be fantasised over and captured in paint, prose and poetry by the great artists of the day.

Sexual freedom was by no means an invention of the times, but elite society was now in a position to fully exploit its pleasures. Previously, sexual gratification had been contained under the veil of personal and religious responsibility, albeit disease was a threat and pregnancy and the resultant childbirth very serious risks. The Enlightenment of the 18th century had side-lined religion and precedent, the new world of the privileged Libertine was about political and financial power, while turning a blind eye to unplanned pregnancy and the plight of these ‘used’ women. The young and wealthy elite were taking their Grand Tours across the continent. Some enjoyed the intellectual and architectural sights, but many more sought out the semi-sordid indulgences and pleasures of being abroad. This was the time of the Libertines, such as the Marquis de Sade and Napoleon’s notorious pleasure-seeking brother, Joseph Bonaparte, and learned men devoid of morals, responsibility and most of all, sexual restraint.

Secure in the comfort of their grand and luxurious country estates, the elite could safely play, blissfully oblivious to the plight of the poor. The great country palaces and their lavish gardens of decorative woodland, avenues and vistas were the perfect settings for hot and sweaty escapades. High fences and hedges hid intimate rendezvous, the innumerable halls, hidden doorways to bedrooms were places for secret and exotic pleasures.

The 18th century saw Rococo art, an unadulterated celebration of the glory of nature, providing a platform for a sexual revolution, taking its lead from earlier Renaissance Roman iconography. Literature, drama and art were awash with tales of unfettered carnal pleasures and adventure, all converging to be a late 18th century all-out assault on the senses.

Particularly France, the superpower of the day, saw its extreme wealth focussing first and foremost upon ‘play’. Following his father’s strict reign, Louis XV ripped open the bulging corset that reined in aristocratic French society and what spilled out was a feast of flesh, fantasy and exuberance.

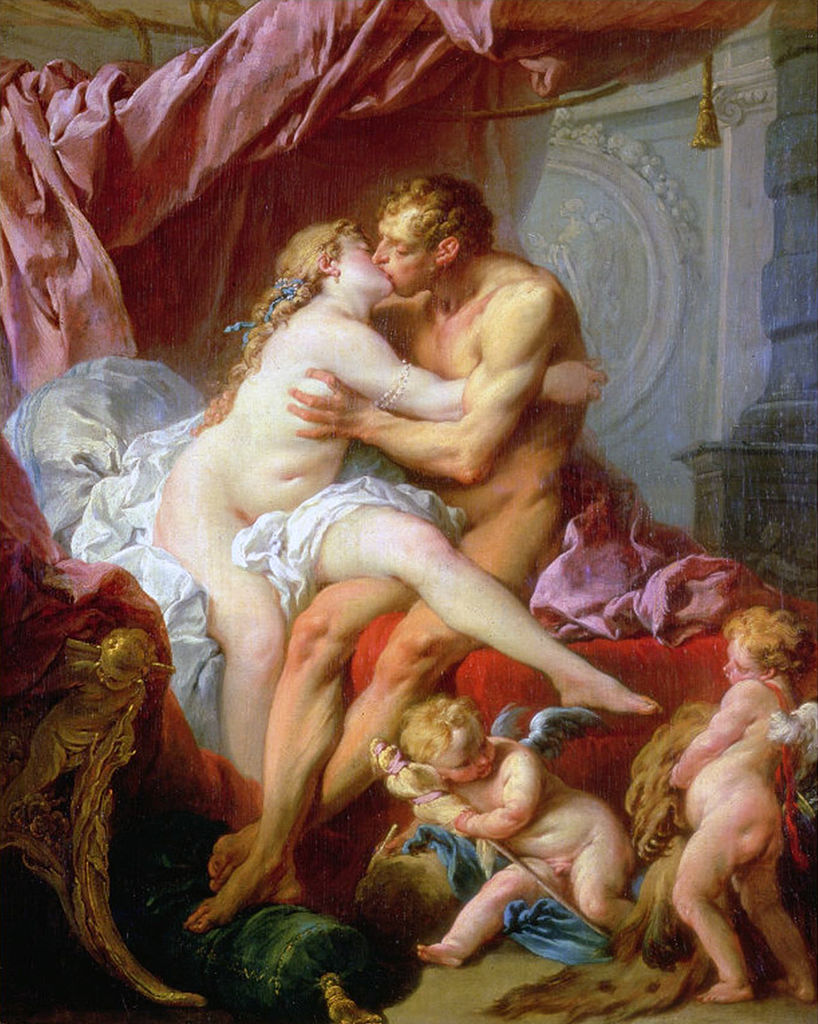

France was now the undisputed all-powerful nation of the 18th century, having succeeded Italy as the arts and cultural leader of Europe. A small armoury of artistic musketeers would dominate 18th century French artistic taste and becoming the emissaries of erotica. Francois Boucher was a French painter renowned for his lavish and luxurious paintings of paradisal landscapes and decorative allegories, abundant with nudity. Nature, now tamed, was the backdrop to vast compositions of delightful rustic and rural scenes populated with glowing and voluptuous shepherdesses and milkmaids. Boucher would also use the classical tales, allegories of Cupid, Venus and lovers, half-dressed among the ruins of an ancient world. Boucher is best remembered for his Odalisque works depicting in the same voluminous, fleshy style, but overtly sexual. His conventional work The Breakfast (1739) records his wife and family dining in their grand drawing room, while in his painting The Brunette the fleshy female subject spreads herself provocatively across a luxurious bed of silk cushions (interestingly the luscious model this time was his wife, too). Boucher relied on patronage, and The Brunette was a commission from the king, who evidently also had a penchant for debauchery.

Boucher would paint seven portraits of the king’s mistress, Marquise de Pompadour. She effectively managed the cultural affairs of France for the king, from his choice of artists to his taste in architecture, porcelain and literature. She fervently promoted Francois Boucher’s works (although he never seemed to have painted her in an erotic style). Boucher was prolific, a veritable semi-private soft porn factory for the insatiable French establishment. Boucher’s vast output swings from the cheesiest winter woodland scenes – with just a hint of intrigue – to the polar opposite as seen in the blatant bestial and vaginal voyeurism of his rendition of the classical tale of Leda and Swan. Patrons could have their naughtiest paintings accessorised with curtains or even commission double-sided pictures for immediate reversing (should mother dearest be visiting).

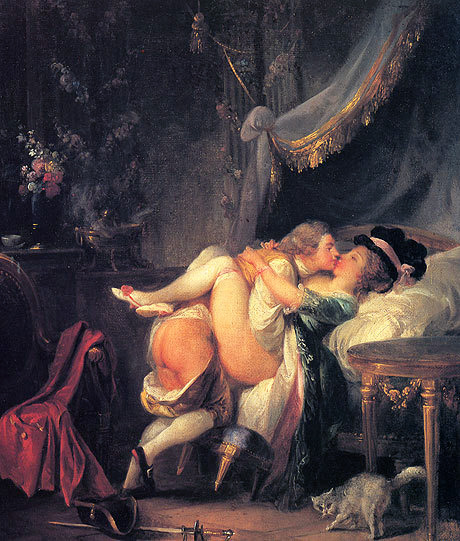

Boucher has several pupils who became successful in their own right, such as Pierre-Antoine Baudouin, who actually married his master’s beautiful younger daughter and model Marie-Elisabeth. Baudouin, who was known as a bit of libertine himself, focused his attention on the French boudoir and what went on behind its doors. It’s rumoured that his early death was the result of “libertinage”.

Hot on the heels of Boucher was Louis-Léopold Boilly, who moved to Paris in 1785 and made a name for himself as a painter of mischievous images. At the height of his popularity, his painting “Two Young Women Kissing” elicited accusations of obscenity. Facing prison, he changed direction and turned his attention to Parisian salon life as his preferred subject.

Perhaps the best-known musketeer of the French hedonistic party was of course, Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732 – 1806). Fragonard produced more than 550 paintings and in addition many drawings and etchings, but his earthly sexual imagery is subtle, with eroticism implied rather than drawn or painted, as opposed to the blatant detailed sexuality of Boucher.

The Swing (1767) portrays a delightful girl flying through the forest, legs flaying, skirts billowing, perhaps offering a tad too much. Vast dynamic compositions of exploding colours in lush arcadian landscapes, these splendid settings play out the dramas, intrigues and liaisons of a gorgeous and carefree elite.

Finally, there was Jean-Frédéric Schall, another French painter who was one of the last important artists to contribute to the “fête galante” (courtship party) style pioneered by Antoine Watteau. Schall had two personalities as an artists – so many of his small-scale works depict seemingly innocent maidens frolicking through idyllic settings à la Watteau, but he also liked to heat things up on the canvas…

The French Ancien Régime revelled in this artistic sexual soup, from intrigue to intimacy, the public works disguised as classical subjects, the private collections displaying blatant voyeurism. However, that all came to a sudden and bloody halt with the storming of the Bastille on 4th August 1798 and the French Revolution. The artists’ patrons were now literally headless, as was the artists’ cultural direction.