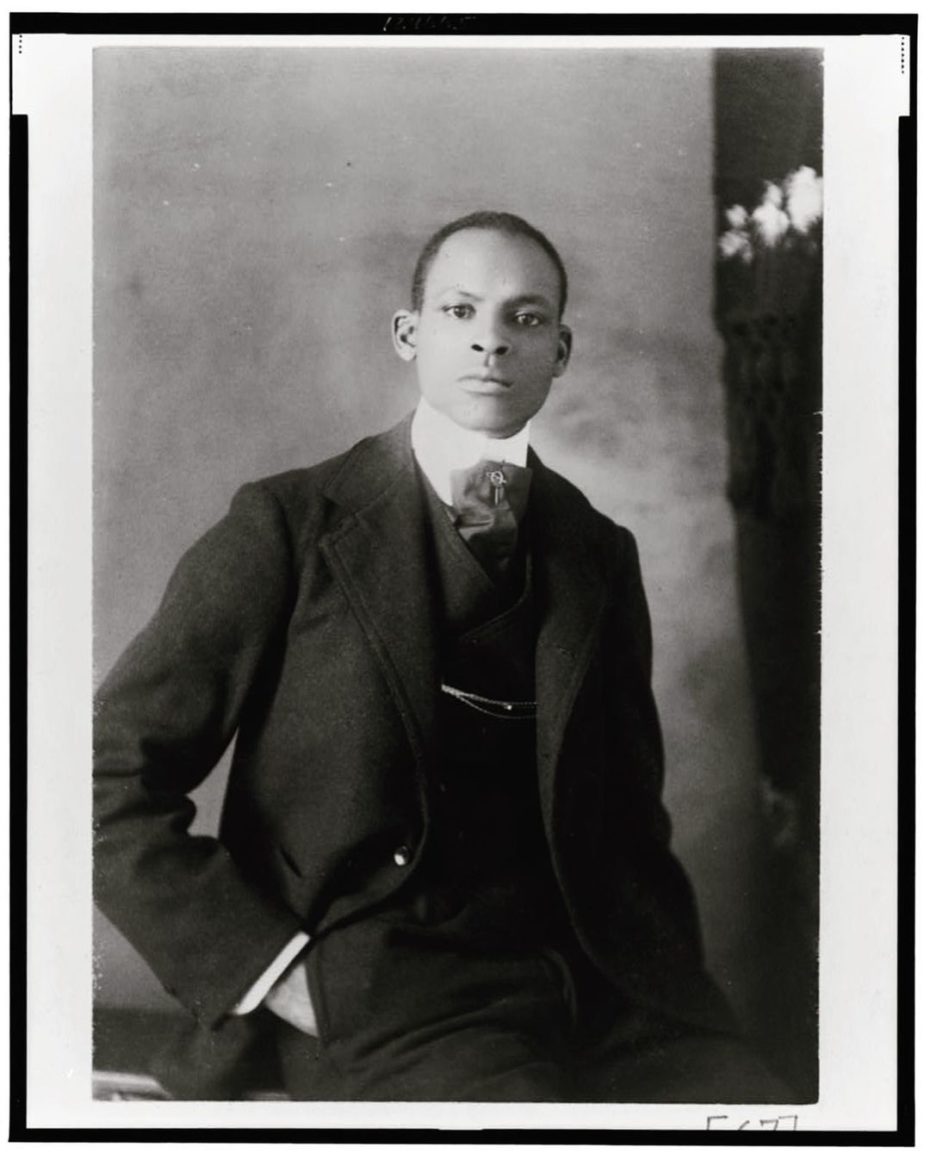

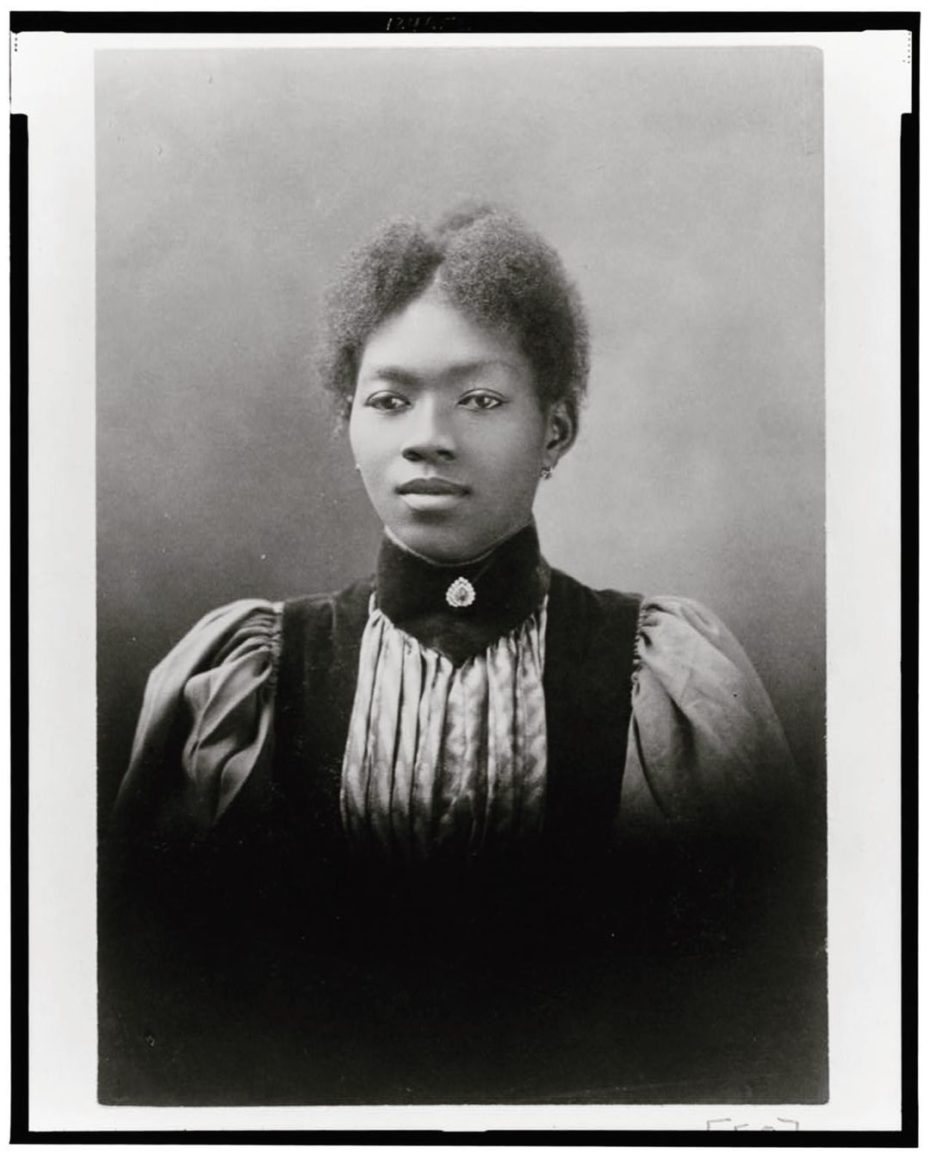

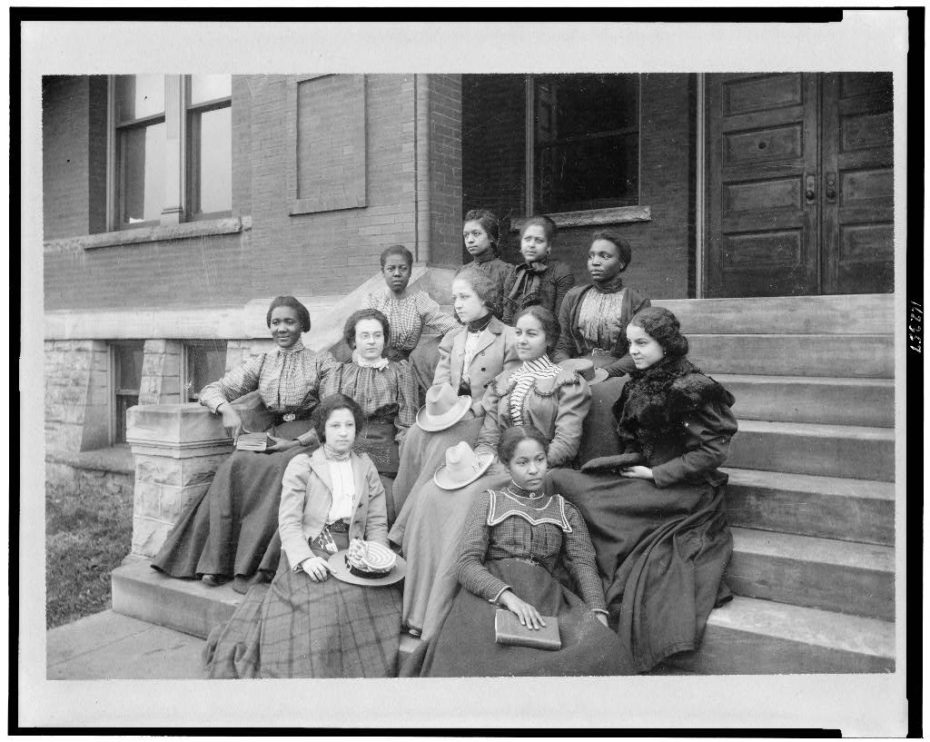

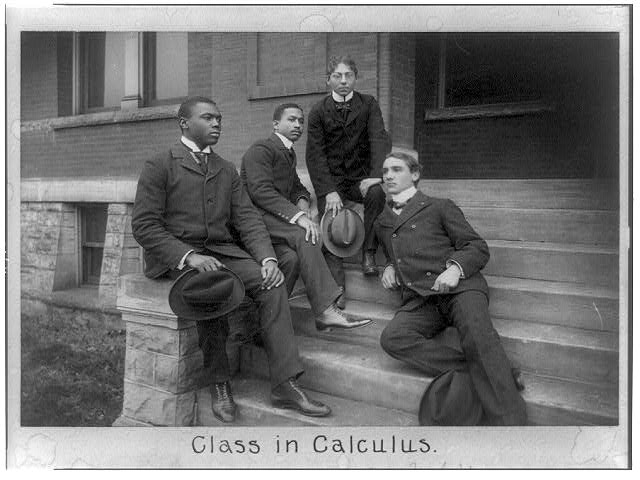

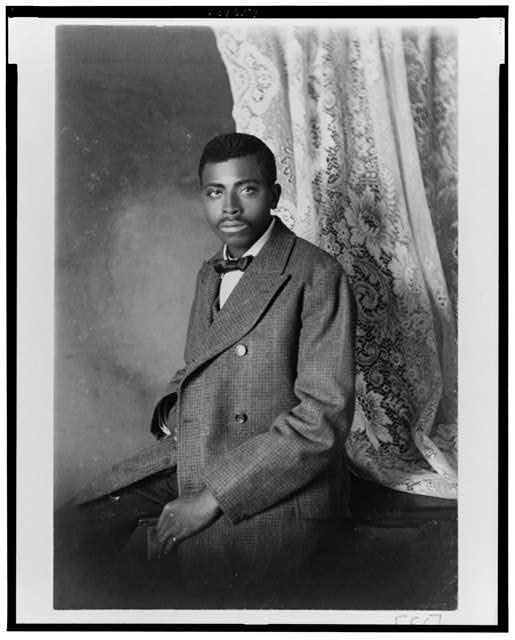

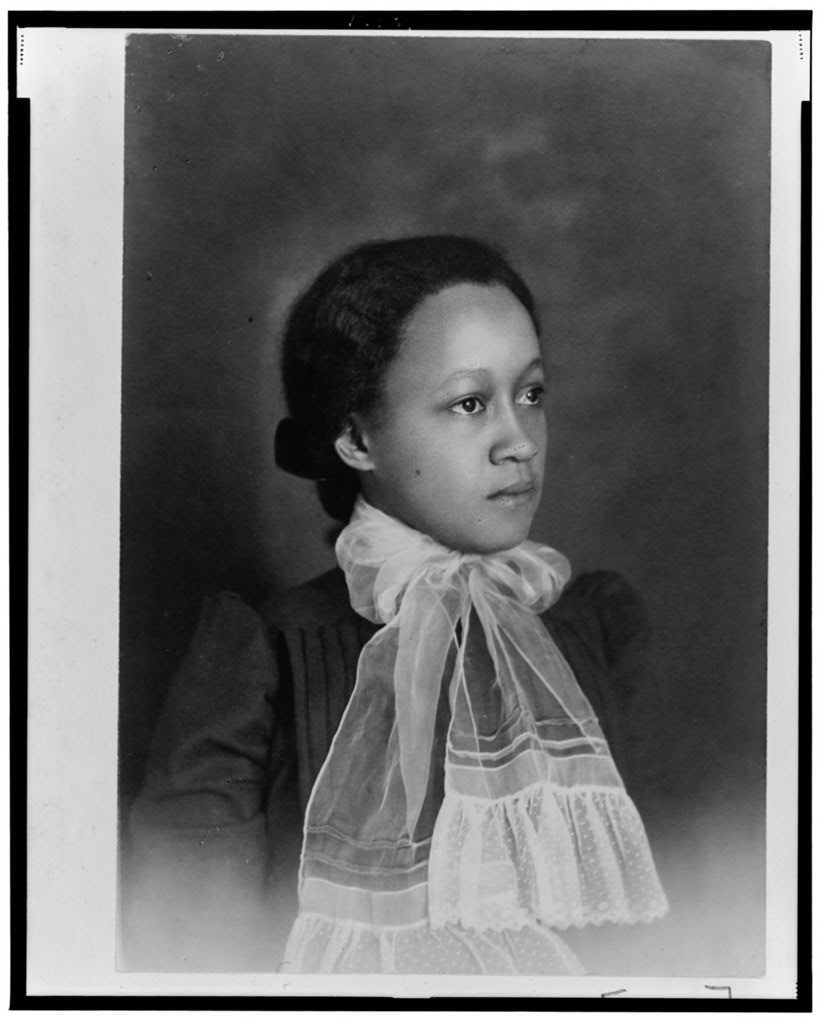

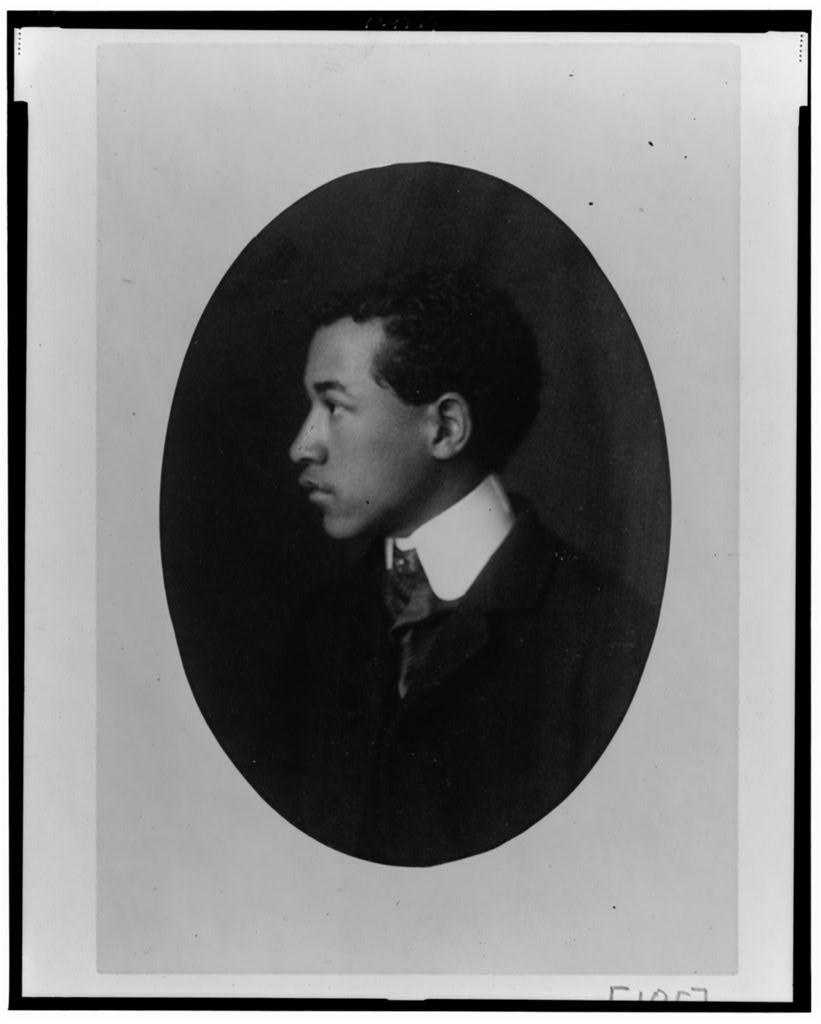

These are the the face of stylish young African American women and men at the dawn of the 20th century. At the time, only 37 years after the end of slavery in the United States, Jim Crow was more than a series of rigid anti-Black laws, it was a way of life in America. But across the ocean in Paris, at an exhibition that would mark the new century, these faces represented a different way of life….

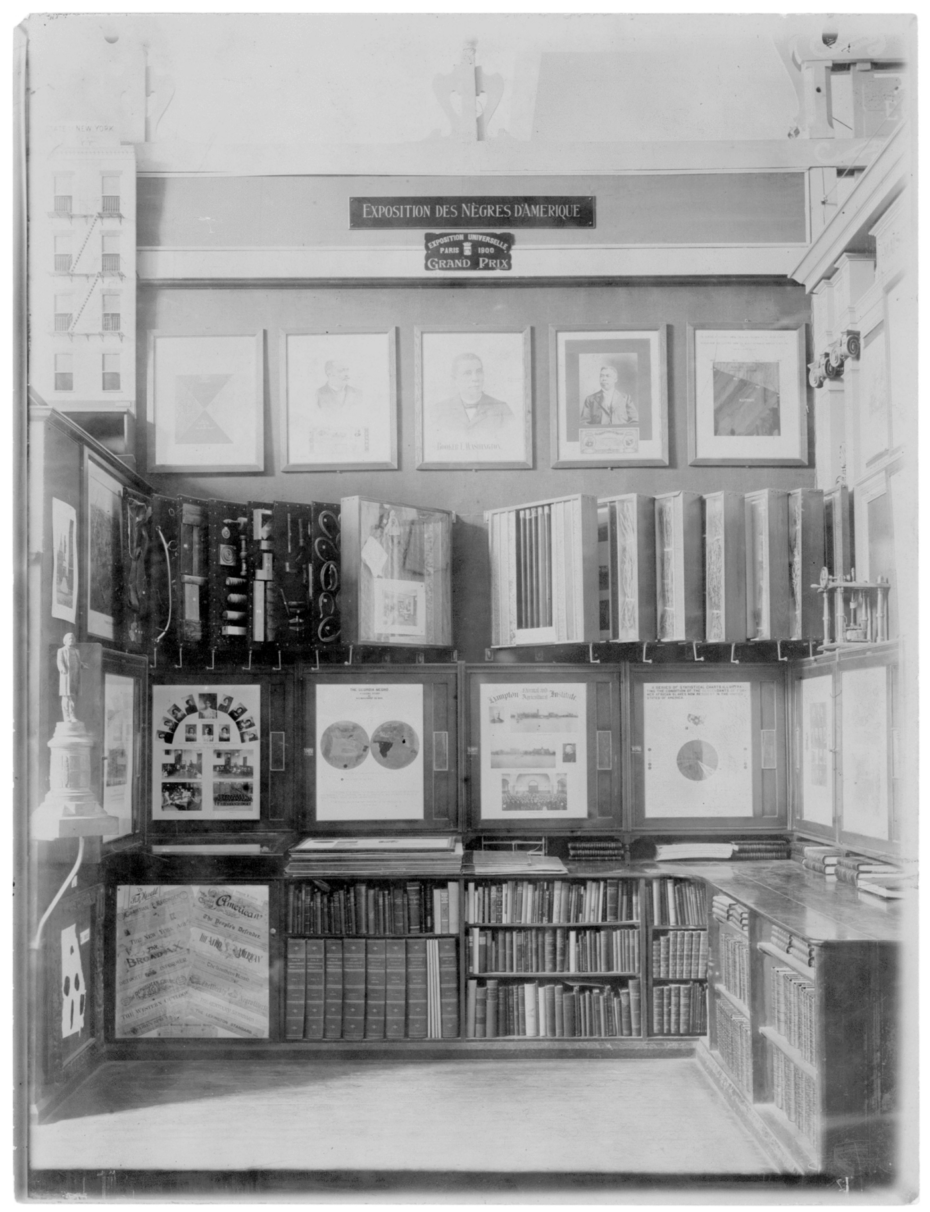

“On the banks of the Seine, opposite the Rue des Nations,” began the esteemed sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois in an essay titled The American Negro in Paris, “stands a large, plain white building, where the promoters of the Paris Exposition have housed the world’s ideas of sociology. As a matter of fact, any one who takes his sociology from theoretical treatises would be rather disappointed at the exhibit; for there is little here of the “science of society” […] In the right-hand corner, however, as one enters, is an exhibit which, more than most others in the building, is sociological in the larger sense of the term … This is the exhibit of American Negroes, planned and executed by Negroes…”

Du Bois was writing in the November 1900 edition of The American Monthly Review of Reviews about a sociological display he had helped produce within the Palace of Social Economy at the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris. The exhibit was a joint effort between Du Bois, the lawyer Thomas J. Calloway, and the Assistant Librarian of Congress at the time, Daniel Murray. Its purpose was as Du Bois said – a means to demonstrate and commemorate in a systematic manner, the lives of African Americans at the turn of the century. A carefully thought-out plan, the exhibit would look at the history, present condition, education, and literature of a group of Americans that now numbered not in the thousands, but the millions.

Du Bois is the name most associated with this groundbreaking exhibit, but it was African American lawyer and educator Thomas J. Calloway – an old classmate of Du Bois’ at Fisk- who really got the ball rolling on the project. He sent letters to more than a hundred African American representatives from across the United States – including Booker T. Washington, famed orator and adviser to several US presidents, to ask for help in advocating for an exhibit he had in mind for the world’s fair that was about to happen in Paris.

What exactly Calloway had in mind was a display – outright proof, even – of the possibilities of the common African American man, woman, and child. And he was going to get it. Washington personally appealed to then-President William McKinley, and with just four months to go until the fair’s opening, Congress allocated the exhibit $15,000 in funds. With some money in the bag, Calloway turned to his old friend Du Bois – no longer his classmate but a noted sociologist, historian and civil rights activist – and Murray, who was Assistant Librarian of Congress, to crack on with assembling materials. They were on their way.

Born in 1868 in Massachusetts, Du Bois first attended Fisk University, a historically black college in Nashville, Tennessee. After receiving a bachelor’s degree from Fisk, he went on to Harvard (who didn’t accept course credits from Fisk) where he would later become the first African American student to gain a PhD from the college. 1892 saw him receive a fellowship from the John F. Slater Fund for the Education of Freedmen, enabling him to attend the University of Berlin for graduate studies, and it was there that he would come of age intellectually, as well as travelling extensively across Europe. Of his time in Germany, Du Bois remarked, “I found myself on the outside of the American world, looking in. With me were white folk – students, acquaintances, teachers – who viewed the scene with me. They did not always pause to regard me as a curiosity, or something sub-human; I was just a man of the somewhat privileged student rank, with whom they were glad to meet and talk over the world; particularly, the part of the world whence I came.”

A few years after his return to the US, he took up a professorship in history and economics at Atlanta University – another historically black institution. It was here that he would complete the first scientific study of African Americans in his 1899 book The Philadelphia Negro, marking a major contribution to early scientific sociology in the US. Du Bois was prodigious at Atlanta, producing papers, hosting conferences, and receiving several government grants to continue his work. But what did his students make of him? Apparently, they generally considered him brilliant, if somewhat aloof. And strict.

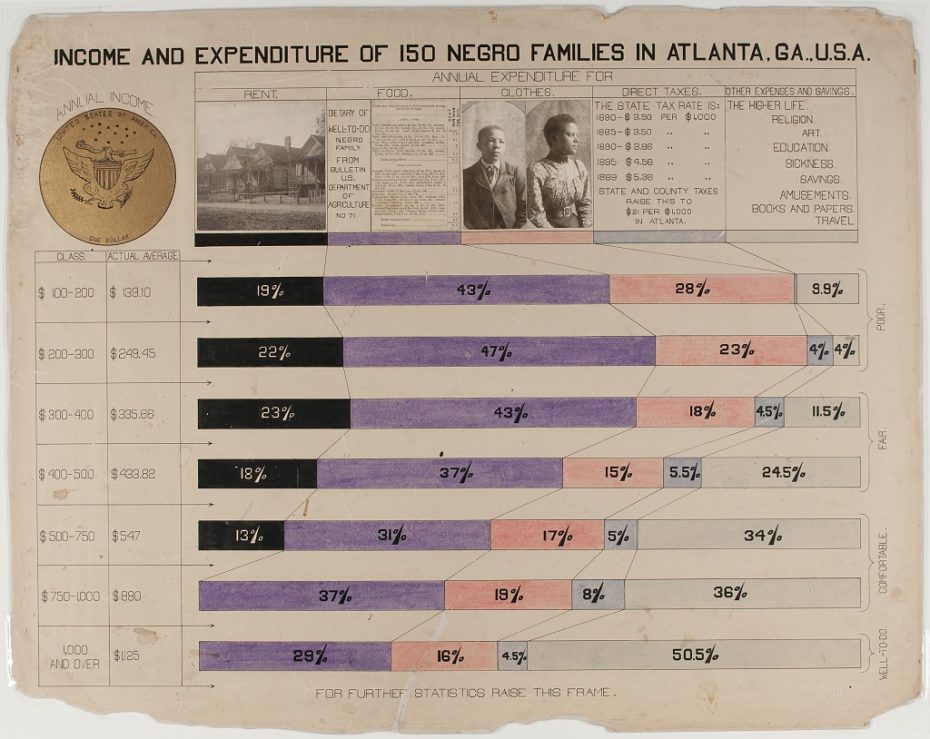

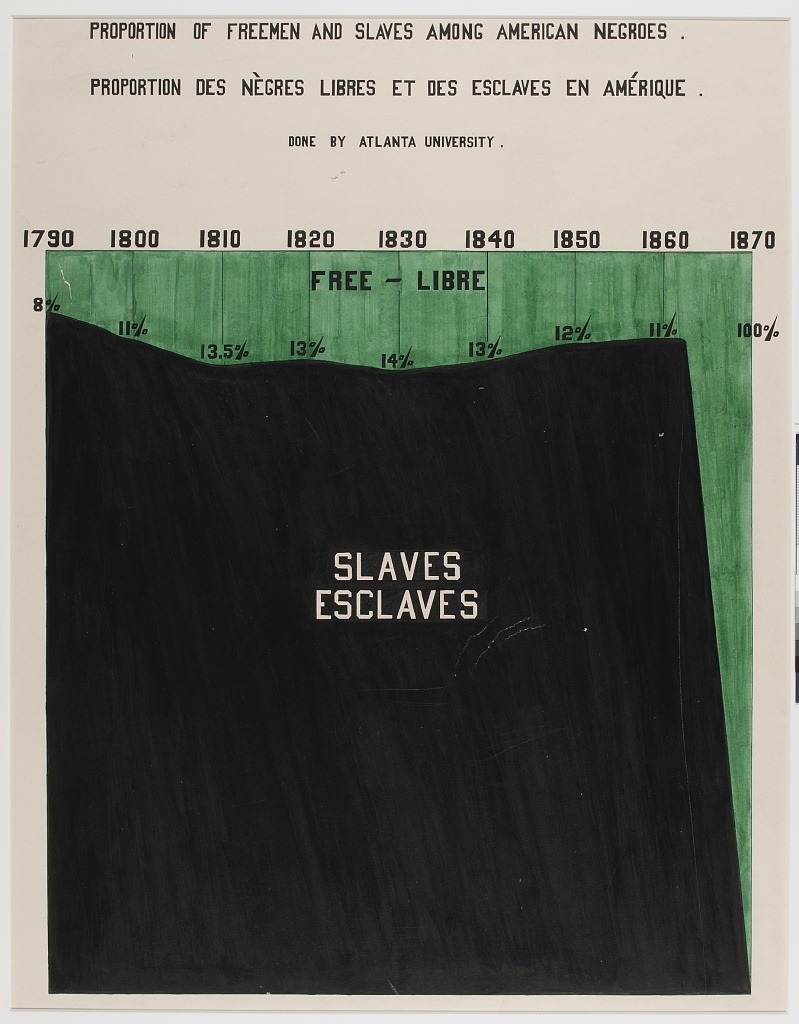

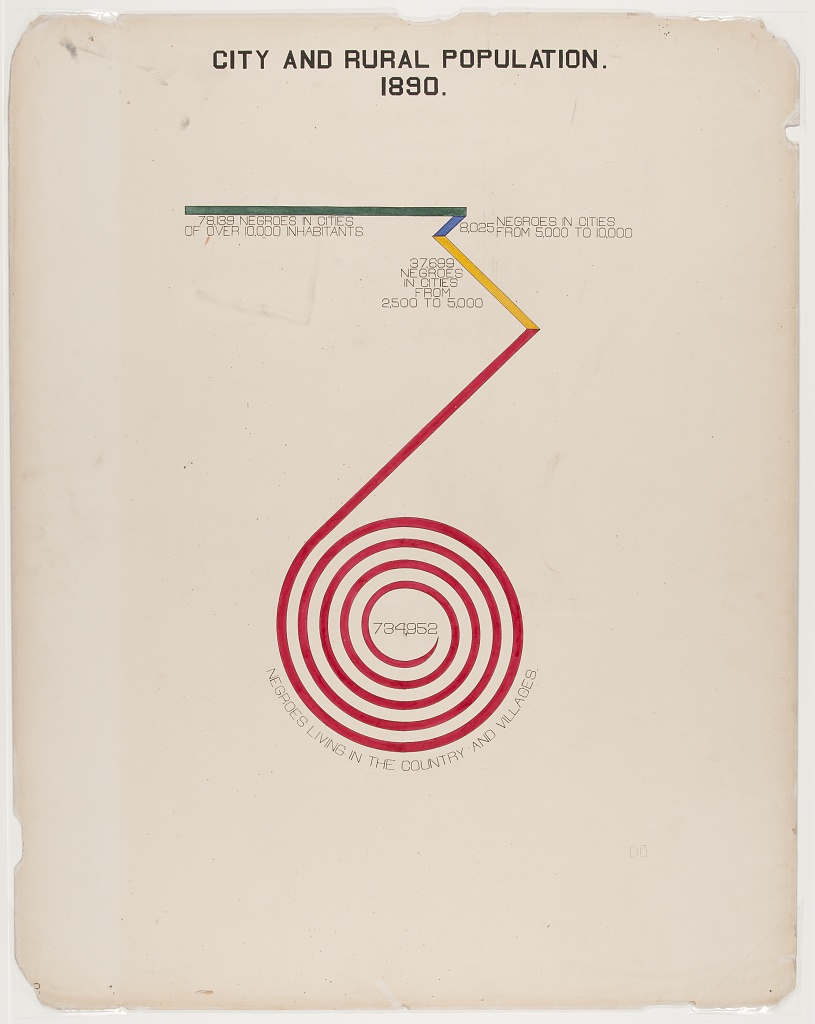

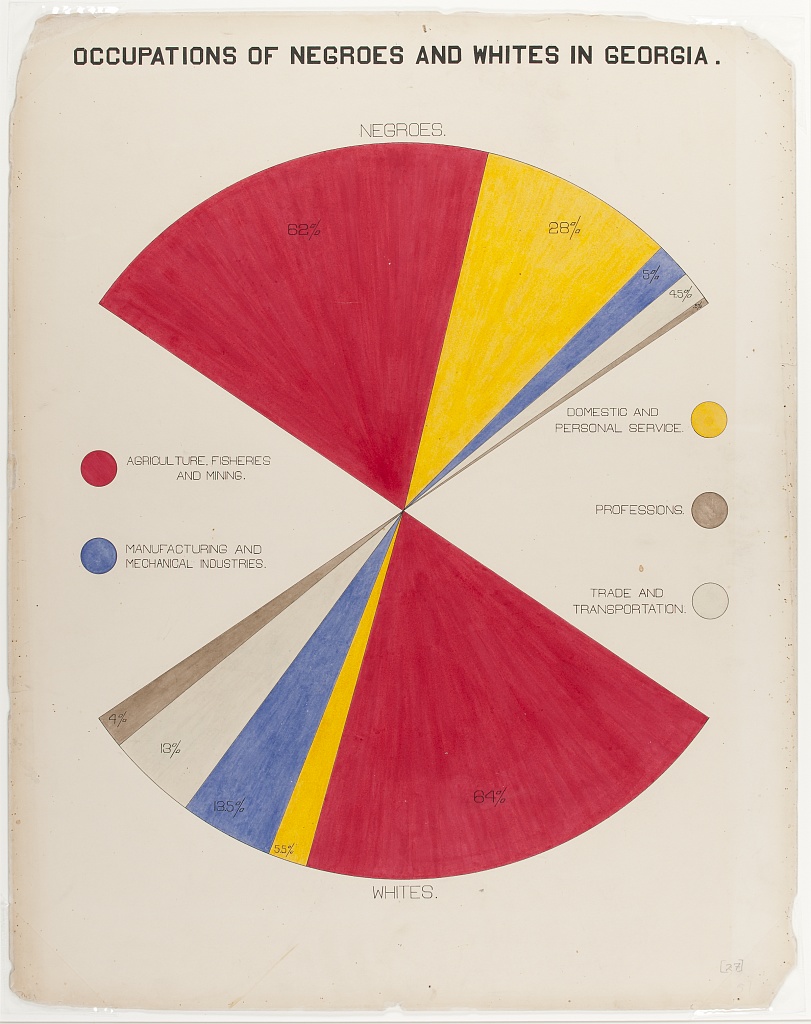

It was these Atlanta students that would go on to help produce one of the most important aspects of the exhibit – data visualisations of a sociological study carried out in Georgia, a more minute, localised version of the larger national study that was also produced. Georgia was not only a convenient choice, being the state in which Atlanta university is based, but also a very useful one: Du Bois was the first to admit that conditions in the Southern state were not rosy for African Americans, but an awful lot of them lived there, more than any other state, in fact.

Du Bois and his students developed a set of strangely beautiful data visualisations; hand-drawn lines and hand-lettered titles in pie-charts, bar charts, and maps, in order to demonstrate changing socioeconomic levels experienced by African Americans. But these data visualisations were not a particularly scientific attempt to present data, methods Du Bois was far more used to in his painstaking work, but rather an attempt to tell a story, a compelling narrative crafted to sway minds and influence social change. Each data set was a unique rendering in graphite, watercolour, and ink – not a mechanical print – and was titled in both English and French to ensure that the local literate population could comprehend the information. Du Bois was well aware of what an opportunity this was, and took every step to make sure they utilised it to its fullest.

One of the more well-known data sets is a mirrored fan chart of Du Bois’ own design, deceptively simple in its execution. Displaying corresponding categories, it allowed for the direct comparison between the occupations of African Americans and whites, an event horizon across the line famously referred to by Du Bois when he made the resounding declaration that “the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the colour line.” What was so striking about this data set was the differences in occupation between the two groups, or rather the lack of it. In fact, the only real contrast to be found is that between those in domestic and personal service, a role largely held by women, a data set like this brings to mind the words of Malcolm X, speaking some six decades later, decrying the Black woman as the most disrespected in America.

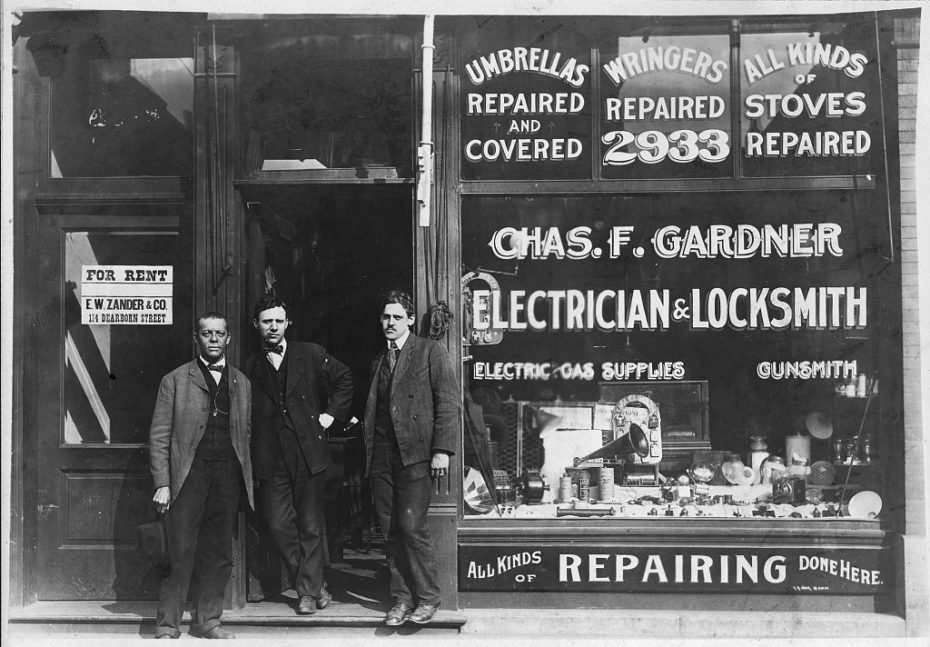

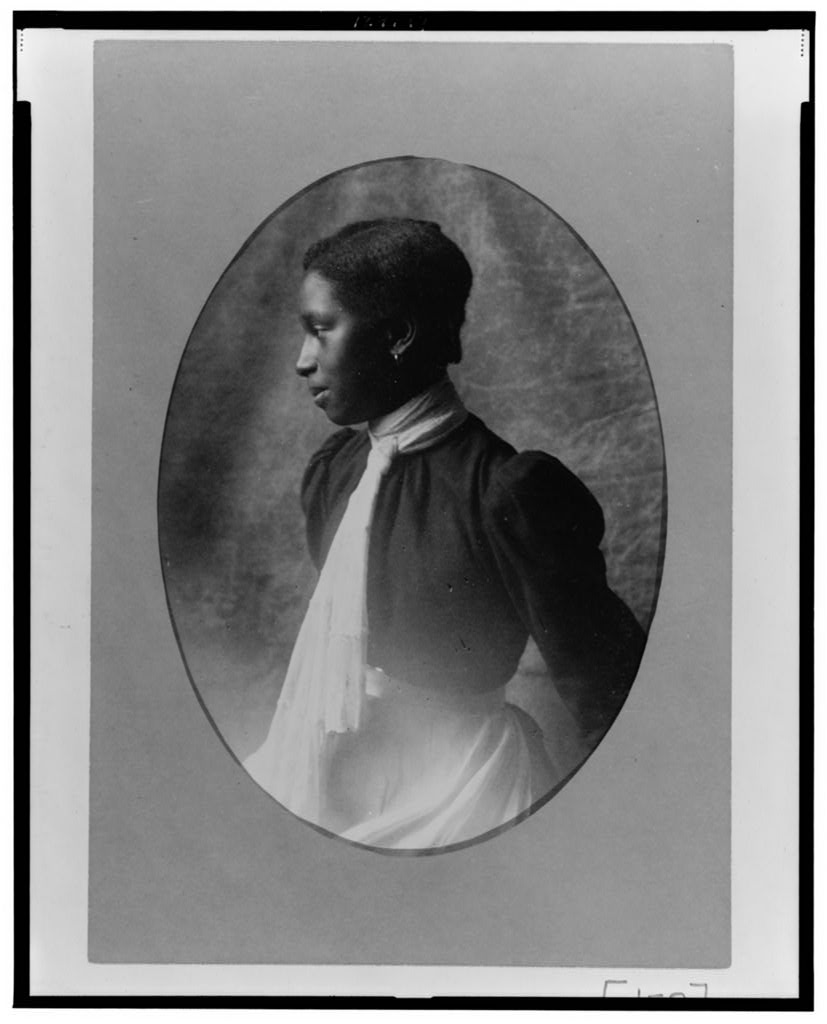

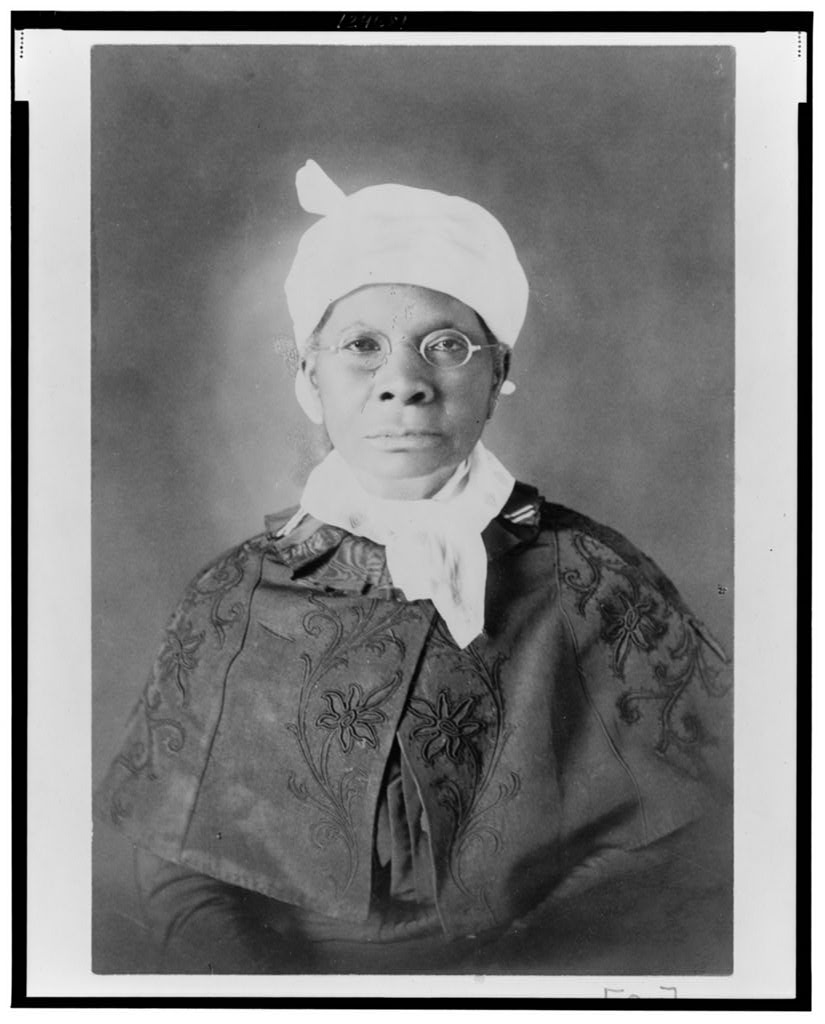

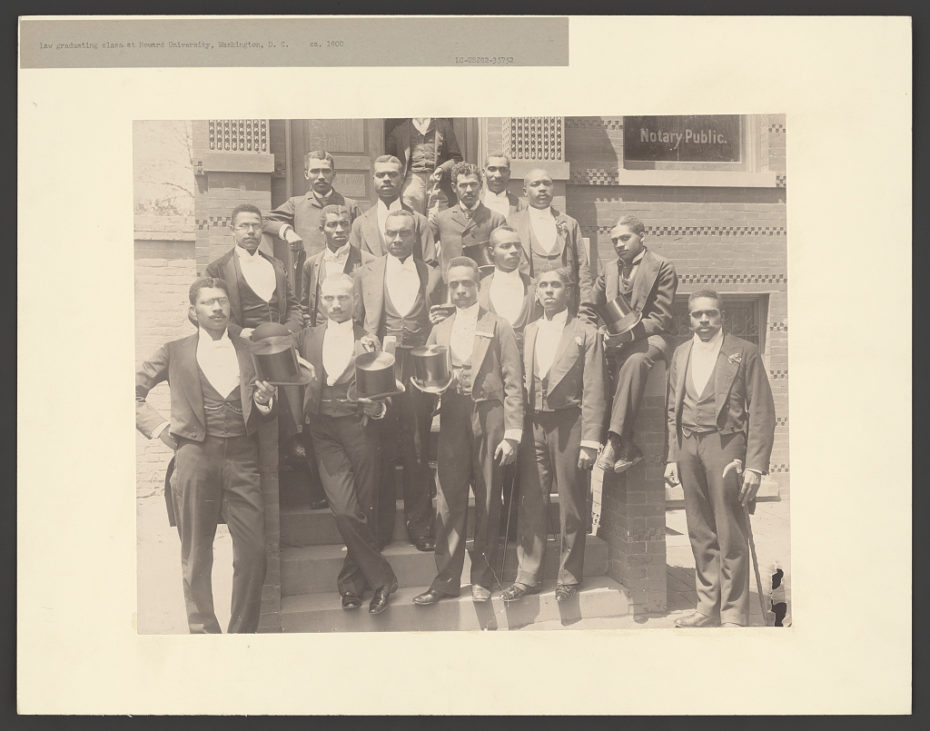

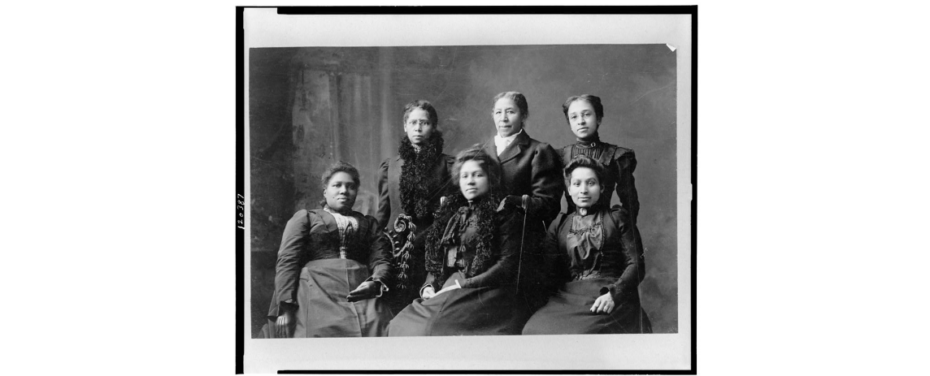

But it wasn’t all about the data. What the exhibit wanted to do, its most vital job really, was to extend that data; contextualise it. What did this data look like off the paper? What did it look like in the great, big out there? This was where the everyday African American came in, whether they were student or shopkeeper, seamstress or senior clerk. Alongside data visualisations, Du Bois compiled hundreds of photographs of African Americans at work and at play; in other words, at life. Many of these photographs were taken by Thomas E. Askew, who often documented prominent members of the African American community in Atlanta.

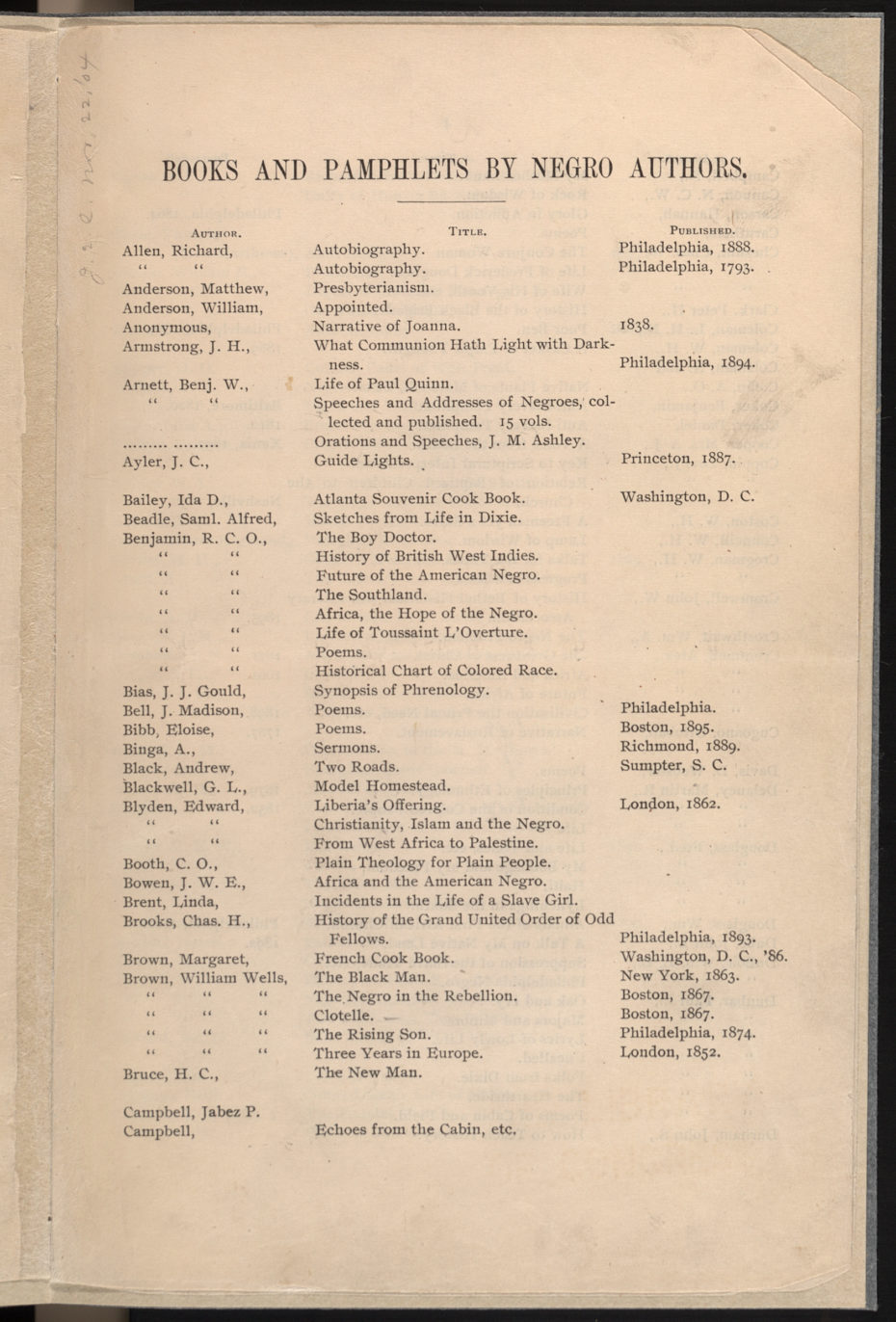

Murray, in his position as Assistant Librarian at the Library of Congress, was able to lend further credence to cultural contributions being made by African Americans in the form of books, pamphlets, and newspapers. Murray was a strong believer that “the true test of the progress of a people is to be found in their literature.” He appealed to the public to submit examples for inclusion in the exhibition, and compiled a catalogue of works – from autobiographies to poetry to cookbooks. In total, 1400 titles were featured. This account was a point of particular importance to the exhibit, as Du Bois noted in The American Negro in Paris, “The development of the Negro thought — the view of themselves which these millions of freedmen have taken — is of intense psychological and practical interest.” Following the exhibit, the catalogue was placed in the Library of Congress as part of its collections.

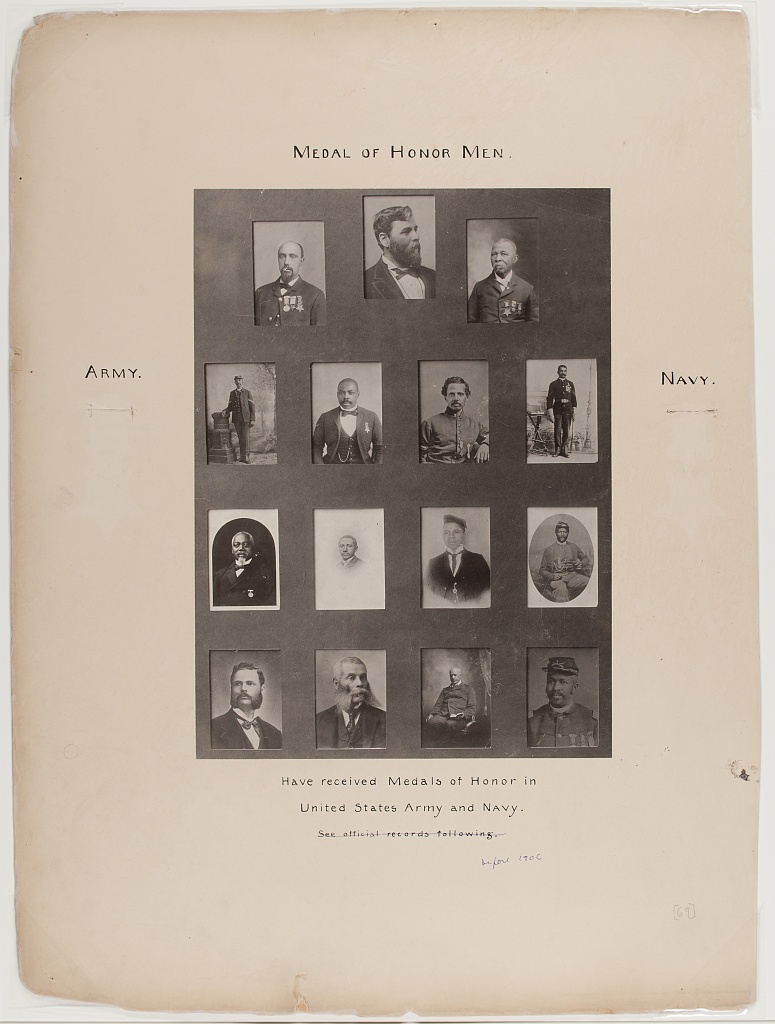

All in all, alongside Murray’s bibliography, the exhibit featured some five hundred photographs, many of them Askew’s; four bound volumes of nearly 4000 official patents made by African Americans; 32 handmade graphs and charts, as designed by DuBois for his Georgia social study, and a further 30 statistical graphics on the African American population at large. There was even a statuette of Frederick Douglas. But perhaps some of the most striking inclusions were the records of African American servicemen from the army and navy, many of which carried Medals of Honor, and the 400 pages of The Black Codes that Du Bois personally hand-wrote.

The exhibit remained in place for the duration of the Paris fair – from April to November, during which over fifty million people passed through. The group’s work did not go unnoticed, if not perhaps noticed as much as it should have, or as much as Du Bois aspired for it to be. In his book A Small Nation of People, Pulitzer prize-winning scholar David Levering Lewis wrote of their effort: “The Negro exhibit at Paris was a racial imperative, a momentous opportunity and obligation to set the great white world straight about Black people.” Not a small task, then. And did they achieve it? Well, that’s hard to measure.

The exhibit itself was recognised by judges, who awarded it several prizes, including an overall Grand Prix and, for Du Bois himself, a gold medal. And the African American press, outlets like The Coloured American, were ecstatic. The European media, on the other hand, were more moderate in their praise, and largely congratulated it on its small part in the larger exposition as a whole. The White American press ignored it entirely. In his comprehensive account in the North American Review, the US commissioner-general failed to mention it. Of all the reactions Du Bois could have hoped for, the very last was indifference.

Upon his return to the US, there was a certain disenchantment between DuBois and the social sciences that had driven so much of his work. Later in his life he would reflect on this change, writing, bleakly, “So far as the American world of science and letters was concerned, we never ‘belonged’; we remained unrecognized in learned societies and academic groups. We rated merely as Negroes studying Negroes, and after all, what had Negroes to do with America or science?”

But there was success still to come for Du Bois, if perhaps of a different kind. Three years after Paris, he published The Souls of Black Folk, a book that combined African American culture with current events. After his data visualisations failed to make their mark, he struck a deliberately unscientific tone here, using fragments of African American spirituals instead of hard statistics. And it worked. The book’s emotional rather than academic appeal drew in a larger, global audience of readers.

In recent years there has been renewed interest in what Calloway, Du Bois and Murray set out to do with their exhibit. Harvard hosted a symposium to discuss Du Bois’ impact on sociology, with lectures and panels retracing the methodical practices of his work. In 2020, interdisciplinary artist Jina Valentine developed The Exhibit of American Negroes, Revisited – a simple but significant attempt to reveal “patterns, progress, and impasses in the socioeconomic development of Black Americans over the past century.” The series of works updated the original 67 data sets created by Du Bois with contemporary data on the lives of black Americans in 2020. Today, the Exhibit of American Negroes is housed at the Library of Congress.

Back in 1900, the exhibit had not produced the desired impact but Du Bois, rounding up his reflections on the attempt in The American Negro in Paris, considered what they had managed to create: “We have thus, it may be seen, an honest, straightforward exhibit of a small nation of people, picturing their life and development without apology or gloss, and above all made by themselves.”