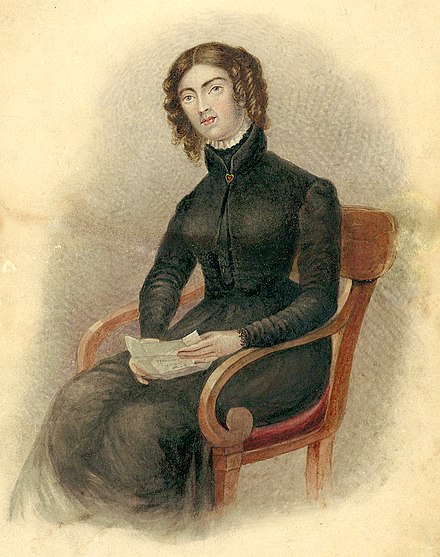

Anne Lister has recently crept out of the shadows of what was her own gothic novel, penned almost two centuries ago. Like all things of the neo-Gothic late 18th century, hers was also a world of shadows, veils, intrigues and most of all, it concealed her obsessional love for other women. British society was at a tipping point, caught between the crumbling old world of castles and cathedrals and the harsh reality of the new industrial age of factories and finance. Society was restless, creaking and cracking at the edges to contain centuries of repressed anxieties and entrenched attitudes. Anne Lister, regarded as ‘the first modern lesbian’, was fighting to get out.

A time of great change, Britain’s 18th century’s industrial revolution was running in top gear. The old rural conservative culture was waning and where once tall trees grew, factory chimneys reached ever higher. Little hamlets became towns, towns mushroomed overnight into grimy cities. Much of the north of England morphed into an unforgiving and desolate engine house for the British Empire. New cities Manchester and Leeds literally consumed the dark forests, green fields and dipping dales around them. Some of the old country estates clung to their green patches, now as refuges, amid the cancerous urban spread. Money had moved to city commerce and urban industry, old values faded, new ones emerged. The 18th century had also seen a sexual revolution of free-spirited libertines with their sex clubs, hot literature and erotic art. Everything was questioned, much was yet to be explored.

Anne Lister was born into this maelstrom of change at Shibden Hall in 1791, a modest old 15th century house and landed estate that had grown piecemeal over the centuries. Like a description from a gothic novel, this rambling crooked house sits in the rolling, if sometimes bleak and windswept, Yorkshire dales. Anne lived at Shibden from the age of 24 with her unmarried and ageing uncle and aunt. Shibden became her fiefdom and private world. From the outset of her stay, Anne had authority over the estate which, only two years later in 1826, she inherited on the death of her uncle.

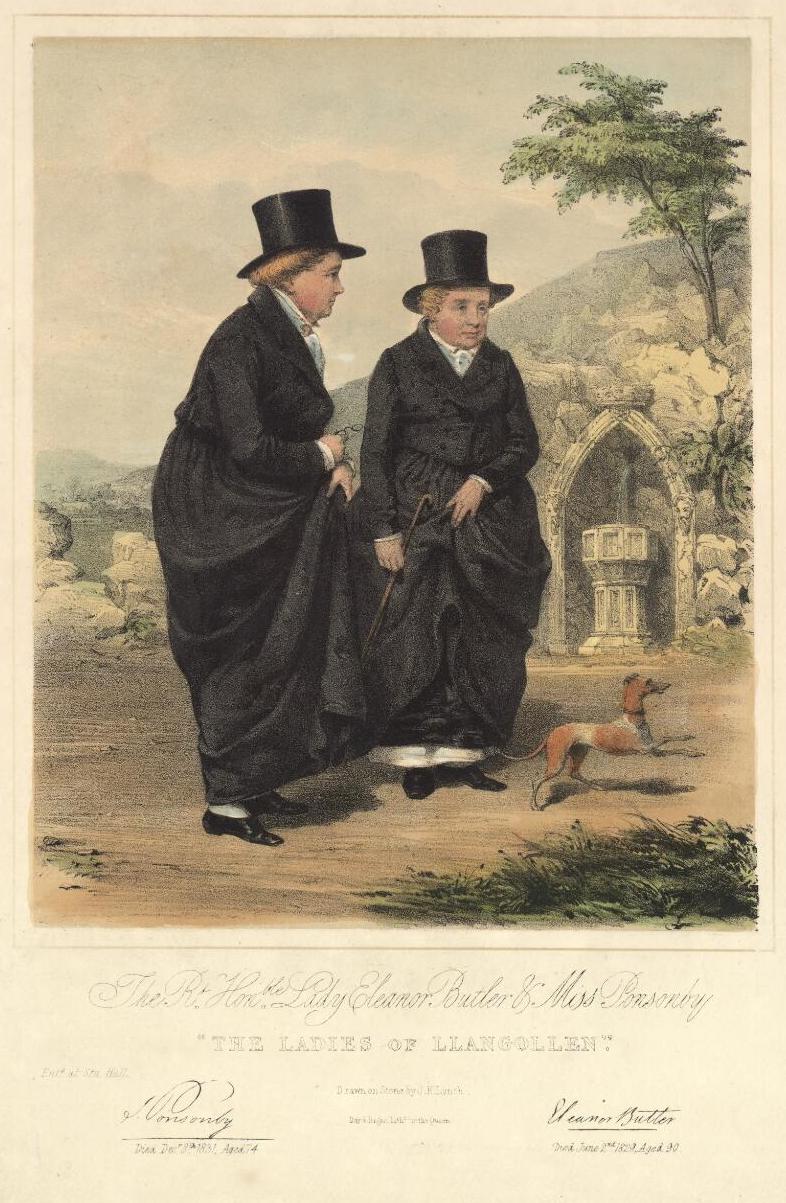

In 1822, a 23 year old Anne visited the then scandalous ‘Ladies of Llangollen’, Lady Eleanor Butler and Lady Sarah Ponsonby. Both aristocratic women had fled Ireland under pressure to marry, to a quaint and quirky little gothic fantasy lodge at Plas Newydd in Wales. The ladies lived together and entertained intellectuals and free thinkers of the day at their little folly. Their guests including the likes of Shelley, Byron and Wordsworth; the latter would write a sonnet about them. The ladies were clearly more than just good friends, they were sexually active lovers who had participated in a ‘marriage ceremony’ of sorts in church and exchanged vows and rings. Anne was captivated by the joy of the pair’s unconventional relationship, which she would recount with enthusiasm and rapture in her diaries.

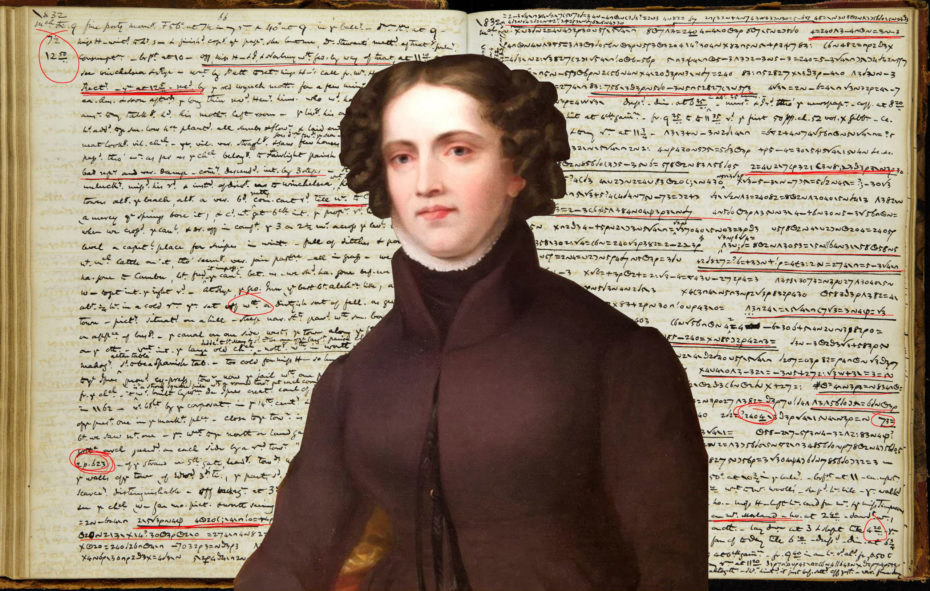

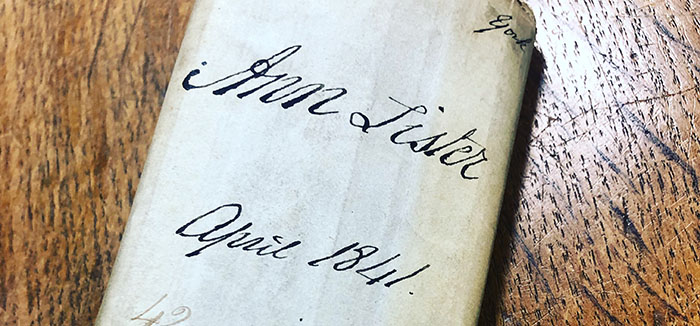

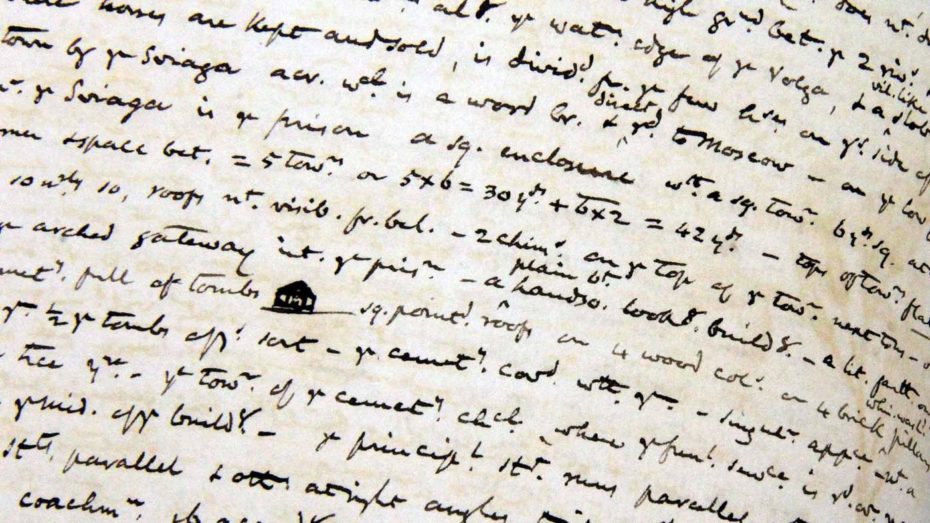

Anne’s enduring legacy was her vast output of 26 volumes of explicit diary entries. The diaries spanned the period from 1806 to 1840, with 5 million words and symbols compulsively recounting everything in her daily life – from mundane household tasks and commentary on the countryside to amorous encounters. Much as the ladies of Llangollen had done – to avoid society and forever having to engage with mixed company and the risk of marriage, Anne would lock herself away with pen and paper at Shibden.

She wrote obsessionally of her lovers and romantic encounters. Her diaries recount how she planned and executed the seductions and captures and give us intimate detail of how she devoured her ‘prey’ in bed. A ream of conquests were revealed in the diaries: Eliza Raine was Ann’s first lover at the age of 13 when they had shared a school dormitory room, Isabella Norcliffe was next, an heiress who would never marry, but was a little too fond of wine for Anne’s taste! Marianna Lawton was the love of Anne’s life, but also broke her heart when she eventually married, a man no less. Ann’s lasting relationship was with Ann Walker, also an heiress and business owner, to whom she got engaged and they regarded themselves as married. They both lived at Shibden Hall, managed their businesses and travelled together until Anne’s premature death at the age of 49 on one of these trips.

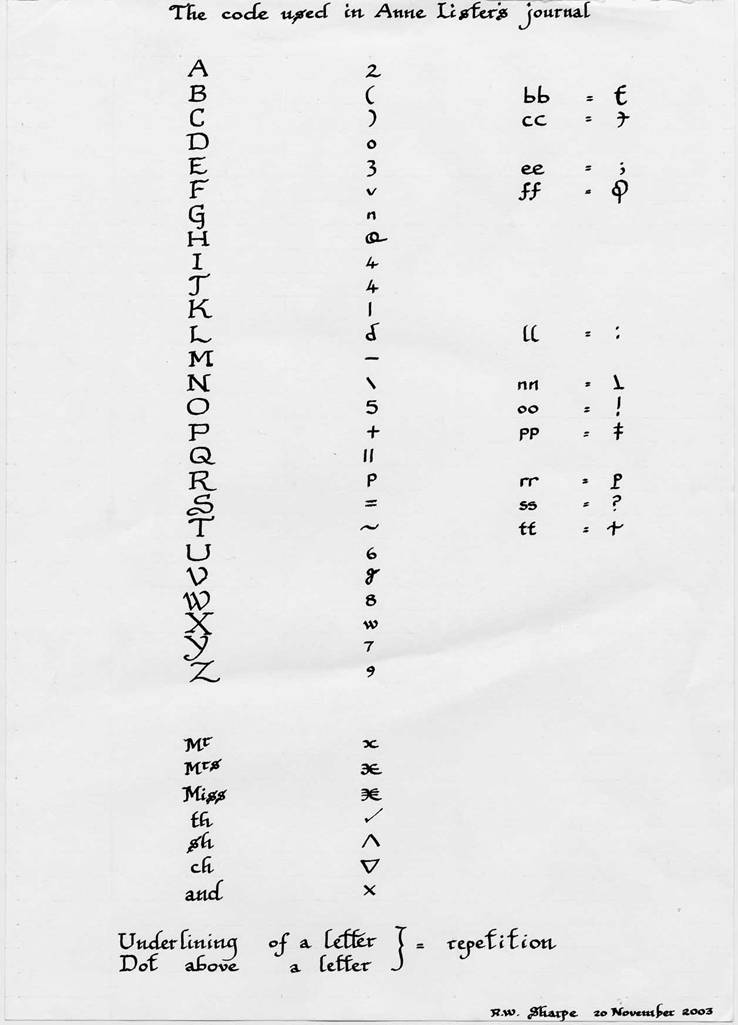

Society at the time wouldn’t take kindly to the lifestyle Anne would pursue however, so secrecy was paramount. To conceal her diarised deepest and darkest desires and deeds, Anne needed code: she invented new words, used alternative alphabets and created unique graphic symbols for her pages. Paragraphs might start in plain English and introduce the new words, then break into cipher alphabets with symbols populating the margins of the pages. Anne felt compelled to record everything, particularly the most intimate details of her sexual activities, whether frantic seductions in the woods or capricious frolics in the bedchamber.

Typical of the lexicon from her coded diaries would be a phrase such as ‘Incur a Cross’ referring to sexual self-gratification, so did ‘by rubbing the top part of queer’. However, she also used the phrase while describing instances where sitting ‘astride’ a bedpost. ‘Queer’ was applied in its traditional use, but also referred to a woman’s vagina. ‘Grubbling’ was used to describe the hands giving sexual pleasure to another woman, while ‘Being Near’ refers to Anne having her ‘queer’ near her lover’s. A ‘kiss’ was thought to mean an orgasm, Anne believed being ‘near’ or a ‘kiss’ was the ultimate sexual connection she could have with her partner. She would also record her partners’ menstrual cycles, describing these as her ‘cousin’ or ‘Monsieur’. For the latter she’d use a symbolic code, often a little doodle-like graphic in the diary margins.

Anne was driven to write this revealing and confessional work throughout her life, fuelled by the desire to relive treasured memories, the titillation of keeping an intimate secret, the sharing of a forbidden truth and the exhilarating thrill of the ever-present fear of exposure. Perhaps not the outwardly hedonistic pleasures of the likes of Byron and the libertines, Anne’s frustrations had to be contained within the shackles 19th century society.

The neo-gothic world of the late 18th century also saw a new world very much created by women for women in the gothic novel. The great female writers had not only promoted themselves, but a new women’s realm. Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Charlotte Lennox’ The Female Don Quixote typically have women as heroic figures and promoted a fierce female independence. Female fantasy worlds of strong and determined women enduring the windswept moors, clandestine meetings in crumbling abbeys and haunting the gothic piles were the subject matter of the ‘media’ of the time. These women were all sharing an intellectual escapist ‘bedspace’ with the libertine predatory vampire, Lord Byron. No doubt, in this climate Anne will also have felt free to play out her fantasies.

Not unlike a vampire, Anne also existed in two worlds, one of sexual fantasy and another of commerce. Around her, the gentle countryside was rapidly changing, the old estates were literally being undermined for the plunder of coal. Canals and later railways scythed across the land above, providing easier money than the drudgery of farming. Also known as ‘Gentleman Jack’ by society ladies, Anne was commercially astute and considered ‘manly’ in her approach to business. Her empire included shares in coal, canals, quarries and railways. Unlike the frilly and florid ensembles of her fellow society ladies, she sported austere head-to-toe black most days, perpetuating the stereotype.

Business success gave Anne the ability to craft her own little fiefdom at Shibden. The grounds would be improved, woodland walks created, gardens planted and the old house sensitively repaired. Any self-respecting gothic novel demanded a tower and a tunnel, which Anne duly added. The interior of the hall was replanned, the tunnel dug to divert the servants away from the private rooms. Commenced in 1838, the gothic tower housing her library and private writing-space said it all. This tower was perhaps her biggest diary entry! A true gothic folly, rugged and mysterious with its pointed windows and buttresses, it was both a beacon and her safe refuge from the outside world. The symbolism is endless: it was her heart, her retreat, her lair … and ultimately her sensuous stone sex trap.

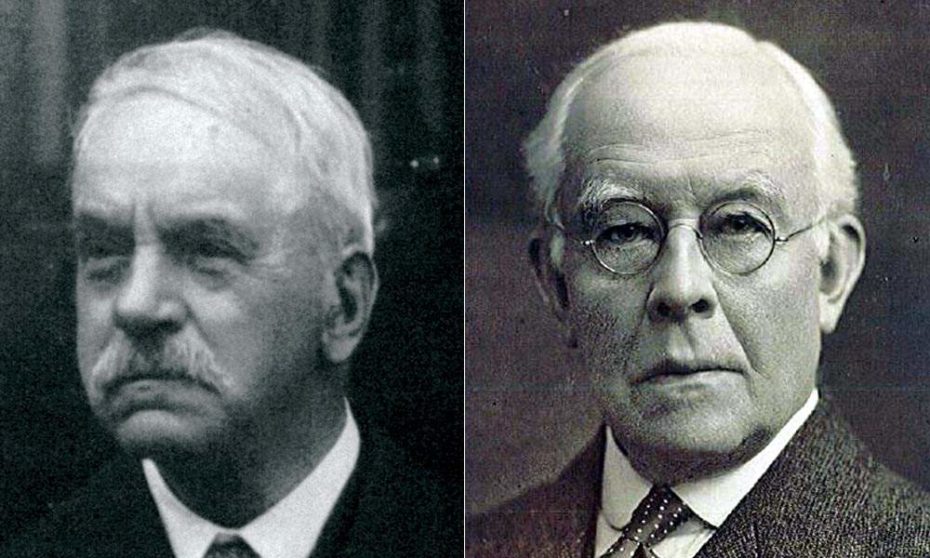

Befittingly the final act to this gothic alternative reality occurred when Anne died while travelling by carriage through the southern edges of the Russian Empire at Kutaisi, Georgia in 1840. Her ‘spouse’ Ann Walker, never inherited Shibden, but was willed a life rent. Ann lived there for a time, but was later removed by her parents to a mental illness asylum. John Lister, a family member, hid Anne’s diaries behind oak panelling in one of the bedrooms of the old hall. In 1887, John Lister and his partner Arthur Burrell, a ‘closet’ gay couple, reopened the panelling and started to work, deciphering the masses of uniquely mixed text, ciphers and symbols left by Anne Lister….

When confronted by the intimate detail, the pair thought to destroy the work, but fortunately reconsidered, and all was again concealed behind the panelling.

Shibden was acquired by Halifax Town Council in 1934. Arthur Burrell, still alive, was able to provide the key to the hidden code. The existence of the diaries was not acknowledged by the Town until the 1950s, the rich content never divulged. Not until the 1980s, in a more accepting world would they be made available to the public. In 2011 the Diaries were placed on the UNESCO Memory of the World Register.

Shibden Hall has survived almost untouched since Anne’s departure to eastern Europe and her untimely death. It is now a public museum. When the diaries were first translated, their originality was treated with skepticism. They must be fakes, it was all too graphic and lustful even for the 20th century’s taste! Only the recent verification, publication and a BBC TV series have given Anne Lister’s desire for a sexually-active lesbian life some credence, albeit the detail not yet for family viewing. Regarded as the ‘first real lesbian’, she is now a stunning example of a woman who took control of her life – from relationships to residence, from business to botany and celebrated and enjoyed her sexuality as best she could under the circumstances.