Women have undeniably had a roller-coaster ride throughout the ages. Forever pawns in a power game, the role and image of women have been in constant flux, from being portrayed as the virginal, divine, untouchable ‘Mary Mother of God’ to ‘The Whore of Babylon’. The all-male regime never quite knew whether to love or hate, adore or demonise women. Powerful women of the time were to be treated with caution and fear; historic beacons like Eleanor of Aquitaine and Joan of Arc both achieved great social standing for their achievements … and ultimately suffered their fates. As would the pious Béguines, self-sufficient women-only communities that once existed across Medieval Europe – possibly the first feminist movement – which was ultimately destroyed and everyone involved, condemned as witches.

Europe in the 13th century was more prosperous than ever, but beset with constant wars which left women destitute and countless children fatherless. The Roman Catholic Church and its vast network of parishes, cathedrals and abbeys would only do so much to assist the needy; the survival of widows and orphans required something more. From the early 13th century, a loose movement of concerned women, the Béguines (origin and meaning of the name unknown) had started to spring up in towns and villages, not as formal institutions, but as local refuges, for mutual support and outreach. These discreet communities of like-minded charitable women were determined to respond to the suffering of the disadvantaged, beaten, abandoned, and even the rescue of children from the clutches of prostitution. Béguine women were never nuns, they had no religious affiliations, they were solely motivated by a mutual desire to provide service, support and welfare to the less fortunate in society.

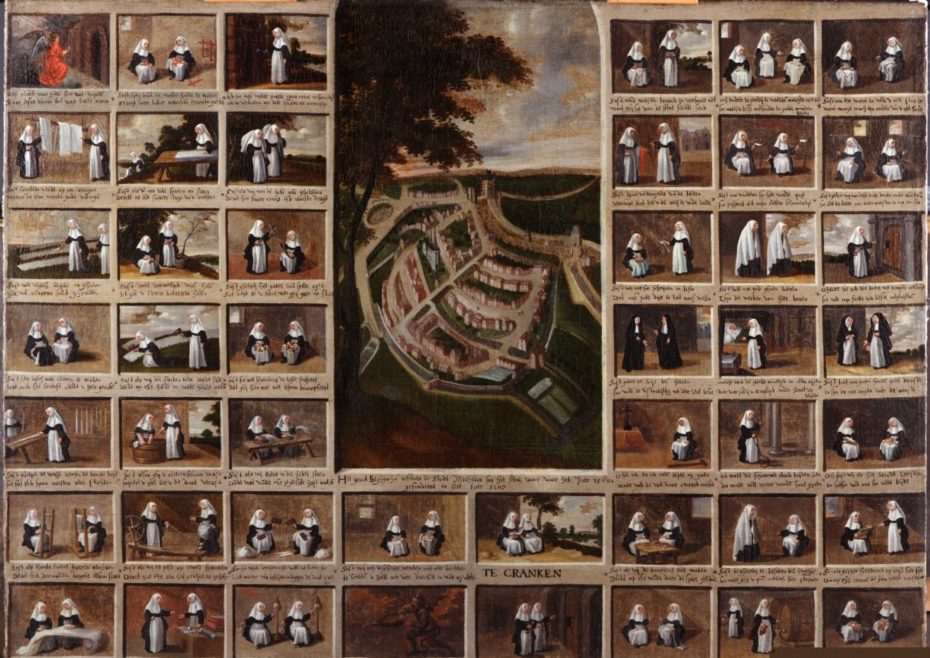

They typically lived in shared quarters known as Beguinages but had no religious ‘mother-house’, no central authority, no rules, no doctrines or dogmas – they were simply what we would call today, ‘benevolent’ or ‘public spirited’. As neither a religious order, nor a convent of any kind, the women could choose leave their Beguinage at any time, and wealthier Béguines lived alone in their own homes within the community (blasphemy for women within Medieval society) and provided support for houses that hosted numerous poorer Beguines in dormitory living. Going into the 14th century, the Béguine movement had flourished and blossomed, particularly in northern France and the Low Countries (now the Netherlands and Belgium). Most communes in the Low Countries had a Beguinage, many of the great cities had two or more.

The Roman Catholic church tolerated these women, so long as they remained pious, knew their place and didn’t compete with the functions of the religious orders. The all-powerful church would not put up with any competition, but was happy for an invisible service to mop up some of its duties while it still got the credit.

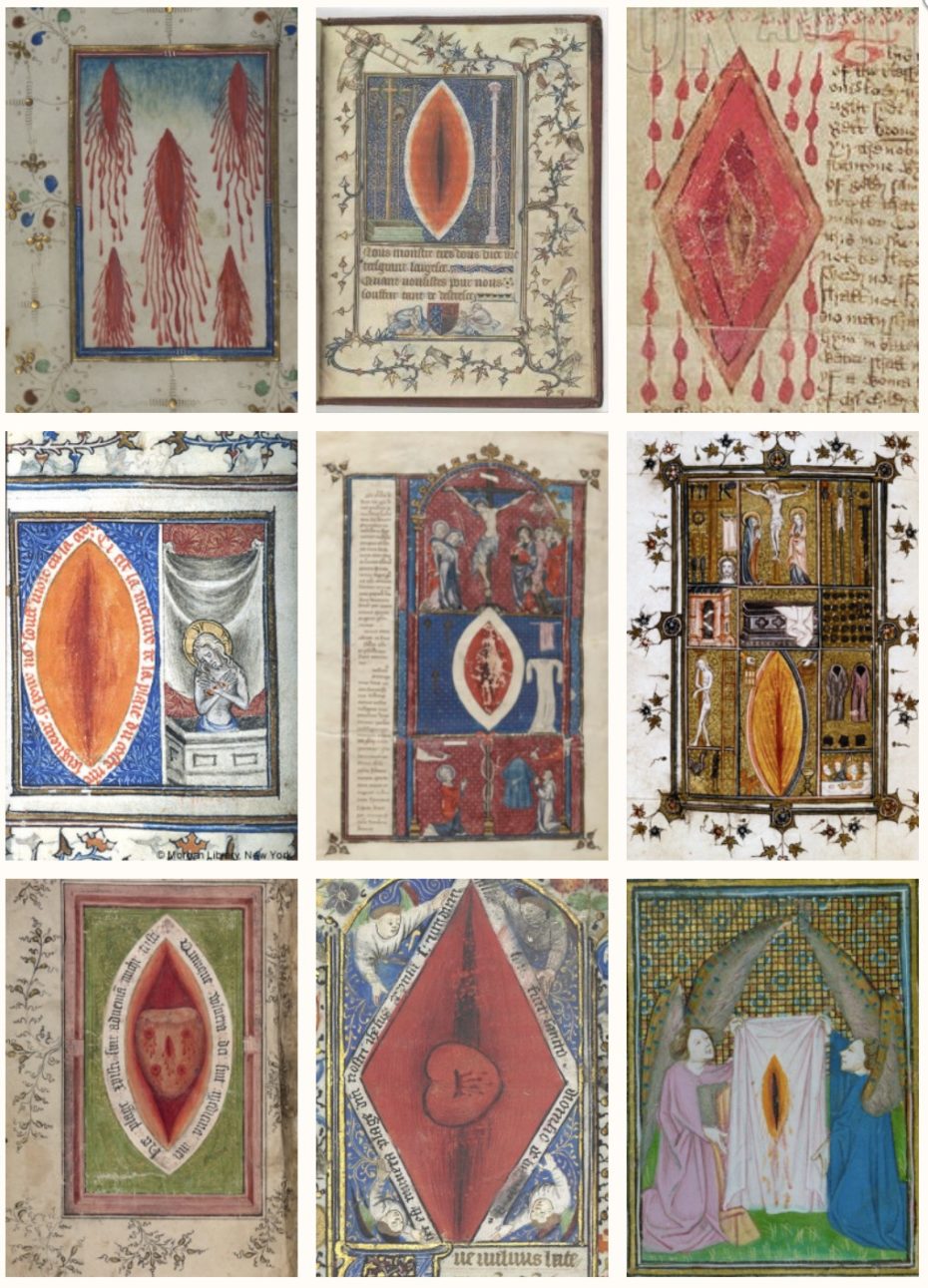

Medieval religious practice was obsessional, one’s survival was dependent upon your public profile for devotion to god. But the Béguine women could quietly and inconspicuously study and explore all aspects of their faith.

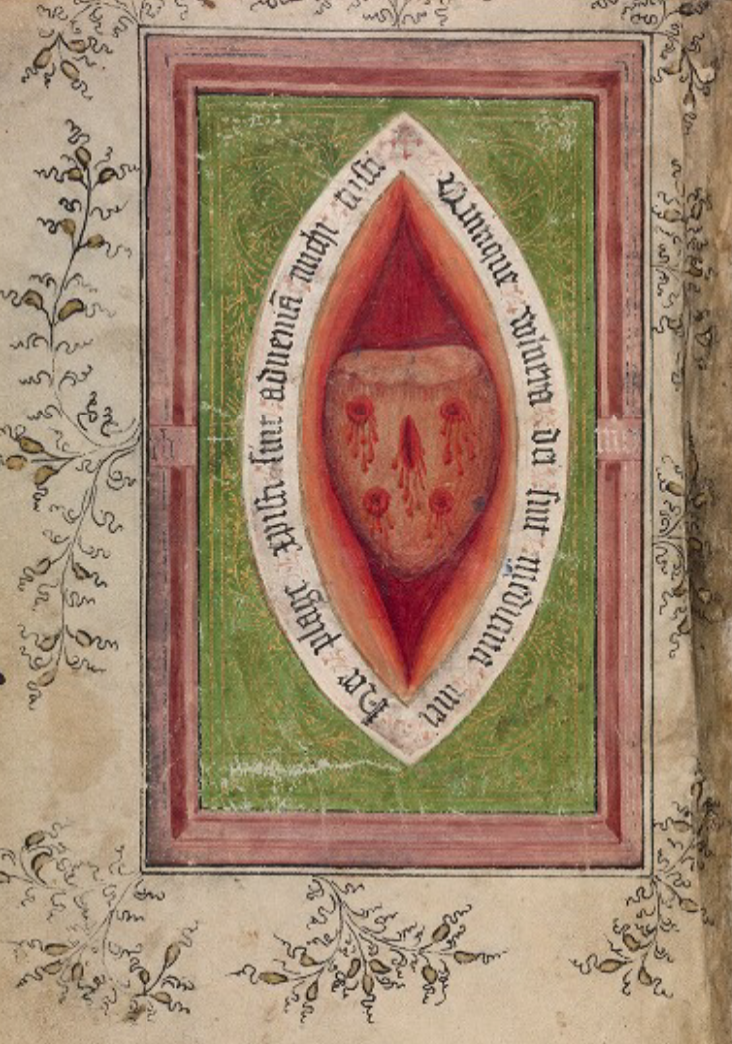

Indeed, such intimacy is thought to have nurtured an unspoken lure of the eroticism of the crucifixion of Christ for many religious women. The stabbing of Christ on the cross could, by some, be interpreted as a vaginal allegory, very much a female ‘wound’, not only provoking a bisexual identity but suggesting that there was perhaps an acceptable homosexual component to true devotion.

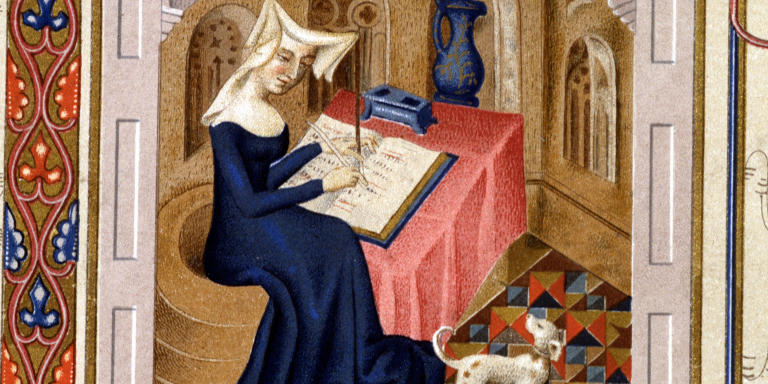

The opportunity to be able to engage in such intellectualisation of religion would be a powerful draw to the Béguine communities for women from all walks of life, rich and poor, powerful and destitute. Whilst they lived in simple common houses and dressed in humble attire, there was an intellectual, spiritual and physical bond that brought these like-minded women together to share their lives. The enduring legacy of the Béguines, particularly the educated, was the writing of intense and deeply spiritual texts on intense, ecstatic and almost erotic religious love.

The Catholic Church still jealously and violently guarded its authority and social position. The church was awash with mix-messaging: pagan Hallowe’en and Easter, May-Days and the like were switched on and off in the great religious game as it pleased the powers that be. Targets were cherry-picked, usually in the name of heresy, but inevitably there were undercurrents of politics and wealth. The early 13th century had seen the 20 year persecution and brutal extermination of the Cathars in the South of France, a religious group that criticised the wealth of church individuals and had its own interpretation of biblical texts. The early 14th century saw the legendary Friday 13th massacres and expulsions of the Knights Templar, an order that became too powerful and rich for the likings of kings and popes.

These merciful women, the Béguines, would find themselves under the same envious scrutiny from the mighty and brutal Catholic church. The church which malevolently controlled its domain would under no circumstance tolerate female priesthood or public preaching by women. This was solely men’s work! The Béguines were ‘acceptable’ under the very loose and low public profile ‘prophet’ or ‘mystics’ badge … for now. Only those Beguinages with a seemingly spotless record in chastity, piety and good deeds would be acceptable to the church, probably more out of social need than fairness or kindness. Indeed, in 1215, a Pope Honorius III had actually been as tolerant as to allow ‘pious’ women to live in ‘communal houses’ for the good and support of the communities.

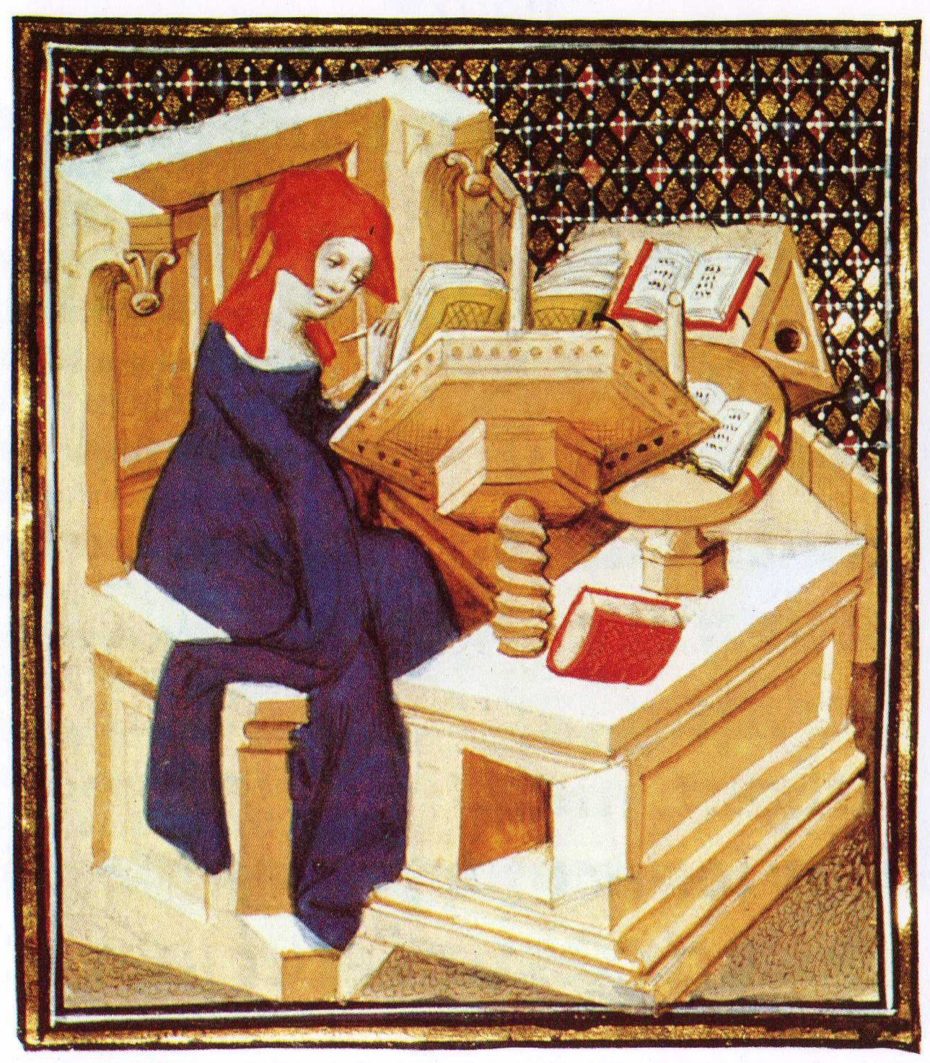

Intense religious passion drove theses intellectual lay sisters of the Beguinages to contemplate and record their desires for a divine love. While tempting the churches sensibilities, they quite clearly felt compelled to explore the pursuit of this spiritual satisfaction and esoteric ecstasy. Beatrice of Nazareth, a Dutch mystic, wrote her essay Seven Ways of Holy Love. Around the same time, Matilda of Magdeburg wrote, The Flowing Light of Divinity, an assemblage of visions, prayers and mystical observations.

Perhaps the most notable of all was Marguerite Porete (1250 – 1310), an educated and intellectual French-speaking Béguine and mystic, who penned the most enlightening of books ‘The Mirror of Simple Souls’. The book is neither a criticism of the church, nor any alternative religious text, but extols the virtues of the progression of ‘Divine Love’, where the soul travels through a sequence of seven ‘annihilations’ or metamorphoses until eventually, finding a ‘oneness’ with god. The impassioned soul would have to shed all worldly baggage and material desires before then being immersed in love and fit for heaven.

The book was a sensation. A best-seller at the time, it was copied into several different languages, including English. Unfortunately for Marguerite, the church immediately condemned the work for being full of ‘errors and heresies’ and banned circulation, with the bishop of Cambrai publicly burning copies. Marguerite had also committed the cardinal sin of writing in Old French, rather than the prescribed holy script of Latin.

Gentle Marguerite was arrested, held in prison for over a year and put on trial. The church now demanded she recant and withdraw her ‘heretical’ book, but Marguerite bravely and stoically refused. The church machinery inevitably found her guilty of heresy and she was cruelly burned at the stake in Paris on 1st June 1310. Conversely, her work never died, and the book continued to be circulated after her death, albeit under an anonymous authorship and was reprinted twice in the 20th century.

Marguerite Porete had firmly stood on the toes of the church. The Béguines and their mystic activities were now staunchly on the church’s radar and under the envious gaze of a male-dominated society. Promoting a good Christian lifestyle was fine, but usurping the holy word of the church with entertaining books, not so. The Catholic Council of Vienne in 1311 (which the followed the year after Marguerite’s burning) recorded in one of its decrees of the Béguines: they ‘dispute and preach about the highest Trinity and the divine essence and introduce opinions contrary to the Catholic faith concerning the articles of the faith and the sacraments of the church.’

The Council of Vienne was a watershed moment for the Béguines, and the fear of persecution started to erode their numbers. Many of the Béguine communities were absorbed by existing monastic and convent orders. Some, however, continued. The 15th century would see the church – again – in a brutal self-promoting frenzy, become obsessed with the fear and spread of ‘witchcraft’, which culminated with the publication of Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of the Witches) in 1486, a witch-phobic book for both church propaganda and zealot hunters. The 16th century’s Protestant Reformation continued to fan the flames of fear of witchcraft, and the Béguines were easy targets. The Counter Reformation provided a slight respite, where they were accepted into the surviving pockets of Catholicism in the Low Countries.

As societies modernised in the 18th and 19th centuries, state hospitals and welfare systems assumed the role of the charitable Béguines and the need for this gentle and helping womens-clan passed with only a handful of Beguinages surviving into the 20th century.

Outwardly, the Béguines had fulfilled a desperate need in Medieval societies to provide support and shelter for the orphaned and abandoned. They were required to keep their heads well below the parapet, their contribution was rarely seen and never heard and kept far from the history books. Below the parapets, in the seclusion of their private chambers, was their unseen private esoteric world, intimate and divine, sensual and safe from the threatening authority of the church. The last traditional Béguine was a Marcella Pattyn, who died in Kortrijk, Belgium on April 14th 2013 aged 92 and with her passing, it was the end of an era of a very private female independence movement.