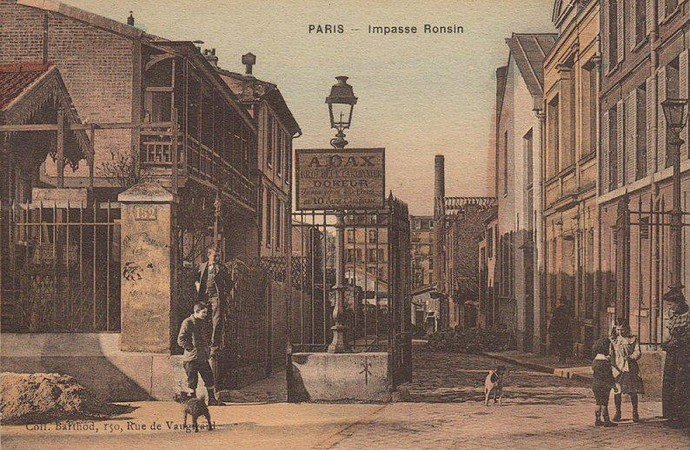

Avenue des Champs-Élysées, Rue de Rivoli, Avenue Montaigne, each year millions of tourists follow the tired and testing formula of ‘been there, done that, bought the Eiffel Tower keyring’, and often leave the city with an unfortunate case of ‘Paris Syndrome’. As you may already know, we are not tourists here. We choose the path less trodden, in hope of a trip down the rabbit hole into unknown and unusual Paris. Often it’s the least suspecting places that are hiding the biggest secrets. Take our hand for a stroll back in time down a skinny, squalid alleyway in the 15th district, which although doesn’t sound it, was once Paris’ hottest postcode.

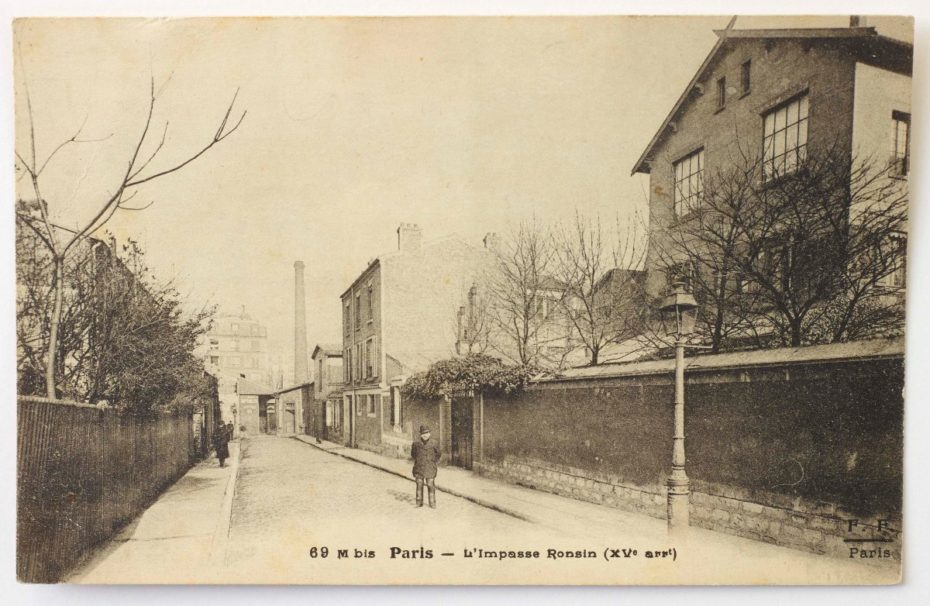

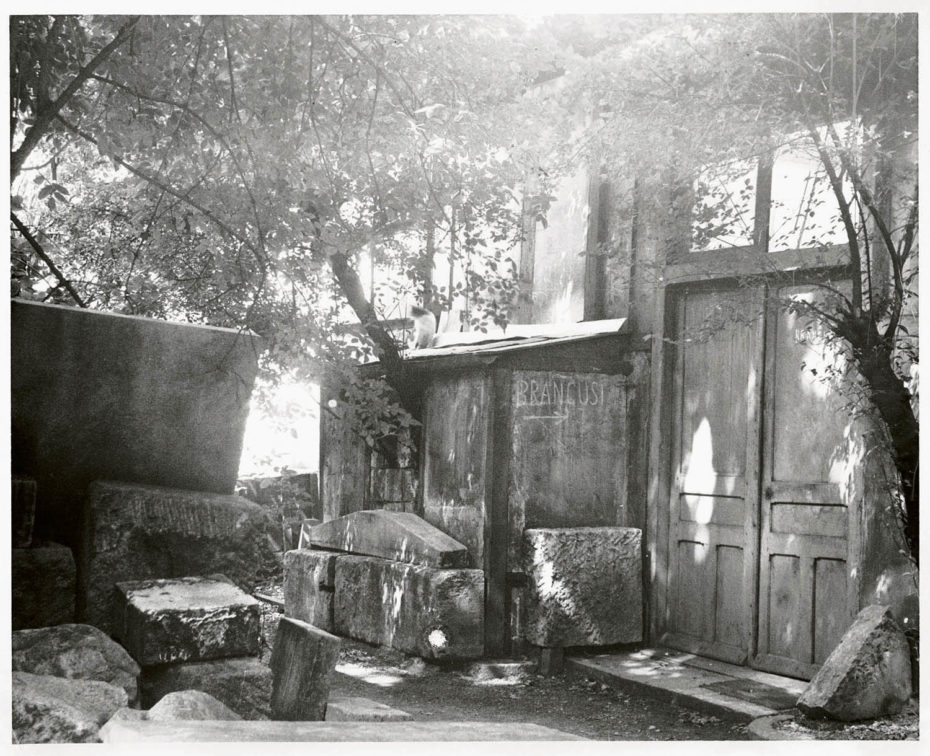

Art can flourish in the most unappealing of places, after all, history shows a certain amount of squalor can spark creativity, or least provide a penniless artist with a grungy little studio for a reasonable rent. In 1916, a curious cul-de-sac south of the Seine, nicknamed ‘the filthiest place in Paris’, was once the beating heart of the modern art world; a nucleus of chaos, poverty, fame, and obscurity.

Small but mighty, Impasse Ronsin did more than simply home a whole host of world-famous artists and their alliances for almost 50 years. It was here, amongst the rats and stray cats, that priceless art was created, and ceremoniously destroyed. Artist colonies and cooperatives have existed for centuries, but this slither of a street in Montparnasse changed the course of modern art forever. Limits were pushed like never before, and no, we’re not just talking about their overflowing laundry piles.

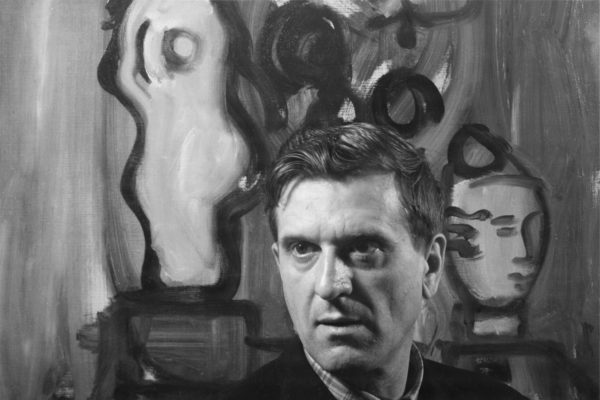

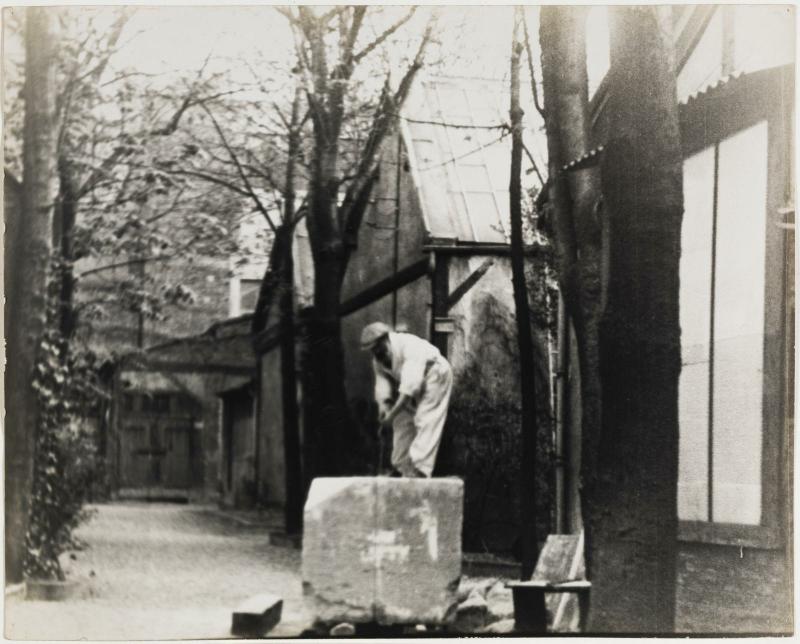

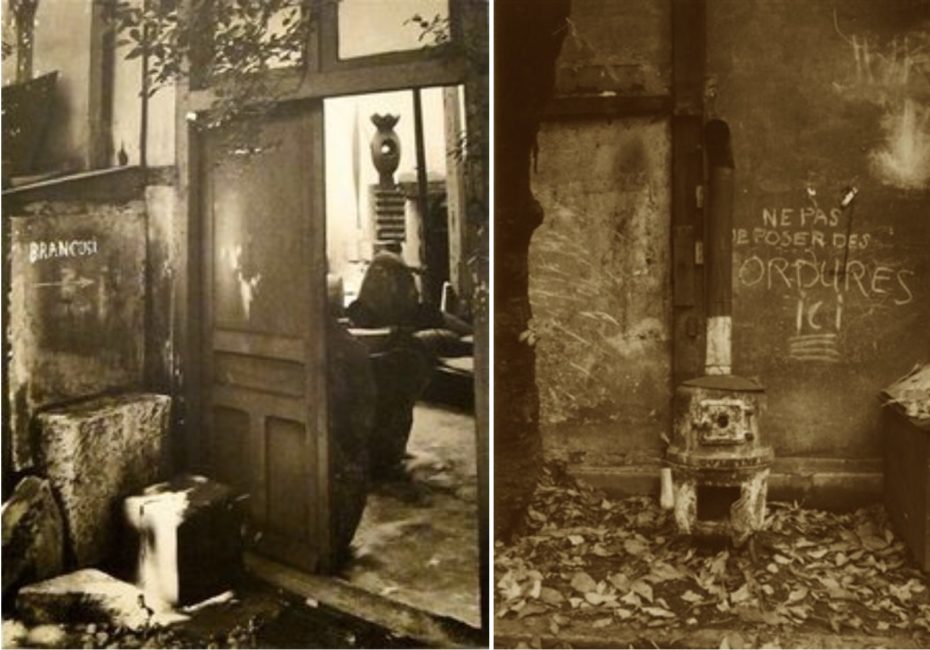

One of the most well-known residents, who was on his way to becoming the wealthiest artist on the scene, was Constantin Brâncuși. In 1916, the young Romanian sheepherder with a passion for woodwork moved into what was a flourishing but still under the radar artistic collective. He would later go on to pioneer the Modernist movement and become one of the most influential sculptors of the 20th century.

A serious artist you may think, but often omitted from his biography is the fact that as he was cutting his teeth, and wood, down this tiny French alleyway, Brâncuși’s place was the undisputed party house on the block.

As his sculptures made him some money and his reputation grew, so did his workshop and living space. Stretching over five lots, Brâncuși’s place boasted hot running water, handmade wooden furniture (obviously), and a fridge solely for champagne, a sign of his success and the billionaire businessmen friends who started to visit from across the pond.

Despite occasional drop ins from more affluent folk, Brâncuși didn’t forget his roots. Leaning into the cul-de-sac’s convivial cooperative spirit, he would often cook traditional Romanian meals for his neighbours, providing them with a moment of comfort and a brief break from their less luxurious squats. There was always plenty of wine, women and cigarettes at his place too, all of which were kindly shared around. Brâncuși lived, loved, worked, cooked and created on the Impasse until his death in 1957.

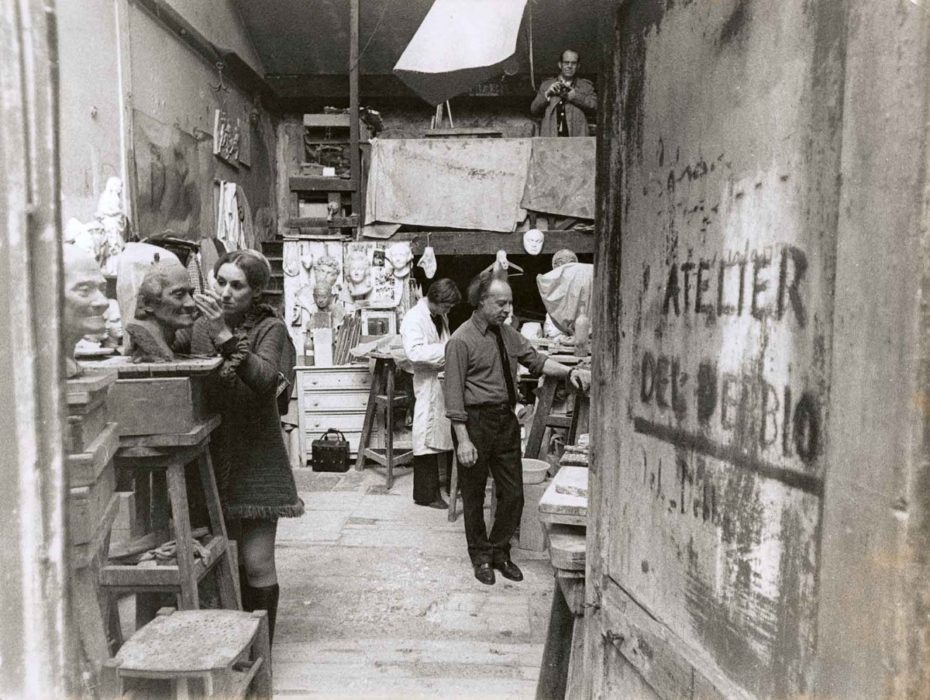

Some 220 artists were Brâncuși’s neighbours at one point or another. Initially obscure and unknown, many would leave as mainstay names in the art world and beyond. Come the 1930s, a bunch of avant-garde amateurs moved in whose dream-like doodles and creative collages of the uncanny and unconventional later became masterpieces of the Surrealist art movement. Marcel Duchamp honed his skills here, and probably his chess playing too, all while living in close proximity to so many other brilliant minds of his generation, such as Dada’s New York darling, Man Ray.

Everyone wanted a taste of true Parisian bohemia, no matter how grubby and gritty it was. That was its charm, after all. Peggy Guggenheim dropped by, so did Ezra Pound, Pablo Picasso and even Vice President Rockefeller, all clambering over crumbling walls and dodging the roaming goose who lived amongst the renters.

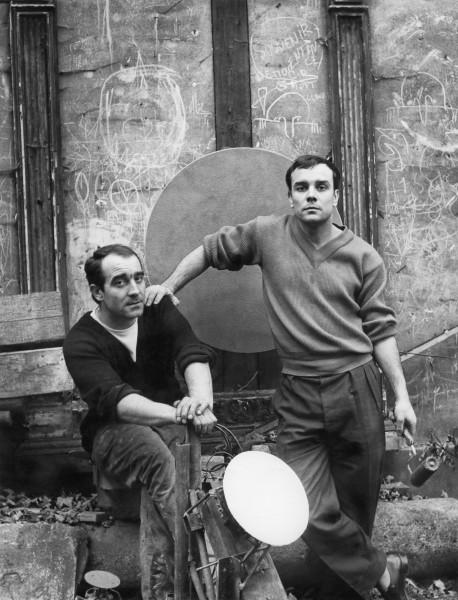

It wasn’t all work and no play on Impasse Ronsin, and that was perhaps the reason why such a tightly knit and prolific artistic community grew. When Yves Klein wasn’t pinpointing the perfect shade of blue, he made a killer soup for swiss sculptor Jean Tinguely and his then wife Eva Aeppli, whose apartment was likened to a rubbish dump. Comfortable in his role of the feeder, Klein even hosted his wedding reception at no. 11 on the alleyway in 1962. His wife, Rotraut Klein-Moquay, described the relative poverty of the Impasse as ‘paradise; full of fantasy, inspired by everything and just living for the art’.

Aside from artistic collaboration, this shape shifting group of now world-famous intellectuals were first and foremost neighbours, bonding over broken appliances and communal meals, like in any friendly flat share. Because of this, great things started to happen down this dead end street. There’s beauty, and art, in the everyday, even if that’s delivering the mail and doing the dishes, especially priceless pots and pans made by Brâncuși himself.

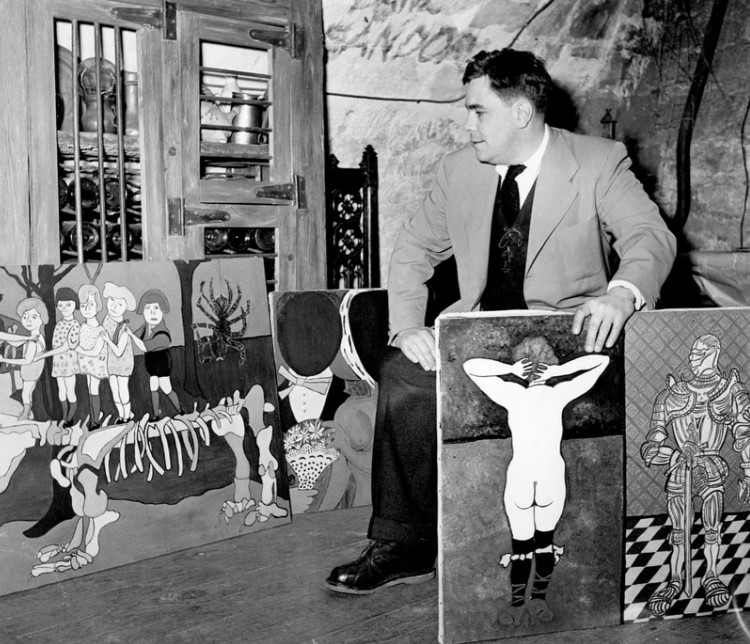

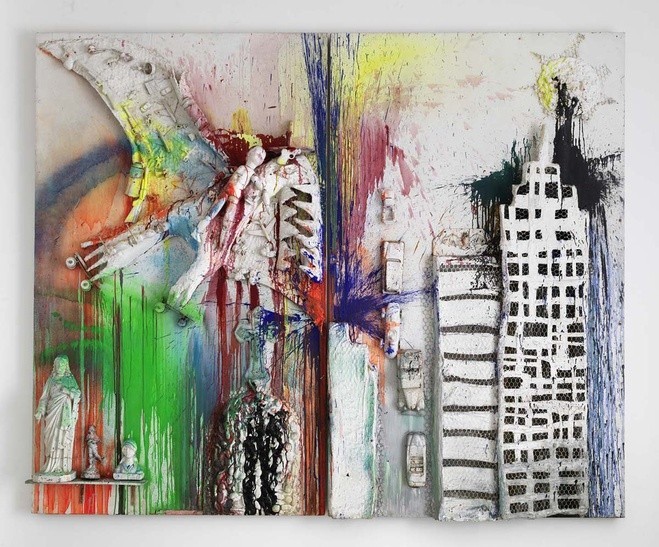

As idyllic the humble suppers may sound, Impasse Ronsin was far from a place of serenity and security, that includes playing it safe artistically too. Forget sirens, it was gunshots that echoed throughout the arrondissement. Former Vogue cover girl and outsider artist Niki de Saint Phalle relaunched her career with a bang by swapping the paintbrush for a rifle. The pressure cooker of experimental art she witnessed down this trash-strewn side street triggered her ‘first great artistic crisis’. In a burst of violent creativity, it was here in 1961, where she staged her radical ‘Shooting Paintings’. Quite the spectacle, members of the audience were also invited to take aim at the bags of paint pinned to canvases, including American artists Jasper Johns and Robert Rauscheberg.

Impasse Ronsin was pivotal to Saint Phalle in more ways than one. She later reconnected with fellow Ronsin alumni Jean Tinguely to collaborate on art projects such as the iconic Stravinsky fountain now located next to the Centre Pompidou. The pair ended up getting married in 1971, proving that relationships formed during the glory days, be them romantic and artistic, stretched well beyond the tenancy agreements.

Even before the artistic violence of Niki de Saint Phalle, it turns out, armed and dangerous eccentrics were nothing new down this dingy dead end. Radicalism and notoriety ran deep below the cobblestones. In 1897, almost a decade before the artists moved in, Impasse Ronsin was the infamous address of femme fatale and mischievous mistress to many prominent men, Madame Marguerite Steinheil.

Unknown to many nowadays, her salon at no.8 became an underbelly hotspot of Parisian high society, frequented by highflying composers, diplomats and poets, including Emile Zola, making Madame Steinheil the talk of the town in the late 19th century and earning her the nickname ‘The Red Woman of Paris’.

In 1899, her salon on the Impasse was the site of national scandal and outrage when French President at the time, Félix Faure, mysteriously died in her company, allegedy midfellatio. To add fuel to the fire and keep the rumour mill churning, 9 years later, 8 Impasse Ronsin was a crime scene once again, with Ms Steinheil strongly implicated in the murder of her husband and mother. Rather amazingly, she was acquitted and went on to marry an aristocrat and live a peaceful life on the English coast. This rotten alleyway has certainly seen it all, and it sure says a lot when a lady like this gets overshadowed by a particularly special sculptor who moved in a few years later.

Sadly the plug was pulled on the party in the 1950s when the neighbours complained about the noise. The attention Impasse Ronsin gained over the years led to more intense investigation and it was eventually declared unfit for habitation by the authorities resulting in the land being seized by a nearby hospital. Its last big blow out was in 1963 when young Argentinian artist and pioneer of installation art, Marta Minujín, decided to theatrically, and rather symbolically, destroy all her work, marking the end of an era. She invited other artists to bring themselves, their work and some matches to an empty lot on the Impasse at 6pm sharp on June 6. Talk about kissing those rental deposits goodbye and vacating the street with a ceremonious crash bang wallop.

Sadly the wildly bohemian world of Impasse Ronsin is now lost, its charred remains destroyed forever and blocked off with private property signs. Even googlemaps doesn’t indicate the site’s importance or permit a virtual walk down the historic side street.

As is often the case with sacred slithers of bohemia around the world, poetic privation gets privatised and sold off the highest bidder. Too bad most of the artists living down Impasse Ronsin couldn’t cash their cheques in time. It’s funny to think what modern art would be like today if this old dead end street never was. The inside, and outside, of the Centre Pompidou across the Seine sure would look different, that’s to say if it would exist at all.

While you’re over on the Right Bank, across the piazza from the Pompidou, you’ll find one of the city’s secret museums, Atelier Brâncuși, an exact reconstruction of the sculptor’s studio as it was in Montparnasse, commanded to be saved by Brâncuși himself in his will. There may not been any roaming geese, stray cats or piled high trash cans surrounding his transported workshop these days, but perhaps ‘the filthiest place in Paris’ is better remembered with rose tinted glasses than lived in actual reality. Or at least that’s what those of us who weren’t there can tell ourselves.