On the morning of January 30, 1889, three friends of Rudolf, the Crown Prince of Austria, broke down On the morning of January 30, 1889, three friends of Rudolf, the Crown Prince of Austria, broke down the bedroom door at his hunting lodge to find him dead, sitting by the naked corpse of his teenage mistress. For more than a hundred years, people have speculated wildly at the events surrounding this double suicide – or murder suicide –– depending on whom you ask. One thing seems to be consistent, though: through the butterfly effect, these untimely deaths not only symbolized the destabilization of European monarchies, but they had global repercussions. This tragic romance directly triggered the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which led to the subsequent start of the First World War, ending in a peace agreement that would ignite the embers for a Second World War just two decades later, and finally, set in motion a 45-year long Cold War between East and West that arguably continues to this day. Our world would be completely different had they lived.

The progression of global events is indisputable, but the facts of that night are messy. To understand the story, we have to understand the characters, and perhaps even more importantly, we have to understand the setting. A few key things to know:

Franz Joseph was the reigning Emperor of Austria-Hungary in 1889, an empire of myriad ethnic and national groups, many of whom wanted their own nation-states. Franz Joseph would not give them independence, instead allying the empire with Germany. Before his death, the Crown Prince Rudolph, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, sympathized with those wanting their independence, even had liberal political views in opposition to the notoriously conservative Emperor, his father. In fact, he didn’t want to get too close to Germany, and he’s quoted as saying in Greg King and Penny Wilson’s Twilight of Empire, “Germany needs this alliance more than we do.”

His empathy for the little guy wasn’t the only thing that was sexy about Rudolph. His friends knew him as a sensitive soul, as did many mistresses. The Crown Prince Rudolph had been married for eight years by the time of his death, to Princess Stephanie, who was … a royal obligation. She was, according to the New York Times, “plain, oddly colorless. She had little education, a hot temper and a stubborn will. At the time of the marriage she was only 15, a gawky schoolgirl.” They had one daughter together, Elisabeth, known as Erzi.

Only one daughter — not the ideal for a royal couple that depends on a male heir. Why just the one? Due to his sexual affairs outside the marriage, Rudolph infected his wife with syphilis according to one Los Angeles Times article, which rendered her unable to have more children.

Maria Vetsera, the 17-year-old baroness who was the other body at the scene of the mysterious deaths, was only the most recent in a line of mistresses. And according to a 1964 New York Times article, “she had fine eyes, a pert nose, a generous mouth and a determined little chin. She was no ravishing beauty, but she was pretty and undeniably seductive. She had flowered early and looked older than her years. Her mother was the daughter of a rich Armenian banker from Constantinople, her father belonged to the lesser Austrian nobility… She was warm‐hearted, empty‐headed, a creature of impulse.”

Apparently, Maria Vetsera was not even the first woman to whom he proposed a joint suicide. Rumor states, and Lucy Coatman confirms, that he had asked Mizzi Kaspar (by turns a prominent courtesan, police spy, pretty dancer, actress, and agent of the German Government, again, depending on whom you ask) to be his in death first. It was after she refused that Rudolph asked Maria.

Rudolf even wrote a goodbye letter to Mizzi right before his death, according to Karoly Lonyay’s writing, “Rudolph, the Tragedy of Mayerling.”

But, Maria Vetsera did love Rudolph, and by most accounts, she agreed to this suicide pact. In retrospect, though, examining their age difference and power dynamic, it’s unclear if she believed she really had a choice, which is one reason why the Mayerling Incident, as it is known in history, is just as often referred to as a murder-suicide.

So that you can draw your own conclusions, here are the facts of the evening.

Pretty much everyone at the Imperial Court knew that Rudolph and Mary were having an affair, even his parents (the Emperor and Empress) and his wife, Stephanie — this, according to William Tuohy’s article at the LA Times.

A few days before the Incident, Rudolph attended the birthday celebrations for German Kaiser Wilhelm II at the German Embassy in Vienna. There, he was cordial to everyone but his wife Stephanie, who loudly ordered him to fetch her ermine cloak. He told her, “Go to blazes with your silly cloak!” and left the party early.

He spent the night with Mizzi Kaspar. The next day he drove to Mayerling, where he was joined by Maria Vetsera. He arranged for a hunting party at Mayerling, the lodge he had purchased three years earlier. His parties were unconventional, having casual dress code, minimal decorations, and informal conversation. According to Lucy Coatman at History Today, his valet Loschek and friend Joseph Graf Hoyos went to wake him for the hunt on January 30, but got no response. They tried to open the door, but it would not give. Fearing the worst, the two men discussed what to do with Prince Philipp, newly arrived. They decided, and smashed in one of the door’s panels so that they could open the door from inside. Loschek (the valet) alone entered and reported back.

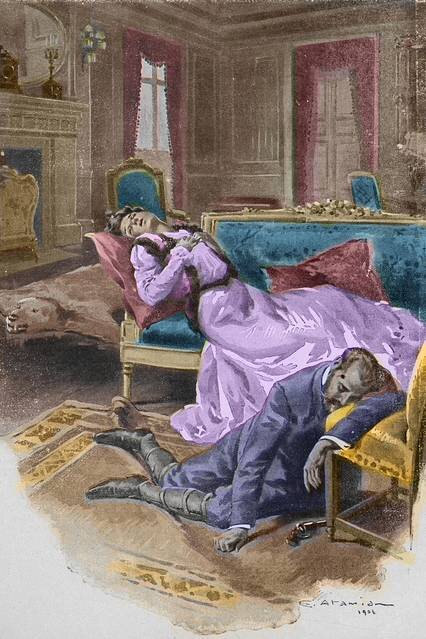

What he found was both Rudolph and Maria dead, Maria stretched out on the bed, and Rudolph leaning over its edge, a pool of blood in front of him. Loschek assumed Rudolph had taken strychnine from the glass by the table, but he must not have seen clearly due to the dim lighting: “half of Rudolph’s skull had been blown off by a bullet fired at close range.

“The mistaken impression that poison was involved, and even that the baroness had poisoned the Crown Prince and then killed herself, would persist for some time.”

Immediately after, though, the Imperial family tried to hush-up the scandal. The Minister President of Cisleithania, issued a statement at noon documented in Edwin Emerson’s A History of the Nineteenth Century on behalf of the Emperor that Rudolf had died “due to a rupture of an aneurysm of the heart.” And, the official gazette of Vienna reported the same.

The family attempted to state that Maria had died on her way to Venice, and her uncles propped up her body with a broomstick to cover-up the double suicide as they left the lodge. Vetsera was quickly buried, and the imperial court refused to let Vetsera’s mother see her daughter’s grave for over two months after the burial. But Lucy Coating states in her article “Love is Dead” that Maria would find little rest even in death. Her remains were exhumed numerous times over the next century, and as recently as 1991, her bones were stolen by an infamous “Crypt Thief” before being returned two years later.

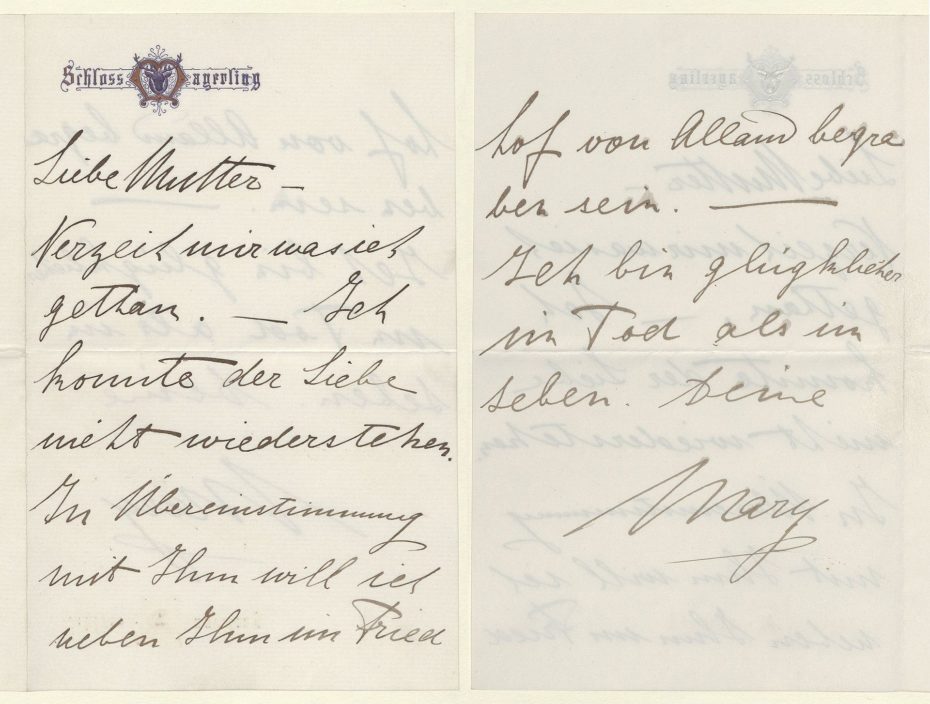

Several suicide letters were discovered alongside the bodies. They could have easily been written by a skilled forger, since According to the NYT revisited 1964 New York Times investigation, “It was a time when the forgery of letters had been elevated into a fine art, especially in the secret chanceries of state.”

Many men in high positions wanted to get rid of Rudolph for his liberal ideas, so it’s certainly not beyond reasonable doubt that they were illegitimate.

In 2015, however, a bank archive in Vienna discovered Maria Vetsera’s suicide notes in a safety deposit box locked in 1926. The letters—written in Mayerling shortly before the deaths—state clearly and unambiguously that Vetsera was preparing to commit suicide alongside Rudolf:

Dear Mother

Please forgive me for what I’ve done

I could not resist love

In accordance with Him, I want to be buried next to Him in the Cemetery of Alland

I am happier in death than life.

Back in real time, though, “foreign correspondents” learned quickly that “Rudolph’s mistress was implicated in his death,” and the “first official version” of cardiac arrest was dropped. “It was announced that the Crown Prince had first shot the baroness in a suicide pact, sat by her body for several hours, and then shot himself.”

Because of a recent fight with the Emperor his father, over ending the extra-marital liaison, the police closed investigations quickly, stating that the deaths happened “while the balance of the Archduke’s mind was disturbed.”

Unlike Maria Vetseva, whose body was buried with the other suicides, because of Franz Joseph’s political pull, Lucy Coatman says in her article, “Mater Dolorosa: Elisabeth in the Aftermath of Mayerling” the Church granted a blessing for Rudolph’s burial in the Imperial Crypt, which would not normally have happened in the case of a person who committed murder and suicide. Because of the Vatican’s special dispensation, his body now rests with the other Habsburgs in Vienna’s Church of the Capuchins.

Crown Prince Rudolph was the only son of Franz Joseph, which interrupted the line of Habsburg succession. The Emperor’s brother, Karl Ludwig, was heir-presumptive, but he soon renounced his right in favor of his eldest son, Franz Ferdinand. This destabilisation of the Habsburg dynastic succession endangered the growing reconciliation between the Austrian and Hungarian factions.

Franz Ferdinand of Austria and Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg

After succeeding in 1914, the conservative and monarchical Emperor Franz Ferdinand and his wife were gunned down in Sarajevo by a Slav nationalist. The assassination precipitated the July Crisis which led to Austria-Hungary declaring war on Serbia, marking the start of the First World War.

According to many theorists, had those fateful lovers never entered into their suicide pact, and the Prince had lived to rule as Emperor instead of Franz, Rudolph’s liberal philosophies might very well have saved Europe and the world from war.

Fate rules the affairs of mankind with no recognizable order.

Seneca