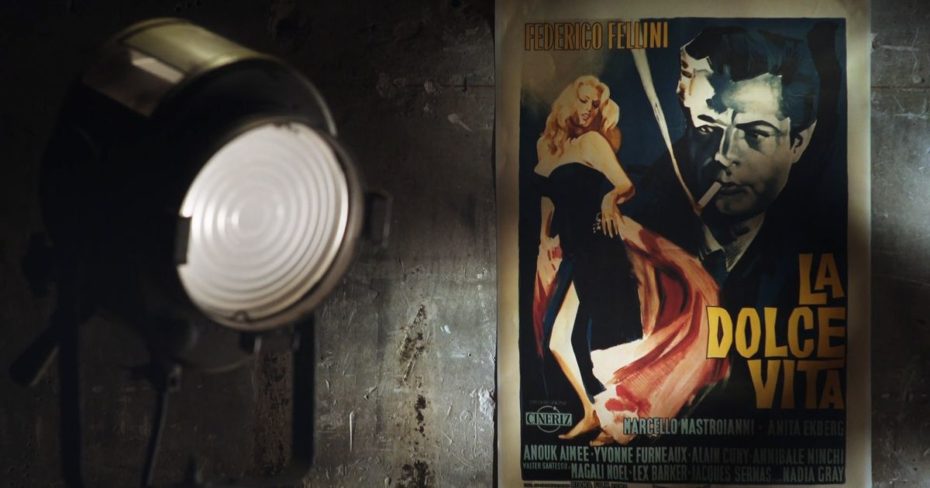

Italian cinema is synonymous with hauntingly special silver screen moments, the stuff that flashbulb memories are made of. Who could possibly forget the larger than life screen goddess Anita Ekberg – all platinum locks, bare shoulders and curvaceous black dress in Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita? Or the doe-eyed flamboyant gamine Audrey Hepburn on her bicycle in William Wyler’s A Roman Holiday? Over 3000 movies and counting have been made at the studios, and so prolific was its international output and reputation that in the 1950s, Cinecittà World Studios were referred to as ‘Hollywood on the Tiber’ by one Time magazine reporter. In fact, there were so many stars in and out of the studio gates in post-war Rome that we can thank Cinecittà for the creation of the celebrity-chasing culture we know today as the paparazzi.

At a whopping 44 000 square meters, Cinecittà World Studios are not by any stretch of the imagination humble starting blocks. Neither is there anything remotely modest or mediocre about their eventful past that spans eight action-packed decades with some seriously toothsome historic ingredients including a treacherous World War, a fascist dictator, some shell-shocked refugees, merciless bomb attacks, bankruptcy and a few devastating fires in the cocktail. Add a bevy of scorching hot Hollywood stars, a pinch of paparazzi and stir it into the delectable Eternal City of Rome and you have yourself a recipe that was always destined to allure, entice and intrigue.

The golden era of film production in Italy was off to a questionable start with fascist dictator – and avid movie lover – Il Duce, aka Benito Mussolini as its architect. Perhaps not the fairy tale beginning to the story of legendary il cinema fans would’ve preferred, but that was the way things panned out for Italian cinema – and indirectly Hollywood – in the pre-WW2 years. So obsessed was Mussolini with the silver screen and its shining stars that he allegedly sent over 100 love letters and various marriage proposals to American screen goddess Anita Page. He was also instrumental in the establishment of the Venice Film Festival, the oldest film festival in the world.

Il Duce understood only too well the exponential and emotive power of moving images as a propagandist tool, and the immeasurable impact films can have on national morale and culture. He actioned his own propaganda factory under the national slogan, ‘Il cinema è l’arma più forte’ (‘cinema is the most powerful weapon’) by seizing the opportunity to the largest film studio in Europe. This new powerhouse of international cinema, Cinecittà World Studios, was opened in 1939 on the south eastern edge of the city.

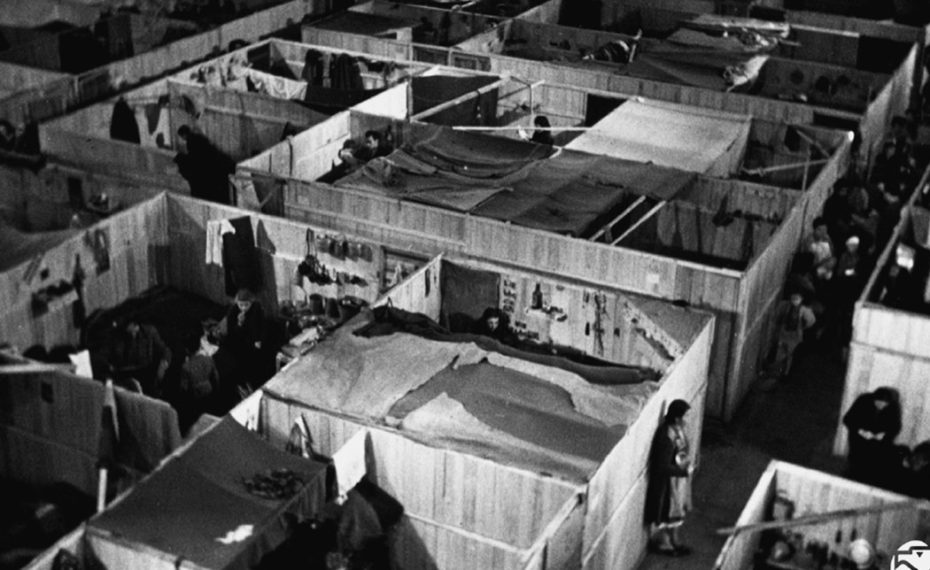

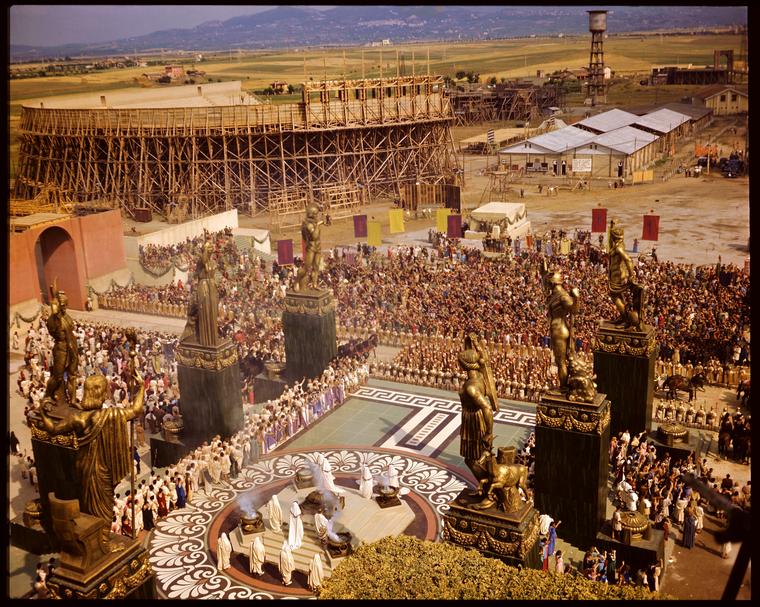

Initially, it dabbled with a few relatively underwhelming nationalistic films – Scipio Africanus (despite a cast of 7,000 people and live elephants at the scene at the Battle of Zama) in 1937 and The Iron Crown (1941), but this tenure was short-lived as WW2 erupted in 1939 and the studios were partly destroyed by the Allied bombing of 1943/4. Between 1945 and 1947 the studios became home to 3,000 displaced Italian and international refugees, camping on the massive sound stages. Some even ending up doubling as extras as the studio attempted to resume production.

In the same period, the studios were yet again rebuilt for post-production purposes. The world forgave Italy and with Mussolini now gone, new filmmakers flocked to Rome’s Cinecittà World Studios, beguiled by the cheap labour costs and the unbeatable beauty of Rome as a backdrop, to make films about real people and everyday life in the Eternal City. Italian ‘Neo-realistic’ films like Rosselini’s Rome, Open City (1945) and Bicycle Thieves (1948) were produced, their success paving the way for the big gun productions like Quo Vadis (1949).

With ambitious productions like Beat the Devil and Roman Holiday in 1953, The Barefoot Contessa (1954) the following year, the biblical epic Ben-Hur in 1959, popular and successful films kept being churned out, culminating in what’s universally revered as one of the most elegant films of all time, Fellini’s La Dolce Vita in 1960. International productions of note also saw the light during this time at the studios: Francis of Assisi (1961), Cleopatra (1963), The Agony and the Ecstacy (1965), La Traviata(1967), Romeo and Juliet (1968) and Fellini’s Casanova (1976) amongst others.

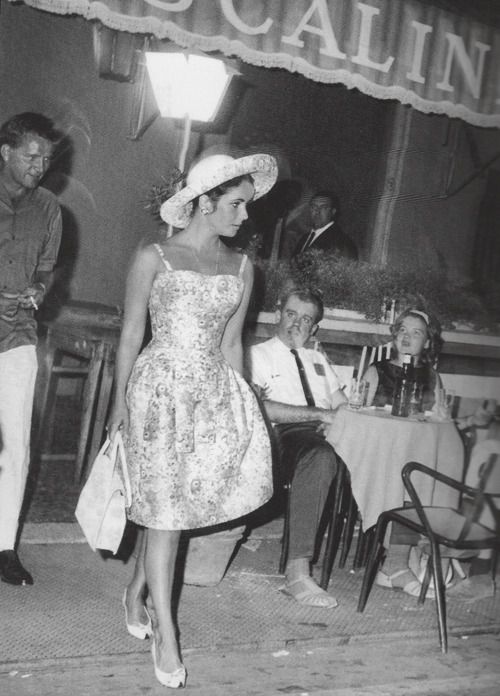

The so-called ‘sword and sandal’ epics like Ben-Hur and Cleopatra were particularly commercially successful and provided a brilliant return on investment for movie bosses. The Italian government was worried about the success of Hollywood-produced films and imposed laws to protect its own home film industry, making it difficult for money made in Italy to leave its shores. Hollywood had to rethink its strategy – and decided to use the blocked funds as budget and hence reinvest in more movies … in Italy. A phenomenally lucrative and legendary period in film history was born, luring the star-studded likes of Brigitte Bardot, Clint Eastwood, Ava Gardner, Kirk Douglas and Audrey Hepburn to Rome and to Cinecittà, exploiting Rome as a location, with its good all-year-round climate and unrivalled beauty.

And of course, no story about the film industry in Rome would be complete without mentioning Liz (Taylor) and Dick (Burton), as the tabloids referred to them, embarking on the most tempestuous affair of the century. On the 200 yard stretch of the frenetic Via Veneto, superstar players; moneyed financiers and playboys, gorgeous actors, stunning models and fashion designers to the stars; glammed up hotel foyers, danced the night away in the elite clubs, strutted their lithe bodies in bars and on sidewalks, and graced restaurants and wild parties alike. In the 1950s and 1960s, there was indeed no place on the planet remotely comparable to Rome. It was “Hollywood on the Tiber”, declared the press, and no painted backdrop in tinseltown USA could replicate the buzz, the exhilaration and the authentic allure of Rome. It was indeed La Dolce Vita.

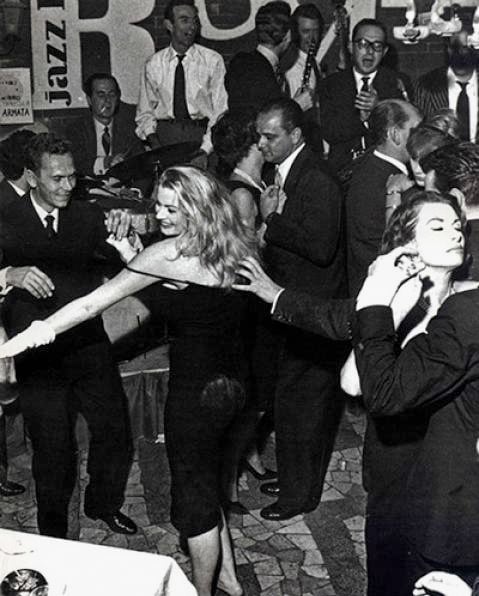

But amongst all the glamorous cavorting, the now infamous paparazzi was born. It wasn’t all of society who managed to find a place in the lucrative mainstream movie business; many struggled to find employment in this war-ravaged country. In desperation, some started to snap tourists for cash, but soon discovered that there was far more mileage in photographing the rich and the famous regularly spotted around town, especially if caught in somewhat compromising positions. One such opportunist photographer was Tazio Sechhiaroli, also known as the Fox of Via Veneto. He found his way into a restaurant one November night in 1958 where actress Anita Eckberg was frolicking at a private party. As she kicked off her shoes and started dancing barefoot, an uninvited guest – a Turkish dancer – began to strip alongside her.

The crowd went wild. Tazio snapped himself a million dollar snapshot and the tabloids were soon firmly banking on the private lives of movie stars. Photographers started sneaking into parties, hiding out and stalking celebrities – on foot and on their Vespas, they even went as far as to provoke a reaction if they couldn’t naturally find unseemly behavior. At the height of all this star snapping and melodrama on the streets of Rome, ingenious director Federico Fellini was in town and approached the notorious Tazio Sechhiaroli, asking him to share his hot gossip stories. Out of this ‘collaboration’ came one of the most epic films and memorable characters of all time – La Dolce Vita. A fellow named “Papparazzo” is the sidekick to the main character, based on none other than Tazo, who consulted on the movie. The name stuck.

Italy boomed in the post-war years with a national desire to rebuild the nation. A new consumerism was fuelled by new and stylish, well-designed products; Bialetti coffee pots, Vespa scooters and sexy racing Ferraris would soon become iconic. With the rise of commercial television in the 1980s, the dedicated Italian audiences no longer swarmed to the cinemas as they had done in the past. Movie production declined and by the late 1990s, 80% of Cinecittà was sold off privately. A fire in 2007 destroyed around 3000 square meters, another in 2012 destroyed the Teatro 5, the huge studio where Fellini filmed La Dolce Vita. Hollywood-made films began to dominate those theatres that survived.

Cinecittà lives on today, albeit on a somewhat more modest scale on the outskirts of the city, supplying the insatiable demand by international TV and film productions for ancient Roman backdrops, Rennaissance Villas and buzzing, scooter-infested piazzas for suave café society sets. Since the 1990s it’s been the production hub for noteworthy films such as Anthony Minghella’s The English Patient (1996), Scorcese’s Gangs of New York (2002), Wes Anderson’s The Life Acquatic with Steve Zissou and Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ in 2004. In 2019 The Two Popes utilized the studios’ reconstructed Sistine Chapel. Various TV series were filmed at Cinecittà too: BBC/HBO’s Rome (2004 – 2007), an episode of Doctor Who in 2008 and Paolo Sorrentino’s The Young Pope and The New Pope. An alternative universe opened its doors to the public in 2014. Guided tours of the permanent sets will be possible on Saturdays and Sundays only.